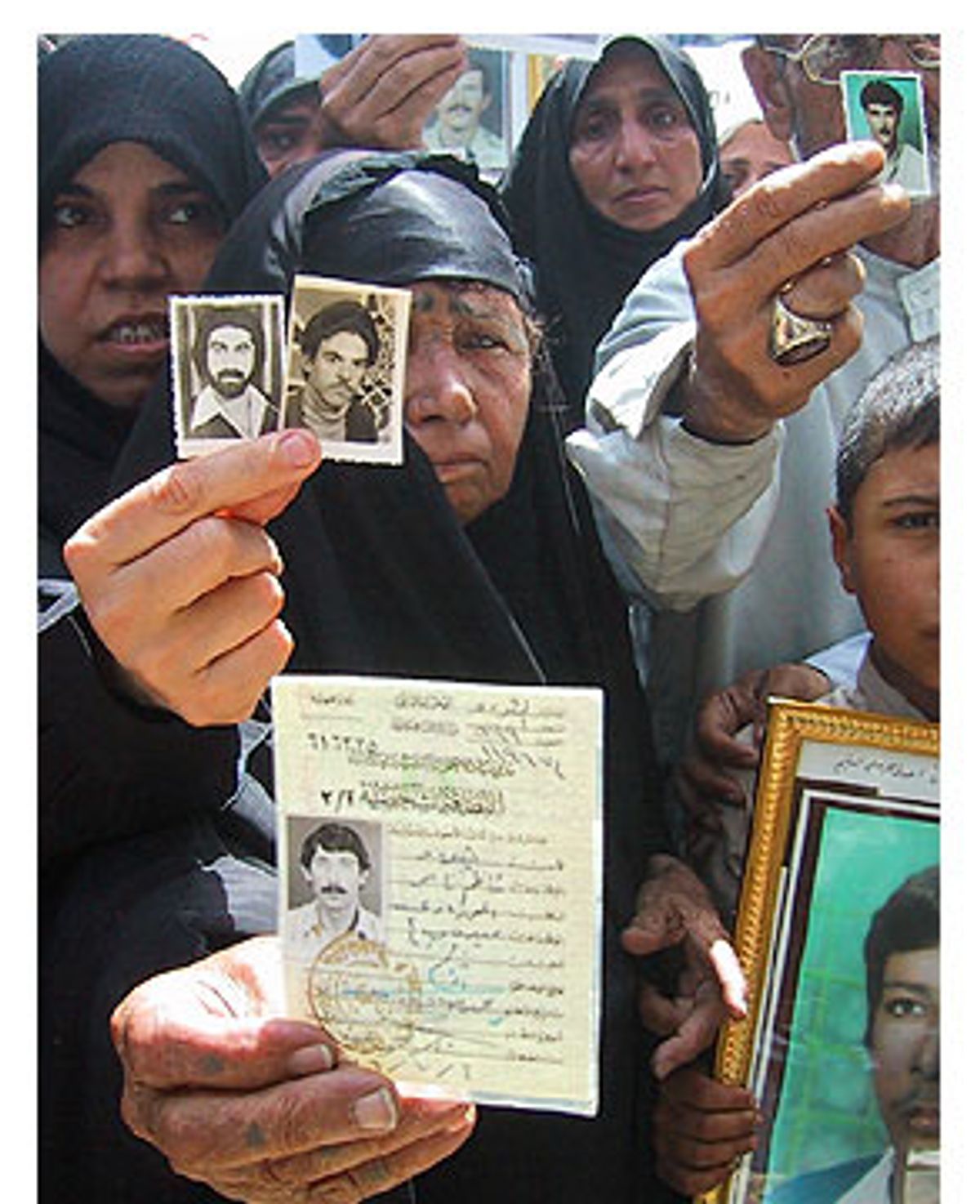

More than a hundred Iraqis are marching down the street in front of the Palestine hotel, many of them holding portraits of relatives murdered by Saddam Hussein's Baath regime. The marchers crowd around anyone who will listen, offering up the details of their losses. Name after name is cried out into the searing air. A 50-year-old man with a trim gray beard recounts the five years he spent in an underground prison and the 10 members of his family who were killed. Small wrinkled women in black chadors thrust forward identity cards belonging to disappeared sons. Another man holds out a worn Arabic document taken from the Abu Graib prison after Baghdad fell, indicating that his two brothers were hanged there.

These people want their loved ones remembered and their agonies acknowledged, but they also want some semblance of justice. Right now, though, they see members of Saddam's regime boldly going about their lives with no apparent fear of reprisal. "They are changing themselves like snakes to stay in the same positions in ministries," says a protester named Allah Hussein. A tall young man holding aloft black-and-white photos of his murdered father and uncle says, "We want to catch the Baathists and punish them here in Iraq."

Such anti-Baath demonstrations have happened throughout Baghdad in the past few days, often several times a day. Iraqis who have been silenced for decades are desperate to talk about the crimes committed against them. For some, the continuing presence of Baathists in positions of authority adds another facet to their disappointment in the United States. It's often mentioned in the same breath with complaints about the continuing lack of electricity and security.

At the same time, protests against the Baath can deflect anger away from Americans, causing people to focus on 35 years of murder instead of 35 days of chaos. The demonstrations also provide catharsis and a way for Iraqis to begin to reckon with their bloody history, debating just how much of the old order needs to be extirpated, and what might replace it. The evils of Saddam's regime transcended the man -- he implicated many others in his crimes through a vast network of informers and apparatchiks. Now, victimized Iraqis are trying to identify those who were complicit in their oppression, and establish how their influence can be eliminated for good.

Even as the process of purging Baathism from Iraqi society gets underway, it is clear that much work needs to be done to rid the country of the party that has dominated every aspect of life for more than three decades. On May 16, Paul Bremer, administrator of Iraq's Provisional Authority, issued a proclamation on the "De-Baathification of Iraqi Society," under which members of the top three strata of the Baath Party "are hereby removed from their positions and banned from all future employment in the public sector," which includes hospitals, universities and government-affiliated corporations. The mandate, which affects about 30,000 people, also forbids the display of Saddam's image in public places and offers rewards for help in capturing senior Baathists.

Yet Iraqis continue to complain that top Baathists are holding on to their positions in government ministries. On May 19, a few dozen men from the oil ministry demonstrated in front of their building, claiming that Baathists are still in charge. "Yes, yes for freedom! Yes, yes for election! Yes, yes for Bremer! No, no for Baathists!" was their cheer. One of the protesters, Aubadi Al Shujeri, said his manager, who spied on employees for Saddam, "is a big thief. He's stolen all the money from the ministry and built many houses. He's still working in the same place."

Several employees identified deputy oil minister Medhat Abbas as a Baathist who embezzled money. Inside the oil ministry, the clerk at the front desk said Abbas isn't available, and then added that he agrees with all the protesters' charges. "Abbas was a Baathist. It's a disappointment that the same Baathists are still working here," he said, shrugging.

Later that afternoon, another group of workers held a protest near the Palestine Hotel, many of them also talking about their boss and the Baath Party. One held a sign that said, "Yes Yes Mr. Bush Man's peace." But it also was clear that they're not happy with Bremer's de-Baathification order. They don't want their boss fired. They want him reinstated.

The 30 or so men from the Transport Passenger Co., which runs busses in Baghdad and throughout Iraq, say they believe all senior Baathists should be removed -- except one. Company director Tawfeek Yaroub, said one protester, "is a very good man who always provided good things for us." Added another, "He helps us. For him, there's no difference between a rich man and a poor man. All the staff want Mr. Yaroub to return."

Yaroub lives with his wife and three children in a modest one-story cinderblock house in a neighborhood of government employees. Several days ago, an American official told him not to return to work. A short, rotund man in a plaid shirt and blue slacks, he has worked in transportation all his adult life, first in the Transportation Ministry and then at the bus company. His exhausted-looking wife, a teacher turned housewife, says her husband loved his job and often worked through the night. "For 13 years, I didn't see him," she says. "He was always at the ministry, always on duty."

"The Americans should keep the good men to build Iraq again, not treat them like the others who killed," she continues. "Not all the Iraqi people are bloody. People in Iraq couldn't obtain a good position until they joined the Baath party. Surely many were bloody, but there were many honest people -- teachers, doctors, clerks -- who didn't commit any crime."

Yaroub, who is quieter than his wife, seemed less indignant. She urged him to go to the protest held on his behalf, but he refused. "I can't go and ask to come back again. I respect the decision of the Americans," he says.

To Entifadh Qanbar, the spokesman of the Iraqi National Congress, Yaroub's touching story sounds like a clever Baathist plot. "I doubt the demonstration is legitimate," he says. For the INC, a group of powerful dissidents that aspires to lead the new Iraq, there's no such thing as an innocent Baathist. "It's a party with a Nazi ideology that's completely unacceptable in any civilized society," Qanbar says.

The INC actually coined the term "de-Baathification," after postwar Germany's de-Nazification process, which aimed to root every element of the Third Reich out of the country. Daunting as de-Nazification was, though, de-Baathification will likely prove even harder. The Nazis, after all, controlled Germany for only 12 years, and after World War II, the people retained a culture that predated Hitler. The Baath Party ruled Iraq for nearly 35 years, enveloping every aspect of the country. Moving ahead in Iraqi society meant moving ahead in the party. Everyone who ran a ministry or government office was a high-level Baathist. The education college in Baghdad was only open to Baathists, meaning all the country's teachers are party members. Iraq has no civic culture besides Baathism.

To the INC, that's all the more reason to start eradicating it now. The party is thrilled to see its program enacted by Bremer, whom they regard as a huge improvement over his predecessor, Jay Garner. Qanbar says that postwar chaos has led to whispers of nostalgia for Saddam's regime, making it all the more crucial to destroy every remnant of the old order, lest some Baathists attempt a resurgence.

"A gentleman came to us and said his 12-year-old daughter has a teacher who's a Baathist," Qanbar says. "The teacher said, 'Saddam was a good man. He's coming back, and you should kill Americans.' This shows you that any remnant of the Baath is not acceptable."

Qanbar is a clean-shaven man who wears a black shirt with gray pinstripes and matching pants with a pistol tucked in back. He sits outside in the INC compound in the former Baghdad Hunting Club, a place swarming with armed hangers-on, reporters, robed tribal sheiks and assorted other frowning characters. To him, it seems preposterous to suggest that any Baathist has expertise needed to run Iraq. "No industry will be crippled if the Baathists are removed," he says. "They haven't been functioning as professional technocrats -- they've been enslaving professional technocrats."

Qanbar adds, "I've talked to Iraqis across the board. One issue all Iraqis are concerned about is the issue of de-Baathification."

Plenty of Iraqis, though, are far more concerned about the issue of electricity. Summer has just begun, Baghdad is roasting, and people aren't used to living without air conditioning, fans or any respite from the oppressive, dust-filled air. Even without the gunfire that crackles intermittently all night, it would be hard to sleep. Lingering vestiges of Baathism, said a bystander at a protest on May 18, "aren't a big problem for us. We want electricity and water. After that we can sleep and feel safe."

The May 18 protest was called in a traffic circle where a statue of Iraqi's former president, Ahmed Hasan al-Bakr, glowered over the street. Bakr, who ruled from 1968 until 1979, was Iraq's first Baathist president, and he brought Saddam to power. Still, some Iraqis remember him as a just and honest man. Before the demonstration had even begun, word went out that people were going to tear down the statue, and a dozen or so Iraqis arrived at the site to defend it.

"He's good. For what they want to remove the statue?" said 28-year-old Sajad Abbas. "My grandfather and father told me about him. He is honest and fair. We love him. We want to see that statue here."

Soon, though, a procession of a dozen or so anti-Baathists appeared, carrying banners written in Arabic and perfect English: "No Mercy With Saddam's Regime." "Exterminate Baath Criminals." "Common Graveyards Are the Greatest Achievement of Al-Baath in Iraq." More and more people arrived, until there were several hundred sweating under the ferocious afternoon sun. No one seemed to know who called the demonstration, and the men hoisting the signs insisted it was a spontaneous citizens' action. Frustrated, the statue's defenders wandered off.

"If anyone wants this statue to stay, he's a criminal!" screamed a burly, bearded man in a brown button-up shirt. A Shiite imam showed up and started giving interviews to the TV crews that began to assemble, saying that Bakr is the symbol of all Baathists. Saddam, he said, murdered his father. A man in a yellow oxford shirt climbed the statue and called, "Everybody who wants to tear down this statue, raise your hand!" Hands went into the air, and a chant erupted, "Fall down! Fall down! Fall down!"

When a crane finally arrived, it quickly snapped the head off the statue. The bearded man grabbed it and dashed wildly through the street while others chased it to hit it with shoes. A man in the crowd said, "Saddam killed my friend. George Bush is a great man. He's like the X-Men." Hearing that, another man, a mechanical engineer, came forward and said, "Saddam was the original dictator, but Bush is the global dictator. We love the American people, but we hate the government."

By dusk, all that was left was another empty pedestal topped with mangled metal.

Two days later, another protest takes place at the Palestine. Around a hundred workers from Baghdad's electrical stations, some in blue jumpsuits and hard hats, demonstrate against Baathists who refuse to vacate their positions. They carry signs denouncing their managers -- Dr. Keream Waheed, Muhsin Taher and Ahssan Rafeek Jewad. "They haven't fired anybody," says one worker. "The managers are coordinating with the coalition troops to stay in their jobs." Adds another, "Where are the promises of liberation?"

Around the corner, hawkers sell Saddam Hussein watches to kitsch-hungry foreigners. Aside from the Iraqi dinar, they're about the only place in Baghdad where Saddam's picture has been left intact. Clearly, the second part of Bremer's proclamation has been enacted -- Baath images are disappearing. At this point, only the Baathists themselves remain.

Shares