The stories that the veteran soul performers gathered in the documentary "Only the Strong Survive" have to tell include, for some, doing lots of drugs and being cheated out of royalties by record companies. For all of them, the implicit story is about retaining your profile in a business where heritage matters for almost nothing and memory seems to stretch back no further than last week's Billboard Hot 100. On top of all this, did they have to suffer directors Chris Hegedus and D.A. Pennebaker's lousy filmmaking?

"Only the Strong Survive" is a shoddy, borderline incompetent documentary that offers next to no context, a movie in which the performers are lucky if the filmmakers show them performing one song all the way through. The look of the movie -- shot by five cameramen, including the directors -- is washed out and drab. Shots often begin out of focus and the close-ups are so haphazard that parts of the performers' faces are sometimes cut off. As a tribute to the men and women gathered herein, the movie is an insult. As an example of cinéma-vérité technique, it's a bad joke.

When I use that term, I'm basically referring to a documentary film that records what happens, without the use of interviews or voiceover narration. It's not a form of moviemaking that can be unconditionally recommended. Too often, the directors' insistence that removing themselves from the process allows events to proceed without their influence is essentially false. It denies the part the filmmakers play in shaping the events we see (as in the Maysles brothers' "Gimme Shelter"), and denies the audience vital information by refusing to put what we see in context. That's not true in the films of Frederick Wiseman, whose documentaries provide an example of how cinéma-vérité can produce eloquence and empathy for the people who appear on camera.

The biggest shock of "Only the Strong Survive" arrives in a clip of Otis Redding performing in an earlier Pennebaker movie, 1967's "Monterey Pop." In terms of technique and expressiveness, "Only the Strong Survive" is a de-evolution for Pennebaker. It's not just that many of these performers have been doing these numbers for years or, in the case of the Chi-Lites, are doing them at polite, suburban venues (places like the Westbury Music Fair on Long Island), that makes the performances here so much less vibrant than the ones Pennebaker captured in "Monterey Pop" or in his film with Bob Dylan, "Dont Look Back." More than that, it's the haphazard method of filming, the constant nagging suspicion that the filmmakers are going to cut away from the performers.

After "The Last Waltz" and "Stop Making Sense" and "Buena Vista Social Club," even after less accomplished concert films like Prince's "Sign 'o' the Times," how does anyone have the nerve to try and get away with this? It would be as if someone had made a straight-faced movie, right after "Star Wars," in which a flying saucer is a pie tin hanging by a string. One of the film's producers, Roger Friedman, a cheery, portly soul music fan, appears throughout the movie, telling the performers about some great performance he saw them give or other undistinguished fan gush. I guess putting up the money has its privileges. When Sam Moore, half of the great duo Sam and Dave (the other half being the late Dave Prater), and his wife go to the New York offices of Atlantic Records, Mrs. Moore suggests that the filmmakers come in to film the company accountant when they ask about the royalties Sam is owed. Moore laughingly demurs.

But it's a damn good idea. If you're going to tell the story of what happened to these people, if you're going to make them worthy of that horrendously overworked appellation "survivor," doesn't that require a filmmaker to get to the bottom of things, to ferret out the people controlling the purse strings and offer some hard evidence about what the company has made on them versus what they've actually been paid? But that kind of direct inquiry would be an intrusion of muckraking technique into cinéma-vérité, though it would also give the audience some of the context that this movie cries out for. How about investigating what these men and women are earning in the age of sampling, when vintage soul hits appear over and over again in movies and TV ads? That subject would also give us some idea of the depth of these performers' influence.

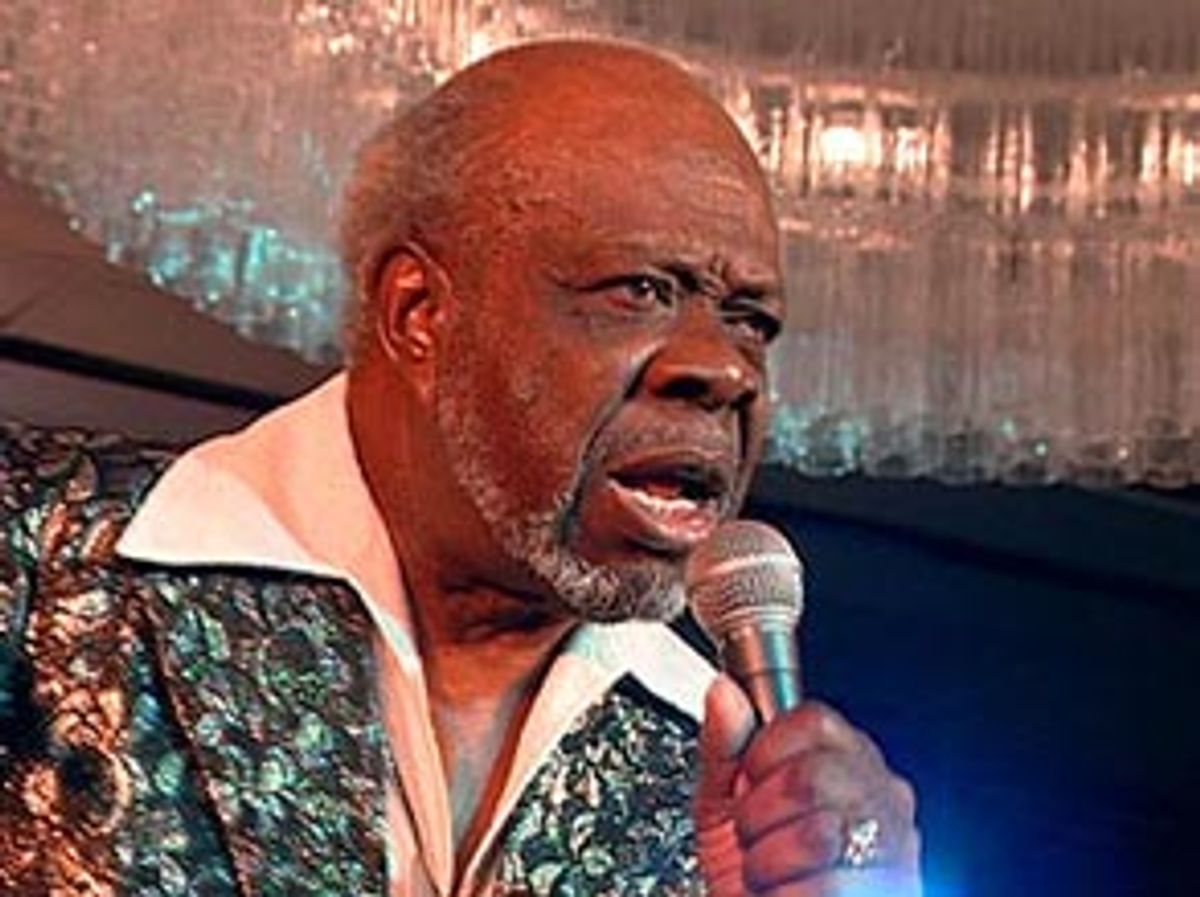

Issues arise and then disappear again. We learn that Jerry Butler, the singer whose milky baritone was first heard on records by the Impressions, went into Chicago politics and was elected Cook County commissioner. But we never find out how he made the transition. When the late Memphis performer Rufus Thomas, a great growling clown of a performer, introduces the older white woman who for years was his seamstress and tells us that she has been taking care of him daily since a heart operation, you'd like the filmmakers to interview her and to hear more about their friendship. Don't Hegedus and Pennebaker know that everybody in the audience who loves soul music is thinking "God bless her," and wants to find out more?

Instead, the audience is reduced to the status of hungry pigeons begging for crumbs. Such crumbs come in scattered moments, like the wonderfully indiscreet Wilson Pickett recounting how ugly he found Diana Ross as a teenager, and later doing a really raunchy bump and grind with a large woman he pulls from the audience. (I wished we'd heard Pickett doing the '80s number whose title sums up the aggressive raunch of his approach: "Lay Me Like You Hate Me.") It's great to see Sam Moore throwing his all into a performance at an Isaac Hayes tribute, or to register the proud beauty of former Supreme Mary Wilson or to hear that Carla Thomas, Rufus' daughter, still has that baby-high singing voice.

I loved Hayes' admission that he took to wearing dark glasses because he was shy, and that he was terrified to appear on "American Bandstand." You get about one minute, though, of Hayes performing -- what else? -- the "Theme From 'Shaft.'" I'd love to see him and his band stretching out on those wildly overproduced and overlong orchestral arrangements he did of songs like "Walk on By" and "By the Time I Get to Phoenix." And there's no story here to match the one the writer Robert Gordon tells in his wonderful 1995 book "It Came From Memphis," about Don Nix and Duck Dunn of the Mar-Keys, who were at the Stax studios in Memphis the day Martin Luther King Jr. was shot in that city. "Duck Dunn and I started to go out to our cars," Nix remembered. "Isaac Hayes came and said, 'No, I'll drive you out,' because it was doubtful we would have made it." In that moment, the shy Hayes was Shaft.

But all "Only the Strong Survive" has to offer are scraps, and it's a sad thing to sit through a movie billed as a tribute to a group of terrific performers and to come away with nothing more than scraps. None of them are lessened by their association with this slipshod movie. The shame is on the filmmakers for the tattiness of what they've produced -- for not paying back an ounce of the joy they say this music has given them.

Shares