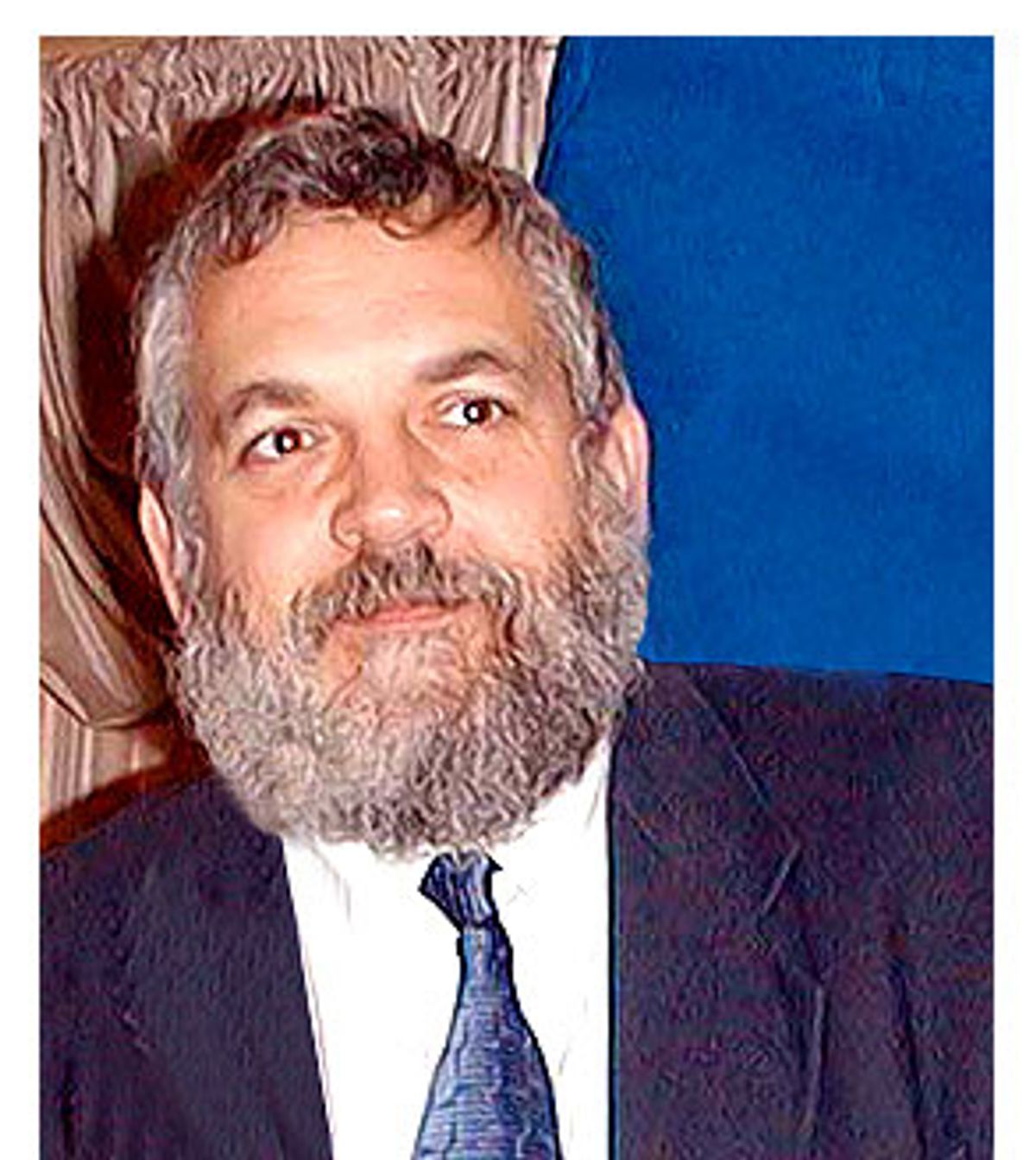

Benny Elon, Israel's minister of tourism, has a handshake as soft as butter. He is built like Santa. His voice is so gentle that you need to lean forward to catch everything he says. It is tough to reconcile the man with his reputation as one of the least tractable and most radically right of Israel's political leaders. He travels with two armed bodyguards and starts visibly at loud noises. His caution is understandable: Elon, who is also a rabbi, assumed leadership of Israel's Moledet Party in 2001 after the previous leader, Moledet founder Rechavam Zeevi, was assassinated. He and his party are committed to an Israel that stretches from the Mediterranean to the Jordan River, an outcome that Elon believes is both promised by God and made inevitable by realpolitik. It hinges, however, on a radical and polarizing notion -- that Palestinians can and should be "transferred" out of Israel.

"The Palestinian Arabs already have a state," says Elon. "It's Jordan. Another state west of the Jordan River is a three-state solution, not a two-state solution. It would be a disaster for Israel, and it would be a disaster for the Palestinians."

Last week, only days after the Bush administration's road map for peace in the Middle East was released -- which calls for a Palestinian state in what most of the world considers the "occupied territories," but which Elon, the Israeli right-wing and significant elements of the U.S. Congress considers part of biblical "Eretz Israel" -- Elon traveled to Washington to present a plan of his own. It is simple: Give Palestinians a state by granting them Jordanian citizenship. Solve the Palestinian problem by declaring there will be no separate Palestinian state at all. Make the West Bank and Gaza a part of Israel -- or rather, acknowledge what Elon already considers to be fact. The plan requires the "transfer" of Palestinians from Israel to Jordan, which Elon insists would be voluntary. But those who refused to transfer, under Elon's plan, would be considered foreign nationals and denied Israeli citizenship.

Elon's party and his opinions are more extreme than the Likud, the party of Prime Minister Ariel Sharon. Elon also believes that Muslims should not be able to vote in Israel, not even those who are currently citizens. And he has predicted that Islam will be wiped out in a few years by a Christian crusade. While these ideas are considered extreme in Israel, many in Sharon's coalition government share Elon's hard-line policy against dismantling any of the Jewish settlements in the West Bank and Gaza; Sharon himself has publicly advocated the "Jordan is Palestine" viewpoint, most recently in Haaretz, an Israel paper, in April 2001. And while Sharon criticized Elon's lobbying trip to Washington, it's clear from the objections he raised with Secretary of State Colin Powell that the Israeli prime minister, too, has significant problems with the road map.

Regardless of whether his trip was sanctioned by Sharon, Elon found sympathetic listeners in the United States, both on Capitol Hill, where he met tirelessly with U.S. senators and representatives of both parties, including Lindsey Graham, R-S.C., and House Majority Leader Tom DeLay, and in the evangelical Christian community, where he has gained the support of lobbying groups such as the Christian Coalition and Gary Bauer's American Values. While the official purpose of Elon's visit last week was to promote Israeli tourism, he also found time to discuss his comparatively radical solution to the Palestinian question.

"I had to check for myself how congressional leaders feel about the road map," he says. "I was like someone going to comfort, who finds himself comforted by the words of the other. It's not my task to raise their objection to the road map, because they already have it. I hope we can find together a more creative and more peaceful alternative."

The reasons for Capitol Hill's affection for Israel are complicated. Israel's well-funded lobby certainly plays a role, as does the lack of any pro-Arab constituency in the United States. Religion also plays a role: Prominent Christian legislators, including DeLay and Graham, have spoken out regularly and vociferously in support of Israel, especially since the Palestinian intifada began two years ago. Support for Israel has increased since Sept. 11. President Bush, who has argued that the United States must fight terror everywhere, finds some members of Congress openly criticizing him for what they see as a contradictory stance when it comes to the Palestinians.

I asked to accompany Elon and his advisors to some of his meetings on Capitol Hill last week. Elon agreed. What follows is a view into the careful influence-building that goes on every day on Capitol Hill, in this case, on a topic of great concern for the world. Lobbyists of every political persuasion are busy promoting their interests regarding the road map, of course. Elon's message, though, has the advantage of being very simple to understand, and for that reason alone it appeals to those who understand the world as an "If you're not with us, you're with the terrorists" kind of place.

It's early afternoon on May 6. Elon is already running late for his meeting with Lindsey Graham, the Republican senator from South Carolina. We are racing through the corridors of the Hart Senate Office Building, the tourism minister in front, like the prow of a ship, pushing people out of our wake. Behind him trail his chief of staff, Chaim Silberstein; the Israeli ambassador for tourism, Rami Levi; Elon's press person, Ronn Torossian; and Elon's armed bodyguard, who throughout the day remains unnamed and unsmiling. That morning Elon has already attended the Israel Solidarity and Prayer breakfast, where he told 800 Christian supporters that Israel would never give up the West Bank, and met with Dick Armey, former House Majority Leader, who has publicly supported the "transfer" of Palestinians to Jordan. There is a flurry of cellphone calls. An Israeli news crew outside the Senate Office Building wants to interview Elon. His trip is big news in Israel, especially after Sharon chastised him publicly for meddling with the peace process. The news crew is granted access. After finding a convenient American flag to stand next to, Elon is ready. The news correspondent gets right to the point. Silberstein, Elon's chief of staff, translates from the Hebrew for me.

"Is it true that you are here to sabotage Bush's efforts for peace?" the interviewer asks.

"No," says Elon. "I came to promote tourism issues. I am not here to undermine Bush or Sharon. Nonetheless, if certain issues come up, I won't hide my opinion. My opinions are well known, I think."

"Are you concerned that the Bush administration isn't meeting with you?"

"No. That's not my place. I prefer to have the message come to him through my Christian contacts here in the United States."

After a few more questions from the Israeli news reporter, it's on to meet Graham, who greets Elon like an old friend. Graham, a devout Christian, is a trim man with a quiet manner and a perpetual glow. In 1999 he received an honorary degree from the conservative Christian Bob Jones University. Last October he spoke at the Christian Coalition's "Solidarity with Israel" rally, an event held to express opposition to an independent Palestinian state. The two men take chairs half-facing each other, like visiting statesmen, which they are. The rest of us fan out in available chairs a respectful distance away. The bodyguard waits outside.

True to his word, Elon talks tourism, although there is very little difference, when it comes to Israel, between talking tourism and talking politics.

Elon invites Graham to come to Israel to tour the Temple Mount.

Graham's smile doesn't waver.

"Why, I remember that caused quite a stir when Sharon came to visit there," he says.

That's an understatement. Jews and Christians revere the Temple Mount, where King Solomon built a temple in 950 B.C. Muslims, who call it Haram as-Sharif, believe it is where Mohammed was carried up to heaven and consider it Islam's third-holiest place, after Mecca and Medina. All that reverence has made the Temple Mount a popular place for unspeakable violence between religious extremists. Today the plateau is the location of two mosques, Al-Aqsa and the Dome of the Rock. In what was widely seen as a provocative move, Sharon visited the Temple Mount on Sept. 28, 2000, accompanied by 1,000 police officers. Palestinians were outraged, and violence began that continues through today. In short, the Temple Mount is a flashpoint for all that has gone wrong with the Middle East peace process, and it is the most volatile place a U.S. senator could possibly travel in Israel -- especially at the invitation of the Moledet Party leader.

But Graham is game. "Let's plan on it," he says. "I don't think you'd invite me if you thought I was going to get hurt."

Polite laughter follows. Silberstein suggests the May 29, "Jerusalem Liberation" day, which in other circles is known as the day in 1967 when Israelis occupied East Jerusalem. An aide brings a calendar. The 29th is out. Graham is visibly disappointed but finds another date, and he promises to bring other senators with him when he comes. The meeting ends with handshakes all around. Elon is jubilant. He makes his way to the next meeting, led by a security guard. We follow.

Graham's office did not return calls asking for a clarification on his goals for visiting the Temple Mount. Silberstein offered this explanation of its significance, however: "The Muslim policy is that it's their site," he explained. "They think Jews and Christians are heretics. If a U.S. senator who is also a Christian breaks the taboo, then it's going to be difficult for [the Muslims] to flare up. The only question is how many senators will be willing to do this pilgrimage."

Elon next meets with Max Burns, a freshman representative from Georgia. Burns was an upset Republican winner in a new district gerrymandered to be predominantly Democratic. He still looks dazzled to find himself in Congress.

"I made an important commitment during my campaign to visit Israel during my first term," he tells Elon. "I'm fortunate enough to have been elected, and I'm not going to wait. It's important for me to get there, to see how the people live, to learn what they are like, to eat and shop with them."

Why is it important for Burns to get to Israel? The congressman is an active member of his Baptist church and has served as a deacon for 15 years. He raises Sept. 11, as well; it's clear he feels a deep affinity for the sufferings of Israel because of those terrible events.

The affinity that some Christians feel toward Israel is often explained in terms of eschatological prophesies -- that they believe after the Jews return to claim the Holy Land, Jesus will return and his believers will be taken into heaven. But to leave it at that trivializes the reverence felt for the Holy Land by many Christians, especially those who are intimately familiar with the Bible and who know that Jesus scolded the Apostles for asking him when the kingdom of Israel would come, telling them it was not for them to know. Evangelicals also know without looking it up that Jesus' last words to his Apostles, in Acts 1:8, were of Judea and Samaria --names still used today by Israelis for the geographical territory also known as the West Bank. The religious beliefs of the Jews speak to devout Christians in a language as familiar as a beloved psalm; indeed, they are identical. Kinship with Israel was all the more strengthened after Sept. 11, when they began to identify with Israel and against what they felt was a common enemy.

Elon has gained the most traction with those Christian leaders whose pronouncements are not only pro-Israel but also overtly anti-Muslim, such as Pat Robertson, who was rebuked last week by the National Association of Evangelicals for his inflammatory remarks about Islam, and Roberta Combs, who sponsored a symposium this spring titled "Muslims and the Judeo-Christian World: Where to From Here?" where not a single Muslim was invited to speak, and where the roster was dominated by topics like "Islam and Violent Trends" and "The Dangers of Islam's Spread to Christianity."

"[Christian fundamentalists] are people who are wild about Israel and believe in the annexation of Judea and Samaria and even the transfer of Palestinians from the soil of the land of Israel," Elon said to Israel's Haaretz Daily just before his visit to Washington, in a quote Elon's spokesperson says is accurate. "Compared to them, I am considered a dove." In meetings I watched Elon regularly speak of "our Christian friends in America" and need prompting by his handlers to mention American Jews. It's understandable: Jews in this country are a politically diverse constituency trending toward liberal and are only about 6 million strong; evangelical Christians are as many as 60 million strong and vote in a bloc on the far right of the political spectrum, making them, ironically, a far more potent ally of Israel than American Jews.

In addition to meetings with congressional leaders last week, Elon talked strategy with leaders of conservative Christian lobbying organizations, including Mike Evans of the Jerusalem Prayer Team, a group that has gathered more than 23,000 signatures for a letter to President Bush urging him to reject the road map, and American Values, led by former Republican presidential candidate Gary Bauer, who last March said: "We believe in the Abrahamic covenant. We believe God owns the land and he has deeded it to the Jewish people, a deed that cannot be canceled by Yasser Arafat and cannot be amended, even by the president. This God has spoken clearly. He said, 'He who blesses Israel, I will bless; he who curses Israel, I will curse.'"

But Burns is not a fire-and-brimstone evangelical by any means: He is simply a Christian believer. His campaign promise to visit the Holy Land speaks to a far broader sympathy for Israel beyond those Christians looking to hasten the end of days.

"Your country and your people have suffered greatly," he tells Elon. "I hope for the day when there is a stable peace in the region. It's going to take some changes. It's going to take the Arab world taking control of their extremists who would destroy any chance for peace."

Elon was also warmly met by some Democrats on Capitol Hill, notably Rep. Shelley Berkley, D-Nev. Berkley has been an active supporter of the Bush administration's Iraq policy, but is troubled by what she sees as a contradiction of his stance toward terrorism when it comes to the road map.

"Candidly, the discussion [with Elon] was more about my own unhappiness with the proposed road map rather than his," she says. "Last June, President Bush gave one of the best speeches he has ever made. He said that Arafat was no longer a viable partner for peace and would have to step down. He said there had to be an end to terrorism, and an end to the funding of terror cells, and an accounting of where all the money has gone that was given to the Palestinian Authority by the European Union and the United States, because it's certainly not going to the Palestinians who with every passing year sink deeper into an economic and spiritual depression. I'm concerned the president is putting pressure on Israel to dismantle the settlements when quite frankly none of these things have happened."

Elon is indefatigable. Today he is meeting with four freshman congressmen for the first time, along with senior members of Congress with whom he has long-standing relationships, and he treats each with equal deference. Torossian tells me he comes to the United States every two months or so, and always it's the same thing: a tireless round of meetings to explain his viewpoints. "We plant the seeds," he says. "Some sprout, some don't."

In the next meeting, his first with Rep. Steve King, R-Iowa, the seed blossoms. King first apologizes for his tiny office -- freshman representatives have a lottery to choose their quarters, and he evidently picked a short straw. We all squeeze in. He makes do with just one aide. An abundance of elephants decorate his desk, little ceramic GOP critters, and also a stack of three Bibles, which King makes reference to, though he does not explain why he needs so many. Silberstein brightens after he spies "Myths and Facts," a well-known pro-Israeli tome published by the American-Israeli Cooperative Enterprise, on King's bookshelf, and compliments him for owning it. The minister explains the tourism situation and asks for help in modifying the State Department's travel warning. But King wants to talk policy.

"I'm a Catholic," he says. His words have the weight of the confessional. There's that shimmering in the air that happens when two people are about to begin a deep conversation about things they believe in. "I was raised Methodist. Those are three Bibles on my desk. I have always believed the Jews were God's chosen people. I was born the year after you became a nation. I remember the 1967 war. You've stared in the face of evil like no nation ever has. As I watch the Arab world rise up, as I watch the murder of women and children, or any innocents, I have to say I don't know why you have the patience that you have."

There is a moment's silence, not at all awkward. "It's rare to hear something so clear," Elon finally says. "Yes, we are the children of Israel."

"I wonder why it was so simple in Afghanistan and Iraq but we need to negotiate with terrorists in your case, with the Palestinian entity," King says. "We can't come to something productive unless we adopt the same thing President Bush has taught the whole world is right."

"I can't ask the president to be more Catholic than the pope," says Elon, referring to his worry that Sharon might concede to the road map and give up settlements. (This was before Sharon laid out his problems with the road map with Secretary of State Powell.)

"I think the president understands," says King. "It was simple in Afghanistan, and simple in Iraq. We recognized them as terrorists. Meanwhile here are people as heartless and cruel as 9/11, and you're expected to negotiate with them."

King expresses his belief that the West Bank belongs to Israel, because Israel won the territory in the Six-Day War. According to international law, though, the matter isn't nearly so simple -- in fact, it's not possible to acquire territory through war. This is the basis of U.N. resolution 242, which insists Israel return the "territories" it captured in the war. All U.S. administrations have accepted 242 as the basis for Mideast peace; the current "road map" uses it as a cornerstone.

But Elon and King don't go over this history. Elon offers the congressman a glossy brochure that contains his complete peace plan, happy he has found a new ally.

Does Elon have enough clout to ensure that Israel blocks Bush's road map? His opinions are extreme at home. But the presence of his party and others on the right in Sharon's government has almost certainly slowed the pace of removing settlements in the West Bank, since any rash movement on Sharon's part could also take down his coalition.

Do Elon's opinions have enough support in the United States to influence the Bush administration? The evangelical Christian lobbies that agree with him most, including his claim that all of Palestine belongs to the Jews by biblical right, are some of Bush's most active allies. Sympathy for Israel runs deep enough for Elon to be considered a welcome ally even among those lawmakers who don't support transfer but who believe the road map forces Israel to negotiate with terrorists. This sympathy may help to explain Bush's muted enthusiasm for the road map: Just compare the fighter-jet grandeur of Bush's announcement of the end of the war in Iraq, with the road map release, announced in a written statement read by an underling on April 30.

"I'm worried about Elon's influence," says Lewis Roth, assistant executive director of Americans for Peace Now, the U.S. branch of Shalom Achshav, an Israeli peace organization that believes Israel's democratic and Jewish character are undermined by continued occupation of the West Bank and Gaza. "It's not Elon's first trip to meet with members of Congress. He has developed a constituency for what he has to say on Capitol Hill. He plays a role, and it's not a supportive one."

How could anyone think that the transfer of more than 3 million people from their home is a good idea? I ask Elon. He refers first to biblical prophesy. Then to recent history, including the Balfour Declaration of 1917, which declared that the British government looked with favor on the establishment of a Jewish national home in Palestine. After defeating the Ottoman Empire in World War I, Britain acquired control of historic Palestine, an area that roughly encompassed what is Jordan, Israel and the occupied territories today. Elon argues that the British government, and later the United Nations, drew a border that was arbitrary and could just as well have made the Jordan River the border between the Jewish and Arab states. (The Balfour Declaration also says that it is "clearly understood that nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities," a qualification that pretty much sums up the contradiction that is Israel.)

I then ask: Just what does "transfer" mean? The term brings to mind the troubling image of people being herded into railroad cars. But Elon insists that he is not talking about involuntary movement. Under his plan, those Palestinians who opt to stay in Israel would be granted the civil rights of resident foreign nationals, he says, with access to healthcare and education, as well as citizenship in Jordan, whose capital, he points out, is only an hour away from Jerusalem. He says he would give up the economic support Israel receives from the United States so that it could be used instead to aid these new Jordanians.

"Transfer must be entirely voluntary," he says. "We would raise money to support it. We would give up our assistance from America and give it to Jordan instead. Israel has to share her part in the solution."

"Voluntary" implies Jordan's cooperation with Elon's plan, but the foreign minister of Jordan calls the plan "ridiculous." Perhaps more important, "voluntary" implies that the Palestinian people will want to move. I can imagine them wanting to get away from the violence with which they live now. But wanting to move because your misery has grown too great to bear is not, strictly speaking, a voluntary decision.

"There's no such thing as voluntary transfer," says Roth. "You're dealing with a situation where Israel has enforced military occupation of the West Bank and Gaza and controls the lives of three and a half million Palestinians. There's an explicit policy of establishing a settler presence that breaks up the continuity of the Arab lands. Since the intifada it's been extremely difficult to have any sort of life there. Under these difficult circumstances, as the economy continues to take the stress, there is no such thing as voluntary transfer."

I next ask Elon how giving up all rights to citizenship in the West Bank and Gaza could make the Palestinians better off, an outcome Elon insists is the natural consequence of transfer. He shows me a map of the West Bank today, with Jewish settlements in red, Palestinian-controlled territories in white.

I have seen the map before, but this time I am starkly reminded of a map of South Africa during apartheid, when the ruling government carved out useless "homelands" for the Bantu peoples. Elon is right. It is difficult to imagine any sort of statehood in those fragments. Palestinians today are left with noncontiguous scraps of territories whose best areas have been chipped out of their control.

What if every settlement was rooted up, the West Bank and Gaza returned in their entirety? Elon says that a return to the borders prior to the 1967 war won't work, either. Those borders have never worked. There simply isn't enough room west of the Jordan for two viable states. "I want to show Arab Palestinians a new hope, not just have a cocktail party for diplomats that say shalom to one another," he says. "I'm saying, Let's solve this problem."

After speaking with Elon it seems hard to imagine that such a fragile political compromise as the road map will endure. And it occurs to me, after this day spent with fervent, self-proclaiming believers, that it's those who believe in the road map who have the real faith.

All day the tourism minister has been running late. He cancels a meeting with Christian radio personality Janet Parshall, much to her dismay. Other meetings fall by the wayside. Elon has simply run out of time. The morning before his plane leaves he packs in meetings with Gary Bauer of the American Values lobby and with Mike Evans, head of the Jerusalem Prayer Team, as well as with House Majority Leader Tom DeLay, meetings I was not permitted to attend. Then it's back to his hotel, where as always the room is entered and searched by his bodyguards before he goes in. A call comes in from Roberta Combs of the Christian Coalition; she reacts to the good news about Elon's meetings on Capitol Hill with joy so real that it is audible several feet away from the phone.

In a quiet moment, a visible weariness finally settles on Elon.

"After all we've accomplished, Israel is still just the biggest Jewish ghetto in the world," he says. "We're surrounded by people who still think of us as foreigners in our own country."

He does not add that his plan would do the same to the Palestinians.

This story has been corrected since it was originally published.

Shares