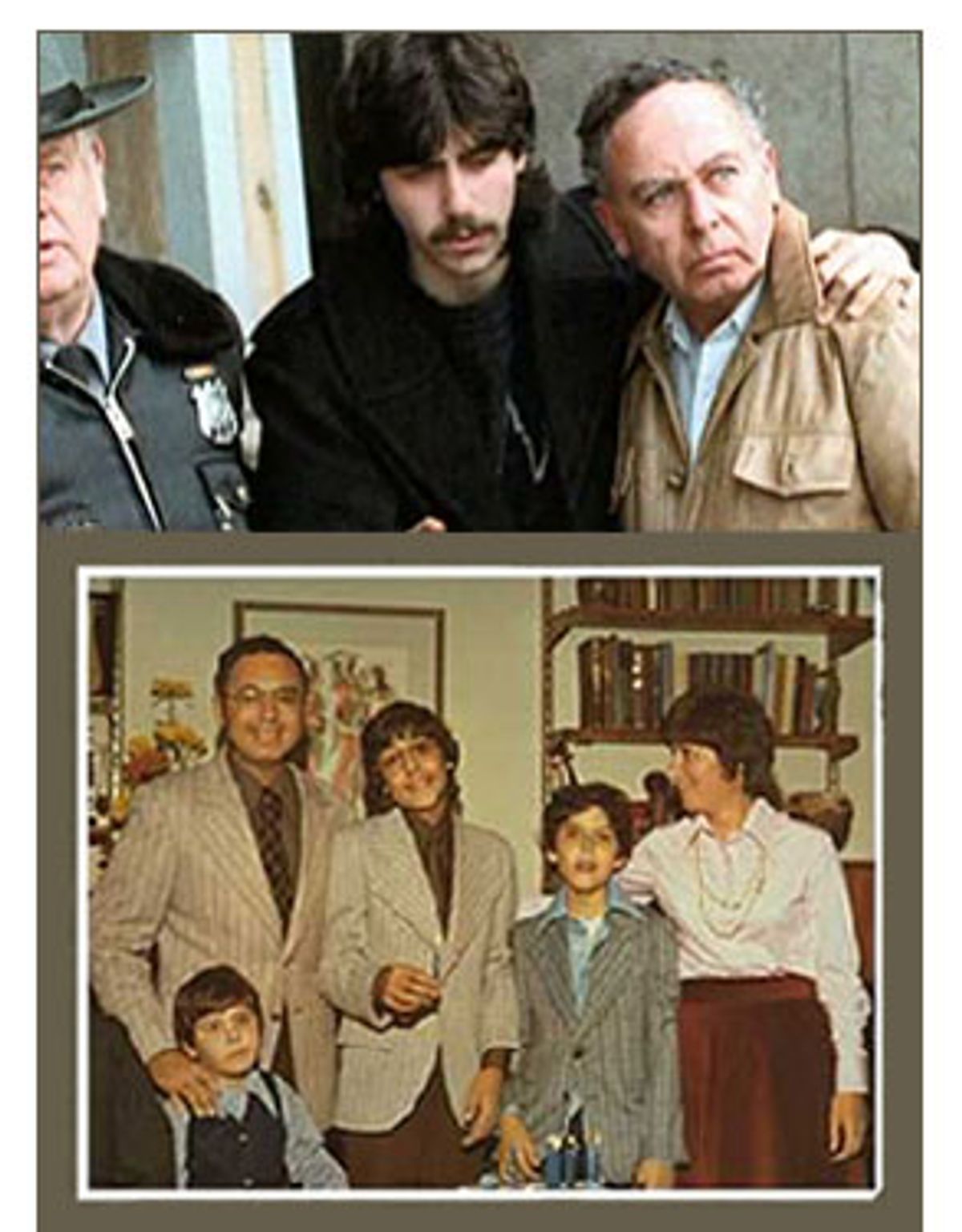

The day before Thanksgiving in 1987, Arnold Friedman, a mild, nebbishy science teacher, and his youngest son, Jesse, were arrested by police at their home in the affluent suburban town of Great Neck, N.Y., and charged with numerous counts of child sexual abuse. As the story unfolded, the cops charged that the father and son had committed their crimes during hour-long computer classes held in the basement of their Great Neck home. Both Arnold and Jesse eventually pleaded guilty. Arnold died in prison in 1995, and Jesse was released in 2001 after serving 13 years of a 16-year sentence.

There was only one problem: They were almost certainly innocent.

It's fitting that the devastating "Capturing the Friedmans," which could be said to be documentary as an act of detection, itself came about through a piece of inadvertent detection. The director, Andrew Jarecki, who had made millions as the founder and CEO of Moviefone, was making a documentary about the people who work as children's birthday party clowns in New York. Nearly everyone he interviewed told him he had to talk to David Friedman, the most successful of the city's party clowns.

In his interviews with Friedman, Jarecki was struck by how bitter this man, who made his living as "Silly Billy," seemed. Pursuing the answer, he eventually found out the history of David's family -- and also uncovered an unlikely treasure trove for a documentary filmmaker. During the trial and up until the time each Friedman began his prison sentence, David had made hours of home movies depicting the family turmoil the ordeal had set off.

"Capturing the Friedmans" includes interviews with David and Jesse (the middle son, Seth, declined to take part in the film) and their mother, Elaine, as well as police, prosecutors, the judge in the case and some of the (now grown) kids who took those computer classes. It also makes liberal use of David's home movies. In other words, the film is not just the history of how a family came apart -- it actually allows us to see the Friedmans coming apart before our eyes.

Jarecki, whose method is sympathetic and nonjudgmental, does not offer any psychological explanations for why David Friedman took those movies (no reason you could come up with would be very attractive). What's important to note is that Jarecki's use of David's home movies rigorously avoids any note of exploitation or prurient interest. In interviews, the director has refused to offer his own opinion on Arnold and Jesse Friedman's guilt or innocence, saying he thinks it's important for each viewer to make up his or her own mind. That's a canny P.R. move -- and also a necessary one. Despite the work journalists have done in discrediting many of the mass child sexual abuse cases of the '80s, despite the jury's wholesale rejection of the charges brought in the McMartin case in Southern California -- the longest and most expensive prosecution in the country's history -- and despite the fact that the FBI never found evidence to support the existence of satanic cults that practiced child abuse and murder, the debate over those cases can still inflame passions. You can hardly blame Jarecki for not wanting potential audiences to expect a jeremiad. And to his credit he hasn't delivered one.

But I don't see how any reasonable person could watch "Capturing the Friedmans" and not see it as a tale of mass hysteria and the American judicial system gone amok. No physical evidence was ever found to corroborate the charges against Arnold and Jesse. The only former student interviewed in the film who still says he was molested later reveals that his memories of abuse only came to light after his parents put him in therapy, where he "recovered" those memories under hypnosis. Another former student, Ron Georgalis, ridicules the stories of abuse and says he never saw anything remotely like them occur. One student who did claim to be molested admits in the film that he made up the stories to escape the pressure the police were putting on him to admit that something happened. (His story alone led to 16 charges against Arnold and Jesse.) And a parent of one of Arnold's computer students tells how, when he determined that nothing untoward had happened to his son, he found himself under pressure from the cops to say that abuse had occurred, and was even attacked by neighbors who told him he was "in denial."

That said, there is a complicating factor in the Friedmans' story, and not an insignificant one: Arnold Friedman was a pedophile. The case against him began building when he was arrested in a postal sting operation for ordering child porn from the Netherlands. A further investigation began when John McDermott, a government postal inspector, noticed the Friedmans' basement set up for computer classes and suspected, as he says in the film, "We could have a problem here." Arnold Friedman later admitted to molesting two boys (neither one of them a computer student) near his family's vacation home, and said that when he was 13 he molested his 8-year-old brother, Howard.

But no victim has ever come forward to verify those claims, and Howard, a gentle man overcome with grief at the destruction of his brother (his interviews with Jarecki are the film's most painful), says he has no memory of sexual abuse. To complicate matters further, Jesse Friedman, at his sentencing, claimed that his father Arnold had molested him when he was a child. In the movie, however, Jesse denies that. He says he told the story at his attorney's urging, in hopes of a lenient sentence. (The lawyer, for his part, believes the story about Arnold having abused Jesse is true.) None of those denials, of course, will carry much weight with proponents of repressed-memory syndrome, who treat every assertion of innocence as further proof that something terrible must have happened

But even if you decide that Arnold Friedman's admissions were something more than a way of expressing guilt for his pedophile urges (which had driven him into therapy), there seems little doubt that the case against him and Jesse was bogus. It isn't just that not all pedophiles act on their urges -- it's the crazy nature of the allegations. If these stories of hour-long computer classes turned into ongoing bacchanals of violent sexual abuse were true, then parents picking up kids afterward would surely have found their children in physical and emotional pain. They would have found blood or semen on their clothes. They certainly wouldn't have reenrolled their kids in Arnold's classes, as many parents did.

No Great Neck parent ever raised an alarm about Arnold Friedman. This fits in with the recurring narratives common to all mass abuse cases -- increasingly elaborate, steadily expanding stories that somehow leave behind no trace of physical evidence. And the interviews with the police and prosecutors in "Capturing the Friedmans" give you a clue as to how these stories developed.

It's a given that cops are usually censorious when it comes to what they consider any unconventional sexual behavior. How many times has the presence of pornography, or evidence of an extramarital affair, been a red flag for all sorts of suspicions? Now imagine how those suspicions increase when there are allegations that kids are being sexually abused. The cops and prosecutors in "Capturing the Friedmans" are frightening because their absolute conviction in the rightness of their suspicions and methods is matched only by their apparent stupidity.

Detective Sgt. Frances Galasso, the retired cop who headed the investigation, says, "Everyone could see what was going on." But none of the stories were ever validated; no one saw anything. At one point, Galasso talks about the Friedman home as a nightmarish den of depravity, with stacks of pornography visible everywhere. As she says this, Jarecki shows police photos taken during the raid on the ordinary suburban home, which show nothing amiss (Arnold's cache of porn was, befitting his shame, hidden away behind the family piano). Later, Lloyd Doppelman, a detective who worked the case with Galasso, talks about how he and other cops went about gathering "evidence." Essentially their method was to tell the kids they knew something had happened and that the kids had better tell the truth. "If you talk to ... children," Doppelman says, "you don't give them an option."

Jarecki allows the cops and prosecutors to hang themselves with their own words. But you wish that his impulse to be fair and nonconfrontational didn't impede him from challenging these people with the ridiculousness of their claims. All the mass child sexual abuse cases, taken together, never turned up any consistent, provable evidence of anything -- except a widespread pattern of police and prosecutorial misconduct. Galasso should have been presented with the photos taken during the raid and asked to point to the alleged piles of pornography. Doppelman should have been asked what the point of gathering evidence is when the cops think they already know what happened and browbeat witnesses into submission to confirm their suspicions.

When the judge who presided over the case, Abbey Bolkan, says, "There was never a doubt in mind as to their guilt," you long to see her made to square that statement with a judge's sworn duty to be impartial. When the assistant district attorney, Joseph Onorato, says, "There's a reasonable human expectation of some people that where there's smoke there's fire," you wish Jarecki had asked him if, absent any physical evidence, this was the assumption on which his office proceeded against Arnold and Jesse Friedman. When cops, a prosecutor and a judge so flagrantly violate the ethics of their respective offices, they deserve to be made to squirm at least a little.

Where Jarecki's determination to be fair does work is in the interviews with Arnold's widow and Jesse's mother, Elaine Friedman. I found it impossible to resolve my feelings about her. It's clear she felt trapped in a rotten marriage with a man who couldn't begin to address her sexual needs. And the confusion and betrayal she feels when deeply troubling charges are brought against her husband and son is understandable. In her way, Elaine Friedman shows a sort of integrity. Because she doesn't know what happened, she refuses to say one way or the other. But there's also something needy and whining about her. At times she seems so focused on her pain that she can scarcely acknowledge the pressure on Arnold and Jesse. Jarecki's movie also makes it seem as if, in part, she persuaded her husband and son to plead guilty for her own peace of mind.

You experience it as a slap in the face when Elaine says that, after her husband and son went to jail and she was alone in the house, she felt peace. It's understandable, given the horrible family arguments David captured on video, that she needed a break. Yet you can't help seeing something selfish in her lukewarm support of her husband and son against what she should have seen were ludicrous and unsubstantiated charges, and you can't help disliking the way she takes her resentment of her husband out on her sons. But the image the film leaves you with -- Elaine reuniting with Jesse on his release from prison -- makes clear how badly she was torn up by what happened.

People who doubt that the Friedmans were entirely innocent of the charges against them will ask, reasonably enough, why they pleaded guilty to such damaging criminal charges. As Jesse says in an interview, there was no way, on the Long Island of 1988, that he could have gotten a fair trial. (He couldn't have gotten a fair trial anywhere else in the United States either.)

At one point we see a clip from a Larry King interview with Debbie Nathan, one of the first journalists to cast doubt on the veracity of the mass child sexual abuse stories. (Her book, "Satan's Silence," co-authored with Michael Snedeker, is the best account of the phenomenon that's yet been written.) King's first question to Nathan sets the tone. "So all these parents are wacko?" he asks. Certainly some of them were. "Satan's Silence" reported that the woman who first made allegations in the McMartin case had a history of paranoid schizophrenia. Nathan is interviewed in the film, mostly about how she became interested in the Friedman case. Jarecki misses the chance to include the larger context Nathan could provide.

For example, Nathan has made the case that it was no accident the legend of mass child sexual abuse caught fire in the '80s. With Reagan in the White House and the country turning to "traditional values," stories of mass child sexual abuse allowed a focus for national anxieties about mothers who worked outside the home and the changing structure of the family. It's one of the horrible ironies of this whole sorry episode that, as they did during the Meese Commission's anti-porn crackdown, right-wing extremists found common cause with some elements of the feminist movement. Using the dubious notion of "repressed memory," some feminist therapists were able to present a romance of children and women as the victims of mass abuse, of fathers who routinely raped their daughters. In a great Orwellian construction, absence of evidence was taken as proof. (The notorious incest-survivor's handbook "The Courage to Heal" told readers that if they thought they might have been abused they probably were, and that questioning whether you had really been abused was "a misguided attempt to repress the memories again.")

One of the main reasons fantasies of mass child sexual abuse took hold -- our national obsession with the purity of children -- isn't limited solely to the '80s. It was often argued that kids couldn't possibly be making up stories like the ludicrous scenarios held up as fact during the worst of the panic. In fact, kids weren't. As the proceedings of many cases showed, the stories were planted by overzealous cops and prosecutors and investigating psychologists. But the larger implication of that defense was the comforting belief that little kids simply do not have sexual thoughts.

A few weeks ago, the New York Times ran a letter from a reader supporting Wal-Mart's decision to ban FHM, Maxim and Stuff magazines from their stores. The correspondent said that the magazines were dangerous because they were on view to adolescents who were "corruptible innocents." You have to be living pretty far inside a fantasyland to believe that adolescents can be corrupted by photos of starlets in bikinis and lingerie. But if that belief in adolescents as "corruptible innocents" has any currency -- and I think it does -- then you can understand why children would be fantasized and fetishized as wholly pure beings. One of the tragedies of the '80s cases, as Nathan has pointed out, and as scholar Frederick Crews pointed out in his 1994 New York Review of Books article debunking repressed-memory syndrome (reprinted in his book "The Memory Wars"), was that these fantastic, delusional stories drew resources and attention away from actual child abuse cases.

In cases like that of the Friedmans, the uncomfortable fact remains that the real victims were most often the accused. Even in a rare case like the McMartin trial, where the jury rejected the prosecution's case, the defendants had become stigmatized. Many more are still in prison on bogus charges. And then there are the accusers, many of them young children who suffered God knows what trauma by being convinced they'd been subjected to unimaginable abuse so they could be used as tools in phony prosecutions. The sole accuser of the Friedmans whom we see, the one who admits he didn't remember anything until he underwent hypnosis, seems to be a basket case. His "recovered" memory alone accounted for 35 charges against the Friedmans.

"Capturing the Friedmans" is a slice of one of the ugliest chapters in American history, one to which the overworked appellation of "witch hunt" can reasonably be applied. Andrew Jarecki could have done more to lay out the marriage of sexual and religious and social hysteria that made cases like this possible. But he deserves credit for having the guts to say, in this case and in so many like it, who suffered the most.

Shares