In Nicholson Baker's phone-sex novel "Vox" the male interlocutor poses a question to his female counterpart. "So if you walked into a room," he says, "and there was an armchair, and a table, and on one end of the table was a TV and a VCR and an X-rated tape, and at the other end of the table was some book of Victorian pornography, what would you choose?" And she answers, "The Victorian pornography, no question." "That's incredible to me," he replies.

It's what she rightly calls "the classic opposition," the belief that men like to look and women like to imagine. And while you can't doubt that there's at least a kernel of truth in it, you also have to question the unspoken assumptions behind that opposition: Does visual representation -- a category that, besides porno movies and magazines, would have to include all movies, photographs and painting -- necessarily limit our imagination? Or can visuals be an incitement to our own fantasies? For all the women I know who have said they prefer written to visual erotica, I've known plenty who get turned on by visual erotica. And if men were sexually unmoved by erotica that requires some imagination, how do you explain the proliferation of phone-sex lines -- or, for that matter, "Penthouse Forum"?

The editors of the new collection of coffe-table erotica, "Women by Women: Erotic Photography," attempt to make a case that women photographers take a different approach to visual erotica. The book may be more interesting for how it fails to support that claim than for the ways it succeeds in buttressing it.

There is a striking difference between the explication of this work in Sophie Hack and Stephanie Kuhnen's introduction than in the work itself. Hack and Kuhnen make claims that are not supported by the photos that follow. They claim that male photographers work only with bodies that are "young and of classical perfection." But the majority of the women included in "Women by Women" could easily be included in men's magazines. And then there is the larger claim that men turn their subjects into objects (how then to account for female pornographers like the photographer Suze Randall?) and that women photographers allow their models to make "self-esteem, self-awareness and strength a visible source of attraction."

That claim is both true and false. I think the difference Hack and Kuhnen are talking about does exist, but it exists between what we think of as porn and what we think of as erotica. That is not a differentiation I usually like to make. Writers like Lisa Palac have rightly said that it's usually a distinction used in a snobbish way -- "If it turns me on, it's erotica. If it's crass enough to turn you on, it's porn." But there's no denying the difference between work that exists for the immediate gratification of the viewer (which, as a fan of porn, I don't condemn) and work that aims for a subtler, more insidious means of turning on the viewer.

You can see the difference if you look at the photos the fetish photographer Steve Diet Goedde has taken of the porn star Aria Giovanni and the photos you can find of her in men's magazines. To state the difference in the most simplistic terms, in Goedde's work, the emphasis is not just on Giovanni's boobs or pussy, but on her as a whole.

She is a fantasy figure in both, and the models included in "Women by Women" are no less fantasy figures. There's nothing wrong with that. If someone is dealing with fantasy, whether in a sci-fi novel or an erotic photograph, I see no reason why they should have to replicate reality. It's silly to claim, as Hack and Kuhnen do, that a model turned into a fantasy has put herself at the mercy of the photographer. Presenting yourself as a sexual fantasy is one of the most powerful positions you can put yourself in. Most of us, if we were honest, would admit to wanting to be able to trigger somebody's fantasies.

Were the photos in "Women by Women" presented without crediting the photographers, it would be hard to tell whether they were shot by a man or a woman. Still, the photos here feel different. It's not a case of their being "softer." That's only a politically correct use of the canard that when it comes to sex women are interested in the gauzy and prettified. Some of the work here, like Marie Accomiato's soft-focus sepia print of a pregnant woman, do fall into that category. Maybe the best we can come up with is to paraphrase Justice Potter Stewart's famous definition of pornography: I don't know what female erotica is, but I know it when I see it. But, like those Goedde photos of Aria Giovanni, the photos in "Women by Women" seem more interested in the totality of the model, in a low-flame sort of a turn-on rather than an immediate one.

One of the things that contributes to that impression is the reality of the settings. Some, like those in the photos of British fetish photographer Emma Delves-Broughton, are stylized in a manner befitting the stylization of fetishism. In one of her shots, a model poses against a black, pebbled background that offers the tactile sleekness of rubber or leather, and in another a model crouches atop a wood and glass table with a zebra-print rug beneath. But by and large, we are looking at rumpled beds, bare mattresses, hotel rooms, a bathtub in a rustic country bathroom (in a shot by Ellen Auerbach), or a deep-red coffee shop in Ivana Ford's photo of a model, nude from the waist down. Porn photo sets almost always seem to take place in obviously fake bedrooms or offices (in Penthouse's case, in what you might get if you hired the interior designers of Caesar's Palace to make over your Miami mansion).

The ordinariness of some of the settings, even those whose spareness is used to impart a certain stylization, grounds the models in a recognizable world and that, in turn, decreases our distance from them. It's interesting that even photos that deal in standard erotic poses, like Diana Scheunemann's two-page spread of a young model wearing only fishnet stockings, her legs kicking behind her while she poses belly-down on a brocade couch, don't seem hackneyed. We're aware of the overbright light in Scheunemann's shot, which allows us to glimpse the texture of the woodwork on the wall behind the model, and the fine hairs on her left forearm.

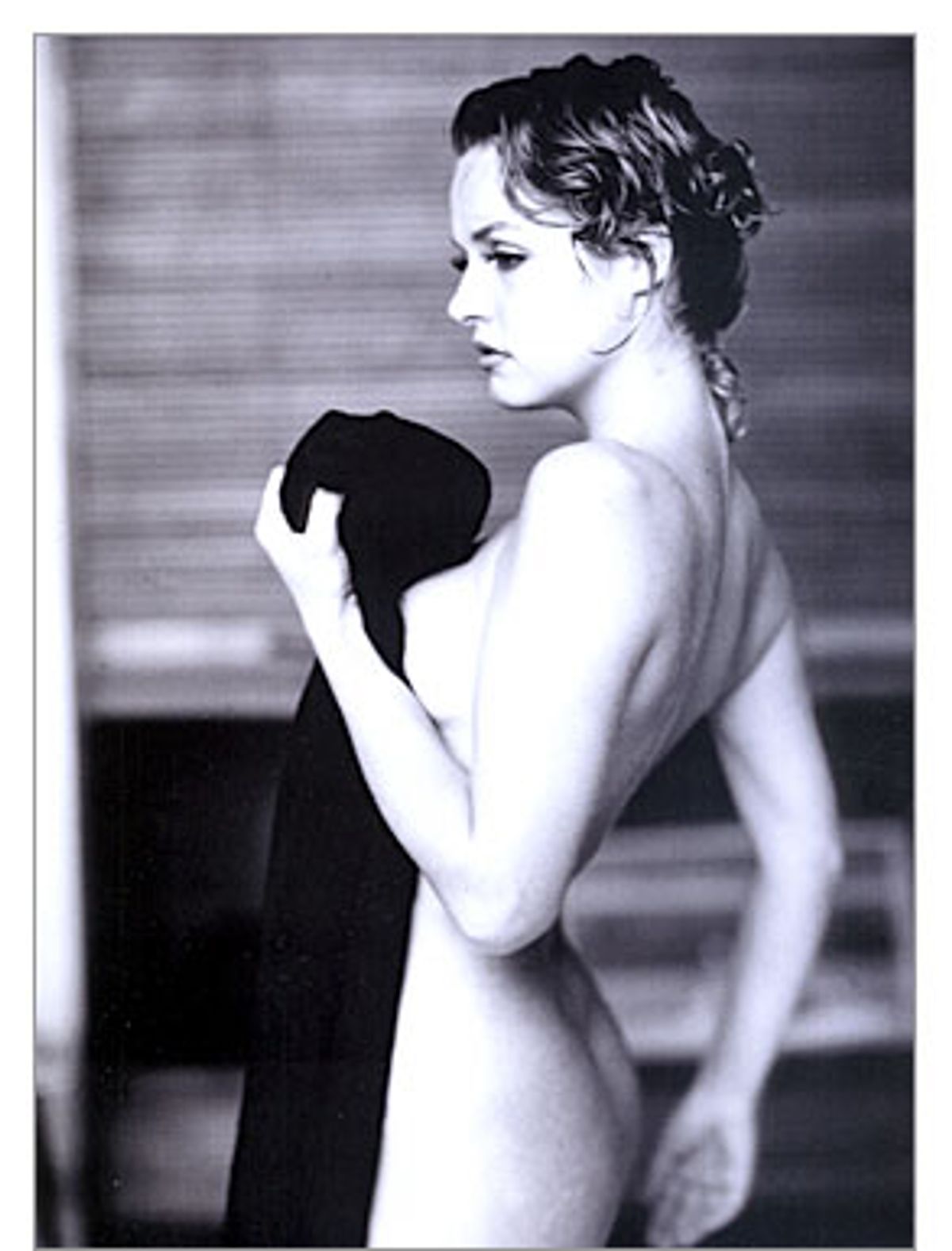

Of the work collected here, I was particularly drawn to that of Christine Kessler, who manages to give her photos a creamy look without an attendant slickness. She seems to have an intuitive eye for the smoothness of skin, particularly in one where a model stretches her nude torso out along a white bed while her hand trails into her black-and-white houndstooth check underwear. Kessler is attuned to the natural contours of the body. In the photo described above, the model's right arm, resting atop her torso, accentuates the natural line of her body, while a shot of a woman pushing herself up with her arms from a bed describes the smooth, pronounced curve of her back and the dip of her shoulders.

And despite my reservations about Hack and Kuhnen's introduction, one of the most pleasing -- and erotic -- aspects of the book is the way the photographers' cameras meet the gaze of their models. You can't even call these looks a provocation, though some of them -- Lori Mann's overhead shot of a full-breasted model, Francesca Galliani's striking photo of an Asian model sitting on a bare mattress, the bright-eyed gaze of the dark-haired model in the wonderful Ellen von Unwerth's trademark dreamy blur of a shot, and the cat's-eyed look of the young model in a shot by Melissa Ulto -- are deeply provocative. They seem more a confident statement of presence, a conscious presentation that says the model is in command of what the camera will see.

And maybe that's a clue to the ease of these photos, to the air of something very near to serenity that they impart. One of the photographers, Eliza Lazo DeSantos, says that when a woman is photographed by a woman there is "no undercurrent of sexual tension." That, of course, assumes both artist and model are straight. But the book is more a collaboration than a confrontation, a sense that female sexuality is understood by the people on both sides of the camera and can be taken for granted. The pleasure in the book, even in its most formalist photos, is the ease in its depiction of sexuality, its total inability to induce guilt, its telling us it's OK to both display and to look.

Shares