In the opening scene of "The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen," a tank plows through the elegant Victorian interiors of the Bank of England. In short order, we see the destruction of an inn in Kenya, an enormous book-lined London sitting room and the center of Venice, with the Basilica San Marco among the buildings reduced to rubble. This a destructo-thon for those with a taste for Old World elegance.

There's no reason why "The League of Extraordinary Gentleman" has to be as bad as it is, considering the inspired pop premise of its source, Alan Moore and Kevin O'Neill's graphic novel. The two installments that have appeared in book form so far are a sort of cold daydream of popular literature. Set at the end of the 19th century, the comics tell the story of a group of heroes assembled by British intelligence to fight various threats to the Empire. The ingenious element is that all of these adventurers are characters from popular fiction of the era. There's the aged Allan Quatermain (the adventurer from H. Rider Haggard's "King Solomon's Mines"); Mina Harker, née Murray (from "Dracula"); H.G. Wells' Invisible Man; Dr. Henry Jekyll and his alter ego Edward Hyde (who takes the form of a grotesque behemoth); and Captain Nemo (from Jules Verne's "Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea").

Their contact with the British government is an ancestor of James Bond and, as in the Bond books and movies, the head of British intelligence is M, and his initial is a hint at his own fictional identity. Moore and O'Neill use these characters to play a sophisticated version of the fantasies kids indulge in about whether Superman could defeat Spider-Man. The graphic novels are written and drawn in a style that mingles the formality of Victorian literature with contemporary raunch and bloodthirstiness. When Hyde goes on a rampage we get to see him ripping bad guys quite literally in two, or chomping on their limbs. The Invisible Man takes advantage of the sexual liberties open to a man who can't be seen. When Captain Nemo first welcomes Mina Harker aboard the Nautilus, he greets her with, "If I must have women on my ship, it is preferable they are alive, I think." Of the Egyptian mob pursuing her, he says, "A Mohammedan rabble, please leave them to me," before impaling them with an automatic spear gun. Nothing in the way these heroes do business is cricket, and that's the nasty fun of it.

You can't blame the screenwriters, James Dale Robinson, Don Murphy and Trevor Albert, or director Stephen Norrington for wanting to tone down the carnage -- and the coldness -- of Moore and O'Neill's comics for a big-screen adaptation. But would it have been too much to ask for them to come up with a script? It's likely that the contemporary mass audience isn't familiar with most of these characters (perhaps more familiar with Jekyll/Hyde and the Invisible Man than with Quatermain, Mina and Nemo) from either the novels that introduced them or the various movies made from those books. So the screenwriters squander a great opportunity to provide an entertaining back story about the characters' origins. Incredibly, they don't even bother to orchestrate the way these characters band together; we're denied the pleasure of seeing them function as a group, complementing each other's abilities (which, despite the tensions and distaste they feel for each other, happens in the comics).

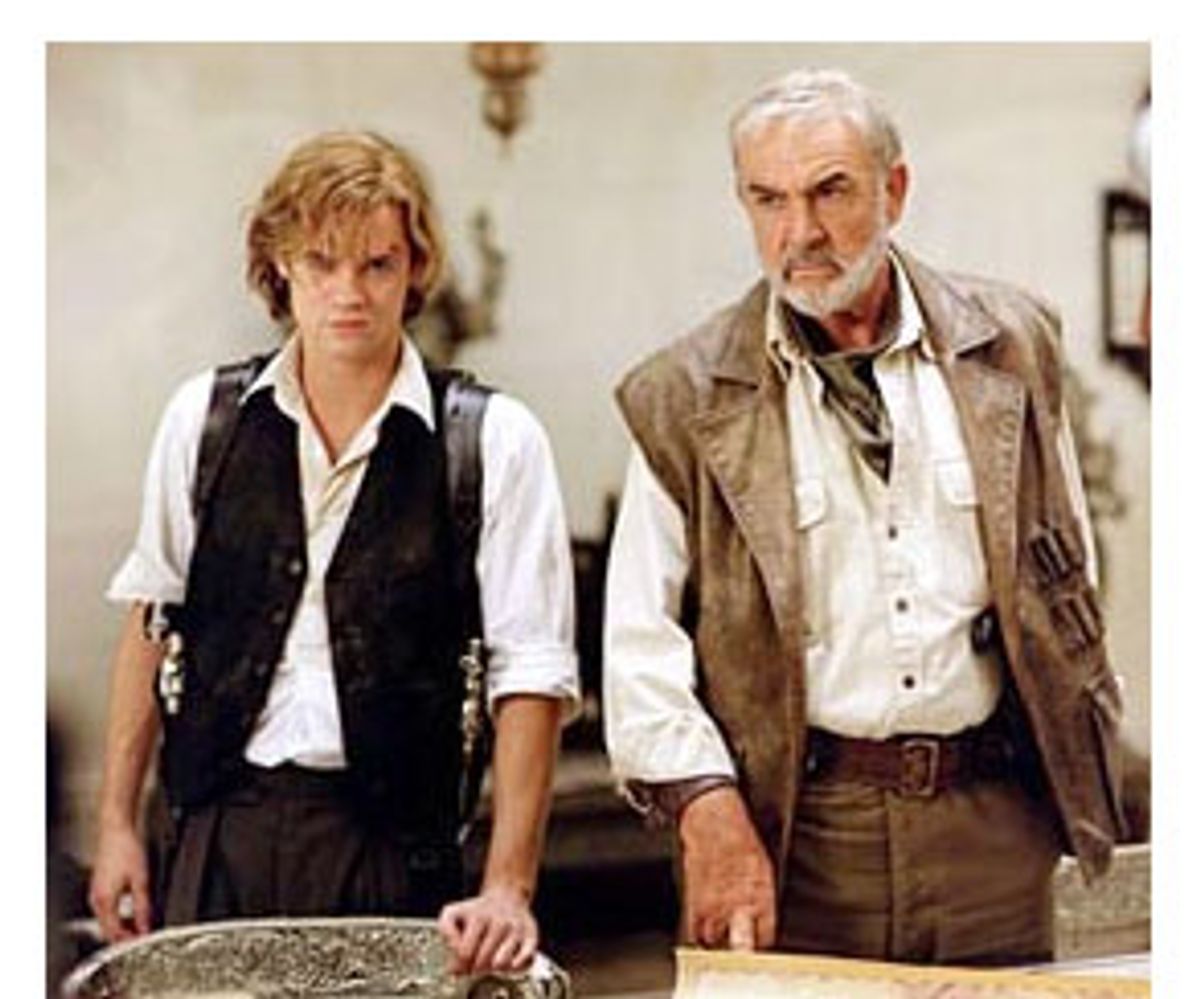

The movie is one blown opportunity after another. Sean Connery plays Quatermain (an improvement over Moore and O'Neill's depiction of him as a broken-down old opium addict) and when Richard Roxburgh (the duke in "Moulin Rouge") introduces himself to Connery as M, the filmmakers don't include a line or a joke to underscore the irony of James Bond meeting his boss's predecessor. The additions made to the cast of characters don't mesh well. At some point during a story conference, some exec must have decided that the movie needed an American character. But there are no lasting examples of action heroes from 19th century American literature. (They could hardly have had a tall cowboy type come in and introduce himself as the Virginian.) So we get Tom Sawyer as a United States Secret Service agent. It might have been witty if the movie had used the blank Shane West (who plays Sawyer) for a parody of American callowness set against European savoir-faire. As it is, he's nothing more than a Boy Scout along for the ride.

The screenwriters have also added Dorian Gray, a character, like Sawyer, outside the genre being celebrated. The role is an excuse for Stuart Townsend to ponce it up and act even more like an ambisexual rock star than he did as Lestat in "Queen of the Damned." Moore and O'Neill played with characters outside the adventure and "sensation" genres as well. At one point in their first volume we see a photo of an earlier League that included Natty Bumppo, Fanny Hill and Gulliver. But bits that tickle you in the comics, like Nemo's first mate introducing himself by saying "Call me Ishmael," fall flat here.

What passes for a plot here involves the League racing to Venice to stop a masked villain named the Fantom (the spelling probably a nod to Fantomas, the masked villain of the marvelous French pulp mysteries) from blowing up the city. But in the mode of summer blockbusters, our heroes seem to do as much damage to the city trying to stop the scheme as the bomb itself does. The work done by Norrington ("Blade") in the action scenes is the now sadly standard visual gibberish, loaded with the "what's happening?" confusion that film critic Mike D'Angelo has aptly labeled "spatial incoherence."

The look of the movie is a bit better. O'Neill's illustrations for the comics are fantastically detailed, a sort of fever dream of the 19th century (which makes up for Moore's macabre detachment). Carol Spier's production design and Dan Laustsen's photography capture some of that. The flattened perspectives do more to capture the look of comics than all of the multiframe busyness in which Ang Lee indulges in "The Hulk." Spier and Laustsen get an imposing, gray Victorian splendor, the somber, ominous color scheme suggesting an era on the cusp of the hellishness of the encroaching century.

The movie's most remarkable sight is our first glimpse of the gleaming Nautilus rising from the deep like an enormous silver blade cutting through the waters. (The least impressive is the cheesy Mr. Hyde, who looks like an action figure with a glandular disorder.) But we're given barely any time to look at anything, and Norrington can't invest the visuals with any discernible personality, or convey any pleasure in his concoction, so the look of the movie is both impressive and anonymous.

The cast has individual moments that suggest they might have been just fine with better material. David Hemmings shows up for one scene as an African drinking buddy of Quatermain's and, as he showed in "Last Orders," he hasn't a trace of vanity in him. I prefer this portly old devil with the flyaway eyebrows to the handsome young star of "Blow-Up" and "Camelot." Hemmings transmits a boozy likability from the moment you see him and you wish he stuck around longer. Connery isn't called on to do more than look strapping, which he could probably do napping in a hammock.

Naseeruddin Shah has a stately, imposing presence as Nemo. Tony Curran's Invisible Man has some of the giggling psycho flavor of Moore and O'Neill's character. And Peta Wilson has a nice sense of held-in menace as Mina. She benefits most from the movie's excesses. We get to see what the comics have only hinted at, the logical conclusion of her tangle with Dracula, though we don't get to see it often enough. (Sinking her fangs into some bad guy's throat becomes her, although it's impossible to tell whether the movie is consciously violating vampire lore by having her look into a mirror and go out in the sun or if it's just sloppy scripting.)

After this movie and "From Hell," Moore fans might start to take comfort that the movie version of his "Watchmen" has never come to fruition. His stories seem tailor-made for the movies, but his dark sensibility and the creepy pleasure he gets in playing with historical what-ifs don't fit with the mindlessness most mainstream blockbusters exhibit right now. The irony of "The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen" is that it has the most literate pedigree of any action movie you're likely to see this year or next -- and it's been made by people who seem to have no sense of how to tell a story.

Shares