With the sight of that final third star in the sky, signifying the end of the Jewish Sabbath, Sen. Joe Lieberman, D-Conn., finally made his way to the University of South Carolina campus Saturday night for the first debate of all Democratic presidential candidates. And even top aides from opposing campaigns acknowledged that he shined more than the others, emerging as the event's twinkling star.

"If he'd done that in 2000 we wouldn't even be here tonight!" a non-Lieberman staffer snarled at a Lieberman spokesman after the debate, referring not just to the disappointing conclusion of the 2000 election but to Lieberman's oft-derided performance opposite Dick Cheney in their one debate face-off.

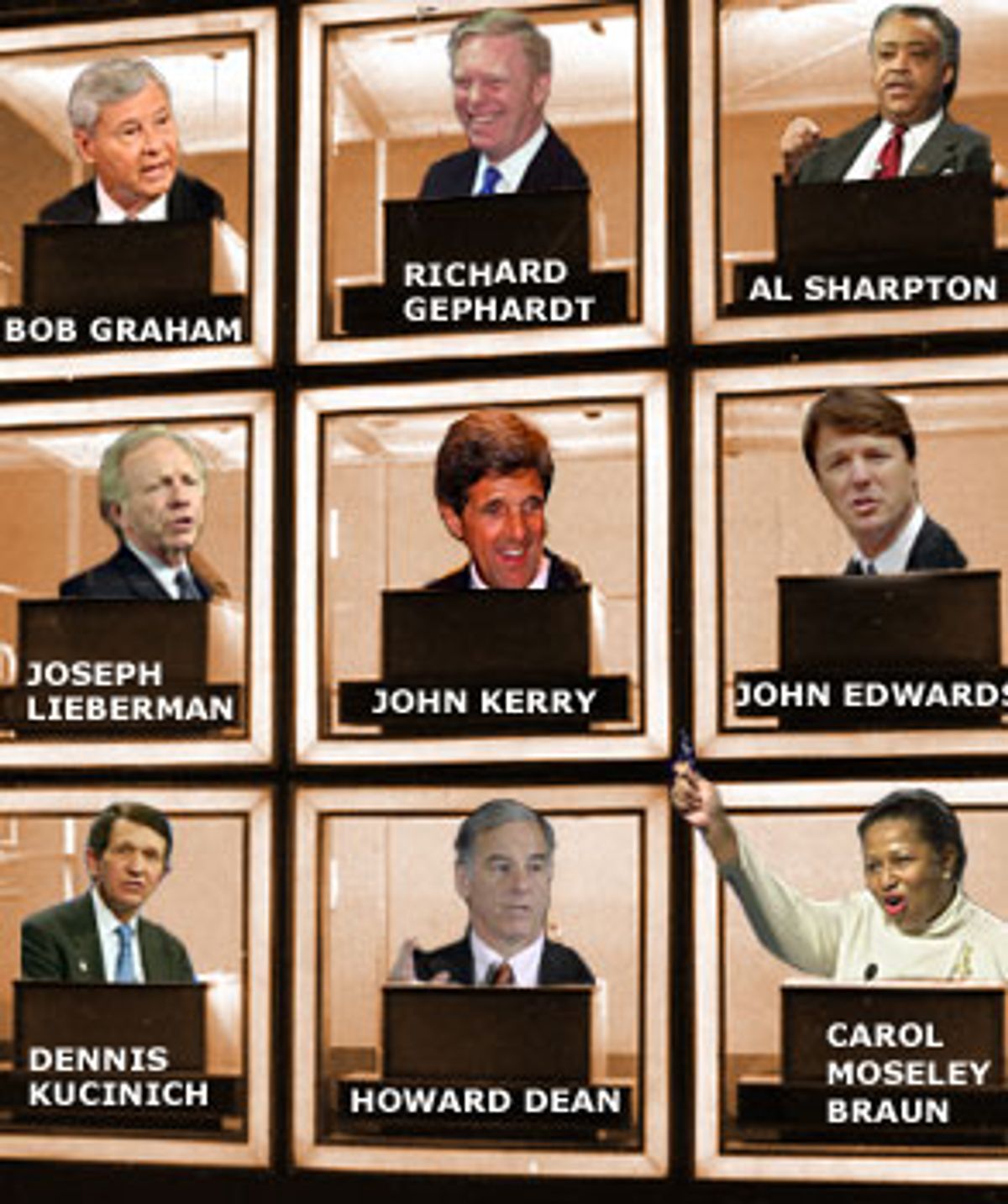

With a crowded field of nine sparring with each other, no one could really emerge as a clear victor. But Lieberman -- who caused the debate to be pushed back to a 9 p.m. start, after the sun had set and he had completed his weekly Sabbath observance -- strongly argued that he was the "one Democrat who can match George Bush in the areas where many think he's strong -- defense and moral values, and beat him where he's weak," on the economy and other domestic items -- and while doing so seemed to slightly rise above his peers, at least this night.

Much of this was also due to subpar performances by his rivals, most notably possible front-runner Sen. John Kerry of Massachusetts, who got bogged down in a petty snipe session with former Vermont Gov. Howard Dean over remarks each had made about the other in recent days, on Dean's healthcare record as governor, and Kerry's record on gay and lesbian rights.

Dean has yet to show himself as a threat on the national level, but he is competitive with Kerry in New Hampshire, which will hold its crucial first-in-the-nation primary on Jan. 27, 2004. He also appears talented at getting under Kerry's skin.

The South Carolina Democratic Party, not a traditionally strong organization in an overwhelmingly Republican state, secured a key spot for its presidential primary next year, on Feb. 3, 2004, one week after the New Hampshire primary and approximately two weeks after the Jan. 19 Iowa caucus. The debate was broadcast on ABC affiliates throughout the country after the 11 p.m. news, and will be rebroadcast on C-SPAN on Sunday.

It was thought that tertiary placement of the Palmetto State primary would help Sen. John Edwards of North Carolina, one of only two Southerners in the primary race (as he was eager to point out throughout the night), and the only one born here, before moving across the state line. But according to an American Research Group poll from the end of April, Lieberman -- the most conservative of the pack -- leads among likely South Carolina Democratic primary voters with 19 percent, followed by Rep. Dick Gephardt of Missouri with 9 percent, Kerry with 8 percent, and Edwards with 7 percent.

Recently, arguing in favor of improved diplomacy for the U.S., Dean said, "We won't always have the strongest military." With Dean a threat in a state Kerry needs to win, Kerry campaign spokesman Chris Lehane jumped on the statement, saying it "raises serious questions" about Dean's fitness to be commander in chief and that "no serious candidate for the presidency has ever before suggested that he would compromise or tolerate an erosion of America's military supremacy." Lehane and Dean campaign manager Joe Trippi slammed each other for a bit, after which Dean said, "I don't generally respond to campaign [operatives]," and said that Kerry "doesn't have the courage" to make the accusation to his face, prompting all sorts of outrage from the Kerry campaign, which cited its candidate's Vietnam War heroism and metals.

So Saturday night, ABC's George Stephanopoulos, the debate host, asked Kerry if Dean was fit to be president, and Kerry made it pretty clear what he thought.

The governor, Kerry said, "made a statement which I found quite extraordinary, and I still do ... I believe that anybody who thinks that they have to prepare for the day that we're not the strongest is preparing for a day when we have serious problems."

Stephanopoulos then asked Dean if he still thought Kerry lacked the courage to say it to his face. Kerry leaned forward to listen. "Everyone respects Senator Kerry's extraordinary, heroic Vietnam record, and I do as well," said Dean, who was constantly shuffling and reading various 3x5 cards. "This is 30 years later. I would have preferred, if Senator Kerry had some concerns about my fitness to serve, that he speak to me directly about that rather than through his spokesman."

There was a bit more crosstalk between the two. But ultimately it all enabled Lieberman to step up to the plate and criticize both men. "The squabble between Howard Dean and John Kerry may make interesting political theater, but it doesn't send the right message to the voters about our party," Lieberman said while Kerry winced. Voters, Lieberman asserted, are "not going to choose anyone who sends the message that is other than strength on defense and homeland security. The Bible says that 'If the sound of the trumpet be uncertain, who will follow into battle?'" The squabbling and their stances both send "an uncertain message," both Dean's opposition to the war and Kerry's "ambivalence," which "will not give the people confidence about our party's willingness to make the tough decisions to protect their security in a world after September 11."

Noted the Rev. Al Sharpton, a harsh critic of the war, "The same Bible, Senator Lieberman, said there's a time and place for everything -- a time for war, and a time for peace." Kerry disputed being ambivalent, and noted that "I'm the only person running for this job who's actually fought in a war."

Edwards' night was most notable perhaps for starting off with tough yet polite barbs against Gephardt's health insurance proposal. Indeed, that healthcare proposal -- once widely credited with giving the lagging Gephardt campaign some well-needed oomph, and with helping him to shore up some of the lefty Iowans he'd seemingly been losing to Dean -- suddenly seemed problematic. Edwards charged that the plan "takes money directly out of the pockets of working people and gives it to corporations," which to Edwards, a self-modeled John Grisham hero, would be bad, since corporations are evil. "It's like saying, 'You're in good hands with Enron,'" he said as he battled an audio problem, and a techie crawled on the stage to fix it. It would be, Edwards said, "trust[ing] corporate America to do what's right."

Lieberman joined in, saying it was an example of "backward" thinking, one of the unaffordable "big spending Democratic ideas of the past." Dean, who days ago referred to it as unrealistic and "pie in the sky," chuckled that the plan was "not as bad as John Edwards thinks, I was kind of shocked by that. It does not take money out of [the pockets of] working people." Kerry echoed the praise almost everyone offered to Gephardt in bringing up the subject at all, but then said that he "tend[s] to agree with my friend John Edwards."

Gephardt asserted that his opponents were misreading his plan, that the money wasn't merely going to corporations willy-nilly but so said businesses could provide healthcare services; he also stated that his plan was an attempt to not just mimic Republican policies. "If we're going to win this election we cannot be Bush Lite," he said.

As evidenced by both Lieberman's and Gephardt's comments, much of the conversation revolved around electability. Playing off Dean's claim to be "from the Democratic wing of the Democratic Party," Sen. Bob Graham of Florida said he came from "the electable wing of the Democratic Party."

At one point, Stephanopoulos raised the chief perceived weaknesses of each candidate. Kerry, accused of being aloof and lacking the common touch, joked that perhaps he "ought to just disappear and contemplate that by myself." Lieberman made a similar joke; when asked if he was too nice and not tough enough to be president, he said, "I'd like to come over there and strangle you, George!"

Each candidate was given two seats in the auditorium for staffers, though all were urged not to applaud lest time be wasted. The staffers for Rep. Dennis Kucinich of Ohio kept applauding so much an official had to come over and shush them.

When the candidates were afforded the opportunity to question one another, many took the Q&A as a way to preen further. See if you can figure out the real reason why the following questions were posed: Lieberman asked Carol Moseley Braun, the former Illinois senator, how they could ensure no more African-American disenfranchisement like that which kept him from the vice president's office. Edwards -- noting that he and Graham were both Southerners -- asked, "What do you believe we as Southerners can do to lift up and embrace people who" suffer from racial discrimination. Dean -- noting that he and Graham were both former governors with executive experience -- asked Graham why he voted for a bill in the Senate that he supports (and Kerry, Edwards and Lieberman opposed) that would have eliminated all of Bush's proposed $750 billion tax cut.

At the break between segments, while three makeup people rushed out to powder the punims of all nine candidates, Graham turned to Kerry. "I got all the questions!" he smiled, Kerry patting him on the back.

Shares