From the time Ken Starr captured Monica Lewinsky in January 1998, through the submission of his report to the House Judiciary Committee in the fall, he maneuvered toward a show trial of President Clinton the likes of which had not been seen since the impeachment and trial of President Andrew Johnson in 1868. The complex legal maneuvers over abstract concepts like executive privilege were but skirmishes that preceded a monumental battle over very large political questions: about the Constitution, about cultural mores and the position of women in American society, and about the character of the American people. It was, ultimately, a struggle about the identity of the country. President Clinton understood that; his wife did, too; so did many people in the White House; and so did Ken Starr and the Republican leaders. It was why he and they were fighting. So the independent counsel drove his investigation relentlessly into open alliance with the Republican Congress. To stage an impeachment and trial, they required each other. Starr would produce the inevitable charges, the Congress the inevitable judgment.

Over the next months, Starr's storm enveloped in shadow and fog everyone standing in his path. He and his supporters needed a convenient explanation for their continued failures and Clinton's popularity. As they saw it, Starr should be acclaimed a national hero, and the president already should have quickly resigned. But the drama wasn't unfolding as they had imagined it should. Eventually, in their angry frustration, they would wind up blaming the American people.

In the meantime, I became a target that could personify their political troubles. Almost anything bad that befell Starr or the Republicans they would blame on me, whether they believed it or not. I would be their scapegoat. I inflicted political damage on Starr when I lashed out at his inquisition following my appearance before his grand jury in February. Thereafter Starr and his deputies tried to restore his image by trashing me. Sticking pins in me was intended to harm the president. I also became a screen on which Starr projected his own underhanded techniques: just as he had invaded the president's sex life, I would be accused falsely of invading his opponents'.

Starr had allies among reporters, editors, and pundits who had aligned themselves with his cause, and these now assailed me, a former journalist who had crossed over to being an object of their scorn. Others followed their lead in a tail-holding line of conventional wisdom, parading as bravely independent. As for the people in the conservative movement who had reviled me ever since I had started reporting on them for the Washington Post in the Reagan period, I was the class enemy, "the devil," as they put it (for example, in a front-page headline in the New York Post). In the literally thousands of attacks that were made on my character, not one mentioned a policy or even a political issue. "I don't know much about him but he's just a scummy guy," a prominent Republican operative, Ed Gillespie, was quoted as saying in the Washington Post. (A former aide to House Majority Leader Dick Armey, Gillespie was the chief lobbyist for Enron.) Whenever it turned out that I wasn't who they said I was, the attacks only became nastier.

The stereotype conjured up of me was a series of contradictions: an omnipotent yet weak person, repulsive yet seductive, in a superior position achieved by unethical means. For example, Michael Kelly, in a column in the Washington Post, called me "Sid the Human Ferret" -- a subhuman. Not a single documented incident was cited to verify this portrait of a vile, unspeakable presidential aide, except the obvious fact that I supported the vile, unspeakable president.

On the morning of my first grand-jury appearance I had had to walk through shouting reporters and snapping cameramen just to get to my car. I did not resent them for doing their work, but I had to put on a game face to go down the sidewalk in front of my own house. All of us who worked at the White House had to gird ourselves every day. Whatever I was feeling had to be tamped down. Anger, frustration, suspicion, doubt, had to be suppressed. Sometimes when the accusations were particularly outrageous I felt compelled to respond, but usually I did not.

Self-control didn't arrive on the doorstep like the daily newspaper. I had to put on a suit of armor every morning -- and keep it fastened all day long. While the blows rained down there was little to do but weather them. Inexpressiveness became the psychological order of each day, exhaustion the constant physical condition. Once, I found myself asleep standing up at a public event in the East Room. I came to think of this as a political version of trench warfare as in the First World War -- occasional ferocious battles, a mile gained or lost, and no end in sight.

Perhaps the most helpful advice I received was from Hillary. "Remember," she told me, "it's never about you. Whatever you think, it's never about you." It was about President Clinton, about his agenda, about the Constitution. At a certain point, even the president had to think it was not about him. This insight enabled you to surmount the distractions of personal attack and maintain a clear sense of what was important. The more personal the attack, the more you had to grasp that it was political.

I had decided when I joined Clinton's White House that it was worthwhile to endure the criticism that came my way. I made another decision after January 21, when I decided to fight to preserve Clinton's presidency for all that it still promised for the country. I made yet another decision after being subpoenaed by Starr. I decided not to back down when I became a lightning rod. At each point, there was no way to assess what the personal toll would be on me or my wife and sons, who became touched, too, by anger and frustration at the assaults on my integrity. But there was a toll. Jackie responded at first by writing letters to newspaper editors and reporters she knew to protest stories that trashed me, but then she gave up; it was like spitting into the wind during a hurricane. There was no way to set things straight or expect that a rational explanation would be accepted in the midst of this storm. If people thought I was opaque and icy, or a mindless follower, or self-aggrandizing, so be it. I had decided that what I felt was not that significant. Confidence that we would prevail was the best and only face to wear. Loyalty was the only sentiment to display. Self-denial was the price of public service that had to be paid.

While Starr's prosecutors were composing his report to the House Judiciary Committee, they came to him to express their doubts about including salacious sexual material, which they considered irrelevant to the legal case. But Starr insisted that every detail be jammed in. "We need to have an encyclopedia," he said. "I love the narrative!" Lewinsky's lawyers, Plato Cacheris and Jacob Stein, had not set parameters on her testimony when they delivered their client to Starr with her proffer, and from the media accounts, they learned that Starr intended to include unedited transcripts of the phone conversations she had had with Linda Tripp, which contained unfiltered sexual talk and denigrating references to the Lewinsky family. On September 9, the lawyers met with Starr to tell him of their objections to the possible inclusion of this material. But he explained it was necessary. "We don't want to leave stuff out because it will look like we are concealing or not giving them all of the facts," he said. The Washington Post's Bob Woodward described Starr saying this as he "folded his hands and rubbed them together." Starr added, "I don't think we can remove all of the F-words." In its detail and tone, Starr was truly the author of the Starr Report.

Almost immediately after his conference with Cacheris and Stein, the previously notified television networks broadcast pictures of two vans loaded with boxes of the report and supporting material being driven slowly to the House of Representatives. Two days later, without any member having read it, the House made the report public, posting its 452 pages instantly on the Internet.

The Starr Report is among the strangest sex books ever written. Its two main characters are an infatuated, needy young woman and a middle-aged man who tries time and again to end the affair but allows his instinct to override his sense. The story is ordinary, squalid, and unhappy. What distinguishes this dreary tale from countless others of its kind is the unusual narrator. He is omniscient, hovering even in the bathroom. He sees everything, recording every sexual gesture bloodlessly. Every sexual encounter is footnoted. He is cloaked as an antiseptic clinician -- pornography in a white laboratory coat. The graphic detail is relentless, the prose as antierotic as possible. The characters are described as complementary in their mutual debasement: the woman is depicted as guilty and innocent, bad and wronged; the man is innocent and guilty, susceptible and wronging. But the narrator's obsession extends beyond his two protagonists. He introduces another character who is always on his mind, but whose absence is his only reference: "Mrs. Clinton was in Africa. . . . Mrs. Clinton was in Ireland." The author's intent to humiliate focuses on her, too. He wishes her to be stained as well. There is no other reason for her inclusion. The inference is that what offends the narrator was not so much the affair as the marriage.

The White House was hushed while staff members read the report on their computer monitors. In the East Room that morning, the president attended a long-scheduled National Prayer Breakfast, telling more than one hundred religious leaders, "I don't think there is a fancy way to say that I have sinned. It is important to me that everybody who has been hurt know that the sorrow I feel is genuine... Legal language must not obscure the fact that I have done wrong."

Later that day -- September 11 -- President Clinton addressed the memorial service at the National Cathedral for the 12 Americans killed in the terrorist attacks on the U.S. embassies. (In Kenya, 213 people were killed; in Tanzania, 11 were murdered, and about 5,000 were wounded.) Pledging that he would not "rest as terrorists plot to take innocent lives," he said, "For our larger struggle for hope over hatred and unity over division is a just one... We owe to those who have given their lives in the service of America and its ideal to continue that struggle most of all." In the media, busy with the tumultuous response to the Starr Report's release, the struggle against terrorism was a mere footnote if it was mentioned at all.

The weeks surrounding the release of the Starr Report were like one continuous day for me, for the Republicans were ratcheting up my evil profile. The degeneration of politics into personal demonization reflected the growing frenzy of the effort to overthrow the president. On Sunday, September 6, the unveiling of the Starr Report had been prepared for by two conservative panelists on ABC's "This Week." George Will stated, "We have the experience recently of a member of the White House staff, Sidney Blumenthal, calling journalists in an attempt to smear Henry Hyde." Bill Kristol jumped in: "It is a fact that Sidney Blumenthal has called members of the press to try to get them to look into congressmen's private lives."

Though I was unsurprised at being used as a scapegoat, I still registered alarm at hearing false allegations about me on national television. The charge was, of course, completely false. It was not, as Kristol blithely said, "a fact," and neither he nor Will would or could offer any facts. In the curious ambit of Washington, these ideologues with their counterfactual slurs were accorded respect, deference, and, most important, time on television. In their punitive ad hominem style, their insults substituted for facts. They indulged in character assassination while parading as the ones exposing it.

A correspondent at ABC News told me that Dorrance Smith, executive producer of "This Week" and communications director in the previous Bush administration, was pushing the line against me hard. My lawyer wrote the ABC News Washington bureau chief a sharp letter: "Mr. Blumenthal has never -- never -- attempted to smear Representative Hyde in any way... Neither Mr. Will nor Mr. Kristol presented any facts in support of their false and defamatory allegations, and neither cited any sources for their remarks. Neither Mr. Will, Mr. Kristol, nor anyone else from ABC News spoke with Mr. Blumenthal or anyone at the White House about these accusations before you aired them, or so much as attempted to do so. Your broadcast disregarded the truth. While no one harbors any doubt that both Mr. Will and Mr. Kristol reflect a partisan line, that your show would present their false propaganda as 'news' reflects poorly on your standards and practices."

It was apparent from this preemptive strike at ABC that there must be a story floating out there about Hyde. That week a number of journalists had bantered casually about Hyde and sex, as though the subject were a commonplace one. One, Jeffrey Toobin, my former colleague at the New Yorker, raised the subject with me. I recalled that my mother, who had been in secretarial pools in Chicago in the 1940s, had told me that she and others avoided Hyde's office because of his reputation, but that was all I knew about the subject.

Henry Hyde was the chairman of the House Judiciary Committee and therefore would preside over an impeachment hearing. The fiction broadcast by Will and Kristol had a patently political intent. Claiming that the White House was smearing him could not have had a more jagged partisan edge. I asked White House legal counsel Chuck Ruff his advice, and he suggested that I write a private letter to Hyde. I wrote, "I was appalled to hear George Will on ABC's 'This Week' this past Sunday suggest my name in connection with raising personal questions about you. I simply want you to know that I have not and would not do that, and that there is no truth to it." I had the letter hand-delivered to his office by a White House courier. I did not make it public; nor did Hyde.

On the eve of the Starr Report's being thrown onto the Internet, the president's chief of staff Erskine Bowles summoned me to his office to hear a report from Larry Stein, the White House legislative liaison. Stein said that Newt Gingrich's aide was claiming that I was spreading sexual stories about the Speaker of the House. Bowles asked if that were true, and I replied that it was not. And I resented the question. Gingrich, in fact, would later leave his second wife for a woman with whom he had been having an affair for years and whom he had placed on the House payroll. Many journalists had long heard rumors about this dalliance, and Gail Sheehy, in an article in Vanity Fair in 1995, had mentioned the name of his "frequent breakfast companion," Calista Bisek. Clearly, Gingrich was worried about being exposed. His office had been a center for sexual smearing for a long time, since in 1989 it had put out the false rumors that then Speaker Thomas Foley was gay. Perhaps Gingrich made the projective assumption that everyone operated the way he did, but I wasn't engaged in sexual outing. Nor did I know of anyone in the White House doing it. Frankly, given the incendiary political environment, if any of us had chosen to float that rumor it would undoubtedly have been published instantly. Quite on their own, the Republicans had created a political free-fire zone in which their hypocrisy now invited exposure.

Indiana's own Mr. Conservative, the inquisitor of the House, Dan Burton, who had called the president "a scumbag," was the first to have his hypocrisy revealed. His hometown newspaper, the Indianapolis Star (owned by the family of Dan Quayle), reported that he had an illegitimate child. Burton defended his private life, even the principle of privacy, while trying to cast aspersions on Clinton's. "I have never perjured myself," he protested. "I have never committed obstruction of justice. I have been as straight as an arrow in my public duty. But this is private."

Then Idaho's advocate of right-wing militias, Representative Helen Chenoweth, the one who had promoted theories about a United Nations invasion with black helicopters, ran a television commercial against her Democratic opponent in the upcoming election: "Bill Clinton's behavior has severely rocked this nation and damaged the office of the president. I believe that personal conduct and integrity does matter." Her hometown newspaper, the Idaho Statesman, took that as license to expose her affair with her married former business partner.

Some Republicans nimbly defended this hypocrisy as simply the double standard of traditional values and therefore another mark against Clinton. Bill Kristol was quoted: "I'm not at all convinced it helps Clinton to have the Burton and Chenoweth stories come out. Republicans have old-fashioned extramarital affairs with other adults. Those really are moral lapses that are private and more easily forgiven and very different from taking advantage of a young person who works for you when you're president."

The Starr Report had unleashed animosities that hardly anyone anticipated would now rip into the drama.

Over the past seven and a half months, a retiree in Florida, Norman Sommer, had sent out 57 letters and made dozens of phone calls to news organizations prodding them to write a story about his friend Fred Snodgrass. Snodgrass had been a furniture salesman in Chicago whose marriage was broken up in 1967 when his wife, Cherie, had an affair with a 41-year-old lawyer and aspiring politician named Henry Hyde. Snodgrass was still bitter, and Sommer was acting as his agent.

On September 16, Salon published Snodgrass's account. Cherie, through a daughter, also acknowledged it. Hyde issued a statement assigning it to his "youthful indiscretions." Snodgrass was quoted: "And all I can think of is here is this man, this hypocrite who broke up my family. . . . I hate the man. He destroyed my kids, me. I'm not a vengeful person. And I don't have anything against Cherie anymore. Of course, it takes two to tango and maybe I wasn't the best of husbands. But he got away with it. He doesn't deserve all this ovation, this respect."

The editor of Salon, David Talbot, published an accompanying article explaining why he was publishing the piece. "The White House had nothing whatsoever to do with any aspect of this story," he wrote. "We did not receive it from anyone in the White House or in Clinton's political or legal camps, nor did we communicate with them about it. Norman Sommer, the man who did lead us to the story, categorically denied to us that he had any connection to the Clinton administration." Then he offered as Salon's justification for releasing this information the following argument: "If the public has a right to know, in excruciating detail, about Clinton's sexual life, then surely it has an equal right to know about the private life of the man who called the family 'the surest basis of civil order, the strongest foundation for free enterprise, the safest home of freedom' -- and who on Monday indicated that he believes impeachment hearings are warranted."

When the article was posted on the Internet, I was in my office working on a Third Way conference, "Strengthening Democracy in the Global Economy," that was going to be held in less than a week at the New York University School of Law. As I was making last preparations, Bowles sent a message that he wanted to see me.

Erskine asked me if I was responsible for the Salon piece on Hyde. I told him categorically that I was not. John Podesta was in Erskine's office as well, reading through the article. "It says here," he said, "'The White House had nothing whatsoever to do with any aspect of this story.'" Blaming me was nothing new, an aspect of the campaign against the president. The lawyers, inside and outside the White House, understood that well but warned that it was a shaky political moment.

The days after the Starr Report's release produced the greatest fear inside the White House since the first week of the scandal. A new NBC News/Wall Street Journal poll showed that 60 percent of the American people believed the president had obstructed justice. Some congressional Democrats were unsteady. Senator Joseph Lieberman had given a speech denouncing Clinton's behavior as "immoral" and went up to the edge of calling on him to quit. Most of us on the White House political and legal staffs believed that Starr had written his salacious report to shame Clinton into resigning. No one knew what would come next. Gingrich called Clinton a "misogynist" and was demanding that the networks broadcast his videotaped deposition. The video might be even more damaging than the Starr Report -- a coup de grbce. In living color, in everyone's living room, a whole nation might be repelled. The Hyde incident provided the Republican leadership an opening for calculated attack, allowing them to provoke the media into delirium and to push the White House, stoked with concentrated fear, into a defensive crouch.

Mike McCurry, the press secretary, issued a statement: "We were in no way connected to the Salon story." That evening, all three networks broadcast bulletins about Henry Hyde, with ABC reporting in an early broadcast that two anonymous sources claimed that I had peddled it to them. In a later version I became an unnamed White House official.

The next day, Bowles sent a letter reassuring Hyde that the White House had had nothing to do with these reports, that it "is informing news organizations that it waives any right to journalistic confidentiality about the sources of such stories," and that "any staff who are found to be engaging in such conduct will be fired." This was a Kafkaesque position, fending off a false charge but attempting to show good faith by expressing willingness to punish the nonexistent offender.

At a press conference, Speaker Newt Gingrich's whip Tom DeLay released a letter calling for an FBI investigation signed by the Republican House Leaders -- Gingrich, Majority Leader Dick Armey, Deputy Whip John Boehner, and himself: "Whether or not that specific story originated with the White House or its allies, clearly there is credible evidence that an organized campaign of slander and intimidation may exist. If these reports are true, the actions of the individuals responsible are pure and simple intimidation -- no different than threatening jurors to change their verdicts in organized crime trials." No evidence was offered, no examples cited.

When asked what proof he had that the White House was behind the Hyde story, DeLay blurted out, "No, I don't have any evidence." Then he said darkly, "We have reason to believe that top aides that have access to the Oval Office have been orchestrating a conspiracy to intimidate members of Congress by using their past lives." As he went on, he grew more certain: "A number of published reports have pointed to Mr. Blumenthal as at the heart of the White House strategy. We know why these stories happened. We know others are coming." He finished with a flourish: "If we find out who is responsible, this could be added to the impeachment inquiry."

Throughout the day, I watched this spectacle unfold and decided I had to speak in my own voice, and within that news cycle. I told Erskine, who thought it was a good idea, and conferred with Ruff, who was supportive. Then I issued a statement: "I was not the source of, or in any way involved with, this story on Henry Hyde. I did not urge or encourage any reporter to investigate the private life of any member of Congress. Any suggestions otherwise are completely false." But my disavowal did not quell the fury. Nor did the accurate report on CBS News that night by Bob Schieffer: "Several Washington reporters told us a Florida man named Norman Sommer" was responsible for the story and that "Sommer says he was operating on his own, not at the request of the White House."

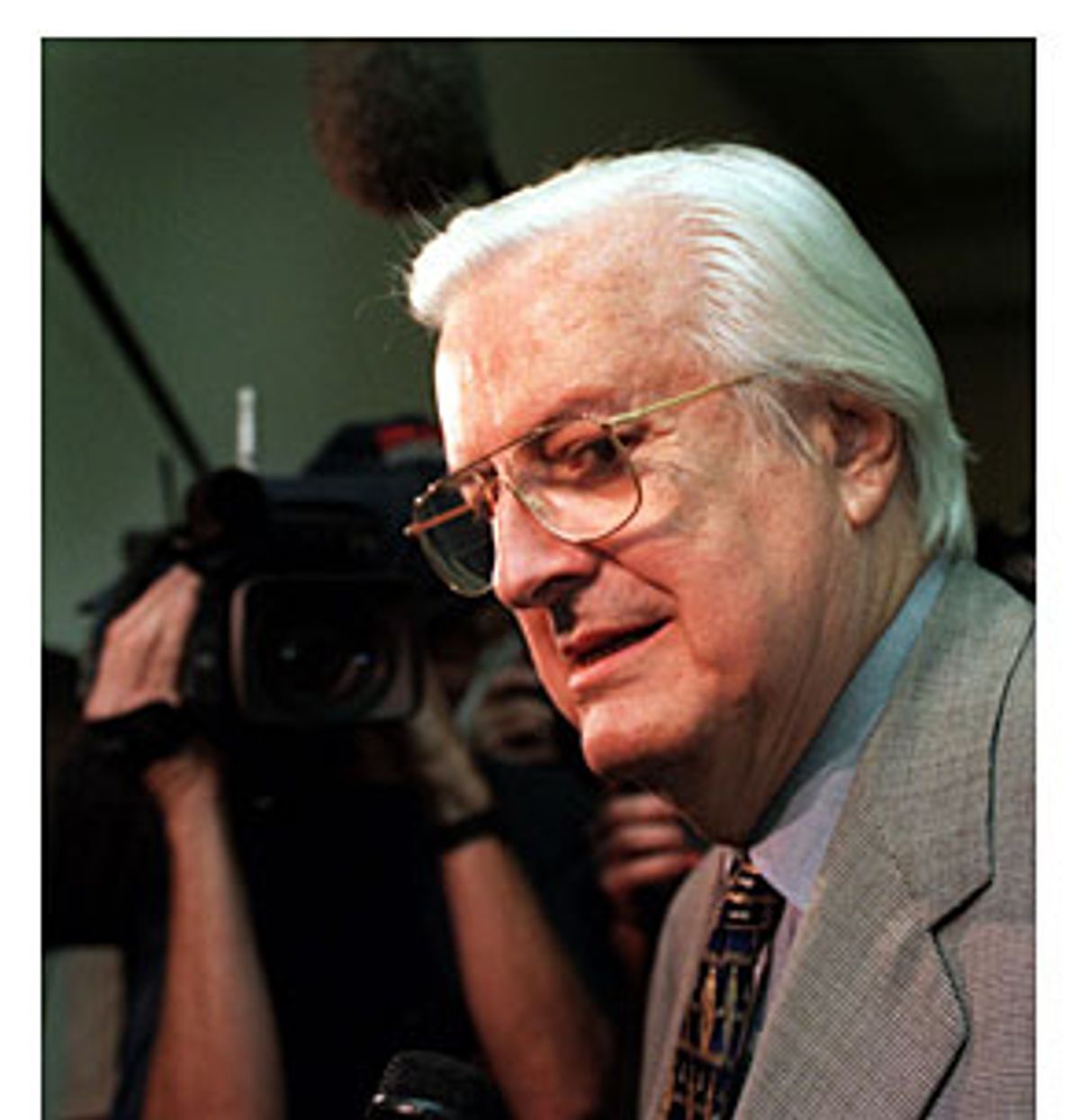

The following day, September 18, the New York Post ran my photo on its front page next to a huge headline: "BILL'S DIRT DEVIL." Above that ran another headline: "GOP Suspects Clinton Henchman Is Top White House Smear-Meister." Inside, there were more headlines -- "White House Eyed in GOP Sex Smears" and "Controversial Aide at Center of the Storm" -- with the lead story, which read, "Furious Republicans yesterday called on FBI chief Louis Freeh to probe whether the Clinton White House is running a slime machine to fight Sexgate by slandering its enemies." It ended, "Republicans wondered aloud who would be next -- perhaps Gingrich?"

In the Washington Post, Representative Ray LaHood, an Illinois congressman close to Hyde, continued the finger-pointing: "I think this is Sidney Blumenthal's M.O. Blumenthal is a sneak. He's out to destroy people's careers, and he ought to be fired." Asked for proof, LaHood replied, "Process of elimination." Joe Lockhart, the White House deputy press secretary, suggested that LaHood "should forward to us any credible information he has. If he has no such information, he should keep his thoughts to himself. Otherwise he's engaging in rumor, innuendo, and anonymous gossip."

The efforts to demonize me got so outlandish that I jokingly greeted my White House colleagues with the Rolling Stones' lyric from "Sympathy for the Devil": "Please allow me to introduce myself..." And after a briefing of the president in the Oval Office that I and a number of others attended, Clinton asked me to stay behind. Once we were alone, he said, "Listen, I know all this stuff about you and Hyde is total bullshit. Don't let it bother you." "Thanks," I said. Within the White House, the Kafkalike trial was over.

Excerpted from "The Clinton Wars," by Sidney Blumenthal, to be published on May 20 by Farrar, Straus and Giroux LLC. Copyright 2003 by Sidney Blumenthal. All rights reserved.

Shares