Last Wednesday, Attorney General John Ashcroft had a challenge before him. He would appear the next day before a relatively hostile House committee, and he wanted to avoid any “Ashcroft Faces Intense Grilling” headlines in the papers.

The last time Ashcroft appeared before the House Judiciary Committee, Sept. 24, 2001, seems like a different era. The committee comprises members of Congress who had voted against the USA PATRIOT Act — which gave law-enforcement agencies broad powers almost immediately after the 9/11 attacks in an attempt to prevent similar catastrophes — as well as those who proudly voted for it, together with a few members whom he saw as revisionists: those who voted for the bill but who have since become critical of both it and Ashcroft. To add insult to injury, only two days before last week’s testimony, the Department of Justice’s inspector general issued a harshly critical review of the Justice Department’s post-9/11 detentions of illegal immigrants.

So the day before, Ashcroft began to prepare. He held a private meeting with 10 U.S. attorneys from around the country to gather anecdotal information he could use. He skipped the annual White House radio-television correspondents dinner, where he was to be the guest of Fox News. And he honed a very aggressive opening statement — including the proposal of three new anti-terrorism laws — that in many ways made the House committee his own turf. He wasn’t going to “just sit there and be a punching bag,” according to a Justice Department source.

To a large extent, the plan worked. “Ashcroft today asked Congress for much tougher powers to fight the war against terror,” CNN’s Lou Dobbs reported that evening. “Ashcroft said that the PATRIOT Act has weaknesses, weaknesses that terrorists could exploit.” The New York Times proclaimed: “Ashcroft Seeks More Power to Pursue Terror Suspects.” The Atlanta Journal-Constitution ran the headline “Federal Death Penalty Use Grows; Bombings Likely to Be Capital Cases.”

These were assuredly not the headlines that Ashcroft’s critics on the House Judiciary Committee had been dreaming of the night before. Before the hearing, after all, Democratic staffers were handing out fliers alleging that the PATRIOT Act had been misused in a number of ways. Clearly, Democrats had hoped to draw a little blood.

The three key proposals highlighted by those headlines were only a part of what happened at the hearing, of course. Ashcroft was pointedly questioned about his post-9/11 policy and actions not only by Democrats but also by the Republican chairman of the committee, James Sensenbrenner Jr. of Wisconsin. But, by and large, Ashcroft managed to go to the committee, get his message out, and quite possibly emerge stronger than before.

“Oftentimes there are some members of Congress who think that they’re going to bloody him up, but at the end of the hearing they are consistently disappointed at their inability to land any blows,” says a source close to Ashcroft. The source says that isn’t necessarily because of Ashcroft’s political skills, however, “but because of how out of touch these members of Congress are with the American people. A lot of time, the more they attack him on some of these issues, the stronger his support becomes.”

The hearing was, one Democratic Senate staffer groused this week, “archetypical Ashcroft.” The staffer, who asked not to be identified, surmised from his Ashcroft-watching experience that the attorney general “knew he was in for some close questioning by some of the representatives and that a new death penalty for terrorists would likely be in any headline about the hearing.” His presentation was therefore “clearly orchestrated to capture the headline and swamp the pent-up frustration by committee members over the Justice Department’s lack of cooperation.”

That isn’t a strictly partisan perception. There are Hill Republicans who — albeit somewhat more admiringly — also viewed Ashcroft’s testimony as a clever way to outmaneuver their committee. Some note that they have issues not only with the three proposed laws — a new death penalty isn’t likely to deter the suicidal terrorists of al-Qaida — but also with the fact that Ashcroft didn’t present them with copies of the proposed laws, making it difficult to prepare or to comment on the laws before Ashcroft spoke.

It was just the latest move by a man whose considerable political acumen many have — sometimes begrudgingly — come to appreciate.

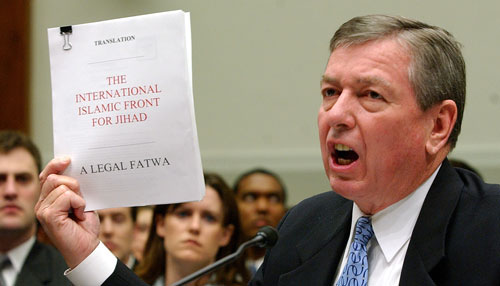

The source close to Ashcroft claims that “overall the media coverage of the PATRIOT Act is done in a negative light.” Ashcroft believes, the source said, that in his rare appearances before the House and Senate Judiciary committees, it is crucial to keep his opponents from getting the upper hand and instead to “remind the American people that terrorism has not ended and to make the case for what he’s doing on the war on terrorism.” In a December 2001 hearing before the Senate Judiciary Committee, Ashcroft similarly stole his questioners’ thunder by bringing with him an al-Qaida training manual that he deftly wielded before the cameras.

While a repeat performance with the training manual seemed unlikely, Ashcroft knew that some members of the House committee smelled blood. Tensions predated the inspector general’s report: Ashcroft had been scheduled to testify before the committee last summer, but when he refused to offer his written testimony ahead of time, as is customary, Sensenbrenner angrily canceled the hearing. In a June 2002 interview with CNN, Sensenbrenner said that in its attempt to prevent terrorism, law enforcement didn’t need “to throw respect for civil liberties into the trash heap.” On April 1 of this year, Sensenbrenner and the ranking Democrat on the Committee, Rep. John Conyers of Michigan, submitted some tough questions to Ashcroft. Most recently, after Sen. Orrin Hatch, R-Utah, chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee, floated the idea that Congress should consider making the USA PATRIOT Act permanent — the bill is due to expire in 2005 — Sensenbrenner told the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, “That will be done over my dead body.”

Sensenbrenner spokesman Jeff Lungren downplays any personal issues between his boss and Ashcroft. “Everyone recognizes that there’s always a tension between Congress’ interest in getting information and the Department of Justice’s — or any agency’s — general reluctance to share all sorts of information with Congress,” he says. Sensenbrenner and Ashcroft have a fine working relationship, Lungren insists, meeting every “six or eight weeks or so.”

At last week’s hearing, though, Sensenbrenner declared his support for the controversial USA PATRIOT Act to be “neither perpetual nor unconditional.” Sensenbrenner, who unlike his Senate counterpart Hatch has sought an aggressive oversight role for his committee, spoke against “short-term gains which ultimately may cause long-term harm to the spirit of liberty and equality which animate the American character.” In that spirit, he and others on the House Judiciary Committee had some rather probing questions for the attorney general. Sensenbrenner was most irate about Ashcroft’s revision last summer of the so-called Levi guidelines, introduced by Ford administration Attorney General Edward Levi, which prohibited FBI agents from investigating demonstrations and religious services covered by the First Amendment unless “specific and articulable facts” indicated criminal activity. That Ashcroft revised these guidelines with zero consultation with Congress had the chairman most upset.

Others had bones to pick, too. Rep. Maxine Waters, D-Calif., was worried about the way the Justice Department was using the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act. Her fellow California Democrat, Rep. Howard Berman, brought forward issues in the inspector general’s report about the “hold until cleared” policy — whereby illegal immigrants are held in custody until it can be proved that they have no terrorist ties, a complete reversal of the judicial system’s presumption for American citizens that they’re innocent until proved guilty.

“You said in your statement, ‘We must not forget that our enemies are ruthless fanatics,'” said Rep. Bill Delahunt, D-Mass. “But the solution is not for us to become zealots ourselves so that we remake our society in the image of those that would attack us.”

But regardless of the occasionally heated rhetoric from his congressional inquisitors, nothing seemed as compelling as the life-or-death situations the attorney general was able to describe. Listing the names of victims of 9/11, as well as of soldiers who had died in Afghanistan and Iraq, the attorney general reminded the panel of the continued threat of terrorism, mentioning a recent fatwa — “The Legal Status of Using Weapons of Mass Destruction Against Infidels” — issued by a Saudi imam with links to al-Qaida. What seemed to get the lion’s share of the media’s attention was Ashcroft’s request for more powers, because, he said, the law “has several weaknesses which terrorists could exploit, undermining our defenses.”

Justice Department spokeswoman Barbara Comstock says Ashcroft was merely trying to communicate some ideas for follow-ups to the PATRIOT Act, as requested by Congress in January. After an in-house document containing ideas for follow-up legislation to the PATRIOT Act was leaked that month — the infamous “PATRIOT II” — members of Congress told the Justice Department that “we want to discuss these things with you when you want to revise the act,” she said. “So we’re like, Here are some things to start the dialogue back and forth.” Comstock doesn’t see the proposals as controversial, and she points out that one provision from PATRIOT II was inserted into the Amber Alert bill earlier this year and passed into law: a legal tweak including airplanes in the definition of mass-transit vehicles. Previously, a U.S. district judge had struck down one of the many charges against Richard Reid, the would-be shoe bomber, ruling that an airplane did not legally constitute a “mass transit” vehicle.

Ashcroft’s first proposal would change the 1996 anti-terrorism law against providing material support for a terrorism group to include those who train with terrorists, like the so-called Lackawanna Six. The question about whether the current law, which prohibits providing “personnel” to terrorists, also prohibits providing one’s self has prompted different answers from different courts: The 9th Circuit Court of Appeals upheld a ruling that the prohibition against providing “training” or “personnel” to a designated terrorist group was unconstitutional, the court argued, because the terms weren’t “sufficiently clear as to allow persons of ordinary intelligence a reasonable opportunity to know what was prohibited.” In July 2002, U.S. District Judge T.S. Ellis III of Virginia disagreed with the 9th Circuit in a ruling against “American Taliban” John Walker Lindh, ruling that the statute was not vague, since “personnel” clearly applies to those who put themselves under the “direction and control” of a terrorist organization and “does not extend to independent actors.”

“We must make it crystal clear that those who train for, and fight with, a designated terrorist organization can be charged under the material-support statutes,” Ashcroft said at the hearing. However logical that may seem, it is at the very least disputed in the courts, and it is not so crystal clear that Congress’ intent with the 1996 law was intended to be a blanket criminalization of any contact with a terrorist group. The April 1996 House-Senate conference committee report on the bill, according to Hatch’s office, stated that “material support” did not include providing terrorist groups with medicine or religious materials.

The second provision would allow the death penalty in cases when terrorists sabotage a national defense installation, a nuclear facility, or an energy facility, resulting in deaths. The third provision would make defendants in terrorism cases — alongside organized crime, drug offenses and gun crimes — eligible for pretrial detentions, Ashcroft said.

Justice Department spokeswoman Comstock reports that “during the hearing when he brought up those three provisions, there was no push-back.” The committee didn’t say much — or ask much — about them, she says, which makes sense to her since they seem so logical. “A lot of these provisions, when people talk about them individually, they’re just common sense. You know how people say they don’t like Congress but they like their congressman? People say they don’t like the PATRIOT Act, but when you ask them what don’t they like about it and you go through the specifics of the bill, their reaction is different.”

But when Ashcroft described his proposed new laws, they did not exist in paper form for the Judiciary Committee. That made any real debate about them essentially impossible. Sensenbrenner spokesman Lungren says that his boss will defer commenting on the proposals until he actually sees them. “We don’t get wrapped up in any concern about proposals until they are sent up,” he says. In that vein, the PATRIOT II draft didn’t concern Sensenbrenner, Lungren says. “There are people hired at the Department of Justice and their job is to throw ideas at the wall as to the best way to fight the war on terror. Some stick and some don’t.”

But Tim Edgar, legislative counsel of the American Civil Liberties Union, was quicker to be critical of the proposals. Even before diving into the specifics, Edgar says “those three things that he mentioned were all PATRIOT II provisions” — even though the Justice Department insists that the leaked January document was a very rough work in progress, still being evaluated and critiqued.

More specifically, Edgar supports the 9th Circuit court’s interpretation of the 1996 anti-terrorism law’s definition of “material support” and opposes broadening the definition. “The government has been forced to make a somewhat strained argument” in the Lackawanna case, Edgar says, where the six Yemeni-Americans, who have all pleaded guilty, were “going to attend what they thought was paramilitary camp, which turned out to be a terrorist training camp.” (As part of their plea agreements, many of the defendants dispute Edgar and admit having more knowledge of where they were going.)

The original law focused on supporting a terrorist group, not merely associating with them, he says. “It’s already a crime to engage in any kind of conspiracy to harm Americans,” Edgar says. “This proposal would eliminate the need for them to show someone actually intended to do something wrong.”

Regarding the other two acts, the ACLU already opposes the death penalty and pretrial detentions when it comes to those accused of being part of organized crime, or committing drug or gun crimes. The Justice Department’s argument that if these tools can be used against mobsters they should certainly be available to wield against terrorists makes little sense to him — he characterizes it as saying “If the law’s really terrible in one area, we should extend it to every area.” A Democratic Senate staffer says that the new death penalty proposals at first blush seem odd — in that al-Qaida bombers tend to be suicidal to begin with — as well as possibly redundant. “It seems somewhat symbolic,” the staffer says. “It’s very unlikely that if there were an act of terrorism that killed people, the government could not find a federal death penalty punishment for it.”

Those criticisms weren’t voiced at the hearing, of course, because the committee wasn’t prepared. Throughout the post-9/11 era, the attorney general has fought his critics like the all-elbows scrappy pickup basketball player he proves himself to be in occasional games at the DOJ gym. “The A.G. gets what this is all about — preventing another terrorist attack,” says his deputy chief of staff, David Israelite. “And if the price for doing that is attacks from a bunch of editorial boards and a bunch of liberal members of Congress, so be it.”

On October 3, 2001, when Ashcroft thought Senate Democrats were unnecessarily dilly-dallying over passage of the PATRIOT Act, he slammed the “rather slow pace” at which the Democrats were proceeding. “Talk won’t prevent terrorism; tools can help prevent terrorism,” he said to his former Democratic colleagues, adding that his comments were “to describe to them the kind of urgency that I feel that is necessary.” At a Senate hearing two months later, Ashcroft decried “those who scare peace-loving people with phantoms of lost liberty,” to whom he said, “Your tactics only aid terrorists.”

Ashcroft later said that he wasn’t referring to any members of Congress with that charge; regardless, he didn’t say anything quite as harsh to his opponents in Thursday’s hearing. But he wasn’t exactly subtle, either. His opening statement relayed how, during Operation Enduring Freedom, “on the wind-swept plateaus of Afghanistan, some American military commanders read a list every morning to their troops — names of the men and women who died on September 11. It was a stark reminder of why they were there.” He then proceeded to list some of the 9/11 victims, taking great care to pronounce their names correctly. His prepared remarks spelled them out phonetically: “Joseph Maffeo [maf-FAY-o],” the document read. “Manny Del Valle [del-VOL-lay]. Charles E. Sabin [SAY-bin].”

Going on to name soldiers who had died in Operation Enduring Freedom and Operation Iraqi Freedom, as well as conjuring forth the memory of the “343 firefighters and 71 police officers [who] died in the line of duty,” Ashcroft reminded those assembled that the bill so many of them were eager to pick apart had passed the House of Representatives 357-66 and the Senate 98-1. He pointedly noted that “despite the terrorist threat to America, there are some — both in Congress and across the country — who suggest that we should not have a USA PATRIOT Act.” Unquestionably referring to Sensenbrenner, among others, Ashcroft noted that “others who supported the act 20 months ago now express doubts about the necessity of some of the act’s components.” Making no bones about it, Ashcroft said, “Our ability to prevent another catastrophic attack on American soil would be more difficult, if not impossible, without the PATRIOT Act.”

His responses to questions from the committee continued the trend. About the inspector general’s criticisms that there were serious problems with the way illegal immigrants were detained in the months immediately following 9/11, Ashcroft said, “You have to remember what the situation was in New York. When this was happening, ground zero was still smoldering; the FBI was operating out of a parking garage following a lot of leads and uncertainty about what might happen next — not only what happened last.”

After nearly five hours of testimony, Sensenbrenner told Ashcroft he could go “put his feet up.”

“I know that you feel like coming before us is like appearing before the Inquisition,” Sensenbrenner said, sounding slightly defensive. “I think this shows that the system is working.”

It seems to be working well for Ashcroft. His theoretical new powers not yet committed to paper, no one in Congress seems willing to organize opposition against them. And he continues to stand, relatively unopposed.