May Day this year brought revelations about two newsroom scandals involving gross ethical lapses by young reporters. Each meltdown badly injured a newspaper's reputation, but how the top editors responded has marked the difference between one daily recovering its credibility and the other remaining mired in controversy.

On May 1, readers of the New York Times were informed that a young reporter by the name of Jayson Blair had resigned the previous day, after being confronted with proof that he'd blatantly plagiarized material from another newspaper. With more digging, the newspaper uncovered a tomb full of Blair deceptions and lies, as well as an appalling work record, which were soon chronicled in detail inside the Times' pages.

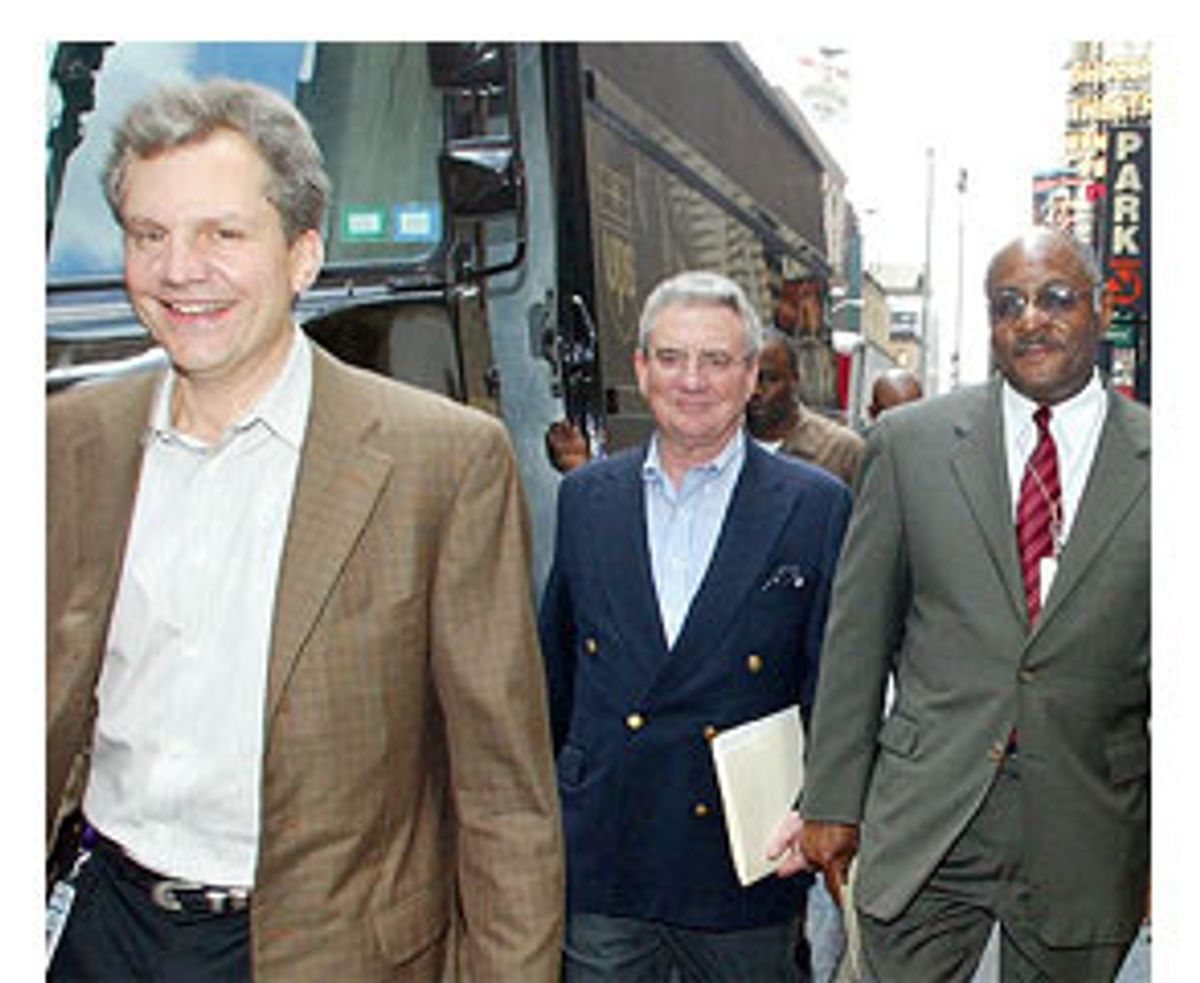

Executive editor Howell Raines took responsibility for the fiasco and vowed to fix what had gone wrong at the Times, but he did not offer to resign. In fact the Times' publisher, Arthur Sulzberger Jr., who hand-picked Raines for the job two years ago and who has been Raines' patron for the past decade, told newspaper staffers gathered at a contentious town hall-style meeting three weeks ago that he wouldn't have accepted Raines' resignation even if it had been offered.

By comparison, readers of the Salt Lake City Tribune opened their paper the same May day to discover the Tribune editor had resigned, the victim of a newsroom scandal involving two young reporters who secretly sold to the National Enquirer salacious, unconfirmed law enforcement rumors about the kidnapping of Elizabeth Smart in 2002. When the editor, James Shelledy, first heard of the charges, he suspended the reporters for two weeks and announced the action in his Sunday column, rather than have the Tribune write a straight news story. (It turned out Shelledy did not have all the facts of the case at the time.)

The mild rebuke caused a newsroom uproar. Days later, with his publisher standing at his side, Shelledy announced his resignation. In a separate letter to the staff, he wrote: "The Tribune hit an iceberg and I was at the helm. For 12 gratifying, exciting years, I have been at the helm of the newsroom. Collisions and damage control were my responsibility. Solely. The buck knew where to stop. And did."

More and more observers, both inside and outside the Times, are wondering if the Times would be better off if Raines offered -- and Sulzberger accepted -- a similar buck-stops-here farewell. While Shelledy's departure effectively marked the end to the Tribune's mini-scandal, more than a month later the Times is still reeling. Rival journalists, perhaps anxious to dent the Times' national standing as the most important daily newspaper in the country, continue to circle the paper looking for fresh evidence of Raines' mismanagement, while an army of angry staffers who feel misused under Raines are grousing openly (if anonymously) about their editor. [Editor's note: On Thursday, Raines and his deputy, Gerald Boyd, resigned.]

Even Raines' supporters concede that the controversy has spread far beyond one discredited reporter. "Jayson Blair was Mrs. O'Leary's cow," says Jim Dwyer, the Pulitzer Prize-winning reporter for the Times, referring to the firestorm that's swept the newsroom in the last month. "His misbehavior, his betrayal, opened up a lot of score settling, not only inside the newspaper but outside as well."

"People outside the paper feel it's a miracle Howell's still editor," says one senior Times staffer. What's the tipping point for the Times? The only person who can answer that is Sulzberger, and he's not talking.

The story began a month ago as an account of Blair's misadventure, and whether Raines, as an avowed Southern liberal, gave the young black reporter too many second chances. The problem now, however, is that the story has been transformed into one about Raines' domineering, often arrogant leadership style and whether he has the ability to remain in the job. "Jayson Blair is forgotten at this point by everybody," notes one staffer.

The bridge that took the narrative from Blair to Raines was constructed last week with the revelation that Pulitzer Prize-winning Times reporter Rick Bragg, a close friend of Raines', had been suspended for not crediting the work that an unpaid intern had done on an article under Bragg's byline. As the story mushroomed, Bragg's response was, essentially, that everyone at the Times does it; when that provoked open revolt among some of his colleagues, Bragg called his good friend Raines and resigned. There's no evidence Raines knew about the corners his friend had cut, but the suspicion inside the newsroom lingered that some members of Raines' star system have been allowed to play by a different, more lenient set of rules.

Under the guidance of Sulzberger -- a fourth-generation Times leader who in 1992 became its publisher at the age of 40, one who emphasized teamwork and a new, Outward Bound brand of cooperation -- the Times has handled the current crisis in an unusually public way. The paper published an exhaustive, 14,000-word package on Blair, held the now infamous town hall meeting in a Broadway theater, and formed committees to sift through the wreckage and make recommendations. Meanwhile, young reporters at the Times have suddenly felt free to band together, air their grievances and demand changes in newsroom policy.

But the new brand of transparent management -- which would have been completely foreign to Sulzberger's father and longtime Times publisher, Arthur "Punch" Sulzberger -- has some inside the paper scratching their heads and wondering if it hasn't done the Times, and especially Raines, extraordinary damage over the last four weeks. "I'm devastated over how this has all been handled," complains one Times veteran. "The Times is saying, in effect, 'I'll bend over and kick me in the ass. And then kick me hard and kick me harder.' It's the Times that's keeping the story alive, and it's done Howell in. He's getting pummeled."

So is the newspaper, and its political rivals are basking in its misery. "You know who's getting the greatest satisfaction of this?" asked one longtime Times newsroom employee. "It's the Christian right. They've been trying to cut the Times' throat for a long time for being a liberal paper."

Meanwhile, the Times' management, anxious to begin its long climb out of an unprecedented hole, is still trying to figure out if the newspaper has hit bottom or if there's more to come. For instance, newsroom rumors were rampant this week that the Wall Street Journal was set to publish yet another damaging story about the Times and raise new questions about newsroom practices under Raines. The central question is whether Raines can survive another misstep.

The turn of events for Raines, considered among the most gifted, and polarizing, editors of his generation, is stunning. "This is a man who was just saluted for having led the Times' coverage of 9/11, which won seven Pulitzer Prize awards, and then it all fell apart," notes one Times source. "It's almost Shakespearean. Not that I'm saying he'll end up a tragic figure, but he's closer than anybody thought one month ago, when resignation was unthinkable. But if an idea gets repeated enough times, before you know it, it becomes fact."

Indeed, one year ago Raines -- toasted as editor of the year by industry trade magazine Editor & Publisher -- was the subject of a 17,000-word profile in the New Yorker, which came complete with an appropriately weighty, statesman-like headline: "The Howell Doctrine."

Now, as wave after wave of criticism laps up against the Old Gray Lady, it appears Raines may be just trying to hang on to his job. If he were forced out, "It would be the most devastating thing to ever happen in his life," says Susan Tifft, a former Times reporter and coauthor of "The Trust: The Private and Powerful Family Behind the New York Times." "He's spent his entire professional life grooming himself, and preparing himself, and really living for this moment when he'd be able to lead the Times. He feels a real sense of mission about it."

"If that moment came and Arthur Sulzberger asked him to go, he'd consider it his last gift to the paper," says Tifft. "That's how he sees the Times."

Such a dramatic gesture would be unprecedented at the Times. According to historian Tifft, no top editor of the newspaper has ever resigned or been forced out under a cloud of controversy. (In the '80s, legendary editor Abe Rosenthal, whose stubbornness bordered on delusion, was gradually pushed out, but not for any specific event under his tenure.) Instead, the succession between editors at the family-controlled Times is often an ornately choreographed event with personnel moves planned out months, even years, in advance to assure a smooth transition of power at the only American newspaper that wields governmental-like power in its ability, even in the age of cable and the Internet, to dictate a national news agenda.

"Just because it hasn't happened in the past doesn't mean it wouldn't happen in the future," says Tifft. "The publisher strives always to do what's in the best interest of the New York Times. That's the star they steer by, even if that means dismissing friends he has installed. If in Arthur Sulzberger's judgment retaining Howell is damaging the Times, I don't think he'd hesitate to do it."

The theory is that by jettisoning Raines, the Times could stop the bleeding and begin to make its recovery. "If something unsettling happened that made the newsroom lose confidence in its editor, the cleanest and surest way to deal with the problem is to get rid of the editor," says Geneva Overholser, a former Times editorial page writer and currently a journalism professor at the University of Missouri. "But Arthur might view this differently. He'd say, I'm leading an institution with such tradition and confidence in its singularity, and widely viewed as the single strongest journalist entity in the country. Do I take such a drastic step as to fire the executive editor?"

Another question seems equally pressing: Who would replace Raines in the top spot? "Put yourself in Arthur Sulzberger's shoes," says Tifft. "You need a new executive editor who has the confidence of the staff, somebody who's ready to shoot down the pole into the fire truck. You have an upcoming election to cover, and you're trying to remake the arts and culture sections. You don't fire Howell Raines and then try to decide who's going to be executive editor." Trying to figure out the next move "is like staring at a chess board," says Tifft, who doubts the publisher will make a change at the top spot.

The newspaper's No. 2 executive, managing editor Gerald Boyd, remains an unlikely candidate since he's so closely tied to Raines, and like his boss has been badly damaged by the Blair affair. Complicating matters, though, is that Boyd is the paper's first black managing editor; that carries a lot of weight with Sulzberger, who once called diversity in the newsroom "the single most important issue" the Times faced.

"Getting rid of Gerald Boyd, that has larger repercussions," notes Tifft.

Some Times staffers point to Bill Keller as a possible candidate to replace Raines. Currently a columnist on the Op-Ed page, Keller served as managing editor for Raines' predecessor and was considered for the top spot. But by tapping him, Sulzberger would be admitting not one, but two mistakes: that Raines was the wrong person for the job, and that Sulzberger was wrong to pass over Keller in 2001.

The fact is, most of the newsroom was behind Raines' appointment two years ago. "The consensus was with Howell, not Bill Keller," says one former Times editor. "So what turned everything around? I don't get it. How the hell, in one and a half years, with news busting out all over, did the newsroom consensus turn against Howell? What the hell did he do?"

Critics say the only thing that happened is that Sulzberger let Raines be Raines.

After early journalism apprenticeships in his home state of Alabama at the Tuscaloosa News and Birmingham News, Raines joined the Times in 1978 as a national reporter and worked his way to the top.

Over the years Raines earned a reputation for his regal, autocratic and driving management style. Detailing his tenure as the Washington bureau chief, Tifft and coauthor Alex Jones wrote in "The Trust" that Raines "demanded that reporters stack books on their desks vertically instead of horizontally, and once ordered a news clerk to bring his office ficus tree out into the rain so it could be watered naturally. Privately, detractors turned his name into a verb: 'to Raines' meant to have slaves and not admit it."

Following Raines' stint in D.C., Sulzberger tapped him to become the Times' editorial page editor and invited him to be part of the paper's permanent brain trust, a new kind of triumvirate made up of the Times' publisher, executive editor and editorial page editor. During the '90s, as the Times' editorial page attacked the Clinton White House mercilessly over trumped-up scandals such as Whitewater and the Wen Ho Lee spy case, Raines grew closer to Sulzberger and became the obvious choice for executive editor when the job opened in 2001.

Before offering him the job, though, Sulzberger, well aware of newsroom complaints about Raines' penchant for showering attention on a small cadre of favored writers while ignoring others for months on end, insisted Raines not run New York as he had D.C. In effect, Raines was ordered to play well with others.

According the New Yorker profile, "Sulzberger told those he confided in, that he would have blocked Raines' promotion [to executive editor] if Sulzberger was not convinced that he had changed." The irony of Sulzberger telling Raines to abandon his star system, notes Overholser, is that "Howell Raines is the ultimate expression of Arthur's having his own star system."

The other glaring contradiction was that Sulzberger had dedicated himself to modernizing the Times, remaking the newspaper and particularly its culture. Yet Raines was clearly a throwback to an era of harsh, headstrong, I-know-what's-right Times editors such as Rosenthal and Turner Catledge (in the '60s and '70), who ran the newsroom however they damn well pleased.

Not surprisingly, Raines did not change his management style. Critics complained that it became ever more overbearing -- "the republic of Fear," some dubbed it -- as he and his loyalists on the masthead began to dictate the content of the newspaper, and especially Page 1; and that, instead of letting reporters and lower-level editors ferret out the news and important analysis stories, assignments were coming from the top down.

That tension was only exacerbated following the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, when the top editors on the masthead took control over stories coming out of the D.C. bureau, essentially assigning that day's political stories from New York. It was an unprecedented level of micromanagement, and it infuriated editors and reporters, many of whom began to flee the newspaper.

Last year, well before Jayson Blair, that approach created an uproar inside the Times. The Times wrote extensively about a campaign to open the prestigious Augusta National Golf Course to women; the newspaper clearly seemed to believe the course should be opened. When two sports columns dared to question that policy, they were spiked, a move that provoked an intense national debate among journalists and others. Raines eventually backed down and published the columns, which only highlighted how timid the essays were to begin with. But the episode damaged Raines badly inside the newsroom, where nobody could recall columns ever getting killed in such a manner in the past.

Adding to the unease was Raines' philosophy that even though the newspaper was published just once a day, the staff ought to compete with cable news and Internet outlets by relentlessly breaking news. The approach often left the newsroom drained, as did Raines' demand that national reporters spend more time on the road chasing stories. As one staffer complained to the New York Observer last year, under Raines' rules, "basically, if you have a family, you're f---ed."

Again, the approach was in direct contradiction to Sulzberger's often public proclamations about making the Times a family-friendly work environment. Staffers made sure the publisher, who put in several years as a reporter himself at the Times, understood the gap between his words and Raines' deeds. But Sulzberger opted to let Raines manage the paper as he saw fit.

Now the publisher has to decide whether that was the biggest mistake of his career.

"I've called Howell Raines a high-risk editor," says Overholser, who served as editor of the Des Moines Register for seven years. "And we've seen both the risks and the rewards. The extraordinary success covering 9/11, that was Howell Raines. But exhausting the newsroom and creating a star system was also very much Howell Raines. He's an exceedingly talented man, very passionate and hard-working. But the newsroom has found out he's not terribly open to criticism."

Some inside the newsroom, like Dwyer, are hopeful Raines can recover. "Howell has to assert himself as a wise presence and a trustworthy one. I certainly think he can do that."

Others are less sure. "I'm flabbergasted by it all," says a senior Timesman. "It's heartbreaking. But have we hit bottom yet? The top keeps spinning."

Shares