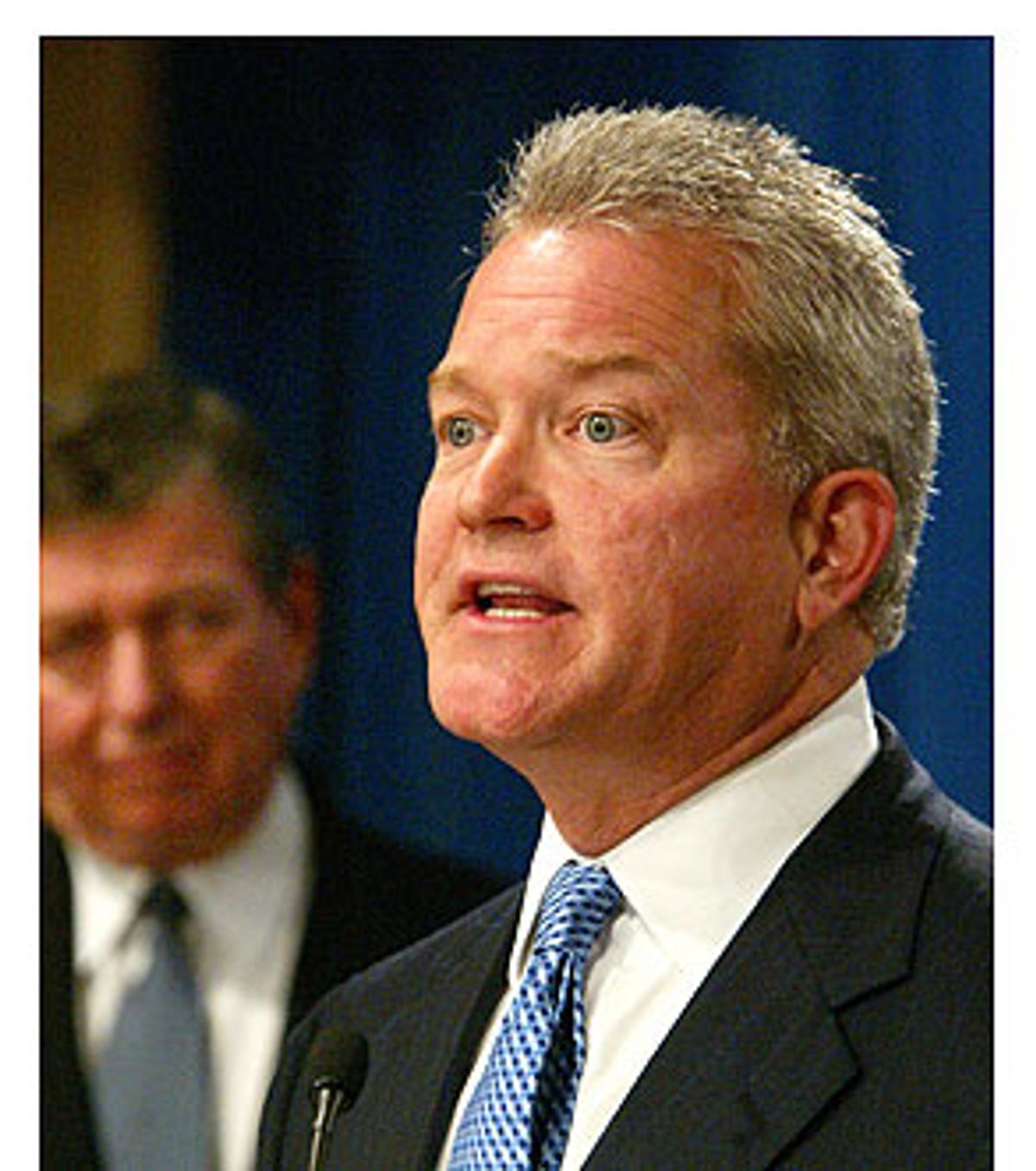

On Thursday afternoon, Rep. Mark Foley, R-Fla. -- a possible candidate for the Senate in 2004 -- held a conference call with a handful of Florida reporters that perfectly captured a dilemma in which he finds himself. The subject of the call was the same matter that he refused to directly address within the call, and it is the one that has quietly dogged him for years: Is he, or is he not, a heterosexual?

Foley, according to a source familiar with the conference call, told reporters that he was hosting the call because he'd heard that one of the biggest newspapers in his district -- the Fort Lauderdale Sun-Sentinel, whose reporters were not invited on the call -- planned on being the first newspaper in the "mainstream" press to write about his sexual orientation, following on the heels of some alternative newspapers that had raised the issue. Some things -- like a politician's religious affiliation -- are for public consumption even though there are people who don't think they should be, said Foley, a 48-year-old bachelor. But some things just aren't for public consumption, he said, and with that in mind, Foley declared that he was not going to answer the question as to whether he's gay. People have a right to privacy, he said, and that's his position on the matter and how it will remain throughout his campaign for the Senate.

Until Thursday, Foley had yet to acknowledge these stories publicly; if he had his druthers, they would all just go away. Maybe they will. But the matter raises a provocative question: How much do we really have a right to know about our elected politicians? And it also raises inevitable questions about Foley's own party. If Foley continues to ignore the question, there will be plenty of people who will assume he is simply hiding his homosexuality. And for a Republican Party stigmatized in recent months by comments widely perceived as anti-gay by its No. 3 man in the Senate, it raises the question of whether Foley believes his party faithful, among others, will reject him if he reveals his sexuality.

Foley's office noted that myriad Republican officials were issuing statements on his behalf. The one issued by Majority Whip Roy Blunt, R-Mo., states: "Mark is one of my Deputy Whips. He is a key part of virtually every bit of work that we get done up here. He is an integral part of our team, and I value his help, advice, and understanding of what needs to be done and how to get it done."

Presumably Blunt is reading from the textbook of those, like Charles Francis, a friend of President George W. Bush and co-chair of the influential Republican Unity Coalition, who think that Foley's answer is totally acceptable and should be left right there. "I believe in the 'non-issue' approach," Francis tells Salon. "Homosexuality as a non-issue is something that Republicans aspire to, it's the president's worldview, and it's something I've tried to create at the Republican Unity Coalition." Foley's non-answer to the question would seem to fit in with the non-issue theory. "He has the right to say what he wants about his private life as he faces the voters," Francis says. "God bless him, and good luck."

Another prominent gay Republican organization agrees. "Our position is that our first priority is turning what is now a Democratic seat in the Senate to the Republican side," says Patrick Guerriero, executive director of the Log Cabin Republicans. "We're less concerned with any of the candidates' sexual orientation than where they stand on issues of fairness." Guerriero noted that Foley's probable GOP primary opponent, conservative former Rep. Bill McCollum, sponsored a hate-crimes bill that offered protection to gays and lesbians, "so we have two candidates who have some track record on being right on our issues."

He issues a warning to Democrats looking to exploit Foley's discomfort. "I hope we're not coming to a time when every single candidate will be asked to tell every single thing about their personal life," he says. "The Democrats should know that this would be walking down a very dangerous path." After all, as another Republican activist points out, there are plenty of rumors about the sexuality of a current Democratic senator and two Clinton administration Cabinet officials. People in glass houses (however divinely decorated)...

Even some partisan Democrats agree. "I think he has a right to take" the position of not answering the question, says openly gay Rep. Barney Frank, D-Mass. "I used to take that position 17 years ago." Careful to not address the issue of Foley's sexuality one way or another, Frank says he disagrees with gays who refuse to acknowledge their sexuality. "While I do think you have right to keep things private, when you do that, it leaves an implication that there's something wrong with it."

And at least one veteran of the Clinton era, epitomized by what he called the "politics of personal destruction," feels Foley will be facing this question for as long as he pursues the Senate seat. "Anybody, whether they're gay or straight, they have a right to their own sex life," says James Carville, a former Clinton campaign official and now co-host of CNN's "Crossfire." "But I doubt there's much he can do to stop this. He can have all the conference calls he wants."

And liberals will be the least of Foley's worries. Lori Waters, executive director of the conservative Eagle Forum, tells Salon that what matters most to her organization "is how he votes, and he is not a conservative. If he's out there pushing the gay agenda, we're very much opposed to those things, and I would hope the voters in Florida would be as well." But even a candidate with a strong record on the issues that Eagle Forum cares about -- Foley scored 65 percent on its 2002 voting chart -- couldn't assume Eagle Forum support if he or she is gay.

"We certainly don't agree with the gay lifestyle," Waters says, "and when it comes to our decison-making for the PAC as to who we support, we have to give to people who are consistent with the values of those people who give to us." If a conservative candidate were gay, "that would be a real stumbling block," she says.

Even some of those who support Foley's right to privacy see situations in which he might have trouble continuing his refusal to answer the question. Frank says that Foley will be trying to join the U.S. Senate, "a body in which Rick Santorum is the third-ranking member. So it's not entirely irrelevant." Last month Santorum, R-Pa., gave an interview to the Associated Press in which he likened the legality of homosexuality to that of bigamy, incest and bestiality. If a GOP senator is elected from Florida in November 2004 -- Sen. Bob Graham, D-Fla., is currently running for president and may or may not seek reelection -- that individual will cast a vote either for or against Santorum, now the chairman of the Senate GOP Conference and a possible future candidate for Senate Majority Leader.

Francis allows that asking how Foley would vote on Santorum's anticipated leadership races would be a fair question, as would Foley's thoughts on Santorum's remarks -- which he has yet to make public. And that seems to be the problem: That line of questioning leads directly to logical questions about how Foley feels about a man who thinks that gay relationships have no more legal basis than incestuous ones, and no more right to acceptance in society than what Santorum called "man on dog." And that leads to perfectly reasonable questions about why he personally feels that way.

Moreover, in a political primary -- especially a Republican one where Christian conservatives make up much of the base, not to mention one in a Southern state like Florida -- whispers that Foley is gay, regardless of their accuracy, will likely have an effect on the race.

Carville, who hails from Louisiana, argues that there's no way to know how such a matter will factor into the election. "There are very few acknowledged gays who have run in Republican primaries in the South, so you don't really know," he says. "I mean, you can't go to a racing form and see what they traditionally do. My guess is it's not going to be terribly helpful."

Many of Foley's likely voters, Carville says, consider homosexuality "a sin and an abomination against nature." If some religious voters look at homosexuality as "immoral conduct that cannot be tolerated," Carville doesn't see how they could just brush the matter off, as Foley seems to hope they will do. "He goes and campaigns in some of these fundamentalist churches where they are, if I thought it was a sin and an abomination, I'd ask him, right there, 'Are you a sodomite?'"

If a candidate tried to evade questions about whether he attends meetings of the Ku Klux Klan, Carville says, "it wouldn't be enough to say, I'm not going to answer that. You'd have to answer that before I'd vote for you. And a lot of fundamentalist Christians view homosexuality the way I view the Klan."

These issues are what prompted the April 26 Sun-Sentinel column by Buddy Nevins, which artfully tap-danced around the issue by focusing on how Foley's liberal bent on issues of gay and lesbian rights -- in 2000, he merited a 100 percent rating by the Human Rights Campaign, which bills itself as the nation's leading "lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender equal rights" organization -- seemed incongruous with his conservatism on other issues. "I believe -- as a longtime political writer and columnist in the state of Florida for over 20 years -- that this will affect his campaign," Nevins tells Salon. "We will continue to look at this subject and follow it."

Nevins broached the matter with the congressman of how those votes might hurt him in a GOP primary, and says he took note of Foley's discomfort in discussing the matter. Foley is "clearly uncomfortable talking about gay rights in this campaign," Nevins wrote. "His speech slowed and his face darkened when asked a question about it." Foley told Nevins that he hoped "people would understand that those votes are fairness issues -- nondiscrimination against employees and things like that."

Following that story came a May 8 cover story in an area alternative weekly, the New Times of Broward-Palm Beach, titled "Out With the Truth: With His Voting Record at Issue, Why Won't U.S. Congressman Mark Foley Just Say That He's Gay?" That story prompted a May 22 cover story in the Washington Blade, a gay and lesbian newspaper in D.C. "Newspaper Outs Fla. Congressman," read the Blade's headline. "Republican Mark Foley's Staff Says Sexual Orientation Irrelevant to Senate Bid."

Throughout it all, Foley remained mum. "Frankly, I don't think what kind of personal relationships I have in my private life is of any relevance to anyone else," Foley said in 1996 when the Advocate claimed he was gay in a story about the Defense of Marriage Act, legislation against the federal recognition of gay and lesbian marriage. Foley, along with most other members of Congress and President Clinton, supported the legislation. "I know one thing for certain: When I travel around the district every weekend, the people who attend my town meetings and stop me on the street corner certainly are a lot more concerned with issues like how I voted on welfare reform or whether or not Medicare is going to be there when they need it -- not the details of whom I choose to have a relationship with."

The only time Foley seemed to answer the question came back in 1994, when he first ran for Congress. When asked about his sexuality by his hometown newspaper, the Stuart (Fla.) News, Foley responded: "I like women."

Guerriero of the Log Cabin Republicans says Foley's record should suffice. "Mark Foley's record on matters of fairness to all Americans of all walks of life is clear and unequivocal and makes it clear he does not concur with the sentiments expressed by Sen. Santorum," he says. "While we welcome Republicans and Democrats to speak out against Santorum's comments, which were so hurtful to some members of our American family, we're far more interested in the comprehensive nature of their public service."

Towson Fraser, communications director for the Florida Republican Party, agrees that Foley should be judged on his record and nothing else. He acknowledges that the recent stories have not escaped notice down in Tallahassee but refuses to touch them. "From our standpoint," Fraser says, "Congressman Foley is a valued member of our Republican family. He has a strong conservative record of supporting the president, and we're not going to get into that kind of gossip and innuendo." Won't Foley have to address the question? "That's a question for him," Fraser says. "We're not going to allow our primary and eventually the U.S. Senate race to degenerate into a contest of nasty rumors and gossip."

But privately, many Republican officials acknowledge that Foley will sooner or later have to address the matter -- and they hope it will be sooner. Many consider Foley to be a strong and appealing candidate who could run a strong race, though they acknowledge that if he's gay, that could hurt him in some more conservative areas of the state, particularly if the Democratic party nominates a moderate-to-conservative candidate.

What of the inevitable questions that will come from Democratic attack dogs regarding what they would characterize as the intrusive nature of Independent Counsel Kenneth Starr's investigation and the impeachment proceedings against President Clinton? Foley, after all, voted in favor of two of the four articles of impeachment.

"It's apples and oranges," says Francis. "Monica Lewinsky was a private affair gone public." Guerriero agrees, saying that while there was "overkill," "the president brought that scandal upon himself and brought it into the Oval Office."

Carville says he doesn't think Foley's role in Clinton's impeachment should have any bearing one way or another, but that the Santorum questions seem a more convincing way that this could become an issue in his race.

Frank, the Massachusetts representative, points to three recent races where gay Republican candidates were defeated in primaries and says that, though Foley's non-answer might work, he doubts it will. "I would think his dilemma is in part because he thinks if people think he's gay -- and I've carefully not commented on whether he is or he isn't -- they would hold it against him," Frank says. "Some of the right-wingers, however, seem to accept gay candidates as long as they seem kind of abashed by it."

Gay Republicans appealing to conservative voters may take solace that some "seem to accept the fact that being gay is beyond their control," though they "wouldn't accept someone acknowledging being gay if he appears to be unashamed of it," Frank says. Thus, a gay Republican might be OK not denying that he's gay, the congressman says, "as long as he appears to not be happy about it."

Shares