It is fitting that perhaps the seminal essay in defense of free speech in world history was written by the man the scholar Christopher Hill called "a more controversial figure than any other English poet." Heretic, revolutionary and supporter of regicide, outspoken defender of divorce, anti-Catholic, vitriolic political pamphleteer, John Milton was also one of the supreme poets in the English language, whose epic attempt to "justify the ways of God to man" has awed and given colossal headaches to generations of English majors trying to navigate the whitewater sublime of his syntax backward running.

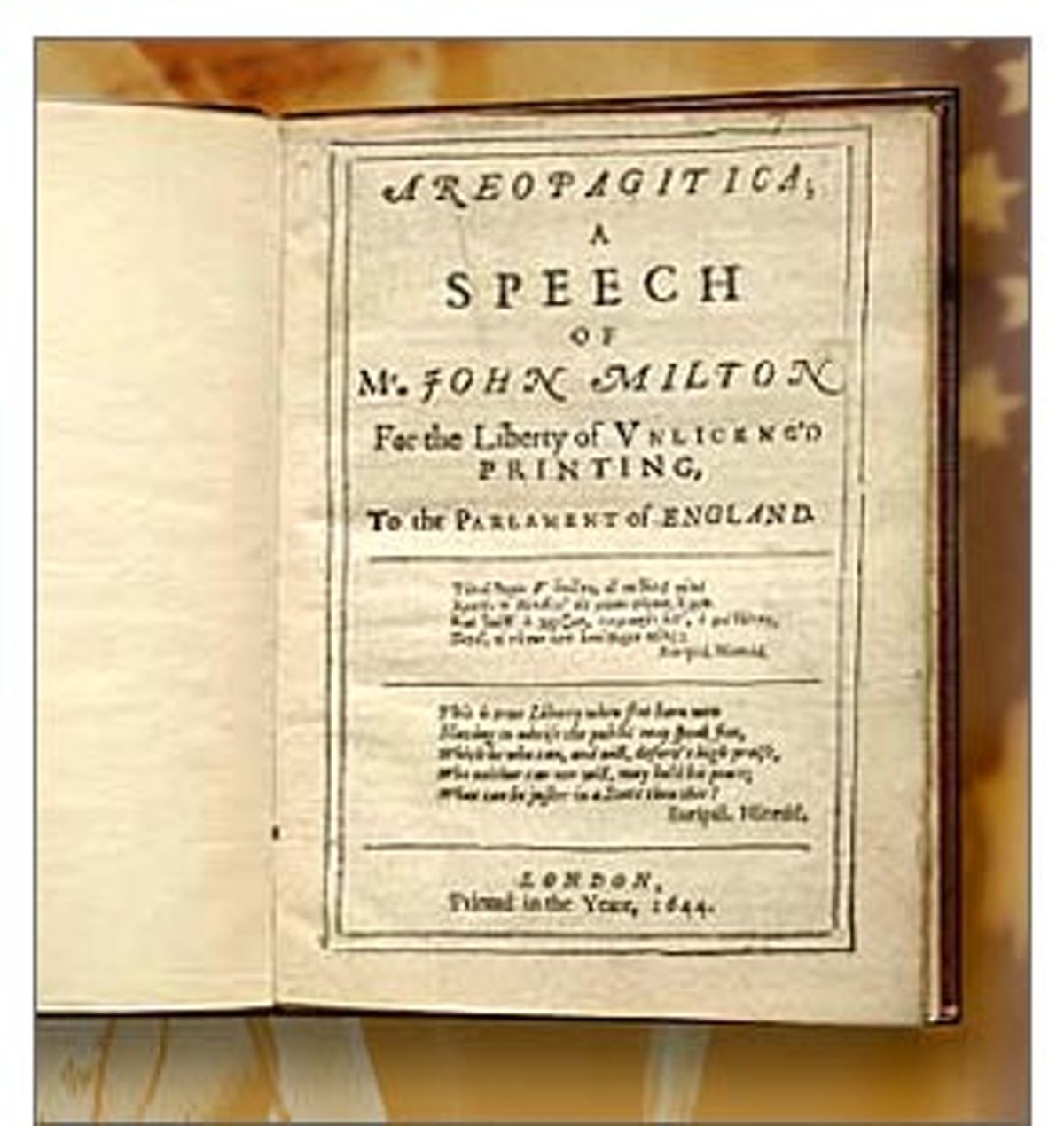

Three and a half centuries later, "Areopagitica: A speech for the liberty of unlicensed printing for the parliament of England" remains one of the greatest, most intricately argued and most eccentric free speech manifestoes ever written. It is not surprising that it inspired the American revolutionaries who created the Constitution and the Bill of Rights: "Areopagitica" was created during a unique (and, for Americans, underappreciated) time in world history, the English Revolution, when during a brief window of freedom and intoxication wild and woolly groups like the Diggers, the Levellers and the Ranters burst upon the scene, preaching whacked-out gospels that remain weirder than any ideologies dreamed up by the Beats or the hippies. As Hill observes in "Milton and the English Revolution," these "ideas had previously circulated only in the heretical underground: now they could suddenly be freely discussed. Milton celebrated this ferment in 'Areopagitica.'"

"Areopagitica" cannot be understood without some grasp of the turbulent times in which it was written. Milton wrote the tract in 1644, two years after the start of the English Civil War. In 1640 the heavy-handed and blundering King Charles I, who had refused to convene Parliament for 12 years, had finally been forced by financial necessity to call his legislators together. Following a series of royal missteps, culminating in his attempt to arrest five members for treason, Parliament turned against him and became the center of resistance to his rule. The struggle between the anti-Royalist Roundheads, led by Oliver Cromwell, and the Cavaliers ended in 1649, when Charles was executed for treason -- an event welcomed by the bitterly anti-royalist Milton.

The Parliament quickly abolished the infamous Star Chamber, a despotic secret court that Charles and earlier monarchs had used to persecute political enemies and the religiously heterodox -- and that also, through a monopolistic licensing system, controlled the publishing trade. The abolition of the Star Chamber and its licensing system led to a publishing explosion: The number of pamphlets published shot from 22 in 1640 to almost 2,000 in 1642. But when the war against Charles began to go badly in 1643, Parliament reinstated licensing, appointing a group of censors expert in various fields to pass judgment on printed material.

It was this return to state censorship in advance -- what we now call "prior restraint," the power famously rejected by the U.S. Supreme Court in the Pentagon Papers case -- that Milton attacked in "Areopagitica." Milton had his own reasons to be wary of censorship: He had been forced to publish his controversial tract on divorce without a license. But what gives "Areopagitica" its enduring power is the sheer height and breadth of its universal argument -- an impassioned defense of freedom and the human spirit. For Milton, writing at one of those hinge points in history when polemics take on the weight of the eternal, the two could not be separated.

The title of Milton's tract refers to the Areopagus, the highest court in Greece, to which the orator Isocrates delivered a speech calling for political reform: Isocrates attacked the judges for falling away from wisdom, just as Milton attacks Parliament for its folly in imposing censorship. This arcane classical elbow in the ribs of his readers is atypical, however. Milton starts by employing a double strategy: He deploys his prodigious classical learning to flatter and cajole his audience by invoking the greatness of the ancients, who rejected censorship; and he claims that it was the despised Catholics -- "those whom ye will be loath to own" -- who were the originators and greatest proponents of censorship. In effect, Milton is asking Parliament: Do you want to be like Pericles and his comrades, bestriding the earth like demigods, or do you prefer the bloodthirsty and superstitious papists, worshipping a corrupt bureaucracy and rejecting the Word of God?

The heart of Milton's argument, however, rises far above these stratagems. Bringing to bear his uniquely potent combination of Christian rigor and humanist freethinking -- a combination that in certain respects is alien to the modern mind, but in others is utterly contemporary -- Milton argues that all speech must be free, because it is only through struggle and competition that truth or religion worthy of the name will emerge. Speech must be free because man is free -- and man must be free because without freedom, there could have been no primordial Fall and there can be no future grace. "... what wisdom can there be to choose, what continence to forbear without the knowledge of evil? ... I cannot praise a fugitive and cloistered virtue, unexercised and unbreathed, that never sallies out and sees her adversary but slinks out of the race ... Assuredly we bring not innocence into the world, we bring impurity much rather; that which purifies us is trial, and trial is what is contrary."

Without vigorous and free debate, Milton writes, real thinking and real piety will wither away, to be replaced by mere mechanical, cowardly adherence to doctrine. Again, Milton contrasts Catholic submission to authority with manly Protestant independence. And again, he urges that God created a multitudinous world, and it is not for man to narrow its splendor. "No man who hath tasted learning but will confess the many ways of profiting by those who, not contented with stale receipts, are able to manage, and set forth new positions to the world. And were they but as the dust and cinders of our feet, so long as in that notion they may yet serve to polish and brighten the armoury of Truth, even for that respect they were not utterly to be cast away."

Moreover, Milton points out, it is the inevitable nature of censorship to muzzle writers whose genius is not immediately apparent. "But if they be of those whom God hath fitted for the special use of these times with eminent and ample gifts, and those perhaps neither among the priests nor among the pharisees, and we in the haste of a precipitant zeal shall make no distinction, but resolve to stop their mouths, because we fear they come with new and dangerous opinions, as we commonly forejudge them ere we understand them; no less than woe to us, while thinking thus to defend the Gospel, we are found the persecutors."

"Areopagitica" appeals not just to the vanity but to the patriotism of Parliament. Censorship, Milton maintains, is an insult to the intellect, spirit and integrity of the English people: "And it is a particular disesteem of every knowing person alive, and most injurious to the written labours and monuments of the dead, so to me it seems an undervaluing and vilifying of the whole nation. I cannot set so light by all the invention, the art, the wit, the grave and solid judgment which is in England, as that it can be comprehended in any twenty capacities how good soever, much less that it should not pass except their superintendence be over it, except it be sifted and strained with their strainers, that it should be uncurrent without their manual stamp. Truth and understanding are not such wares as to be monopolized and traded in by tickets and statutes and standards."

In one of "Areopagitica's" most famous passages, Milton compares his nation to a powerful man waking up from the long sleep of dogma and unfreedom -- and warns that censorship will send him back to his slumbers. "Methinks I see in my mind a noble and puissant nation rousing herself like a strong man after sleep, and shaking her invincible locks: methinks I see her as an eagle mewing her mighty youth, and kindling her undazzled eyes at the full midday beam; purging and unscaling her long-abused sight at the fountain itself of heavenly radiance; while the whole noise of timorous and flocking birds, with those also that love the twilight, flutter about, amazed at what she means, and in their envious gabble would prognosticate a year of sects and schisms. What would ye do then? should ye suppress all this flowery crop of knowledge and new light sprung up and yet springing daily in this city? Should ye set an oligarchy of twenty engrossers over it, to bring a famine upon our minds again, when we shall know nothing but what is measured to us by their bushel?"

Milton makes a powerful negative argument that the licensing laws are doomed to fail in any case, for corrupting and distracting elements are found everywhere in society. "If we think to regulate printing, thereby to rectify manners, we must regulate all recreation and pastimes, all that is delightful to man. No music must be heard, no song be set or sung, but what is grave and Doric. There must be licensing dancers, that no gesture, motion, or deportment be taught our youth but what by their allowance shall be thought honest; for such Plato was provided of. It will ask more than the work of twenty licensers to examine all the lutes, the violins, and the guitars in every house; they must not be suffered to prattle as they do, but must be licensed what they may say."

But perhaps Milton's crowning argument -- if not one that history has borne out -- is the notion that the truth will win out in the end. "Though all the winds of doctrine were let loose to play upon the earth, so Truth be in the field, we do injuriously by licensing and prohibiting to misdoubt her strength. Let her and Falsehood grapple; who ever knew Truth put to the worse in a free and open encounter?"

It seems to me that for Milton, freedom is an even higher virtue than Truth -- just as it is necessary that man be born free to choose his relationship with God, rather than born already saved and in the full light of grace. Even if he thought that Truth would not inevitably win out, Milton would choose a world of freedom.

Some critics have argued that Milton's position is far less tolerant than it appears, and that it is so nonsecular that it offers scant support for defenders of the First Amendment. It is true that Milton argues only against prior restraints on publishing: The authors of impious or libelous books, he makes clear, should be subjected to the harshest punishments. And it is equally true that Milton's tolerance is far from universal. His bitter attacks on "papists," and his refusal to extend his defense of free speech to Catholics, sits uneasily with modern readers. Within the context of his time and his beliefs, however, his views are hardly beyond the pale. Like all writers of his day, Milton was not a relativist willing to see the truth in all religions; nor did his notion of freedom extend to anything like modern limits. As a radical British Protestant in 1644, he believed that Catholicism was itself the unalterable foe of free thinking and therefore should be proscribed: For him, it occupied the place that incitement to violence or other unprotected speech does today.

There is no way to reconcile this latter belief with our modern notions of free speech: If Milton gets a pass here, it is purely on historical grounds. But the aggressive Christianity that drives Milton's defense of freedom seems to me eminently compatible with how we think about free speech today. Yes, his argument that the state must allow unfettered intellectual and spiritual inquiry is based on the pursuit of a truth that Milton, like all his contemporaries, defined in exclusively Christian terms (although eccentric ones). And yes, modern secular ideologies would probably be anathema to him. But the very intensity and paradoxical rigor of his Christianity seems to open it beyond itself: When Milton defends the search for truth, it is hard not to believe that deep in his soul, he would include as searchers many of those he might consciously reject. In short, at some level Milton is of the secular humanists' party without knowing it.

For all of its harsh edges -- or perhaps because of them -- "Areopagitica" remains more than relevant: In its reverence for the sacredness of writing and thought, it retains the power not only to inspire, but to make us ashamed. The truth is that books, the freedom to write, the freedom to think, mean very little to us anymore. A contemporary American cannot but feel a twinge of envious sadness when Azar Nafisi, the author of "Reading Lolita in Tehran," writes that for the women secretly studying literature in Iran, the works of Joyce and James held out the limitless promise of freedom.

Similarly, Milton's profound respect for books and for human thought as the quintessence and highest essence of humanity (a respect whose other side is intolerance) seems to come from a long-lost world. "For books are not absolutely dead things, but do contain a potency of life in them to be as active as that soul was whose progeny they are; nay, they do preserve as in a vial the purest efficacy and extraction of that living intellect that bred them." Nothing stronger has ever been written about the sanctity of books, or the human mind.

Shares