There’s a great scene in the movie “SLC Punk” that, if you want it to, can describe the entire arc of Radiohead, from shoulda-been one-hit wonder Britpop band to their current status (self-granted or otherwise) as the Most Important Band in the World. Two preteen geeks are hanging out one day after school in a basement den, deep in some moldy suburban home cut thick with cheesy paneling and the detritus of lonely and awkward youth: a game of Risk, stacks of comic books and Rush tapes.

As the two friends talk D&D and Risk, finally, one of them declares that he has found a new sound, and it has told him, like a thunderclap from the heavens, that so much of what they’ve been into all along has rendered them nearly unfit for pleasure, barely alive, unless you count life as an eternal sucker as living. With that, he pops the new tape in — why, it’s punk rock, of course — and begins carousing around the basement den, air guitar in hand as his buddy looks on in horror. When the sales pitch has ended, the friend stands up, and says matter-of-factly: “Now, what do you wanna go mess around with stuff like that for? I mean, you’ve got a good D&D character going and everything!”

Because for all their hip cachet and the lip service to experimentalism, darling, you know it’s true: Radiohead are the rock ‘n’ roll equivalent of the 12-sided die. They’re so square they have a square to spare.

Over the past few weeks — as you will for many more to come — you have been hearing ad nauseam about all the things that Radiohead are: representatives of a new generation of radicalism, an epic rock band of the like not seen since Pink Floyd, and the face of rock’s future. Well, here’s one thing they are not: cool. Scratch the surface of the group’s iPod mystique and you will find a dorkology that would make even the most hideously pony-tailed Rush fan blush. And yeah, “Hail to the Thief,” the group’s new album, is the apex of all that.

Despite that, the new record is a shoo-in for an alarmingly high Billboard chart showing, in part because, these days, Radiohead are the go-to guys for pop gravitas. Like Pink Floyd before them — it cannot be underestimated how the band has poached and then revised the Floyd formula for taking middle-class angst and launching it straight into the cosmos — Radiohead have become masters of radio dread, the ultimate existentialist rock stars.

Anyone who’s followed the band even casually will know that this is nothing new; even the band’s first hit, “Creep,” flailed around in its self-hatred, feeling guilty for even having a hook at all. But what’s new in all this is the sense that each new Radiohead album is issued as a state-of-affairs for all of the broken computer children of the world.

That all started three years ago with “Kid A” — the band’s long-awaited follow-up to 1997’s “OK Computer.” Hyped to high heaven as the virtual reinvention of rock itself, “Kid A,” more than being an actually great record, was a message record. Sonically bold and ambitious even beyond its own means (which is saying something — for all their future shock Radiohead are the very definition of a hard-working band), the album was meant to harness the band’s ever growing audience into making a statement to the world of commerce that, well, smart things can be popular too.

Miraculously, it worked. “Kid A,” you may recall, darted onto the Billboard charts at No. 1 — no small feat, in this day and age, for a British rock band enamored of experimental electronic egghead music and for a record with no real singles to speak of. Whether you liked Radiohead or not — I’ve always considered myself an impartial admirer of the band — watching “Kid A” have its way with the world was a thrill indeed. It was like seeing Ryuichi Sakamoto on Top of the Pops. You had the feeling that its very popularity was an act of insurgence. It felt good.

And it changed everything for the band. The “Kid A” affair inked a deal in blood between Radiohead and their fans that had mostly to do with the promise implicit in the sound of the album: Radiohead would no longer act like one of yesterday’s rock bands. No more songs about girls. Not so much with the guitars. And keep up all the Pink Floyd stuff, but be accessible — not so much in terms of the tunes, but more in the sense of, you know, updating your Web site frequently. More than anything else, be the voice of Internet generation: Be smart, be civil, be self-effacing and definitely, definitely be a little weird.

For the most part, the group was happy to oblige — it’s what Radiohead had been doing anyway, at least since “OK Computer” and arguably even before. In return, the band was granted a sense of Importance that has its only modern correlatives in bands like U2 or R.E.M. — bands who similarly melded the personal and political and had at least a passing power of radicalization over anyone who came into their paths.

Most bands who are bestowed with this honor eventually rebel against this status, of course — nobody really ever wants to be the conscience of their generation — and to that end, “Hail to the Thief” is a half-step back toward the door. There are guitars, drums and even a few girls. But if Radiohead are to renege on their covenant of Importance, they need to take a few parting shots on the way out, and “Hail to the Thief” all but comes with a sticker that reads, “Hi, we’re Radiohead, and we are still STICKING IT TO THE MAN!”

Like Moby, the band has worked overtime to subvert the typical jive that comes with rock ‘n’ roll superstardom: They go out of their way to be nice to fans and they intentionally get haircuts that make them look like a high school fencing team from Germany, circa 1974. Radiohead have strived to become rock ‘n’ roll eunuchs, desexualized and only as threatening as a nervy information-systems tech; they have exploited the anti-intellectualism that has been part of rock since forever and fashioned out of it something that, in the pop marketplace, is the closest we have to those two guys on the chess team that actually thought they were cooler than everyone else.

Part of this is a feat of willpower and determination — Radiohead have survived and even thrived in a pop marketplace that’s rapidly getting dumb and dumberer. But the band may also have inadvertently lowered its own expectations, simply by virtue of playing with the big boys and not walling itself in behind obscurity and brains (like some of the band’s obvious heroes, e.g., say, Autechre), and it’s this bit that is really the story of “Hail to the Thief.” The record doesn’t so much back off the freaky creed posited by “Kid A” and “Amnesiac” as it tempers those arguments. As with a lot of artistic compromises, few walk away happy.

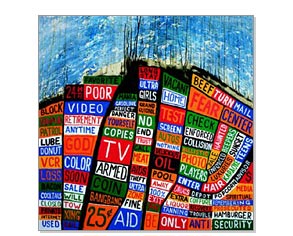

Much as the band has tried to downplay it in interviews, “Hail to the Thief” comes mired and wired into a code of new-school activism that almost makes it a full-on political event. And it’s a nice one: To kids all over the heartland that need it spelled out for them, the album’s cover art alone does a great job in getting the message across: The world is a scary and dangerous place, and yes, you should be nervous. Each day is minefield of anxieties, insults and small reliefs. But there is blue sky ahead if you want there to be. Insofar as “Kid A” announced to the pop world that — shock of shocks — there were people out there who’d had enough of artifice, “Hail to the Thief” raps on the same numbskull head and says that, duh, even rock ‘n’ rollers have better polemics than the Bushies these days.

Those arguments have resonated with a lot of people. Radiohead fans are loyal in the extreme, and this has left the band in a heap of trouble. “Hail to the Thief” is the sound of image-wrestling, and it ain’t an easy sport. There are quite a few quieter moments on this new record, but not a single one of them is relaxed, much less mellow. What you get instead is a pensive and pervasive angst that is modern and cold, conceptual and evolved, but in the end dismissive of itself: Radiohead are searching for a soul that they’re just a little too self-possessed to pull out without feeling like a bunch of cornballs.

This is to the great dismay of Thom Yorke, who sings the record like his life depends on it. Yorke’s high, roaming falsetto has been one of the signature rock moves of our time, and you can hear it now in an entire school of bands based at least in part on his and the late Jeff Buckley’s vocal gymnastics. On “Hail to the Thief,” Yorke does an amazing thing. He pulls these notes, these lyrical riffs that are ponderous and monolithic, and does so in such a way that not only is he not hamming, but he’s actually doing something new: In the grand tradition of soul music, he’s selling the songs.

But isn’t part of Radiohead’s whole deal this idea that there are no songs left to sell? Yes, and that’s the problem. “Hail to the Thief” revels in a sort of free-floating hooklessness; it’s music as object, sound as sound alone.

I won’t lie to you: Most of “Hail to the Thief” is pretentious jive. It shows the band grabbing at one oblique straw after another. On one hand, you have inverted piano ballads like “Punch Up at a Wedding,” which basically is a vamp on its title (it’s a good title, but there’s not enough song there), and on the other, out-and-out blippity scree like “Myxomatosis” that issues bass farts when it wants to be dangerous and accidentally lets great lyrics slip out when it’s meaning to be elliptical. “My thoughts are misguided and a little naive/ I twitch and I salivate like with myxomatosis” is as articulate an analysis of the Thom Yorke shtick as there’s ever been.

But “Hail to the Thief” is undeniably an event album. It almost doesn’t matter if it has great songs or not — almost. What people are excited by is the idea of Radiohead; it’s essentially an idea of progress, and for better or worse, the record moves on that considerable steam, once every few songs. “Scatterbrain” gets the gorgeous-ballad thing right. “A Wolf at the Door” finally delivers the fractured epic the band’s been promising all along. But again: In between, there are tracks like “The Gloaming” — barely songs at all, just chanted ideas. Good ideas, but whatever.

The best song by a country mile here is “There There,” which feels almost traditional in the shadow of “Myxomatosis” or the other glitchy numbers that abound. Over a raw guitar and snap-and-shimmy beat, Yorke bleats the lyric, “Just because you feel it doesn’t mean it’s there” over and over again in a way that finally marries monolith to melody. Suddenly, all those big, blocky, non-specific lyrics have an object to cling to: a lover, a friend, an ex, whoever. But the point is that it’s to somebody; I know that doesn’t sound like much, but after all the rigors of “Hail to the Thief’s” computer angst — which is essentially three albums’ worth at this point — feeling a real human presence in a song is quite something. It’s a particular stroke of genius, though, that the singer is trying to say it’s nothing more than a mirage, a hologram. When it all pays off in the last bunch of bars, breaks open in the way you know Radiohead, throughout the entire album, has been dying to, it offers one true moment of abandon. All this restraint has been killing these guys.

Try as I might, I can’t get “Hail to the Thief” to stick to me in any lasting or meaningful way. You could say that it’s because the band has finally perfected a form of music-making that lends itself to cold platitudes and leaves a color and shape instead of a tune. There’s nothing wrong with being a monolith. It’s not all about the single.

Does that sound like quantifying or consolation? It’s not. Radiohead are doing important things with music. It may be, however, that those things are not necessarily musical. And at the risk of sending Radiohead a booby prize, let’s just leave it at this:

Here’s to a band fighting its way out of a constituency’s expectations, at its own great peril — a band backing away from electronic experimentation into regular old rock ‘n’ roll, and retreating, ever so slightly, from a tremendous burden of expectation and responsibility. And here’s to a constituency that means so well toward its beloved that it may be reinventing the parameters of rock stardom. But both, at this point, ought to be mindful when considering the other, and remember what Jimmy Carter said of the powers that be when he was flying in the face of all that was short-sighted and shoddy: Don’t send them a message, send them a president.