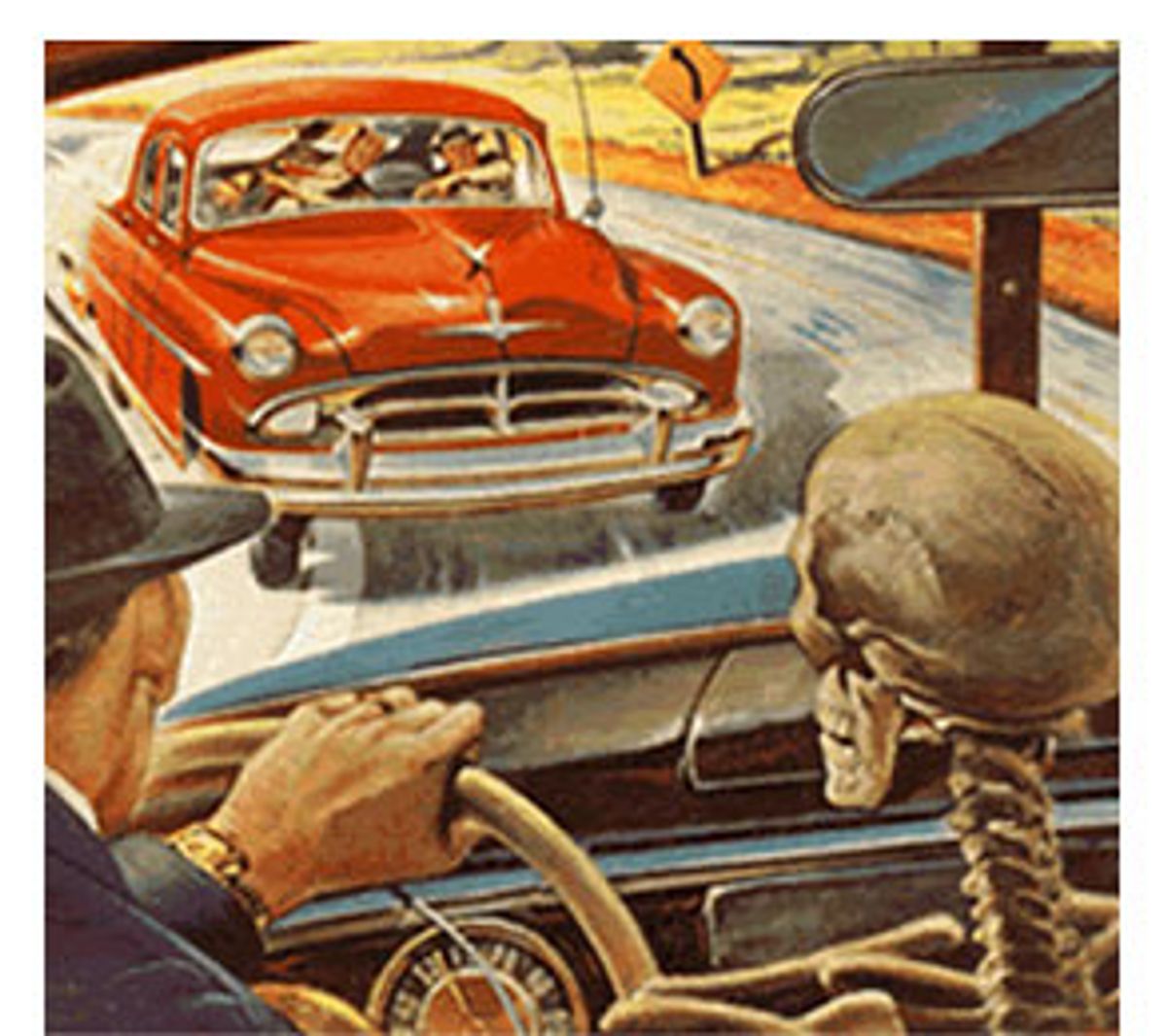

Starting in 1959, a small Ohio production company began producing a series of films that continue to enjoy a reputation (if "enjoy" is the proper word) as some of the goriest, most psychological-scar-inducing motion pictures ever made in the United States. Many of them had no plot whatsoever, instead consisting of one graphic, blood-soaked image after another -- hideous corpses, crushed and mutilated bodies, people screaming helplessly in nightmarish agony. These films were not marketed to the gore-movie enthusiasts who haunted the grind houses of Times Square and other seedy urban districts of the period. Rather, they had titles like "Wheels of Tragedy" and "Highways of Agony," and were widely distributed throughout the American high school system by a company called the Highway Safety Foundation.

"Any high school graduate from the mid-'60s to the late '70s probably would have seen them or heard of them," says filmmaker Bret Wood. His new documentary about the history of highway safety films, "Hell's Highway," opens this week in New York and Wichita, Kan. (with engagements in San Francisco, Cleveland, Portland, Ore., and Columbus, Ohio, to follow). By the time Wood himself attended high school, in the early '80s, the films of the HSF had been dropped from the curriculum, but he heard enough wild stories about them to pique his curiosity.

"There's a general disbelief that films like this could ever have been made -- especially for the classroom in the 1960s," he says. "I guess we all share a certain morbid fascination with them. When I was told about these films, I just assumed that people had misunderstood them. I didn't think they could actually have shown dead bodies. To me, that was just unthinkable -- I was really into horror movies and considered myself pretty sophisticated and jaded when it came to any kind of horrific images, and I figured it would be actors with ketchup on them.

"But when I finally got to see them," he continues, "it turned out all those kids I'd talked to were right! But it's not like these are just gore films on the level of 'Faces of Death'; there's something more to them because they're part of history, our cultural past. They're shocking in a way you wouldn't expect. A lot of people think it's just going to be massive amounts of blood. What's more shocking is that people are wearing recognizable clothes and they look like your parents' friends from when you were a kid. There's something familiar about them -- it's not Hollywood at all. It's shot on these two-lane highways in the middle of Ohio where the landscape is very ordinary and easy to relate to. You really get a sense of human loss and death that you don't get when you see a body blown up in a Hollywood movie. You can't relegate it to the world of make-believe."

As "Hell's Highway" points out, there was already a well-established tradition of educational films designed to reinforce positive social values and good citizenship before the Highway Safety Foundation came along. There was even a rich subgenre of cautionary tales aimed at teenagers about the dangers of reckless driving -- Wood even shows us a few moments from the legendary short "The Last Date," featuring a youthful Dick York (the original Darren from "Bewitched") as a cocky hot-rodder. What made the HSF's work so distinctive and powerful was its inclusion of actual documentary footage taken at crash sites; audiences got to see accident victims, blood coating their faces, still hunched over the driving wheel, hanging halfway out the car door or being lifted awkwardly onto stretchers. The camera would linger on the pools of blood staining the asphalt.

This grim aesthetic reflected the influence of the HSF's founder, an accountant and camera buff named Richard Wayman who, starting in 1954, began taking snapshots of accident sites in his spare time. Wayman never seemed to have gotten over a youthful infatuation with policemen, and his ghoulish hobby might have been his way of getting to hang around the men he idolized. Astonishingly, Wayman wasn't the only person in Ohio taking amateur photos of car crashes -- a woman named Phyllis Vaughn had a similar side interest, and before long she and Wayman had joined forces, delivering lectures and slide shows about highway safety to school groups and community organizations. Soon Vaughn's sister Dottie and a news photographer named John Domer joined the project and, in 1959, they produced their first motion picture, the legendary "Signal 30," with the assistance of the Ohio State Highway Patrol.

"'Signal 30' is the one that started it all," says Wood, "and because it's so crudely made it's probably the purest of the drivers' ed films. The more sophisticated they get, the less effective they are. There's one they made in 1966 called 'The Third Killer,' where they hired a Hollywood actor, Robert Diamond, to play Death. You see him go to the hospital and try to get people to die from cancer and heart disease, but medical progress causes people to live. So he thinks, 'How can I get people to die?' And finally he decides to go out and cause car accidents. It takes forever to get to the car wrecks, and by the time you do, you've had to put up with this hokey story. There's just something about the total lack of plot that makes the earlier, cruder films much more powerful.

"In fact," Wood continues, "I think if the actors in the reenactment scenes were really good, the films wouldn't work as well." Many of the films employed dramatic reenactments of the bad decisions -- teen drinking, late-night drag racing, etc. -- that purportedly led up to the real-life scenes of carnage. "There's something about the amateurishness of the whole production that gives them a sense of realism."

Wood has written several books about the history of horror films. He compares the way an unpolished film like "Signal 30" gets under the audience's skin to the impact of legendary low-budget '60s horror movies like Herk Harvey's "Carnival of Souls" or George A. Romero's "Night of the Living Dead." It doesn't seem like an accident that both Harvey and Romero got their directorial training while working for industrial film outfits in Kansas and Pennsylvania.

In "Hell's Highway," Wood interviews the two surviving members of the HSF creative team, John Domer and Earle Deems, and it's tough to reconcile this pair of ordinary-looking, mild-mannered seniors with the lurid films that made their company famous.

"They were really tough nuts to crack," says Wood. "I ask them what it felt like walking around in the middle of the night on this broken glass -- was the mood quiet and somber or were there sirens going, what did it smell like, what did it feel like -- and they'd just say, 'Well, I was too busy just trying to keep the picture focused.' I couldn't get any sort of feeling from them at all, much less explore the psychological foundation of the films or what effect they might be having on kids. I really couldn't get them to open up and talk about the deeper meaning of their films. They just seemed to think it was a strong safety message for kids and left it at that."

By the 1970s, the Highway Safety Foundation seemed poised to explode into the big time. The foundation had begun making a broad range of police training films (including an incredibly disturbing 1964 picture called "The Child Molester"), publishing safety pamphlets and brochures and even making plans to open driving academies in Ohio, New York, Florida and Pennsylvania. When Jimmy Hoffa testified before Congress in 1966 on the subject of highway safety, Time magazine ran a picture of him holding a print of the HSF production "Carrier or Killer." In 1973, Sammy Davis Jr. became the HSF's enthusiastic celebrity spokesman, allowing ghostwritten articles to appear under his name in newspapers across the country.

It was that association with Davis that helped sink the company, however. In May 1973, the singer agreed to round up a gang of his celebrity buddies (including Muhammad Ali, Paul Anka, Jerry Lewis, Rich Little, Mel Tillis and Ben Vereen) for a Highway Safety Foundation telethon. The telethon brought in $1.2 million in pledges, but the expense of putting it on stretched the HSF's resources to the breaking point, especially when Davis demanded that the foundation double the number of stations carrying the broadcast. When only $525,000 in actual pledges were collected, Wayman's company was left financially hobbled for the rest of the decade.

Wood feels the HSF's days were numbered, even if the telethon had been a success. "Within five years they would have had to change the types of films they were making," he says. "They made a couple of movies after the telethon, but the movement had definitely lost its steam and their style of educational film was definitely going out of favor. With the advent of video, schools had started junking their 16-millimeter prints and buying new educational materials. The stuff that was available on video tended to be the kinder, gentler types of drivers' ed films. All these 'death on the highway' films got shoved in the closet or just thrown away."

You can see how much times have changed, Wood says, by watching "Signal 30: Part II," which the Ohio Department of Public Safety produced in 2002. It abandons the HSF's trademark unflinching depictions of severed limbs and broken bodies and instead uses "Cops"-style digital blurring to shield audiences from any images they might find upsetting.

Wood has his doubts about the long-term effectiveness of the HSF's approach to driver safety -- he figures most people who saw its films probably drove more safely for a week -- but he does respect the eccentric integrity of Wayman and company's vision and the sincerity with which they went about expressing it. Wood's film honors that integrity by downplaying the camp value of these clumsy old movies and expressing an honest interest in this peculiar corner of American pop culture.

"I didn't want to trivialize what they were doing," Wood says. "And the last thing I wanted to do was make fun of seeing someone's dead body. It's very easy in our ironic age to poke fun at something and let it go at that. But there's more to these films than bad acting and gross-out images. I think they're powerful, creepy little films. Something happened here cinematically that was kind of ahead of its time, and you can't just laugh them off."

Shares