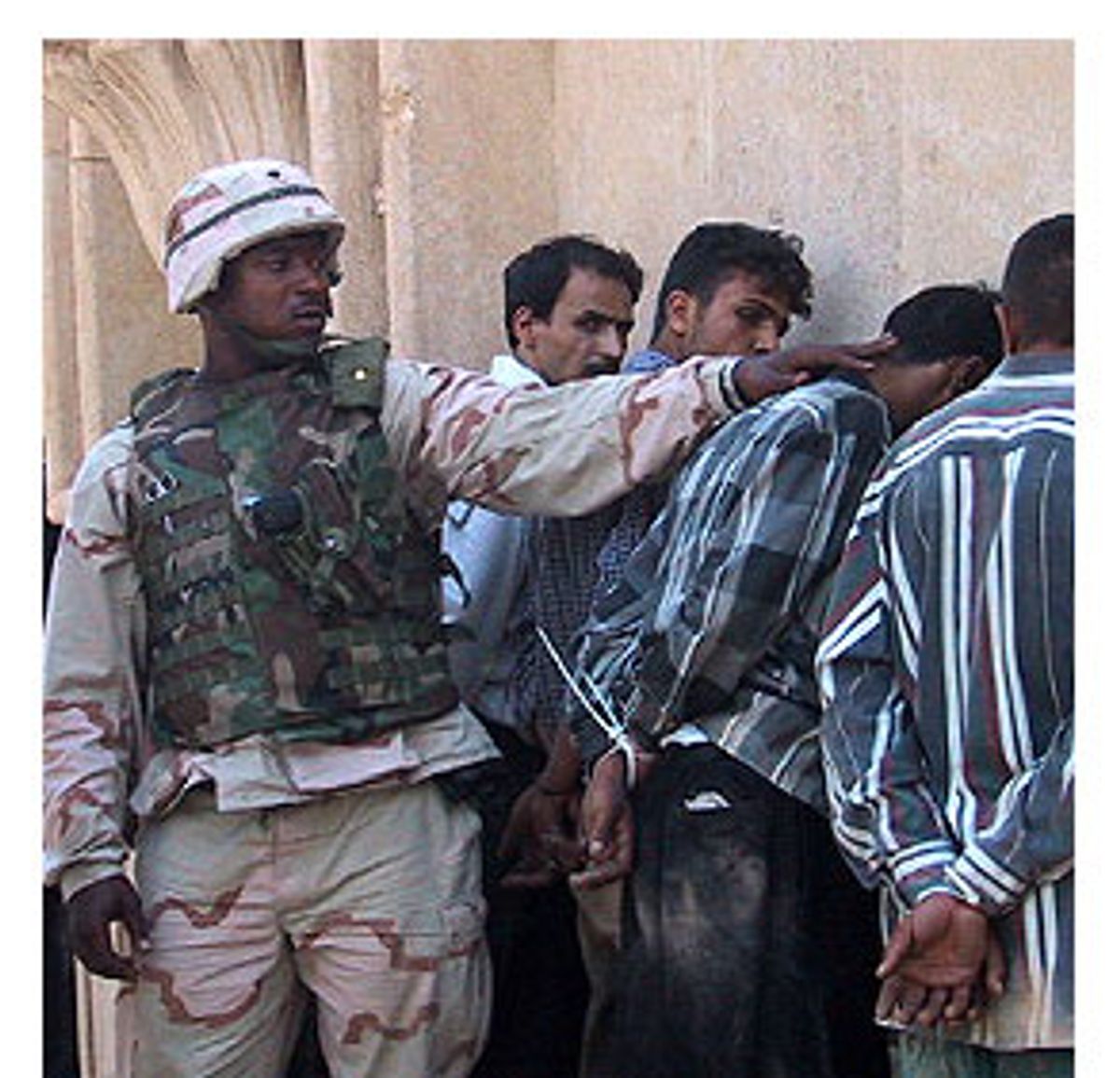

Three teenage brothers from Kerbala are sobbing near the entrance to U.S. Army headquarters in a former presidential palace. Their faces are pressed to a concrete wall, and their hands are bound with plastic handcuffs. The youngest, Fathyl Bander, is 13. He says they came to Baghdad to visit a cousin and they were having a look around the looted Iraqi TV building, not looting themselves. Whether or not that's true, they weren't carrying any stolen items when American soldiers from the 3rd Infantry Brigade put them under arrest.

A week ago, even if they had been clearly guilty, their crime probably wouldn't have been punished with more than a reprimand. But now the violence and anarchy that have convulsed Baghdad since the city fell threatens to negate whatever humanitarian achievements America can claim from the war, and this week marked the beginning of a campaign to turn the situation around. L. Paul Bremer, who took over the top U.S. administrative position from Jay Garner, is here to get tough.

U.S. Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld also announced this week that 15,000 new U.S. troops will be coming to Baghdad to help impose order. The New York Times reported Friday that they will supplement the efforts of 4,000 military police who are said to be en route to the Iraqi capital. And the former New York City police commissioner, Bernard Kerik, has signed on as a senior advisor in Iraq's Interior Ministry, the Times reported.

It remains to be seen whether the new personnel and the military's new, harsher rules of engagement will be an improvement on the laxity that's prevailed until now. But as the Bander brothers and hundreds of other suspected looters are finding out, the U.S. is sending an unambiguous new message in hopes of changing Baghdad's climate of insecurity.

At the moment, the joy many Iraqis felt at the end of Saddam Hussein's regime is being trumped by the terror on their streets. Carjackings are rife, Kalashnikovs and grenades are reportedly cheap and widely available, the hospitals are treating streams of gunshot victims, and there are numerous reports of women and girls being abducted and raped. The humanitarian agency CARE had two trucks stolen last week, and efforts to address the country's humanitarian crisis are being hampered by a lack of security.

"All Iraqi people believe all the crime in Baghdad belongs to the USA Army, because they did nothing to stop it," says Dr. Zakaria Al-Kazraji, a surgeon at the Baghdad Teaching Hospital who has treated dozens of gunshot victims since the war ended, many injured in fights between gangs of thieves. "The situation is deteriorating," he says. "Looters and thieves threaten doctors while they're treating them."

Al-Kazraji wanted the war, so desperate was he to see Saddam deposed, and he insists most Iraqis felt the same way. Nor has he changed his mind -- his country's current problems were caused not by bombings, he says, but by the failure of the occupying powers to restore order. That failure, he says, was exacerbated by Saddam's emptying of the prisons five months ago, freeing violent thugs along with political prisoners.

"War did not destroy our country," he says. "War destroyed the vital center of the previous regime. It's looters and thieves who have destroyed the Health Ministry and the College of Medicine. I don't hate Americans. America bombed us, but did America rob our hospital? No. Did America destroy our college? No. But when the ministry was destroyed by thieves, America didn't interfere. Why?"

If the United States can restore order to Baghdad, Al-Kazraji says he will support the occupation. Yet in a city as ravaged as this one, that will be a Herculean task. According to Amar Abd Al Hussen, an officer in the new Iraqi police force's department of information, there are only 200 Iraqi policemen currently on the job, and only a quarter of them are honest. "The gangsters of Saddam Hussein are still working here," he says. "They still have guns."

Sgt. Carlos Johnson of the 4-64 Armor Company says that when he tried to stop looting at the Ministry of Information, a thieving Iraqi policeman pulled a gun on him. Al Hussen says 10 or 15 girls have been kidnapped and "a thousand" cars have been stolen. "The Americans cannot stop it," he says.

Yet many troops from the 3rd Infantry have been told they can't go home until they do, and they're now working hard to enforce the military's new zero-tolerance policy on looters. Though some reports this week indicated the United States was considering a shoot-to-kill order for looters, that dramatic step has not been taken. Clearly, however, the U.S. has decided to send a new message after a month in which the policy had often seemed to border on official indifference. Until today, the few looters who were arrested were locked up for 48 hours and then released, while more serious criminals were put away for three weeks. Now, looters and suspected looters will be imprisoned at the Olympic Stadium for three weeks, and other criminals, presumably, will be kept longer, though none of the soldiers on the ground was quite sure what would happen to them under the new system.

Thus picking up hapless thieves -- called Ali Babas by both Iraqis and Americans -- has become the primary mission for many soldiers. The men of Company 4-64 had been patrolling their sector of the city on foot, but now they're going in Humvees. "We picked up 64 guys in two hours this morning," says Lt. Jason Redmon of Nashville, Tenn. "Our goal is 100 for a day." Redmon says other companies are doing the same thing all over Baghdad.

Finding the suspected looters isn't difficult, though sometimes it's impossible to figure out what they're trying to steal from the scorched hulks of the ministries and banks where they're arrested. Everywhere Redmon's Humvee goes to pick up men other soldiers have arrested, the unhappy would-be looters cry, "No Ali Baba! Me no Ali Baba!"

And, inevitably, some of them aren't. "I am not Ali Baba, madam!" cries a small old man in a baggy white shirt who was arrested at the TV station. "I am old man, I have a shop, I not need money. What will I tell my wife? I have four small children. I am swear." Of course, all the detainees say this, but several of the soldiers believe this one. "I think he got caught in the wrong place at the wrong time," says Sgt. Rogelio Gonzales. Later, the medic on duty says he might try to set the old man free, along with young Fathyl Bander.

Redmon was frustrated with the old system -- he would apprehend people only to see them on the streets stealing again days later, frightening the neighborhood people he's gotten to know. He says he recognizes many of the people he picked up Friday from previous run-ins. Still, he concedes, mistakes can be made -- especially when none of the arresting officers speak Arabic. "The hardest part," he says, "is knowing who's a criminal and who is just taking stuff out of their house."

Shares