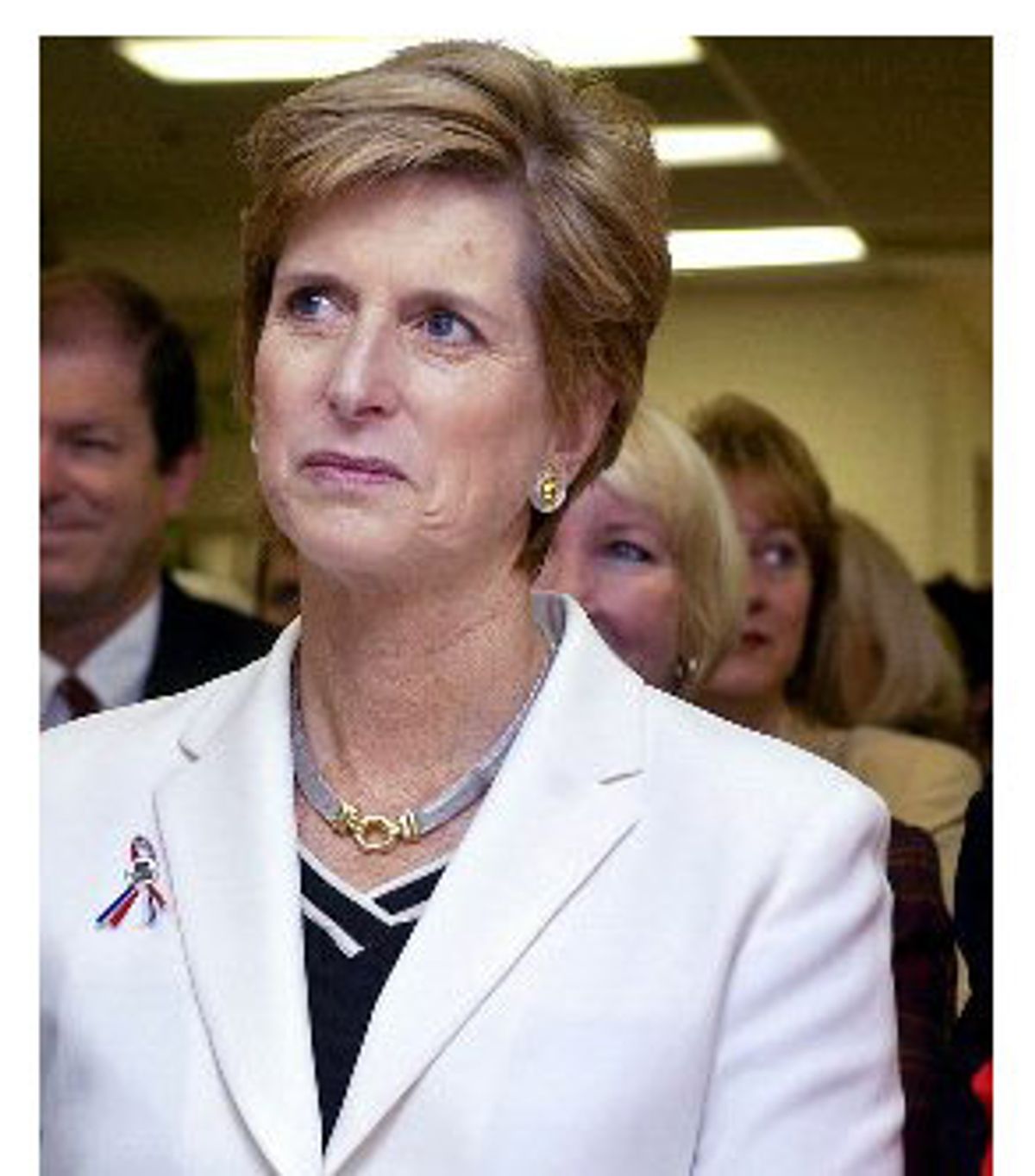

It was pretty clear to Hazel Gluck, a friend and former New Jersey campaign official close to Christine Todd Whitman, that the woman in charge of the Environmental Protection Agency had grown "exhausted," in part because of her long-standing battles with pro-growth conservative forces in the administration -- forces that almost always won.

But it was with characteristic loyalty and abject refusal to admit anything but sheer delight with the Bush administration that Whitman finally resigned Tuesday, writing to President Bush that she wanted to "return to my home and husband in New Jersey, which I love just as you do your home state of Texas."

The letter, released Wednesday morning, claimed "significant improvements to the state of our Nation's treasured environment" and announced a departure date of June 27. In a statement, President Bush called Whitman "a trusted friend and advisor" and "a dedicated and tireless fighter for new and innovative policies for cleaner air, purer water, and better protected land."

Inside the Beltway there was talk -- based upon conjecture and Whitman's losing battles with conservatives in the administration -- that Whitman was shown the door; Whitman, meanwhile, has maintained that the president had tried to talk her out of her decision and others backed this account. "I don't believe she was in any way pushed out," said Rep. Jim Greenwood, R-Penn., a moderate and No. 2 Republican on the House Energy and Commerce Committee's subcommittee on the environment and hazardous materials. "The information I have is that the president tried to get her to change her mind" and that Whitman quite simply misses her husband of 29 years, financier John Whitman.

Keith Nahigian, a friend and former aide, said that from her first day at the EPA she was talking about how much she missed her husband and the home where she grew up. She spends so little time with her husband, Whitman has jokingly complained that "it felt like they were dating again. They'd go out and it was like, 'So, what's going on with you? What are your interests?'" She also missed the family's 230-acre estate and farm in Oldwick, in northwest New Jersey, known as Pontefract, where she grew up.

Gluck also says Whitman was excited to be returning to the Garden State. But she described her as "tired and exhausted," and the exhaustion was not only due to how hard Whitman has worked and how far she's traveled since taking office at the beginning of the Bush administration. "Some of the right wingers in our party really make it difficult for [Secretary of State] Colin Powell and for anybody who's a moderate in this administration, and Christie was no exception," Gluck said. While Whitman enjoyed a "great" personal relationship with the president, the "pressure from the right wing" wore on her.

"The pressures of the job are enormous," Gluck says, "but this particular one with all the philosophical tugs, had to be part and parcel of what makes one tired." Asked to elaborate and describe conversations she'd had with Whitman to illustrate the point, Gluck demurs.

Another GOP moderate, Rep. Christopher Shays, R-Conn., says: "This was not unexpected.

"She did her best to be true to her principles and to serve the president," Shays said, "but the bottom line is that the president makes the environmental policy."

Whitman's departure is the second such notice announced this week by a high-ranking Bush administration official, following the notice. Monday by White House press secretary Ari Fleischer. Whitman told White House chief of staff Andy Card two weeks ago that she was mulling this decision, and Tuesday she told the president she had decided it was time to go.

Both Whitman and Fleischer are Bush loyalists, but the job always came much easier to the latter, who apparently never disagreed with one thing the president has ever done. Whitman, conversely, was constantly seeing her moderate environmentalism overruled.

From the beginning of the Bush administration, it was clear that Whitman stood in left field on Bush's team. And it was there -- alone and isolated -- where she often found herself.

After a Senate hearing on Feb. 27, 2001, Whitman said that "there's no question but that global warming is a real phenomenon, that it is occurring." Flooding and droughts "will occur" as a result, she declared. "The science is strong there." She suggested administration support for laws to cap the emission of the greenhouse gas carbon dioxide. In a confidential memo to the president on March 6, 2001, Whitman urged the president to address the issue of global warming since it "is a credibility issue for the U.S. in the international community" and "we need to appear engaged" in negotiations over the Kyoto Protocol to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

Many conservatives, however, think of global warming as quite a question, doubt the science, and oppose such a cap -- even though on the campaign trail in 2000 President Bush had promised to reduce carbon dioxide emissions from domestic power plants. By the Bush administration's first Earth Day, in April 2001, the president had broken his campaign pledge about carbon dioxide, had signaled that the government would withdraw from the Kyoto accord, suspended cleanup regulations for mining companies, and suspended the regulations on arsenic in the drinking water that were signed into law in the 11th hour by the outgoing Clinton administration. Whitman was given the task of announcing the suspension of the arsenic regulation, then was sent out to reverse the decision once it was used as shorthand, sometimes unfairly, by the media as a symbol of an administration hostile to any environmental concerns. Long before 9/11 changed everything, Bush's environmental record was a major subject of discord, and Whitman was in the thick of it, usually to her detriment.

After some Clean Air Act laws were relaxed last November to benefit coal-fired power plants, for instance, Sen. Joseph Lieberman, D-Conn., called for her resignation, and angry messages were issued by the National Wildlife Federation, the Natural Resources Defense Council and the American Lung Association, among others.

Whitman was generally perceived as one of the more out-of-the-loop and impotent Cabinet officials. In June 2002, the EPA sent to the United Nations a "Climate Action Report" that blamed human activity for global warming. President Bush said he disagreed with the report, which he dismissively described as having been "put out by the bureaucracy." A week later, Bush rolled back "New Source Review," a provision in the Clean Air Act requiring some industries to embrace sometimes costly cutting-edge environmental technologies. Whitman had embraced "New Source Review" as governor of New Jersey, so the move was seen as a direct rejection of her views. "This decision is a victory for outdated, polluting power plants and a devastating defeat for public health and our environment," said Sen. Jim Jeffords, I-Vt.

Still, Whitman seemed to perceive life as having improved somewhat from the lightning-rod first months of her tenure. In 2001, she had told the New York Times that Secretary of State Colin Powell referred to her as a "wind dummy."

"It's a military term for when you are over the landing zone and you don't know what the winds are," she explained. "You push the dummy out the door and see what happens to it." In January of this year, Whitman told the National Journal that she didn't feel "as much" like a wind dummy. "That was back when we had both the arsenic and the Kyoto issues," she said, "which were the big ones out there. We've been able to ratchet down over here so we haven't been quite as visible." The controversies she'd experienced, she said, were because "it's a terribly emotional issue. And for some people, you can never, ever, ever do enough. For other people, anything you do gets in the way of progress."

In her resignation letter, Whitman not surprisingly chose to focus on her greener pastures, citing administration regulations to reduce pollution from nonroad diesel engines; the Clean School Bus USA initiative, which plans to ensure low-emission school buses for every student by 2010; the proposed Clear Skies Act of 2003 to reduce pollution from power plants; and an EPA plan to clean up PCBs from the Hudson River. These are the kinds of measures that have brought her under fire from various conservatives, who see the Bush administration's occasional nod toward environmental concerns as weak and something of a betrayal.

"She was just a carbon copy of anybody who's ever been head of the EPA," said Fred L Smith Jr., founder and president of the pro-growth Competitive Enterprise Institute. Smith says that EPA administrators traditionally "regard as their duty to figure out what the green lobby wants and to implement it as quickly as possible" to the detriment of the nation, and Whitman was no exception. "This presents a dramatic opportunity for the administration to put someone in place to reinforce the changes already put forward in Congress," where, according to Smith, for the first time in decades the members of the House and Senate leadership "aren't part of the green establishment. They're not locked into the view that the only way you can protect the environment is to lock businessmen in jail and pass more regulations."

With such sentiments being voiced from the right, it's therefore not all that surprising that Bush's green opponents expressed not entirely anti-Whitman notions, a sort of "What's a nice green girl like you doing in a place like this?" Even Lieberman, who had called for her resignation last year, said "it would be a welcome change if Gov. Whitman's successor not only shared her interest in environmental progress, but were allowed to pursue it. But I won't hold my breath, though we may need to do that to survive this administration's clean air policies."

Phil Clapp, president of the National Environmental Trust, said that "no EPA administrator has ever been so consistently and publicly humiliated by the White House." Though Whitman may have fought for the cause on occasion, he said, in the end too often "the White House listened more often to industry lobbyists than to its EPA administrator." Democratic National Committee chairman Terry McAuliffe quizzically likened her to "a fish out of polluted water from the minute she stepped into the Bush Cabinet." True to überloyal form, Whitman appeared on CNN Wednesday morning and denied that she was "leaving because of clashes with the administration. In fact, I haven't had any." Regarding reports of any conflicts, Whitman allowed that "there's always give and take," but "that doesn't mean that you're having a battle about it."

Greenwood, who voted against the Bush administration's request to allow oil and gas exploration in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, seconded Whitman's take on the policy debates. The EPA chief "brings pretty green recommendations to the administration, and others whose job it is to represent industry and commerce represent other points of view. And there's pulling and tugging in the White House."

Both Greenwood and Gluck argue that environmentalists didn't fully realize what an advocate they had in Whitman. "I don't think you can fault Gov. Whitman for not bringing strong environmental proposals to the administration," Greenwood said, though clearly she didn't always succeed.

Most recently, Whitman expressed frustration about an Office of Management and Budget analysis that factored the worth of the life of a person older than 70 at $2.3 million while those younger than 70 were assessed to be worth more -- $3.7 million. While supporters of the move argued that it was practical and a realistic way to gauge the effectiveness of regulations, critics saw the change in policy as discriminatory and a way for the administration to undervalue the importance of human life. Whitman initially defended the OMB figures, saying critics were unfairly characterizing them, but after touring the country earlier this month she was frequently accosted by angry environmentalists and senior citizens over the issue. On May 7 in Baltimore, Whitman abruptly announced that the policy had "been discontinued. EPA will not -- I repeat, not -- use an age-adjusted analysis in decision making."

According to the Associated Press, possible successors to Whitman include David Struhs, Florida Department of Environmental Protection secretary, and Josephine Cooper, president of the Alliance of Automobile Manufacturers.

Greenwood expressed the desire that in replacing Whitman the Bush administration "make a selection that will send a positive message to the environmental community." This isn't just for policy reasons; the environment is one of the few areas of vulnerability for the Bush administration and the GOP. In a January Gallup poll, 56 percent of those polled favored Democrats to deal with the environment as opposed to 27 percent favoring Republicans. Not incidentally, GOP pollster Frank Luntz -- in a memo obtained and released by the liberal Environmental Working Group -- issued a warning. "The environment is probably the single issue on which Republicans in general -- and President Bush in particular -- are most vulnerable," he wrote, and as a result Republicans "risk losing the swing vote ... [and] our suburban female base could abandon us."

Through much of Whitman's tenure, however, this was never a pressing concern. As one senior staffer from the Senate's Environment and Public Works Committee assessed, "As long as people are scared of terrorists, most other issues fall by the wayside."

Shares