Squeezed between Jefferson Davis’ neoclassical Confederate White House and the Medical College of Virginia is a modern 1970s-era building. It is largely plain but for the banners that flank the entrance: the city flag of Richmond, Va., the state flag of Virginia, three Confederate nation flags and the quintessential Confederate flag, the Southern Cross. This is the Museum of the Confederacy, and it is the last banner, in particular, that marks the site as a flashpoint in American culture.

For years, the museum has been trying to find a comfortable position on the Civil War, one that principally would be inoffensive, one that acknowledged a shortsightedness in the South’s position without alienating the hard-core partisans of the Old South who have regarded the museum and Davis’ home as shrines to good days gone by. But in recent months there’s been a shift. A new administration planted the Southern Cross out front, and this month the museum opened a new exhibit that is already arousing volatile passions.

It’s a complex exhibit and one that does not gloss over the existence of slavery. But its underlying narrative on that disgraced institution is simple: Yes, many slaves opposed slavery and fled North at the first chance, but other slaves, whose voices have been lost to history, did not. They included “some black Confederates, and not just slave laborers, but men who actually through their own free will supported the Confederate cause,” says John Coski, the museum’s historian.

It is the kind of observation certain to leave many people incredulous. Among them is former Gov. Doug Wilder, a Democrat who at 71 is old enough to be the grandson of slaves. When Wilder hears such sentiments — and they are not entirely rare in modern Richmond, the capital of the Old South — it reinforces his conviction that Virginia, and the entire nation, need a museum of American slavery to fully comprehend the institution’s complexities.

“Let me tell you something,” he says in a low, steady voice. “When Grant was coming toward Richmond, they [the slaves] were told that the Northerners were going to kill them all — masters and everyone else. My grandfather became so frightened that he hid in a silo and almost suffocated to death. He was rescued by Northern troops. My point is that for them to put that on display now is counterproductive and it will hurt any reconciliation … That’s why it’s so necessary for the slavery museum to exist. To tell it as it is, unbiased.”

Wilder’s idea, somewhere between a dream and a firm plan at this point, is to help resolve the still open wounds of slavery by confronting them head-on and at a $200 million National Slavery Museum on the banks of the Rappahannock River in Fredericksburg, Va. Sitting in his office at the Virginia Commonwealth University in Richmond, where he’s a professor of public policy, Wilder talks about how he believes such a museum will do more than preserve the artifacts of the slave trade. It will show the grim facts of how slavery shaped the nation — and how it haunts the American dream.

“The slavery museum, in brief, should be able to cause people to reassess their attitudes about human beings, particularly about human beings of color,” Wilder says. “If it does not, then perhaps nothing will.”

One hundred and 40 years after President Abraham Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation, the United States, and the South in particular, still struggle with slavery’s vestiges. Late last year, Mississippi Republican Trent Lott was forced to step down from his post as Senate majority leader after making remarks perceived as wistful for the days of racial segregation. Georgia’s new governor, Republican Sonny Perdue, was tripped up this spring by his 2002 campaign promise to bring back the state’s former flag, which from 1956 until 2001 incorporated the Confederate battle emblem. In the end, Perdue reached a compromise with state legislators and agreed to let voters decide next year whether to keep the current flag or adopt a new one based on the Confederate “Stars and Bars” with the added motto In God We Trust. And last month, there were heated protests in Richmond over placing a statue of Lincoln and Lincoln’s son Tad at Richmond’s historic Tredegar Iron Works, where cannons for the Confederate Army were forged.

All these incidents tell a part of the same troubling story: The Civil War has long been over, but even now slavery remains a ghost that time alone has not banished from the American conscience.

Wilder recognizes some Americans may not want to unearth slavery’s past. The sad truth is that the United States, to a large extent, was built by slave labor and its history as a nation was shaped by slavery. A convincing case can be made that, if not for slavery, the U.S. might not be the world power it is today. In that sense, slavery has indisputably shaped and influenced every American’s life. Yet, because it affronts our sense of our country’s idealistic precepts that “all men are created equal,” and because it creates in both blacks and whites a deep sense of shame, we’re reluctant to talk about it, let alone build a museum that commemorates the enslavement of other human beings.

Wilder envisions his National Slavery Museum examining, as he puts it, “the roots and fruits” of the slave culture, from its beginnings in the late 15th century off the African coast through modern times. It will show the history of the African slave trade, where tribes sold other tribes to European traders, but also educate visitors about the slaves’ lives: their origins, their languages, their religions, their customs, as well as their contributions to American life. Wilder sees the museum as an educational center, complete with an auditorium, lecture halls, research offices, a library, exhibition space, a repository for artifacts and documents, a full-scale reproduction of a slave ship, and a bookstore. He envisions millions of tourists to Virginia and Washington making the detour to Fredericksburg.

However harmless Wilder’s effort seems in the early 21st century, it is sure to provoke renewed controversy over the Civil War — and slavery’s legacy — in a place where the dominant culture views the past through a lens of romance and denial. There’s no dispute that slavery is a part of the history of the North and the South. But slavery cannot be discussed without delving into the antebellum South’s role in perpetuating and expanding it westward, and the Confederacy’s stalwart defense of it.

For some Southerners, especially the Sons of Confederate Veterans, whose modest membership of 35,000 belies its formidable political clout, that’s simply not acceptable.

“If Douglas Wilder plans on telling the whole story of slavery, then it’ll be good,” says Bragdon “Brag” Bowling, commander of the Virginia division of the Sons of Confederate Veterans. “If not, it’ll be more of the same: trying to demonize Southerners and leaving out Northern shipping merchants and the blacks who turned over other tribes to the Dutch and the English slaver traders. I’m concerned that the Southerner will be the bad guy in this and it was a whole lot more than that.”

In some respects, it is remarkable that the United States doesn’t have a museum dedicated to slavery, an institution that endured close to 250 years in this country. The first African slaves arrived in Jamestown, Va., in 1619, a year before the pilgrims landed at Plymouth. By the time of the Civil War in 1861, there were roughly 31.4 million Americans and 4.4 million of them, or 14 percent, were African-Americans. Of those, 4 million were slaves in the South. Almost one-third of all Southern families owned slaves.

The first national African-American memorial was proposed in 1915, 52 years after Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation freeing the slaves. A group of aging black Civil War veterans pushed for a “Negro Memorial” to commemorate African-American contributions. In 1929, Congress authorized a museum to be built in the capital. Intended to be a neo-classical edifice, similar to the U.S. Supreme Court, the memorial was never to be. That same year the stock market crashed, ushering in the Great Depression, so plans were scuttled. By the time World War II ended, the museum had been forgotten, and more than half a century would pass before Congress seriously considered it again.

In January, Rep. Cliff Stearns, R-Fla., reintroduced a bill to build a slavery memorial in Washington. It has since been referred to the House Committee on Resources. Slavery, says Wilder, is “the untold history of America.” But while he waits to build his museum, slavery’s story in the United States is already being told — in a way that he and many other Americans would hardly recognize.

The Museum of the Confederacy was founded in 1890 by a group of Richmond society ladies who wanted to preserve Confederate President Jefferson Davis’ house as well as enshrine Confederate artifacts and records. The Sons of Confederate Veterans group was founded six years later, and today sees as its mission “the vindication of the Cause for which we fought.” The group’s Web site proclaims Confederate soldiers fought for “the preservation of liberty and freedom” and “personified the best qualities of America.”

When Col. J.A. Barton Campbell, a retired Army Reserve colonel and a member of the Sons of the Confederate Veterans, became the museum’s director in February 2002, one of his first acts was to place the Confederate battle emblem alongside the other flags in front of the museum. He also cut the staff by 20 percent, and soon afterward former museum employees were quoted anonymously in the Richmond Times-Dispatch saying they feared flying the rebel flag was a sign that the museum would begin to embrace a more pro-Southern stance on the War Between the States.

If true, it will mark a dramatic change. Over the last four decades, the Museum of the Confederacy has tried to transform itself from a memorial to the Confederacy to a more mainstream museum of Confederate history. It hasn’t been an easy, or entirely successful, evolution. Even in the late 1980s, at the same time Wilder was running for governor, the museum still told the story of slavery from a distinctly Confederate point of view. At the entrance of the main exhibit, a plaque explained that some Southerners referred to the Civil War as the War of Northern Aggression, a conflict between the Jeffersonian, agrarian ideals of the South and the industrial interests of the North. What scant discussion there was of slavery and its role in Southern life was presented in the best possible light.

One display showed a worn cat-o’-nine-tails with the explanation that although some slave owners whipped their slaves with such devices, most were kind. Displaying that one slave whip outraged unreconstructed Southerners and, of course, the Sons of Confederate Veterans. The rest of the world may be anti-Confederate, they contend, but their museum should provide an untarnished image of the proud and honorable Confederacy. And slavery, especially when slaves are being beaten, ruins that portrayal.

The Sons of the Confederate Veterans were up in arms again a few years later, in 1991, when the museum, with a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities, presented a vast show on slavery, “Before Freedom Came,” with artifacts and documents from roughly 90 private and public collections. By examining slavery, critics thought the museum had — once again — betrayed its Confederate heritage. That’s why they welcomed Campbell’s decision to fly the Confederate battle flag: Maybe the museum was finally getting back to its roots.

“If the museum can’t present a good presentation of the Confederate States of the America, who can?” Bowling asks. “That’s what they’re there for.”

On a bright day earlier this year, posters for the upcoming Civil War movie, “Gods and Generals” hung near the museum’s entrance. The movie, starring Robert Duvall as Gen. Robert E. Lee and featuring a cameo appearance by Ted Turner as a rebel soldier, depicts the early years of the Civil War — from the Southern perspective. Indeed, “Gods and Generals” used 7,500 Civil War re-enactors, who supplied their own period uniforms and weapons, for the battle scenes. In a review, the New York Times said the three-and-a-half-hour movie “goes out of its way to follow the example of ‘Gone With the Wind’ in sanitizing the South’s treatment of African Americans. Its one-sided vision shows freed and about-to-be-freed slaves cleaving to their benign white masters and loyally serving the Confederate Army.”

With such a wistful vision of the Civil War and slavery, “Gods and Generals” could fit unobtrusively into the museum’s current presentations. The museum’s main exhibit is called “The Confederate Years: The Southern Military in the Civil War,” and it doesn’t shirk from discussing slavery’s role in the South’s war effort. But the perspective is decidedly Confederate: Even the brief overview of the reasons for the South’s secession from the Union, at the beginning exhibit, presents the Civil War as more of a disagreement over states’ rights than as an ideological difference over the institution of owning human beings.

“Lincoln’s Republican Party,” it says, “opposed the expansion of slavery and the enforcement of the Constitutional requirement to return slaves to their owners.” And that, it goes on to say, was “an act hostile to the South’s interests.”

Step around the corner and the exhibit goes on to give a fairly rousing justification for why Southerners eagerly donned gray uniforms, drawing parallels with the revolutionary American colonists taking up arms against the British. “Confederate soldiers were fighting a ‘Second American Revolution’ for the rights and liberties that their forefathers had won in the first American Revolution,” says one placard. “Among these rights was the right to own slaves, a right sanctioned by the Constitution and by custom — even though the vast majority of the Confederate soldiers did not own slaves.”

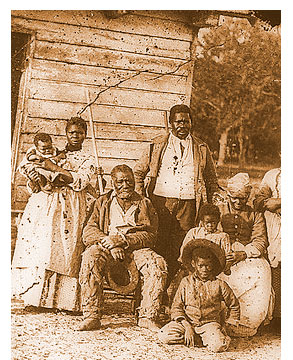

The exhibit also talks about how the Confederate military enlisted African-Americans to build fortifications and serve the army. While it mentions that many Southern states and the Confederate government forced blacks — slave and free — into the military, it also highlights African-Americans who were loyal to the Confederacy. It talks about free blacks in the South forming militias to aid the Confederate cause. (Their offer was refused.) And it looks at slaves who stood by their masters. One such faithful slave was Marlboro Jones, owned by Capt. Randal F. Jones. Under his portrait, a description tells how Jones brought his master home to Savannah after he was mortally wounded on the battlefield. A visitor is left with the impression that African-Americans weren’t all that dissatisfied with slavery. The museum’s newest exhibit, “The Confederate Nation,” will probably not discourage that perception.

Coski, the museum’s historian, is proud that the new show does not depict slavery in stereotypical terms. “African-Americans would be loath to admit that any slave would be loyal to the Confederates,” he says. “And the Sons of the Confederate Veterans and activists would swear up and down that the absence of any slave rebellion shows that slaves were fundamentally loyal to the South.”

The truth, Coski says, lies somewhere in the middle. Though there were no slave uprisings in the South during the Civil War, he points out that about 500,000 African-Americans out of a total of 4 million fled north of the Mason-Dixon line, representing the largest migration in U.S. history. Obviously, he says, that debunks the Confederate myth that content slaves supported the Confederacy. “Hundreds of thousands didn’t act as loyal to the homeland,” Coski says. “They took the first opportunity to go to the North.”

On the other hand, the exhibit will display artifacts and documents showing some African-Americans, slaves and freemen, did indeed back the Confederacy. “It would be illogical and downright patronizing to think that 4 million African-Americans all reacted and behaved in the same way to something like the Civil War,” Coski says. “We will also have artifacts that speak to the stereotypical slaves that buried the silver or protected the master and mistress from the Union Army.”

Wilder himself wouldn’t recognize the need for a slavery museum until 1992, when, as Virginia’s governor — and the first elected black governor in U.S. history — he led a state trade mission to Africa and visited Goree Island, off the coast of Senegal in West Africa. Goree was a central trading post for the early slave trade. Untold millions of Africans passed through island’s so-called Door of No Return. While no hard numbers exist, it’s estimated that traders shipped between 10 million and 28 million Africans overseas. Packed tight in ships with little food and water, more than 2 million of them are thought to have died during the crossing known as the Middle Passage on their way to the Americas and the Caribbean. Wilder’s trip to Goree carried great symbolic significance and a deep personal resonance. After leaving the dark, oppressive museum angry and dejected, he was determined to have America confront its own slave past.

Today, the benign depictions of slavery and “happy slaves” like the one at the Museum of the Confederacy reaffirm his belief that a museum solely devoted to slavery must be built in this country. True, slavery has been abolished in the United States for almost 138 years (slaves in Texas finally heard they were free on June 19, 1865), but it had flourished for nearly 250 years before that. It fueled the U.S. economy and shaped its political discourse. It was the single greatest affront to the ideals articulated at the nation’s founding, and it remains a source of profound conflict and alienation in a racially mixed society. Few people, he insists, understand the degree to which slavery and its aftermath still cast a shadow over American culture.

And yet, where African nations such as Senegal and Ghana, and even the small Caribbean island, Curaçao, have slave museums, the United States does not. This country has a national museum on the Washington Mall to commemorate the Holocaust, a profound global tragedy, but one that occurred in Europe.

To Wilder, it’s striking that it seems easier for Americans to confront the shameful history of Nazi-sponsored genocide. “None of it ever happened here, none of it,” he says. “To the extent that Jews were persecuted here, they were persecuted along with African-Americans. There was anti-Semitism, anti-black, anti-Catholic, anti-anything in terms of people who weren’t the true bloods. I want to show that there aren’t any true bloods in America. I don’t want to talk about what was good and what was bad and who was right and who was wrong. I want to lay out the facts, so you can tell the story for yourself.”

Wilder hasn’t been the only one to contemplate a museum devoted to slavery themes. The National Underground Railroad Freedom Center in Cincinnati, set to open in 2004, will tell the story of roughly 100,000 slaves who escaped from the South in the 1800s, aided by abolitionists who spirited them from one safe house to another, until they were in the North.

And for almost a year, a presidential commission has been looking into building a National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington. President George W. Bush signed legislation in December 2001 to appropriate $2 million for a commission to study the idea. After a series of town meetings around the country, the panel delivered a 122-page report to Congress on April 1, calling for a museum to be built next to the reflecting pool in front of the Capitol. Inevitably, slavery would be a major theme for that museum, says George McDonald, the commission’s director and its liaison with Department of the Interior’s National Parks Service.

“Slavery was the American Holocaust,” McDonald says. “That’s just my own opinion and it needs to be shown in that light. It will show the comprehensive human tragedy. From the Middle Passage where Africans were brought over here on top of each other to when they came here to be branded. We will deal with the whole. But we will deal with slavery in the true form. It won’t be sugarcoated.”

McDonald would like to get initial funding of $45 million for the museum in the 2004 federal budget. The total cost is expected to reach $400 million. With half that amount expected to come from a federal government already contending with the unknown costs of rebuilding Iraq as well as with soaring budget deficits, the project faces long odds in the near term. Yet, Claudine Brown, co-chair of the commission, insists that budget constraints shouldn’t deter federal officials. Congress “has exercised its will to create several other museums in the nation’s capital, whether there were wars, or pestilence, or seven-year locusts,” she says. “There is no viable reason why this museum should not be authorized. I think we have waited much too long.”

Wilder, meanwhile, staunchly believes that the country needs a museum dedicated to slavery — and only slavery. “Slavery is just so big,” Wilder says. “It’s too big to be compartmentalized. It’s the untold story of America: slavery. If you know where it’s been told, tell me.”

It’s been more than a decade since Wilder first proposed building a museum and it’ll be another four years before he expects to have it completed in 2007. One reason it has taken him so long to get his museum off the ground is that he’s been extremely careful in choosing the site. It had to be in Virginia. This is where slavery began in 1619, in Jamestown; it’s where Thomas Jefferson lived, he who owned slaves and yet penned the words “all men are created equal” in the Declaration of Independence; where Wilder’s ancestors were kept as slaves; where major, and bloody, battles of the Civil War were fought; where capital of the Confederacy was located; and where Lee surrendered to Gen. Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox on April 9, 1865. Virginia marks slavery’s beginning in this country and its end.

After returning from his Africa trip in 1992, Wilder spent the next 10 years searching for a suitable location here. Before he started raising money from corporations and individuals, recruiting curators and museum experts, and collecting artifacts and records from private owners and other institutions, Wilder wanted land. As a seasoned politician who never lost an election in almost a quarter of a century, he saw securing the property as a way to retain control over the museum’s creation and therefore, a way to ensure its eventual success. Worried that internal squabbling would derail the project, Wilder wanted to limit the number of people involved early on.

“One of the things I’ve tried to do is keep things tight, so we don’t have political infighting,” he explains. “That comes, trust me, that comes with growth of anything … You have to understand the infighting. There’s so much of it. God have mercy. Who’s going to run this? Why should they run that?”

Jamestown was Wilder’s first choice. But after five years negotiating with the land’s owners, a fundamentalist Christian Pentecostal church, he gave up. (Church leaders were dead set against any tobacco or alcohol on the property, even at receptions and parties.) After his search in Richmond led down a few other dead ends, Larry Silver, a commercial developer and a longtime friend, offered him land in Fredericksburg, about 50 miles from Washington and 50 miles from Richmond. As soon as Wilder saw Silver’s parcel, he knew it was the right spot.

Almost 39 acres, the undeveloped wooded site is on a bluff overlooking the Rappahannock River near I-95. Last year, Silver deeded the landwith an estimated value of $20 million to $30 million — to the National Slavery Museum. When completed, the museum will be part of Silver’s larger 2,400-acre development, Celebrate Virginia, which will encompass stores, corporate offices and three golf courses.

Some local critics have questioned the propriety of placing a museum so near commercial property, but Wilder dismisses those concerns. There is enough land to separate it from the stores and offices, he says. Now, with the land secured, Wilder is turning his attention to planning and building the museum. He estimates it will cost $200 million to complete, but he expects it to be built in stages, as funds are available. So far, the National Slavery Museum has $1 million from Fredericksburg and another $1 million from the state. By year’s end, Wilder wants the board to have a plan in place to raise funds from corporate and individual donors.

That campaign may be a challenge, especially in the current economy. But he and others are optimistic. From planning to its opening in 1993, it took 15 years for the Holocaust Museum to be built. Congress authorized the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum for the American Indian in 1989. That museum’s new building on the Capitol Mall won’t open until September 2004 — again, 15 years later.

In Cincinnati, the Underground Railroad Freedom Center formed in 1994 and began fundraising in the fall of 1999. It has received $91 million in pledges toward its $110 million goal, and expects to open in 2004. Sixty percent of the funds came from individual and corporate donors. Given that the center was able to raise its funding in a relatively small amount of time, Ernest Britton, the center’s spokesman, says Wilder may be able to raise the funds necessary to open a portion of his slavery museum within four years.

“Absolutely, it’s possible,” Britton says. “It’s going to be based on the contacts and the relationships that they are able to establish with donors around the country and how concrete their plans are. People want to see something concrete. We didn’t have artifacts, but we had a schematic and conceptual plan.”

Though he doesn’t have much capital, Wilder has already attracted a distinguished architect for the project: Chien Chung Pei, founder of Pei Partnership Architects in New York City and son of the legendary architect I.M. Pei. At his father’s firm, the younger Pei was the designer in charge of the glass pyramid entrance at the Louvre in Paris and the East Wing of the National Gallery in Washington. He has already shown Wilder preliminary renderings for a slavery museum: a modern structure with a glass gallery at the center with rectangular buildings on the sides and elongated terraces. (Wilder rejected another architect’s design that would have had two glass towers — one with gray panes and the other with dark blue — linked together with large symbolic chains.)

“The [slavery] museum is important for this country,” says Pei, who contacted Wilder after reading about his project. “Slavery is a story which should be told, but it’s important that it be told in the right way, told in a way that helps unite our country more so than to divide it. When you hear statements coming out of people like Trent Lott, you realize some people aren’t living in the 20th century, let alone the 21st. There is a deep-seated misunderstanding about a lot of things having to do with race. I think this museum, by educating people, can overcome a lot of misunderstanding and a lot of ignorance. Maybe I’m being too generous, but I think that ignorance plays a big role in that. But I’m just an architect.”

Wilder isn’t discouraged that after 10 years of his quest to build a slavery museum, he has neither committed donors nor a trove of slave artifacts, records and documents. With a scant $2 million and 4o acres of land in hand, he is confident that some portion of the National Slavery Museum will open to the public in four years — in time for the 400-year anniversary of the settlement of Virginia.

“We’re going to build the museum,” he says matter-of-factly. “Nothing is going to stop us.” Wilder firmly believes that if the United States doesn’t confront its history, in its entirety, then it will never live up to its potential. “This is what [Martin Luther] King was saying: America should live up to its precepts,” he says. “The more we learn about slavery, the more we learn that we haven’t lived up to our creed, the more we learn that we fostered a situation that divides and separates, that we have sanctioned a system that discriminates against human beings, that declassifies human beings … The story here is that America was founded on precepts which were never fulfilled. Opportunity, or recognition of these precepts, is ours if we take advantage of it. If we don’t, something obviously will happen to the fabric of our society. Rather than become closer, it’ll unravel. And no one wants that.”