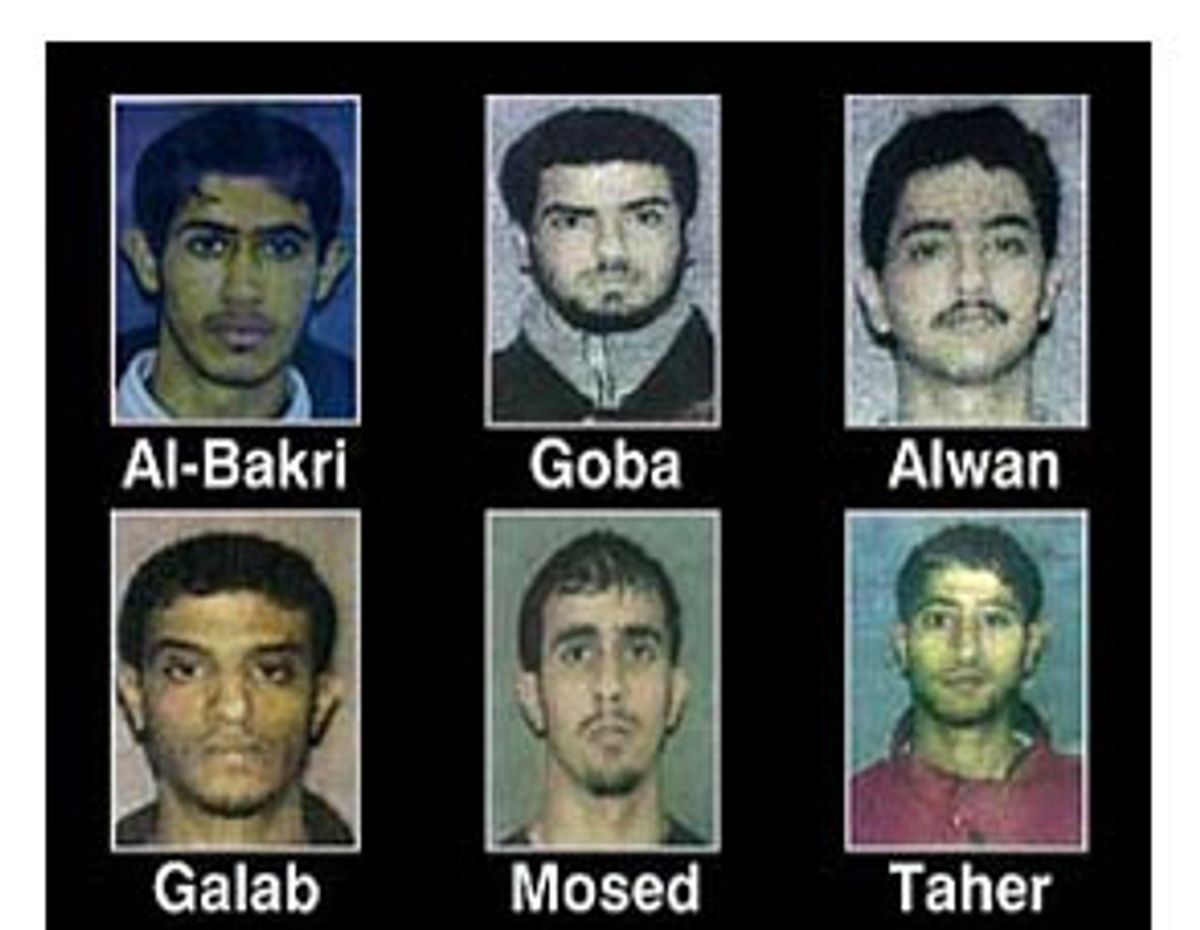

For many Americans, one of the few, true, uncomplicated success stories of the war on terrorism would be the FBI's arrest last fall of a "sleeper cell": six young Yemeni-Americans from just south of Buffalo, N.Y., who had trained with al-Qaida and had even heard a lecture by Osama bin Laden himself. President Bush gave the arrests key billing in his January State of the Union speech, when he bragged about "al-Qaida cells" that had been "broken in Hamburg, Milan, Madrid, London, Paris, as well as Buffalo, New York."

The providence of that bust seems only to have grown over time, as five of the six, one after the other, have accepted guilty pleas with the U.S. government. Just last Monday, Yasein Taher -- voted "friendliest" of Lackawanna High School's class of '96 -- entered into his agreement, pleading "guilty to providing material support to al Qaeda, a designated foreign terrorist organization," according to the Justice Department, and prompting some chest thumping from Attorney General John Ashcroft. "With today's conviction, the Department of Justice continues to build on its strong record of prosecuting those who provide material support to our terrorist enemies," Ashcroft said. "The cooperation we secure from defendants who trained side by side with our enemies in Afghanistan and elsewhere is valuable as we continue to wage the war on terrorism."

Were the Lackawanna Six really a "sleeper cell"? Maybe. But even though the White House describes them as such, there is no direct evidence to support the charge; an FBI source points out that no one from his office has said such a thing in public.

Not only has the FBI not officially called them a sleeper cell, the U.S. attorney's office hasn't even charged them with conspiring to hurt anyone -- the evidence shows they attended an al-Qaida training camp in the late spring or early summer of 2001 -- but not with anything indicating that they were a definite threat: no orders received, no plans to strike. But all will be behind bars for the foreseeable future. All six insist that they love America and mean it no harm, but the government has threatened other charges -- even the capital offense of treason.

They have all felt pressure from the Department of Justice to plead to charges. Otherwise, prosecutors can't promise that they won't add weapons charges to the mix or -- even worse -- that the Pentagon won't designate them "enemy combatants," like Jose Padilla, and ship them to Guatánamo Bay forever.

The six are the subjects of the Justice Department's aggressive new policy to make arrests -- and process convictions -- even before hard evidence of terrorist plans are uncovered. It's a shift from prosecuting crimes to anticipating and preventing them, and it has as a clear drawback: Suspects will go to prison despite an irreconcilable ambiguity about whether they are actually enemies of the United States.

That's certainly the case with the five alleged terrorists from Lackawanna who have pleaded guilty. And all eyes are on the last one, Mukhtar al-Bakri. A former co-captain of Lackawanna High's soccer team, al-Bakri was arrested in September 2002 at the age of 22, just hours after his wedding, and his admissions to law enforcement set the stage for the arrests of the other five. The government deems him a terrorist threat. None of that quite squares with what the citizens of Lackawanna's Yemeni-American community -- numbering approximately 1,100 -- know of him: a nice guy who earned $300 a week as a deliveryman for Lackawanna's Unity Wholesale and who cheered for the National Hockey League's Buffalo Sabres.

Al-Bakri now sits in his cell at the Niagara County Jail. His family insists he wouldn't hurt a fly, yet the government has ensured that he remains isolated from the other prisoners. Indeed, the Six are deemed such a threat to the nation they've been housed in three separate prisons. Today at 2 p.m., al-Bakri -- who like the others faces a maximum sentence of 10 years in prison, a fine of $250,000, or both -- is scheduled to appear before U.S. District Judge William Skretny to enter into a plea agreement with the government, according to prosecutors. If all goes according to plan, the murky, complicated story of the Lackawanna Six -- and a mysterious cast of characters who have yet to be captured by federal authorities -- may never get a public court airing.

Most of the arrests stunned not just the Yemeni-American community in this town, but the larger community as well. The Lackawanna High School graduates -- some went on to Erie Community College -- played soccer in the park, shot pool at Crazy Eight Billiards on Abbott Road. Their fathers worked for Bethlehem Steel before the plant closed in the 1980s; all but one was born in the United States. They're family men. None was known for anti-Americanism; about as political as they got was to register as Democrats. They were the cool, assimilated guys in the community. "They had fun," attests Lawanda Albanah, 26, who attended high school with two of them. "They partied. They had girlfriends left and right."

Taher, a former all-star soccer player who co-captained the varsity Steelers, is a handsome, trim 24-year-old who raised local eyebrows when he married a former cheerleader -- a white girl -- with whom he has a 3-year-old son. He loved tooling around his hometown on his Suzuki motorcycle, dressed in baggy hip-hop attire. His bio was so all-American, in fact, that newspapers and at least one network morning show referred to him as a former homecoming king -- an honor he never won, according to his wife.

Or take Sahim Alwan, 29 when arrested, considered a clean-cut, articulate pillar of the community who worked with disadvantaged kids. The son of a steelworker, he earned $31,500 a year selling satellite TV systems, was quoted in the Buffalo News condemning the 9/11 attack and declaring that Muslims are "citizens of this country and we're proud of that." Before a 2002 pilgrimage to Mecca, Alwan called the local FBI to give them a heads-up.

But the Lackawanna Six were brought together by a seventh, shadowy figure named Kamal Derwish. Born in Buffalo, Derwish moved abroad as a kid, spending most of his life in Saudi Arabia and Yemen. The pious and intimidating 27-year-old returned to Lackawanna in 1998, where he became the angry conscience of the Muslim community. From the Yemeni owner of the Holland Street deli who sold pork -- considered an unclean food in Islam -- to the younger men who went out clubbing, Derwish chastised his brethren for straying from the righteous path.

He led independent study groups at the mosque, taught at an Islamic school on weekends. "He was looking for guys who are sincere, devout Muslims," a defense source says. "He told them that every Muslim has an obligation to be ready if Islam is attacked." Derwish recruited the Six and told them "about this place in Pakistan which would be a place for them to go learn about the Islamic religion," Albanah says. "Here in America we've got religion, but it's not a good religion. They could learn more back home."

Taher's attorney, Rodney Personius, says his client "went there because he was brainwashed, shamed and guilted by Derwish. He believed he had to do this in order to cleanse himself of his past sins and prepare for Allah." Those sins, Personius says, included drinking and partying, not praying enough and, worst of all, having a child out of wedlock with his non-Muslim common-law wife, Nicole Frick. Derwish slammed him for that and "Yasein bought it -- hook, line and sinker."

At least one other recruiter worked with Derwish -- a mysterious figure from Indiana identified previously only as "Juma." According to one source close to the investigation, his full name is Juma Muhammad Abdul Latif al Dosar. Known as Abdullah Juma at the Lackawanna Mosque, where he led prayers a couple of times, he said he and Derwish were old friends, that they'd fought together in Bosnia defending Muslims.

Juma, Personius says, was brought in to close the deal, get the Six to travel abroad for training on how to defend Islam.

No one should be surprised to learn that in 1998, al-Qaida was recruiting in the United States. Law enforcement officials assert that bin Laden had been trying since the '80s to get American Muslims to join his jihad, and not without success. Egyptian-born former U.S. Army Sgt. Ali Mohamed was jailed for helping to plan the 1998 bombing of the U.S. Embassies in Kenya and Tanzania, which killed 224. Former Silicon Valley car salesman Khalid Abu-al-Dahab, currently serving time in an Egyptian prison, is credited with recruiting 10 or more Americans into al-Qaida. In 1995, the two smuggled Ayman al-Zawahiri, bin Laden's chief deputy, into the U.S. for fund-raising. Around then, bin Laden's former personal secretary, Wadih el-Hage -- since convicted of perjury and conspiracy in the embassy bombings -- obtained U.S. citizenship and recruited in Texas, Oregon and Florida.

Since 9/11, the government has intensified its search. On April 14, Earnest James Ujaama of Seattle pleaded guilty to a charge of conspiracy to provide goods and services -- computer software -- to the Taliban. Last July, authorities arrested former Chicago gang member and Muslim covert Jose Padilla, alleged to have conspired to detonate a so-called dirty bomb. In August, four Arab men near Detroit with fraudulent passports were charged as members of a "sleeper operational combat cell." In October, four Portland, Ore., residents -- one a member of the U.S. Army Reserves -- were accused of trying to travel to an Afghan terrorist training camp after the 9/11 attacks.

Dr. Rohan Gunaratna, author of "Inside al-Qaeda: Global Network of Terror," tells Salon that throughout the 1990s, al-Qaida recruiters favored areas where Muslim immigrants live -- North Jersey, Brooklyn, Dearborn. "The threat is of those individuals that have gone through those training camps since 1996 that have scattered around the world," Dale Watson, a former FBI counter-terrorism official told the Senate last September. "Where are those people? Are they living in Texas? Are they living in Montana?" Up to 100 recruits may still be living in the United States, terrorism experts say.

Once Derwish assembled the Six, he put up thousands of dollars to fund their travel to Pakistan, Personius says, though a law enforcement source says that the money trail is still being investigated. In March 2001, Shafal Mosed, 25, one of the best goalies in Lackawanna High history, visited a travel agent to order airline tickets to Lahore, Pakistan, for himself, Faysal Galab, 27, and Taher; all three later paid with cash -- $1,309.20 apiece.

Taher ran into his uncle, Abdul Noman, the day of their flight, April 28, 2001. "I'm going to study the Islamic religion," he said.

"Allah be with you," Noman replied.

Mohamed Albanna -- the father of Galab's fiancée, Aisha, and the vice president of the local chapter of the American Muslim Council -- says he found out about the trip at the last minute, and he wasn't happy. "Their language barrier wasn't going to be beneficial for them to learn anything religiously," Albanna says. "And I personally wasn't thrilled because my daughter just had a baby and he [Galab] was leaving her with two kids, which is not the right thing to do. Having said that, if they want to make a religious trip, they're entitled to it."

Mosed, Galab, and Taher flew from New York to Lahore. About a week later, they were contacted by an emissary from Derwish who took them to Kandahar, Afghanistan.

On May 12, the other three -- Alwan, al-Bakri, Yahya Goba, 26, plus a seventh man from the neighborhood, Jaber Elbaneh, 36, a nephew of Mohamed Albanna -- flew to Quetta, Pakistan, where they met Derwish. They, too, then traveled to Kandahar.

In both places, missionary Islamist scholars of Tablighi Jamaat lectured them -- about prayers, but also teaching more extremist dogma like the al-Qaida view of Muslim struggles in the Palestinian territories, its stand against Kashmir, and justifications for suicide bombings. They watched a videotape about the bombing of the USS Cole. All six eventually traveled southwest of Kandahar, to the al-Farooq training camp.

Much of the al-Qaida recruitment video shown on cable news channels after 9/11 was filmed at al-Farooq. Terrorists in training fired Kalashnikov rifles at pictures of then-President Clinton, ran obstacle courses, blew things up. "American Taliban" John Walker Lindh arrived at the camp just as the Lackawanna Six were leaving. Months before, two Saudi recruits, Wail al-Shehri and Abdulaziz al-Omeri, trained there before tackling their final task -- propelling American Airlines flight 11 into the North Tower of the World Trade Center.

The Lackawanna Six were there before 9/11. Nonetheless, Alwan had misgivings, he said in a court statement. "After realizing the crazy, radical mentality of the people at the camp," on the fifth day of training he decided he wanted out. Crying, he asked a guard if he could leave but was rebuffed. He couldn't leave without permission; the camp was "out in the wilderness" and he wouldn't "know where to go or how to return to Kandahar or any place else," he said in the statement. He faked an ankle injury. On his 10th day there he was released, riding in a pickup truck to Kandahar, where he stayed in a guest house for two days before taking a minivan to Quetta.

Something else happened in Kandahar, however, which Alwan didn't readily admit.

- - - - - - - - - - - -

Last summer, a member of Lackawanna's Yemeni community wrote to the FBI's Buffalo office expressing concern about the trip the Six had taken the previous year. In July, federal authorities interviewed Mosed and Taher; they acknowledged having studied religion in Pakistan but denied traveling to Afghanistan. But U.S. intelligence agencies began conducting surveillance on them, discovering that Mukhtar al-Bakri was in Bahrain to prepare for his arranged marriage and that he kept in touch with Derwish in Yemen via e-mail. The authorities knew Derwish was a terrorist. Was al-Bakri one, too? They wanted to find out.

"Goodbye," al-Bakri said in a tapped phone call to a friend before his Sept. 10, 2002, wedding. "You won't be hearing from me again."

Concerned by what sounded to authorities like a pre-jihad farewell, intelligence agents began reviewing his file. On July 18 he'd sent an e-mail to a friend in Buffalo:

Subject: The Big Meal

How are you, my beloved? Allah willing, you are fine. I would like to remind you of obeying Allah and keeping him in your heart because the next meal will be very huge. No one will be able to withstand it except those of faith. There are people here who had visions and their visions were explained that this thing will be very strong. No one will be able to bear it.

Alarmed, intelligence shared the information; even the Oval Office was briefed. Now cooperating with the government, Lindh said that at al-Farooq he'd heard talk about a group from Buffalo. Some in the FBI wanted more time to build their case, but, using post-9/11 reasoning, Ashcroft pressured the feds to take action before it was too late.

Al-Bakri had been married only a matter of hours when Bahraini authorities -- acting on a request from Washington -- arrested him. They "kicked in the door, ran him to the ground, beat him and threw him in prison," his attorney later complained. His new wife burst into tears.

One day later, officials from the FBI's Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, legal attache arrived at al-Bakri's Bahrain prison. They asked about his e-mail alluding to "the big meal"; he said that he was just passing on remarks he'd heard during a trip to Saudi Arabia.

And the phone call about dropping out of sight forever? He was just submerging himself into the world of a married man, he insisted.

But though he at first denied having gone to Afghanistan in 2001, al-Bakri soon broke, admitting their trip to al-Farooq, their training with al-Qaida. At the camp he'd been assigned a code name -- "Abu Omar Alyafei" -- and was trained in the use of handguns, long-range rifles and Kalashnikov assault rifles.

At once, back in Buffalo, FBI Agent Ed Needham -- one of about 70 agents in the local office -- paid a visit to Sahim Alwan, whom he knew from the investigation and from Alwan's call before leaving for Mecca. Once he'd heard what al-Bakri had said, Alwan admitted the trip as well. With that, the FBI and local police began making arrests. It was a huge story. Al-Bakri was flown home and charged within hours.

Prosecutors were confident they could convict the Lackawanna Six of violating a 1996 law against providing material support to a terrorist group, but they wanted to build a stronger case. Searches of the suspects' homes yielded audiotapes containing anti-U.S. and anti-Israeli rhetoric, an unlicensed .22-caliber handgun, a stun gun, evidence of the use of aliases. Mosed had told police that he only had around a thousand dollars to his name, but at his home cops found $6,400. At Nicole Frick's apartment was a nine-page document about suicide operations, stating that "the objective is to kill as many of the enemy as possible, and he will almost certainly die." Suicide bombing is the preferred method to fight infidels, the booklet stated: "No other technique7strikes as much terror into their hearts."

Defense attorneys argue that the tapes reference common points of Muslim culture, and in any event are legal. The $6,400 found in Mosed's house belonged to his wife, his lawyer says. Taher's nine-page document, Personius says, is simply a scholarly treatise on suicide bombing in Chechnya.

The government later acknowledged overreaching on one matter. Prosecutors removed remarks taken from the tape of "Koranic Recitations" as evidence of malicious intent. Such a charge, after all, could be made against anyone with a Koran.

- - - - - - - - - - - -

Recently, I walked around three successive Lackawanna streets -- Wilkesbarre Street, Holland Avenue and Ingham Avenue -- where five of the Six lived. Of the residents who agree to speak to me -- and many don't, claiming not to speak English (though "no comment" rolls off the tongue) -- there are two common themes. One is that the government has invented the entire case in order to persecute Muslims. "It's a scam," says Mohamed Abdul-Jabar Alshish, 16, tossing a football with his friends outside the Lackawanna Mosque. "They're really good kids," says Saleh, who won't tell me his last name. Is it persecution of Muslims? "That's what I think, yes."

The other argument you hear accepts the trip as fact, but insists the men were hoodwinked and harmless. "They attended the camp by mistake," says Abdul Noman, 40, Taher's uncle. "They went there, and then they realized it's not right, so they came back. When Yasein came back, he told me that he'd never appreciated this country more." They'd gone to learn about Islam and how to defend Islam in Bosnia, Chechnya, the Palestinian territories -- not how to kill Americans. "It's unfair," seconds Saleh Mohamed, a hospital employee. They never "had the intention of harming human beings."

Others from the area -- non-Muslims, primarily -- view it differently. "Certain things occur to you after this happened," says Judy Chmielowiec, who lives across the street from Taher, her sons' former classmate. "They always had $30,000 cars. We're working three jobs and we can't afford that." (Taher's brother owned an Infiniti, but he's facing drug-trafficking charges, which may explain suspicious income.)

While the mothers of the defendants are "in denial" about their sons confessed deeds -- according to Dr. Khalid Qazi, chairman of the Western New York chapter of the American Muslim Council -- the trip to the camp is undisputed. At 3 a.m. there was the wake-up; 4 a.m., prayers; 5 a.m., physical fitness; 6:30 a.m., breakfast followed by nap; 8:30 a.m. to 11:30, military lecture; 1 p.m., lunch followed by prayer, then cleanup. Military instruction: mountain climbing, handguns, rifles, Kalashnikovs, the puttylike plastic explosive C-4 -- used in the bombing of the USS Cole, a version of which "shoe bomber" Richard Reid tried to ignite. Dinner, prayer, bed. It seems that five of the Six -- minus the injured Alwan -- performed guard duty.

Though their trip preceded 9/11, bin Laden was already a dangerous enemy of the U.S., responsible for the bombing of the Cole and the embassies in Africa. And he came to al-Farooq to speak. Speaking to all 200 or so recruits there, bin Laden espoused anti-U.S. and anti-Israel rhetoric. He lauded suicide attacks as a legitimate tool against the enemy and claimed responsibility for the embassy bombings. And he promised more: 50 members of al-Qaida had been sent to attack America.

Taher didn't understand the Arabic bin Laden was speaking, so others told him what he had said. Some things got through to him, however; according to Taher's plea agreement, "one trainee at the camp asked for volunteers to sign up for suicide missions."

Upon their return, the Six didn't tell any of the authorities any of this. They claim to have ceased contact with that world.

But Juma stayed with Yahya Goba until right after 9/11, when he went to Afghanistan to fight the Americans.

In September 2002, assistant U.S. Attorney William Hochul mocked the defendants' pleas of helplessness. "'I was duped, I was going to Pakistan, all of a sudden I was going to Afghanistan,'" he said in a bail hearing. "They get back to the United States -- do they say anything?"

Some see more simple human frailty in their reticence. "I think it would be difficult to come forward and say, 'You know, I was with the most wanted terrorist in the world,'" says the AMC's Qazi. "When you realize you've made a major blunder you don't necessarily go around telling people about it," agrees Patrick Brown, attorney for Shafal Mosed.

Still, the question remains: As the prosecution put it in one of their first filings last fall, "Why do a group of young Yemeni Americans, born and brought up in Lackawanna, New York, and, in the majority of cases married with children, suddenly leave their otherwise unremarkable lives to spend six to seven weeks in a terrorist training camp, then quietly slip back into roles of middle-class Americans?"

But there seemed enough gray area for Magistrate Judge Kenneth Schroeder to grant Alwan his request for bail last fall, swayed by Alwan's early exit from the camp and anti-al-Qaida statements. But that all changed on Jan. 10, 2003, when another one of the Six -- used-car salesman Faysal Galab -- entered into a plea agreement with the government.

Galab copped to the different crime of "contributing funds and services to specially designated terrorists, in violation of the International Emergency Economic Powers Act" -- having paid cash for a green uniform -- but not the "providing material support" charge leveled against the others. "It's the same as if he brought back cigars from Cuba," insists Joseph LaTona, his attorney. "He wasn't planning, plotting or scheming in any way."

Galab had some interesting news about at least one of his pals. One of the Lackawanna Six had had a private face-to-face with bin Laden: Sahim Alwan.

Alwan's bail offer was immediately revoked.

In fact, Alwan had spoken with bin Laden twice, in two different Kandahar guesthouses: in May 2001, on his way to al-Farooq, and in a private meeting after leaving the camp in June. According to an account from Alwan's attorney, James Harrington, at the latter meeting the two sat on the floor. Bin Laden asked Alwan what Muslims in the U.S. thought of "martyrdom operations." Alwan said it wasn't something Americans much thought about.

A long pause.

"How are your brothers doing at the camp?" bin Laden asked. All right, he replied.

"Why are you leaving?" bin Laden asked. Alwan said he missed his family.

Bin Laden was surprisingly soft-spoken, he thought.

"Bin Laden wanted Alwan to reconsider and continue training at the camp, and Alwan told him he couldn't," said Harrington. He denied that Alwan hid anything from investigators; no one ever asked if he'd met with bin Laden. Harrington even tried to cast the meeting with bin Laden as evidence of Alwan's allegiance to the United States. "Despite the pressure of a face-to-face meeting with one of the most powerful and negatively influential men in the world, Mr. Alwan continued home from Afghanistan and was not swayed," Harrington said to the court.

Galab was just the first of the Six to act on his fear of additional charges the government might file -- especially as an "enemy combatant" held without trial, the right to an attorney, or necessarily even a formal charge. Lawanda Albanah says that her cousin Aisha, who's engaged to Galab, told her that Galab's attorney pressured him to enter into the agreement. LaTona, the attorney, disputes this.

Mosed pleaded guilty on March 24. Goba did the same on March 25.

"Look," says Brown, Mosed's attorney, "there was an executive order by President Clinton saying they were not supposed to go, so they ought to take their lumps for it. But that doesn't make them terrorists."

Alwan pleaded guilty on April 8. He also admitted having delivered two videotapes about the bombing of the Cole from the Kandahar guesthouse to an al-Qaida associate in Pakistan

Taher pleaded guilty on May 12. Al-Bakri -- the one whose confession set the dominoes in motion -- will be the last one to fall, as he's scheduled to plead guilty today. All should receive sentences between seven and 10 years in prison.

Recruiter Kamal Derwish might be able to shed light on exactly what the Lackawanna Six were planning, if anything, but his testimony won't be forthcoming. On Nov. 3, 2002, he was on a remote Yemen highway with the head of al-Qaida's Yemen operations, long wanted in connection with the attack on the USS Cole.

An unmanned CIA Predator aircraft took aim. A Hellfire missile was fired. Direct hit. Everyone was killed.

Rumors swirl that Juma was arrested in Afghanistan during Operation Enduring Freedom and is currently being held in Guatánamo Bay, which the Defense Department will not confirm. Mohamed Albanna -- uncle of Jaber Elbaneh, the seventh man -- says that he hasn't heard from his nephew since he left for the camp in 2001. (Mohamed Albanna has his own troubles, of course. In December he and two relatives were arrested as part of "Operation Green Quest," the federal crackdown on the illegal money-transfer systems in the Muslim world known as hawalas. The three are alleged to have sent almost $500,000 illegally to Yemen.)

After all this probing and confession, it seems nothing short of remarkable that the question still stands: Were the Lackawanna Six an al-Qaida cell? "You can see that they were not an immediate and a direct threat to the United States because they were not 'missioned,'" al-Qaida expert Gunaratna says after reviewing their case for Salon. "But the very fact that they have been trained and the very fact that they have been in that environment would make them a potential risk."

"There are several thousands of people like this," Gunaratna says. "They have come to the West and they have not been given a mission." But that doesn't necessarily matter, he says. "There need not be a direct order. The environment itself could motivate any one of them to go and do something."

"These guys couldn't even organize a picnic," counters Noman, Taher's uncle.

Even with all the plea agreements, defense attorneys point out that the 1996 law in question that their clients violated -- providing material support by providing "personnel" in the form of their own person -- has yet to be reconciled by the courts. It was ruled unconstitutional in California but passed muster in a Virginia courtroom during the trial of Walker Lindh. The law could be tested, but that would require years and a client willing to put himself through an extended period of uncertainty.

In his plea agreement, Alwan told the government that a second group from Lackawanna was considering a trip to al-Farooq. The government has yet to name any in this second group, though Alwan's attorney says that they didn't actually make the trip. Still, prosecutors made sure to point out this second group; could they be charged with planning to go? "I certainly don't think so," Harrington says, "but who knows with this administration."

A Justice Department source says that unsatisfying resolutions like that of the Six are the future of terrorism prosecutions. "There is a predisposition not to wait a build a case the way it used to be done," the source says. Now there's a "prevention paradigm -- it's Ashcroft specific and Ashcroft driven."

The moment law enforcement has enough evidence to arrest and detain, it will. "What that means is sometimes the cases aren't as strong as if we had waited another five and six months to gather other types of evidence, particularly electronic evidence," the source says. "We really don't want to wait until these people are about to fly a plane into a building."

Shares