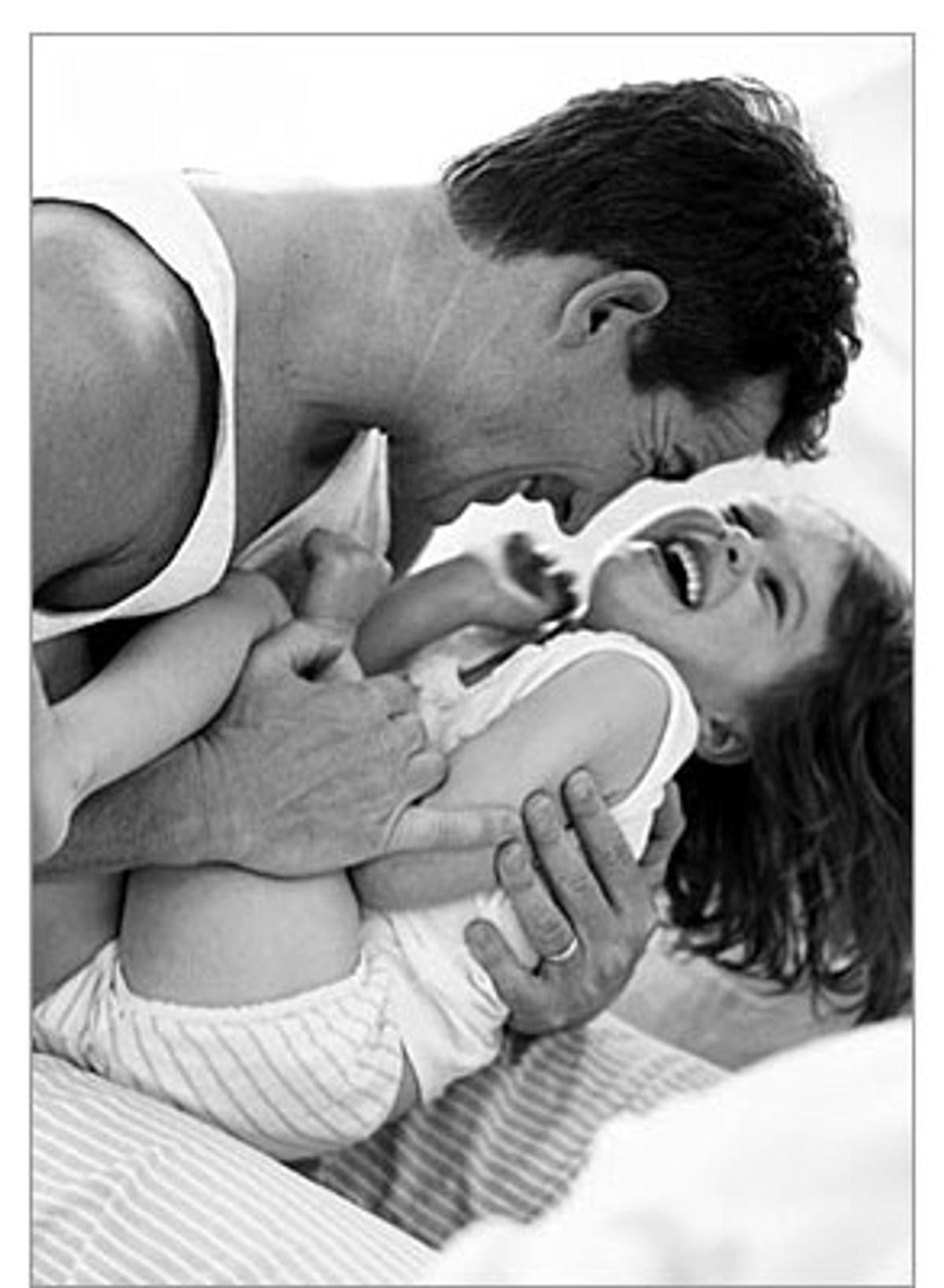

We have a daughter. But not really. She lives in our home, calls us Mommy and Daddy sometimes and gives us hard little hugs as she says, "I want to stay here forever!" She just turned 4 and has brown hair, brown eyes, a splash of freckles across her nose and cheeks. And any day now, she could be taken away forever.

Welcome to the world of fost-adopt.

Fost-adopt is a blending of the concepts of fostering and adoption. It exists in some form in every state. It came about under the Federal Adoption and Safe Families Act of 1997 to address the horror stories of children bounced for years from one foster home to another. Under fost-adopt, when the Department of Social Services removes a child due to serious neglect or abuse, it no longer places that child with just any home. Instead, the department identifies a fost-adopt-certified family who would be a good fit to adopt that child. This way if the birth parents lose their parental rights, the child is already in the home of the people who will adopt him or her. And if, instead, the child ends up going back to the birth parents, it's just too bad for the fost-adopt parents.

"We put the child first," the social workers told us in our orientation weekend. "That means you may be the ones who end up getting hurt. But better you than the child. You're adults. You can deal with it."

That was my first exposure to the strange mixture of tender and tough that characterizes the people working in Social Services. I quickly found them to be passionate about the children under their supervision while at the same time pulling no punches in describing a child's behavior problems or serious emotional issues. They worked long hours for little pay and somehow shrugged it off when the courts ignored their advice and sent children back into dangerous situations.

With very few exceptions, kids don't get pulled from homes unless there's egregious neglect or abuse. Not just spanking. Or being two hours late to pick your child up from day care. It's more like leaving your 3- and 6-year-old home alone for two weeks while you take a road trip with your new boyfriend. Or beating your children with a baseball bat. Or raping them. Repeatedly.

And yet children are amazingly resilient. We heard story after story of kids who thrived after being given a stable, loving home. The more we heard about fost-adopt, the more it seemed like the right thing for us. A chance to help a child in need, and at the same time a chance to create the family we desperately wanted and that infertility had denied us. We knew it wouldn't be easy; these kids brought a lot of emotional baggage with them. Most of them had PTSD (post-traumatic stress disorder). Many had RAD (reactive attachment disorder), an inability to connect with and trust other human beings. At RAD's worst, the symptoms are almost indistinguishable from those of a sociopath. They can include manipulative or overtly hostile behavior; lack of empathy, remorse, conscience or compassion; lying; stealing; and destruction, including of animals.

We also knew things might not work out with the first or even the second child we got. That's OK, we said. We'll take our chances.

There was one cautionary phrase, however, we heard from the other parents in the monthly fost-adopt support group meetings we attended as we waited for a child to become available. It would prove cruelly prophetic: "The legal stuff will drive you a lot crazier than the children ever will."

- - - - - - - - - - - -

Gina (not her real name) came to our home last December. She was 3 and a half. A bright-eyed pixie in a tiny western outfit, she proudly showed us her new "cow boots." We oohed and aahed and pinched ourselves. How could we be so lucky?

We'd first met Gina a few months before when her temporary foster family needed a baby sitter for the weekend. Shy at first, Gina warmed quickly to the attention we showered on her. She was playful, funny and curious. At dinner, she proved to be, as we had been warned, a picky eater. We decided not to make an issue of it and to keep things light and fun. I scooped up some pasta, made a funny face, slid the fork into my mouth and made an exaggerated swallow. She laughed and said, "Do it again."

I did it again.

"Do it again."

I did, but this time I said, "Why don't we do it together?"

She stared at me for a second as if she'd been slapped, dropped her head into her chest and slumped onto the floor in a heap. My wife, Jenny, and I looked at each other, shocked. Later we would come to recognize this behavior as something Gina did when she was ashamed or self-conscious. But at that moment, all we knew was we had a 3-year-old on our floor in the fetal position.

Jenny pushed back her chair and got down on the floor. She talked softly to Gina and soon Gina was curled up in her arms. Soon after, we asked Social Services to put us first in line as a fost-adopt home for Gina; three weeks later, she was placed with us.

The first few weeks only reinforced our belief that Gina was right for us and we were right for her. Without any other children in the home, we were free to give her our undivided attention. We helped build her lagging language skills by talking and talking with her. We played make-believe games, letting her be the leader in deciding who we each should be. We comforted her fears of monsters, storms and bad men. And every night at bedtime we whispered to her, "You're smart. You're pretty. You're funny (she always nodded proudly at this one). You're strong. You're a wonderful girl."

And she was. We delighted in her. We felt incredibly lucky, almost guilty. It was as if we had slipped into the system and plucked a perfect gem for ourselves. The other parents listened to us gush about Gina and said, "It's the honeymoon period. Just wait a couple of weeks."

We soon learned what they meant. Our happy, cooperative little angel began screaming bloody murder every night at bedtime. Her slump to the ground in a fetal position meltdowns increased and began happening in public. They could be triggered by the smallest thing, such as a gentle admonition: "Gina, please don't run." She became more picky at the table, refusing to eat anything but macaroni and cheese. She began stuttering. She rebelled at doing the simplest things, such as putting on pajamas or washing her hands before dinner.

"It's a good sign," said the caseworkers. "It says she feels safe enough with you to let her guard down. Just keep doing what you're doing. Keep adoring her. And keep giving her limits and structure. Especially when she's fighting you."

So we found ways to nurture Gina through her meltdowns without letting her behavior change the daily routine. We'd kneel beside her and say, "You're not in any trouble. We're not mad at you. We love you." Before long she would open her arms to be held and soothed. And she began to trust that we weren't going to abandon her or collapse in the face of a toddler power struggle. The meltdowns decreased. Bedtimes became easier. There was more laughter, more smiles, more play.

"We're doing it," Jenny whispered to me one night just before we fell asleep. Now the only thing we needed was for the court system to work its magic and make Gina available for us to adopt.

"I've got some news," said the caseworker. "We're postponing the termination hearing for three weeks." She went on to explain that Gina's birth mother had begun making progress on her treatment plan, and Social Services wanted to give her more time. "If nothing else, just to show the court we've given her every chance."

"No!" we wanted to scream. "She's already had her chance. Gina belongs with people who will protect and nurture her. Gina belongs with us."

How could we have let ourselves grow so complacent? We naively, perhaps stupidly, thought we were so perfect for Gina that no judge could possibly consider taking her away from us. Besides, with what we knew about Gina's past, and the kinds of traumas she'd been exposed to in her mother's home, what kind of thinking, feeling person would decide to put her back in harm's way?

It would be so much easier to tell this story if I could share the details of Gina's early life and what had caused her to be taken from her home. It would make it much simpler to get across why we (and everyone who has worked with Gina) feel so strongly she should never go back there. But, as foster parents, we are legally required to keep all those details confidential. Social Services required us to sign a legal form to that effect. All I can say is that when I first heard the details myself, I felt sick to my stomach and very angry at the kinds of pain and abuse little kids can suffer.

The anxiety during this period was more than I had ever felt before. I found myself lying in the dark imagining handing Gina back to the home that had so failed her before. I pictured her calling for help and not being able to comfort her.

As if to make the stakes even clearer, Gina began speaking of her experiences in her old home. Horrifying little stories told in a matter-of-fact voice. One day at the park she dragged me onto the play structure with her, crawled into my lap and whispered, "Keep me safe." "Yes," I said, blinking back tears, "I will."

- - - - - - - - - - - -

The termination of parental rights hearing was my first experience in a real courtroom. I was not prepared for the horrible sense of helplessness I felt, sitting in the back. The prosecution asked questions, witnesses testified, the defense objected. The judge, a grandfatherly presence, presided over everything in a calm, rational voice. I wanted to scream.

At first things seemed to go our way as the expert witnesses testified that Gina's mom wasn't psychologically capable of caring for her. Then things would swing back toward Gina's mother, as she produced church friends who said they would trust her with their own children. Of course, when I say "our way" I'm engaging in the comforting fiction that we had any place in the proceeding. Legally, it was a matter between the county and the birth mother alone. The issue before the court was simply whether or not she met the standard to keep her child. And that standard was purposefully minimal because the state does not want to take kids from their birth parents except as a last resort. All Gina's mother needed to do was convince the court she could provide a basic level of protection and care for her child.

Her lawyer did his best to make that case. He insisted Gina's mom was doing everything Social Services had asked of her, such as getting counseling, attending school, working with a family therapist. "This is a mother who is working hard. She's making progress. She admits she made mistakes in the past, but she's working hard to change. It would be cruel and unfair to punish her by taking her daughter away."

Cruel and unfair? As if a child were a reward to be handed out. The law says in termination cases the foremost concern is the welfare of the child. I prayed that the judge would keep that in mind and not be swayed by the defense attorney's emotional argument.

The prosecution responded by admitting that, yes, Gina's mother had done all these things, but she still had a long way to go before she could be a minimally adequate parent, specially for a child as young as Gina.

Termination of parental rights is the family court equivalent of the death penalty. Next to taking someone's life, taking a child away forever is the most devastating thing society can do. For this reason, judges do not like these cases and they terminate with great reluctance. In general I agree with that, but not in this case. Not with Gina. Not with the horrors that had occurred in her home. Social Services reassured us that it had a strong case, but in the end it would all come down to the judge. I comforted myself with the mantra, "Soon we'll know."

Wrong again. At the end of the trial, the judge addressed the court, "This is a difficult case and I've got a difficult decision to make. So I'm going to take it under advisement for a week or two before I make my ruling."

That was nine weeks ago. And no one can offer us a reason for the delay. We keep waiting for word that a verdict has been reached -- an answer that refuses to come.

- - - - - - - - - - - -

This afternoon I took Gina swimming at the local public pool. It's her favorite thing to do, and it's become a staple of our developing father-daughter relationship. She loves to throw the beach ball back and forth and to jump from the side of the pool into my arms. Sometimes she curls up in my arms and says, "Hold me like a baby." So I do while reassuring her that I love her as a baby or a big girl or whatever she wants to be.

The legal stuff will drive you a lot crazier than the children ever will. I feel crazy. Riddled with anxiety, distracted, I weep when I'm alone. Waiting for the shoe to drop. Only, of course, it's not a shoe; it's a vulnerable child I've come to love in a way I've never loved before.

"I love you and you," Gina says, pointing first to Jenny and then to me as we tuck her into bed. "You take care of me forever?"

I ache because I have no answer for her.

So I say, "You're smart. You're pretty. You're funny. You're strong. You're a wonderful girl." Then I pull the covers up, and kiss her forehead goodnight.

Shares