Media accounts describe him as phony and calculating, incapable of making a heartfelt statement. His history is analyzed cynically, sometimes falsely: Misrepresentations of his statements and actions metastasize into myth. As a result, he is seen as the archetypal slippery, soulless politician. That much of the supporting evidence is false seems utterly beside the point.

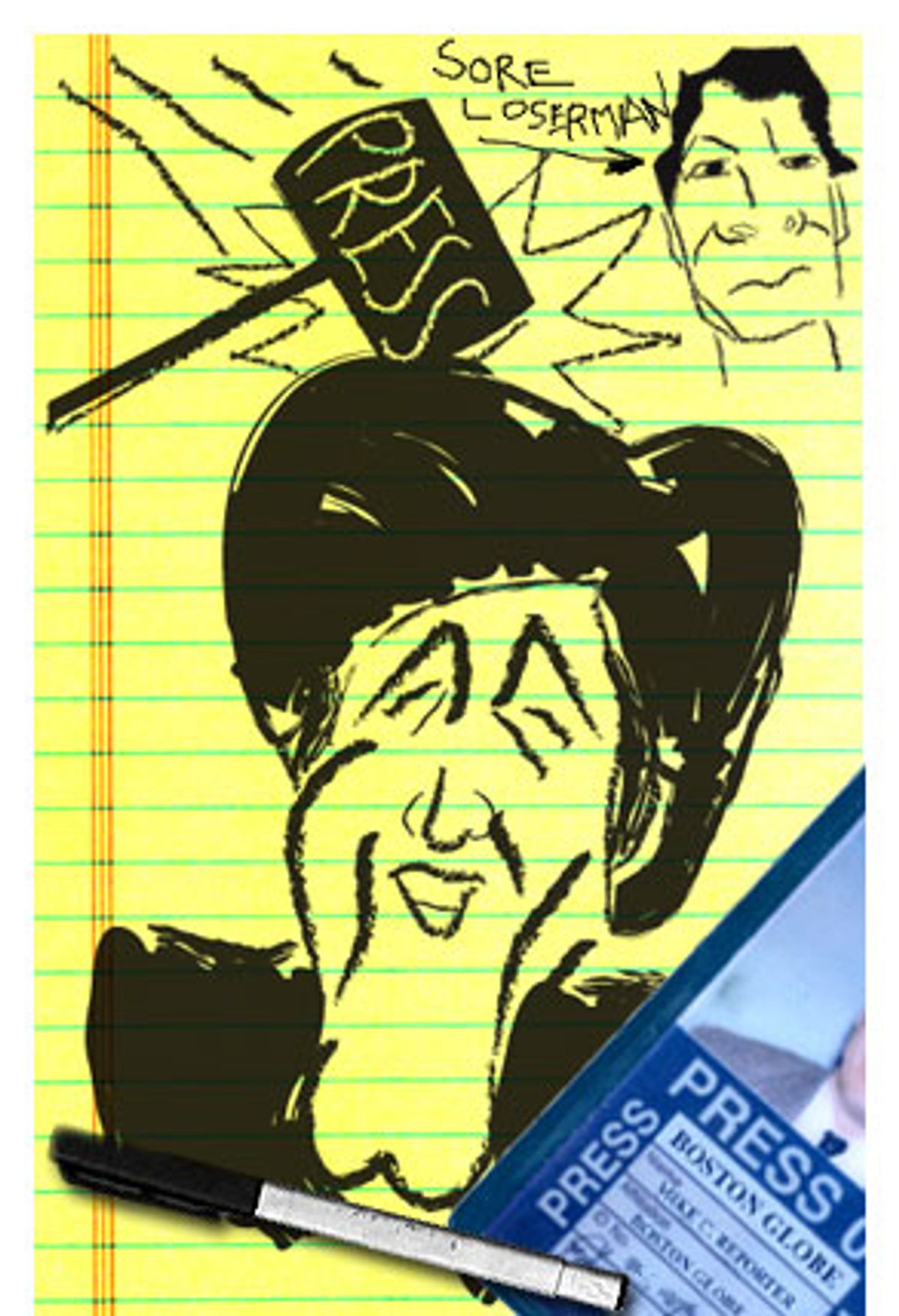

That's how Republicans caricatured Al Gore in 2000 -- a line the media dutifully parroted. And as the 2004 presidential campaign gets underway, it's happening again. This time the victim is Sen. John Kerry.

Like Gore, the Massachusetts Democrat has been characterized, with some justice, as being aloof and cold. On Saturday, when asked about his haughty image during the first debate among the Democratic candidates, he tried to laugh it off (in much the same way Gore unsuccessfully joked about being stiff in 2000) by suggesting he "ought to just disappear and contemplate that by myself."

But the press has pushed its pseudo-analysis of Kerry far beyond the innocuous observation that he lacks charisma. And in so doing, it is following the same irresponsible course it did with Gore.

As Gore and now Kerry are learning the hard way, you can't laugh off an image problem to a press corps that now almost always takes personality more seriously than policy. That reporting style has exploded in popularity ever since the New York Times' Maureen Dowd took her acid observations on the presidential campaign trail in 1992 and became a household name. The Washington Monthly observed at the time that "Today's campaign planes and buses are freighted with Dowd disciples: hyperliterate capital-W Writers with an eye for detail and an ear for the shuffling going on behind the curtain." Over time, it's created an even greater blood lust among political reporters for that canny observation or cutting insight -- and whether they are true or not doesn't always seem to matter.

Take Kerry's recent statement at a New Hampshire town meeting that "we need a regime change in the United States." In many ways, the quip illustrated much that might be seen as objectionable about Kerry. The slogan, after all, has been used to describe the U.S. effort to remove Saddam Hussein from power and implies that the regime in question is illegitimate, perhaps even fundamentally evil. Was this an inflammatory and crudely partisan effort to stir up the Demos' Bush-hating base? You could make a pretty good argument that it was.

But the Weekly Standard's Noemie Emery saw much, much more. Rather than just criticizing the implicit comparison of Bush to Saddam, she wrote that Kerry's "turn of phrase can be put down to pandering, over-exuberance, or the wish to appear as too fiendishly clever"; described the "outburst" as motivated by polls showing Kerry tied with Howard Dean in New Hampshire; and announced that "Kerry is now brilliantly situated to make a run for President of France." In one article, Emery demonstrated three of the key tropes built into the media's coverage of Gore and turned them against Kerry: the assumed phoniness of everything he says, the assumed cold political calculation behind every move he makes, and the belief that individual gaffes demonstrate deep, fundamental character flaws.

It would be tempting to attribute these patterns to Emery's basic ideological disagreements with Kerry if her tactics weren't so eerily parallel with those of the press covering Gore three years ago. The absurd lengths the press went to in its coverage of Gore has been well documented (by no one more than Gore friend and partisan Bob Somerby, and also by Salon and others), and showed that, as the American Prospect's Paul Waldman wrote, "In 2000, reporters hated Gore's guts. They bristled at his inaccessibility, they derided his campaign's strategy and, most of all, they thought he was a phony." Mainstream, conservative and even some liberal journalists frequently portrayed Gore as an inveterate liar, harping on myths such as the false charge that Gore claimed he invented the Internet or that he inflated his journalistic experience by two years on his résumé.

No matter how untrue these claims were, they proved irresistible to the press, and were used by outlets such as the Boston Globe to justify conclusions like: "Gore has regularly promoted himself, and skewered his opponents, with misleading and occasionally false statements," according to a story by Walter Robinson and Michael Crowley. Gore was also often portrayed as a cold and calculating political robot -- at one point, CNN political analyst William Schneider suggested Gore might have "planned" to make himself perspire at a town hall meeting in New Hampshire in order to "make himself look like a fighter."

This is not to say, of course, that Gore and Kerry have not engaged in their share of exaggerations and political calculation over the years. Kerry has been legitimately criticized, for instance, for taking unclear and seemingly contradictory positions on issues such as the Iraq war and affirmative action. He has also benefited from misconceptions in the media that he threw away his own medals during a Vietnam War protest, and that he is Irish. But these individual examples don't come even close to justifying the dominant narrative that treats the candidate as a lying phony -- nor the contortions journalists have used to support it.

In Gore's case, the creation of the image of a phony opportunist took years of work, work that originated primarily in the world of conservative pundits and the Republican National Committee press operation. Indeed, Somerby has demonstrated that several of the most prevalent myths about Gore -- such as the claim that he said he invented the Internet, and that he grew up in a fancy hotel -- originated in RNC press releases. Conservatives were so successful in framing coverage of Gore's persona during his later years as vice president that their version was in place in time for the 2000 campaign. In Kerry's case, right-wing pundits such as Emerie have already had an impact on mainstream press coverage. But the Gore-ing of Kerry has been helped along significantly by the hostile coverage of his hometown newspaper, the Boston Globe.

It was the Globe, in fact, that signaled this past February that press coverage of Kerry was going to follow the Gore pattern. That's when the paper ran a front-page Sunday story with a new revelation about Kerry's roots. After an exhaustive investigation conducted by a genealogist hired by the Globe, it revealed that Kerry's paternal grandfather was Jewish, a fact the senator never knew. The article did not specify exactly why this investigation was valuable to the public, but hinted at the rationale when it noted that some media outlets have incorrectly reported that Kerry, who shares a name with a county in Ireland, is Irish -- an influential credential in Kerry's home state, where Kennedy nostalgia still holds a certain sway.

A month later, the Globe went on the offensive with the revelation that, in 1986, Kerry entered a statement into the Congressional Record that began, "For those of us fortunate enough to share an Irish ancestry ..." However, the fourth paragraph of the Globe's article makes it clear that the statement was written by a Kerry aide and the senator never actually saw it, let alone read it aloud. Nonetheless, the Globe made this nonrevelation front-page news, stating, "Some observers have suggested a lack of clarity about his family origins reflects Kerry's ill-defined identity and tendency to leave misimpressions that are politically advantageous to him." That observation mirrored an earlier comment by Globe columnist Joan Vennochi, who wrote, "Kerry's confusion about his heritage mirrors a larger confusion about his essence: Who is he? What does he believe in?" Just as Gore was constantly accused of "reinventing" himself, Kerry supposedly lacked a core "essence" because he didn't know his grandfather was Jewish.

It's also notable that while the Globe seemed to blame Kerry for this identity confusion, the only evidence that Kerry ever claimed he was Irish was the Congressional Record statement, a draft of remarks prepared for him in 1984, and a 1993 interview with the conservative pundit John McLaughlin in which, when asked if his father had any Irish ancestry, Kerry replied, "I don't know the answer to that." Indeed, that Globe article at least pointed out that Kerry's spokeswoman said the senator "has corrected any misstatements he became aware of," and that the Globe itself had made the false assumption that Kerry was Irish three times over the years (a figure the Globe later upped to eight).

A few days later, the Globe took Kerry to task in another article for not publicly discussing his family background before its investigation -- although it's not at all clear why voters need to know the intricate details of a candidate's family background. "Never in his 21-year career in public life has Kerry gone out of his way to explain his complex roots," Globe reporter Anne Kornblut wrote, "even though he discovered some 15 years ago that his paternal grandmother was Jewish, a point he has mentioned only occasionally in public." The implication is clear: Because Kerry did not preemptively reveal personal information of questionable relevance, he had been deceptive.

The Globe, of course, is not alone in these sorts of attacks. Radio host Rush Limbaugh made it clear what he was trying to do when he recently said on his Web site that "Senator John Kerry has a bad case of the Algores." The alleged lie in this case was that Kerry told a group of parents and children who live in a polluted area in Massachusetts that "Until I went to Washington, I had never had asthma in my life," blaming pollution there for the condition. He later clarified that he infrequently uses an inhaler to treat springtime allergies. To most people, it may be obvious that Kerry's clarification simply explained the extent of his asthma. To Limbaugh, the asthma flap deserved the "did he or didn't he inhale?" treatment. "Kerry did what the press calls 'clarified his remarks,'" Limbaugh told his listeners. "That's what the press calls it when a Democrat admits he lied."

Another myth that has made the rounds about Kerry is that, while serving in Vietnam, he filmed himself in an attempt to exploit his military service for future political use. New York Times columnist Bill Keller repeated this lie last August, when he wrote that "with all due respect for [Kerry's Vietnam] exploit, how utterly weird is it that he then took out his handy 8-millimeter camera and re-enacted his heroism on film?" A month later, Keller apologized to his readers, admitting, "The first thing to be said is that the senator's movies are not self-aggrandizing. Kerry is hardly in the film, and never strikes so much as a heroic pose."

Keller's source for this mistake? None other than the "usually dependable Boston Globe," which, as Bob Somerby has pointed out, wrote in a 1996 profile of the senator: "The young man so unconscious of risk in the heat of battle, yet so focused on his future ambitions that he would reenact the moment for film. It is as if he had cast himself in the sequel to the experience of his hero, John F. Kennedy, on the PT-109."

Like much of the media dissembling that circulated about Gore in 2000, such as that he claimed to have discovered the pollution at Love Canal, it is disturbing not only that these myths circulate throughout the press, but, worse yet, that such falsehoods are used to reinforce the existing narrative of the candidate as a politically calculating liar.

These alleged lies touch on another favorite tactic in the Gore/Kerry story line: giving great weight to flimsy personal information. Gore, for instance, was frequently mocked for trying to appear more "authentic" when he began wearing more casual clothes on the stump. Kerry, meanwhile, has already, improbably, taken heat for the cost of his haircuts.

But it's worse than that. A story last June by Michael Crowley in the New Republic, headlined "Can John Kerry Make People Like Him?" was full of enough psychobabble to make the coverage of Gore's personal life seem hard-nosed. Crowley lets his readers know that Kerry "evinces a distinctly self-indulgent streak." The evidence? "Kerry speeds around on a motorcycle and a convertible. Rollerblades and wind surfs, and he plays classical pieces and Broadway show tunes on his guitar." Crowley writes, "[I]f the broad contours of Kerry's biography suggest vanity and opportunism, it's easy to find details that support that impression." Such as? Apparently, "during his famous anti-war testimony before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee in 1971, Kerry seemed to affect a Kennedy-esque accent," and "early in his career he had surgery on his chin -- a medical procedure, he said: gossip columns called it a cosmetic adjustment." Kerry-led investigations into the fate of POW-MIAs in Vietnam and the BCCI banking scandals were "showy," to Crowley. He then concludes by recounting a brief conversation he observed Kerry having with a black female conductor of a Capitol Building subway car. Some might see this as nothing more than a politician's penchant for being genial, but Crowley felt that Kerry "saw this cultural chasm as an opportunity to practice his charm skills."

To fully enter the woolly world of irrational Kerry rage, though, one has to read Slate blogger Mickey Kaus, who jokes that the Globe's piece on the senator's Jewish grandfather was really a plot hatched by Kerry -- "a convenient bit of de-aloofifying drama" -- and has run a "Kerry Mystery Contest" that asks, "Why is it that so many people, myself included, intensely dislike Sen. John Kerry?" Kaus' own clever reason: "the phony furrowed brow." Every aspiring Beltway smartass surely clucked along in appreciation.

Like all politicians, Kerry engages in his share of contradiction, truth stretching and opportunism. He should be nailed for it. But the creation of Kerry the Phony is a lazy conceit by journalists more interested in taking easy shots than raising real questions. It's much easier to find dark significance in rollerblading, chin surgery and conversations with subway conductors.

And the campaign shows no signs of abating. According to a report in the Capitol Hill newspaper the Hill, the Globe is currently working on a new investigation of the 1980s dating habits of Kerry, who separated from his first wife in 1982 and didn't remarry until 1995. Here's a wild guess: Whatever information the intrepid reporters find, it may very well illustrate some fundamental character flaws in the senator. Quite possibly, it will show that Kerry is "aloof," "self-indulgent," or maybe even a "phony."

Shares