"Some years ago," Mark Rudd says, "I developed this formulation: The Vietnam War drove me crazy. Now, that doesn't explain why it drove me crazy and it didn't drive other people crazy. But I think in actuality the Vietnam War drove a lot of people crazy."

Sitting at a sidewalk cafe table in New York's Soho neighborhood, Rudd isn't likely to attract much attention. He looks like a shaggy, stocky, aging hippie turned academic, which is pretty much what he is. (He teaches at a junior college in Albuquerque, N.M.)

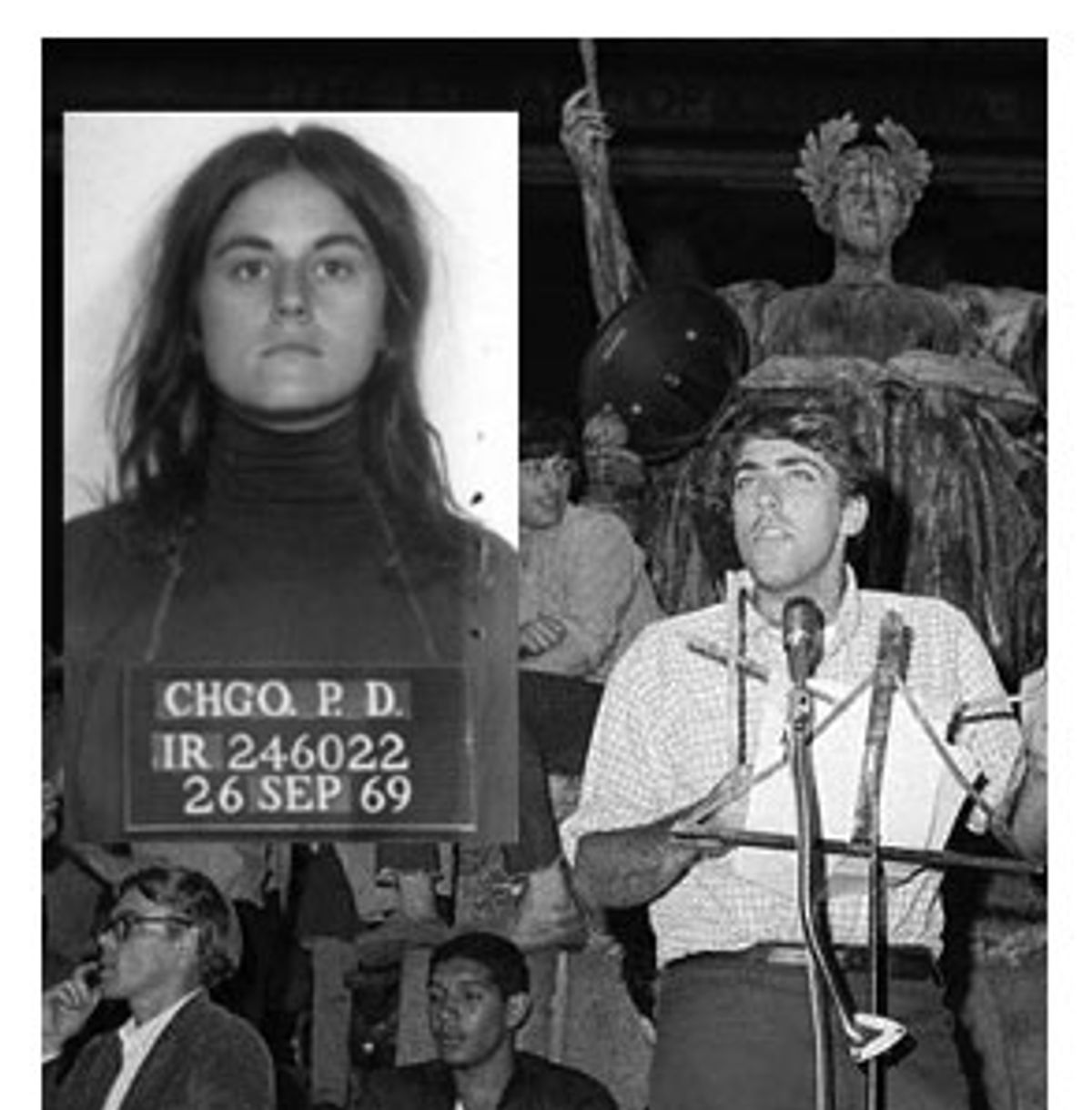

But 34 or 35 years ago, in another era and what must sometimes seem to him like another country, Rudd was a national counterculture celebrity. As head of the Columbia University chapter of Students for a Democratic Society, he led the antiwar demonstrations that virtually shut down the Columbia campus in April 1968, occupying the president's office and holding the college dean prisoner (as well as producing the infamous slogan, "Up against the wall, motherfucker!"). The following year, he was one of the founding members of Weatherman, the revolutionary faction that took over SDS and essentially devoured it. (The group's name, of course, derives from the lyrics to Bob Dylan's "Subterranean Homesick Blues": "You don't need a weatherman to know which way the wind blows.")

Less than a year after that, by the spring of 1970, he was a fugitive terror suspect, fleeing federal charges that he'd planned bombings and incited riots in various Midwestern cities. Three Weathermen had blown themselves up while building a bomb in a Greenwich Village townhouse, no more than a mile from where Rudd is sitting today. To the group's everlasting shame, that bomb was intended for an officers' dance at Fort Dix, N.J., where it presumably could have killed not only military personnel but their civilian dates and whoever else might have been in the building.

In the wake of the townhouse explosion, authorities finally grasped that the Weathermen, although small in scale and limited in capacity, were earnestly dedicated to the violent overthrow of the United States government. Like two dozen or so other core members, including such movement stars as Bernardine Dohrn, Bill Ayers, David Gilbert, Kathy Boudin, Cathy Wilkerson and Brian Flanagan, Rudd lived "underground," moving from city to city under assumed identities and holding a series of menial jobs, for more than seven years.

Dubbed the Weather Underground, the group carried out several more bombings in the 1970s, including high-profile attacks on the U.S. Capitol mailroom and New York police headquarters. Perhaps the Weathermen's greatest achievement, such as it was, came in September 1970, when they helped LSD guru Timothy Leary escape from a California prison and flee the U.S. with a forged passport. Leary lived in Eldridge Cleaver's Black Panther compound in Algeria until the two had a falling out, but was ultimately recaptured by U.S. agents in Afghanistan. In a final twist not mentioned in Green and Siegel's film, once Leary was back in prison he reportedly ratted out his Weather Underground allies to the FBI in exchange for early release.

As misguided and counterproductive as the Weather Underground's activities may have been, after the townhouse bombing the group never again planned attacks against human beings. Their post-1970 bombings were symbolic in nature and happened at night when the buildings were empty. For all the vitriol heaped on the Weather Underground by other leftists -- and especially by ex-leftist neocons like David Horowitz and Ronald Radosh -- it never killed or injured anyone except its own members. (In this regard, it's striking that right-wingers routinely employ the excesses of Weatherman to paint the entire left as anti-American terrorist sympathizers, while the left is either too civil or too cowardly to use the hateful acts of Timothy McVeigh, Eric Rudolph and James Kopp to attack conservatives in general.)

Maybe all this history explains my first question to Rudd, the one to which he responds above: "Were you just completely fucking nuts?"

His answer, and I suppose mine too, having talked to him and watched Sam Green and Bill Siegel's documentary film, "The Weather Underground," is yes and no. The movie (now playing in New York, with Chicago, San Francisco and several other cities to follow over the summer) is certain to leave people arguing on the sidewalk after they see it. Some veterans of the New Left's political wars will surely feel it's a little generous to the Weathermen, a group who could be described as combining Cultural Revolution-style ultra-left rhetoric with Keystone Kops incompetence, and they probably have a point.

But for most viewers under 40 or thereabouts, who will know little or nothing about the events in question and for whom the history of the late '60s and early '70s is a newsreel blur of rock concerts, assassinations, Volkswagens, G.I.s with Zippo lighters and jerky Richard Nixon poses, "The Weather Underground" will arrive with the force of revelation. It does something that's almost impossible to do in works of history -- it conveys a sense of what the past actually felt like.

And the past in this case, the past of 1968 through 1970 or so, was completely fucking nuts. As Green and Siegel's impressive collection of video footage (a great deal of which I've never seen before) makes clear, the internal feuds in the antiwar left that drove a handful of radicals to declare war on their own country didn't happen in a vacuum.

By 1968, the Vietnam War was going poorly and public opinion was beginning to swing against it. The weekly body count of dead U.S. soldiers, often in the hundreds, had become a major story. The Tet Offensive, beginning in January -- during which the North Vietnamese briefly occupied the U.S. Embassy in Saigon -- made clear that we were not only not winning the war, we might be losing it. In March, the men of Charlie Company, 11th Brigade, Americal Division, under the command of Lt. William Calley, massacred more than 300 unarmed civilians, including women and children, in the Vietnamese village of My Lai. (The public didn't learn about the My Lai massacre for a year and a half, until journalist Seymour Hersh published his legendary exposé.)

In April, the same month Rudd led the student uprising at Columbia, the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated in Memphis and black neighborhoods in more than 100 cities exploded in violent outrage. In May, the student-worker rebellion in Paris brought Charles de Gaulle's government to the brink of collapse. In June, Sen. Robert F. Kennedy, who seemed likely to become the next president and had vowed to end the war, was assassinated in Los Angeles. In August, the shattered Democrats held their convention in Chicago and were upstaged by pitched street battles between radical demonstrators and Mayor Richard Daley's thuglike police force, while halfway around the world a different set of thugs, commanding Soviet tanks, rolled into Czechoslovakia to crush the "Prague Spring" reform movement.

All that in eight months. You could make an argument that 1969, which brought the Manson Family murders, the Chicago Eight trial, Woodstock, Altamont and the police killing of Black Panther leader Fred Hampton under what might generously be described as suspicious circumstances (he was almost certainly murdered in his sleep), as well as the SDS split and the emergence of Weatherman, felt even more apocalyptic.

A lot of people, not all of them on the left, believed that Che Guevara-style Third World revolution was bound to come to North America. To many intellectuals, Western civilization seemed on the verge of destroying itself in one last violent paroxysm. Against this background, the most surprising thing about the Marxist guerrilla movement that emerged from the New Left in 1969 is how small and ineffective it actually turned out to be. (Even the largest and most famous Weatherman action, the "Days of Rage" riots in Chicago in October of 1969, involved no more than 500 people, when organizers were expecting tens of thousands.)

"There was so much violence at the time," Rudd says. "All the violence, especially the violence we were opposing, it permeated us. It was like the interpenetration of opposites."

Rudd had been to Cuba early in 1968, and like many radicals of the time was hypnotized by the cult of Che and the Cuban Revolution with its model of foquismo, the argument that a small revolutionary vanguard could galvanize society and draw the masses to its cause. "It was almost like a religious revelation," he says. "The revelation was that there was a war going on in the world, and you had to choose sides."

But most radicals, even those with Che and Fidel posters on their walls who openly rooted for Ho Chi Minh and the Viet Cong, never tried to plant bombs in government buildings or got involved in harebrained schemes to organize "revolutionary working-class youth." (Rudd was once beaten up by kids at a Midwestern drive-in during one of these organizing efforts.)

Rudd says that to this day he can't explain why he went so far into revolutionary madness. At this point he comes off as a genial, entirely sane, middle-aged man, who talks about his past with the same combination of rueful nostalgia and good humor other people might display in discussing Woodstock or a college romance or an acid-fueled motorcycle voyage across the Southwest. "I don't think I was that different from most white middle-class antiwar people," he says. But Weatherman provided "a group or a gang or a clique" that no outside criticism could penetrate. "You develop your own philosophy and it grows more and more intense, the way a religious cult might develop."

As Weatherman transformed SDS from a broad public movement to a small revolutionary cadre between the summer of 1969 and the spring of 1970, most of its membership dropped away. Rudd stayed. "The people who managed to break free of that gravitational pull -- I actually honor them, you know?" he continues. "They got out and I didn't. Maybe I was weaker."

He held a leadership position on "the Weather Bureau" until about the time of the townhouse bombing in March 1970, although he says he was not directly involved in planning or building the bomb. A day or two before the disaster, Rudd says, he learned that the device was intended for the Fort Dix dance. "In retrospect," he says, choosing his words carefully, "I've always wished that I had had the presence of mind to take some action to stop it."

But Rudd's mentality at the time, and the group's, was entirely different. He remembers thinking, "'We've got to carry this through. We've got to carry out armed attacks against the imperialist enemy.' I guess it must have been a terrorist state of mind."

When asked the obvious question -- whether his experience offers him any insight into the thinking of people who blow themselves up in Tel Aviv supermarkets, or fly airplanes into crowded buildings -- Rudd laughs in a way that lets you know he isn't actually amused.

"I don't think insight is the right word," he says. "I think it's more like, do I think I could ever be that twisted? I certainly don't have the same insight as George W. Bush, who knows for a fact that there is good and evil in the world, and which is which. I think there's a lot of evil in the world."

In Green and Siegel's present-day interviews with Weather Underground veterans, Rudd and former comrade Brian Flanagan (today the owner of a Manhattan bar) appear as the movement's voices of repentance. In one wrenching scene near the end of the film, Flanagan stands at the site of the West 11th Street townhouse that blew up in March 1970, killing Diana Oughton, Ted Gold and Terry Robbins. (Fellow Weathermen Kathy Boudin and Cathy Wilkerson were also in the house, but escaped alive.) "I come by here all the time," says Flanagan, in tones of weariness, almost exhaustion. "It never really gets any easier."

But the Weather Underground's glamour couple, Bernardine Dohrn and Bill Ayers, seem strangely unaware of how they come off today, and at least half-trapped in the ideology of the past. (Dohrn was originally planning to do interviews to promote the film, but apparently thought better of it.) Seen in newsreel footage from 1969, they come off more like style-conscious actors playing revolutionary leaders than the real thing: Dohrn lectures the "bourgeois pigs" of the mainstream press while wearing a micro-miniskirt and Sophia Loren sunglasses; Ayers saunters through a crowd with a detached, rock-star swagger. You could say they were imitating Jane Fonda and Bob Dylan, respectively, but Dohrn and Ayers had so much street cred at the time it almost might have been the other way around.

Since emerging from underground around 1980, Dohrn and Ayers have held lefty sinecures at universities (Dohrn at Northwestern, Ayers at the University of Illinois at Chicago). Like most other Weatherman veterans, neither went to prison, largely because the FBI's notorious COINTELPRO program broke so many laws while pursuing them that the evidence gathered was worthless. (David Gilbert and Kathy Boudin are serving life sentences for a 1981 armored-car robbery in which a police officer was killed, but that crime occurred after the Weather Underground had disbanded and most other members had surfaced.)

Perhaps because they're coddled by institutional life and surrounded by like-minded people, perhaps for some other reason, neither Dohrn nor Ayers displays even the faintest evidence of penitence or apology, nor any consciousness of the fact that almost everybody else in America -- left, right or center -- thinks they were completely out to lunch. (Dohrn now insists she was kidding when she praised the Manson family for "offing those rich pigs with their own forks and knives," although no one who knew her at the time seems to believe that.) Even in the wake of Ayers' self-mythologizing memoir, "Fugitive Days," which had the unique karmic misfortune to be published in September 2001, they seem to lack any rational perspective on the troubling role they played in 20th century American history. (In what may have been the worst timing in journalistic history, an adulatory interview with Ayers appeared in the New York Times on the morning of Sept. 11, 2001, under the headline, "No Regrets for a Love of Explosives.")

Weather-haters may reject the highly textured historical context supplied by Green and Siegel's film, the notion that, as Rudd puts it, "the establishment of the context of violence somehow explains the violence of the individual terrorist." But nothing in the movie seeks to justify the Weathermen's specific tactics or arguments. In fact, understanding Weatherman as one manifestation of a near-pathological period in American history -- as a symptom of the New Left's disintegration, rather than its cause -- reduces the group's overblown rhetoric to human scale, and makes clear how pathetic its grandiose ambitions really were.

New York University professor Todd Gitlin, the onetime SDS leader ousted by Weatherman in 1969, says in the film that the group's apparent willingness to kill for its beliefs, at the time of the townhouse bombing, brought it into the same category of ideology-driven murderers as Hitler and Stalin. This is grossly overstated -- the Weathermen never held any power and, once again, never actually killed anyone on purpose -- and no doubt results from Gitlin's legitimate sense of grievance against Dohrn, Ayers, Rudd and company.

But there's a germ of truth beneath Gitlin's bluster, in the sense that the utopian dreams of the '60s left (which were, at least arguably, always ridiculous) were irreparably smashed in the fall and winter of 1969-70. That season also brought the Manson arrests, the My Lai revelations, the Hampton killing and the acid nightmare at Altamont Speedway. The explosion on West 11th Street in March, maybe not so earth-shattering in itself -- a few pampered kids playing with explosives -- was the last nail in the coffin.

For Mark Rudd's part, he says those experiences 30-odd years ago have made him an absolute pacifist. Most people would probably disagree with his view that there's no moral distinction between a soldier following orders in Iraq and a suicide bomber in Jerusalem, but at least he's consistent. "No one should kill anyone, for any reason," he says. "No government violence, nothing. None of it is justified. The only solution I can see is to advocate for pacifism everywhere in the world. It solves the problem of good and evil."

"The Weather Underground" suggests uneasy parallels with today's America, at least insofar as the film depicts a period of rapid and unpredictable change, in which the U.S. government seems to have grand imperial schemes. For his part, Rudd hopes today's activists will learn from his example. The post-Seattle anti-globalization and antiwar movements have "better logic" than the Weathermen, he says. "Their actions are better thought out. But I still think they have to inform all that with pacifism. I take an absolute stand on that. If you look at activist movements in history, the ones that are most successful are the ones that are most disciplined, that say, 'We will not harm people, we will not harm property.' Because then you capture that moral high ground. I am absolutely convinced, for example, that the Israelis could not possibly have stood up to a nonviolent resistance movement" by the Palestinians.

He pauses again, looking around him at the calm, sunny New York street scene. "I'm ashamed of what we did to SDS," he says. "I think Todd Gitlin is right when he says in the movie that we hijacked SDS. We destroyed SDS.

"I'm also ashamed that we raised the issue of violence within the movement. I think we contributed to the discussion of anti-imperialism, which was absolutely essential. But that in itself led us to take that last step, to become anti-imperialist guerrillas."

Rudd laughs again. It almost seems as if he's been over this stuff in his head a million times, but it still surprises him a little when he talks about it. "You know what? If Gitlin and other ex-New Left people choose to hate me, that's quite all right with me. Maybe they have some elements of truth on their side."

Shares