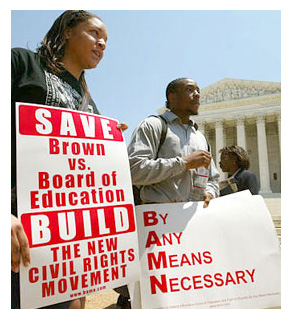

Racial discrimination turns out to be rather like pornography, in Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart’s famous formulation: We know it when we see it. The problem, as with pornography, is that everyone sees it differently. And the Supreme Court’s split decision on affirmative action Monday — upholding race as a factor in university admissions, but striking down a point system that gave blacks, Latinos and American Indians a significant advantage over whites and Asians — didn’t define the terrain any better.

Though they came 25 years apart, there are striking similarities between the Supreme Court’s Bakke decision and how it ruled Monday on the two University of Michigan cases. In both decisions the court endorsed the ends, but opposed the means, of systems designed to increase the numbers of “underrepresented minorities” in universities. In 1978 the court struck down the University of California quota system, after rejected white applicant Allen Bakke sued claiming racial discrimination, but it reversed a state court decision that said universities couldn’t use race at all as a factor in admissions. On Monday the court struck down the point system the University of Michigan used to boost minority undergraduate enrollment, but reaffirmed the core of Bakke — that it was fine for the university’s law school to use race as an admission factor, because it wasn’t a “predominant factor.” The record number of amicus briefs supporting affirmative action, from Fortune 500 CEOS to generals, showed that the American establishment clearly was not ready to take the momentous step of abolishing racial preferences altogether — and the key swing vote on the court wasn’t, either. Writing for the majority in the law school decision, Justice Sandra Day O’Connor explained: “Race-based action to further a compelling government interest does not violate the [Constitution’s] Equal Protection Clause so long as it is narrowly tailored to further that interest.”

And yet the court preserved the central ambiguity at the heart of Bakke: How much “race-based action” is too much? What does “narrowly tailored” mean? If quotas and point systems are forbidden, what sorts of measures are OK? By striking down Michigan’s point system, but upholding its much more opaque and subjective law school admissions process, which uses race as a “plus” factor, but won’t spell out how much, the court sent a confusing and disturbing message: You can continue to use race in admissions, but only if you don’t tell the public exactly how you’re using it.

O’Connor described the 1978 court as “splintered” and “fractured” by Bakke — the case resulted in six different written decisions, and none garnered a majority — and the twin University of Michigan decisions show it still is. It’s clear that on the question of race and racial preferences, the court reflects the divided nation whose legal system it presides over. It’s also clear that the courts have accepted the “diversity rationale” favored by Justice Lewis Powell in the Bakke decision — even though Powell was the only justice who took that position. In Bakke, the court was evenly split between liberals who backed racial preferences as a means to redress centuries of racial discrimination and lingering prejudice, and conservatives who thought preferences should be prohibited altogether. Powell took a somewhat idiosyncratic middle path, opposing quotas but finding that fostering student diversity was a compelling rationale for some sorts of racial preference in admissions. While striking down the U.C. quota plan, Powell wrote approvingly of Harvard University’s affirmative action plan, which used race merely as a plus factor, and as only one of many different markers of “diversity.”

Playing to Powell, even though he’s no longer on the court, the University of Michigan law school used “diversity,” not historic discrimination, as the main value driving its racial preferences. Considering race — flexibly — was necessary to admit the “critical mass” of minority students necessary to provide “the educational benefits that flow from a diverse student body,” the law school told the court. And a majority agreed.

The problem with the Powell doctrine is that it left the legal basis for finding diversity a “compelling state interest” quite vague. And Monday’s decision was even more vague. It was hard not to agree with the dissenting opinions arguing that the majority failed to apply the required “strict scrutiny” test for any system that uses racial classification. The court seemed to give the law school a pass on two key questions.

The first is exactly what “educational benefits” have been found to flow from diversity. The fact is that pretty much all of the studies that purport to show the educational advantages of a diverse educational experience are controversial; no study’s findings have been accepted across ideological lines. Certainly no one has proven increased academic achievement results from a diverse educational experience; at best the benefits are soft ones, like leadership skills and getting along with others. An even more disturbing question the majority opinion skirted is how the law school’s racial preferences, which are supposed to be “narrowly tailored” and “flexible,” manage to produce a near-identical outcome every year: The same proportion of blacks, Latinos and American Indians get into the law school as apply to it. When 9 percent of applicants are black, then 9 percent of the admitted law school class is black. When it dipped to 7.2 percent — voilà, so did the percentage of the admitted class. And law school admissions officials admitted they checked admission rates for underrepresented minorities daily as the process approached completion each year. (No one mentioned checking the stats for 40-something mothers of teenagers who own businesses, like Barbara Grutter, the woman who was denied admission and sued.)

Maybe most remarkably, it’s clear that Michigan’s law school’s “flexible” and “narrowly tailored” process results in as much disadvantage to whites and Asians as the undergraduate point system does. When you move beyond the very top tier of high-achieving students, of which virtually every applicant of every race is accepted, to the middle- and lower-achievement levels, almost no whites or Asians get into either school, while virtually all blacks, Latinos and American Indians do. In the tier of law school applicants that included Grutter — not quite the top tier, but still high — 100 percent of “underrepresented minority” applicants were admitted, but only 9 percent of comparable whites and Asians. At the undergraduate level, the point system meant that of the bottom third of applicants, no whites or Asians got into Michigan, but 9 of 10 blacks and Latinos did.

It’s hard not to think that if the law school were truly considering each applicant’s contribution to “diversity,” more than race, Barbara Grutter would have been a shoo-in. The average age of entering law school students is 24; she was 43. How many have run their own businesses? Raised two teenagers? Some kind of nagging inequity gave rise to her rejection, and to her lawsuit, and Monday’s Supreme Court decision will only lead to more of both. I write all of this as someone who, reluctantly, supports affirmative action as a necessary evil to right the wrongs of hundreds of years of racism. I also think the diversity argument is the wrong one to use to justify affirmative action. I wish Justice William Douglas’ rationale — “to remedy disadvantages cast on minorities by past racial prejudice” — had prevailed in Bakke. I think righting historic wrongs, and increasing the number of African-Americans and Latinos who are prepared for leadership, is worth some level of sacrifice on the part of the majority. But let’s be honest: It requires sacrifice.

The majority decision makes it sound as if we can have racial diversity on college campuses without anyone giving up anything — that we all enjoy the “educational benefits” diversity provides. The fact is, under both Michigan systems, deserving whites and Asians lose places to less academically prepared blacks and Latinos. I actually preferred the point system, perhaps tweaked a little — the 20 race-based points it awarded represented a full grade — to the law school’s mysterious process. The point system gives advantages to a wide range of applicants — 20 points to athletes and low-income students, six points to those from an “underrepresented Michigan county,” four points for children of alumni — and I think it was possible to come up with a fair set of points for race. (Meanwhile, point-system advantages for all those other groups still stand.)

The problem with all of these solutions, of course, is that no reliable marker exists for suffering and disadvantage. We all know “reverse discrimination” when we see it — when the wealthy child of privilege who happens to be black or Latino gets preference in college admissions over, say, a white third-generation welfare recipient. But the fact is, using proxies to get at race — like the programs the Bush administration supports, which allow the top students of every high school into state universities, as well as those that practice socioeconomic affirmative action — benefit far more white students than they do blacks or Latinos. Without affirmative action, the number of blacks at U.C.’s flagship Berkeley campus dropped 65 percent the first year, and four years later, after every kind of outreach, it’s still down 50 percent since the days of racial preferences. That’s why in the last few years several affirmative action critics, most notably Nathan Glazer and Jeffrey Rosen, have reversed their stands: because the only way to right the wrongs of racism is to pay attention to race.

There’s a corrosive effect to all the evasion and dissembling that’s required to minimize the role of race in admissions decisions. So I say let’s either do it right, and honestly, or not do it at all. But the Supreme Court wasn’t ready to make that leap. Monday’s decision was perfectly tailored to the times, if not the strict letter of the law. We’re not being honest with ourselves, collectively, when it comes to what we really think about race. Polls show Americans believe racism is still a problem, but we disagree on how bad a problem it is, and what should be done about it. Likewise, polls show we want our universities to be diverse, but we don’t like the use of race in admissions and hiring. And yet we know that without it, many elite institutions would be monoracial or nearly so: almost all white, or in California, all Asian and white. In short, we want diversity and genuine equal opportunity, but we don’t want to think about exactly how it should be achieved. The Supreme Court said that’s OK, for now. Here’s hoping we’ll be ready for more honest thinking soon.