At the George Orwell centenary conference at Wellesley College in May, I began a short talk by quoting perhaps the most boring piece of writing by Orwell that I know:

"I like praising things, when there is anything to praise, and I would like here to write a few lines -- they have to be retrospective, unfortunately -- in praise of the Woolworth's Rose.

"In the good days when nothing in Woolworth's cost over sixpence, one of their best lines was their rose bushes. They were always very young plants, but they came into bloom in their second year, and I don't think I ever had one die on me. Their chief interest was that they were never, or very seldom, what they claimed to be on their labels. One that I bought for a Dorothy Perkins turned out to be a beautiful little white rose with a yellow heart, one of the finest ramblers I have ever seen. A polyantha rose labelled yellow turned out to be deep red. Another, bought for an Albertine, was like an Albertine, but more double, and gave astonishing masses of blossom. These roses had all the interest of a surprise packet, and there was always the chance that you might happen upon a new variety which you would have the right to name John Smithii or something of that kind."

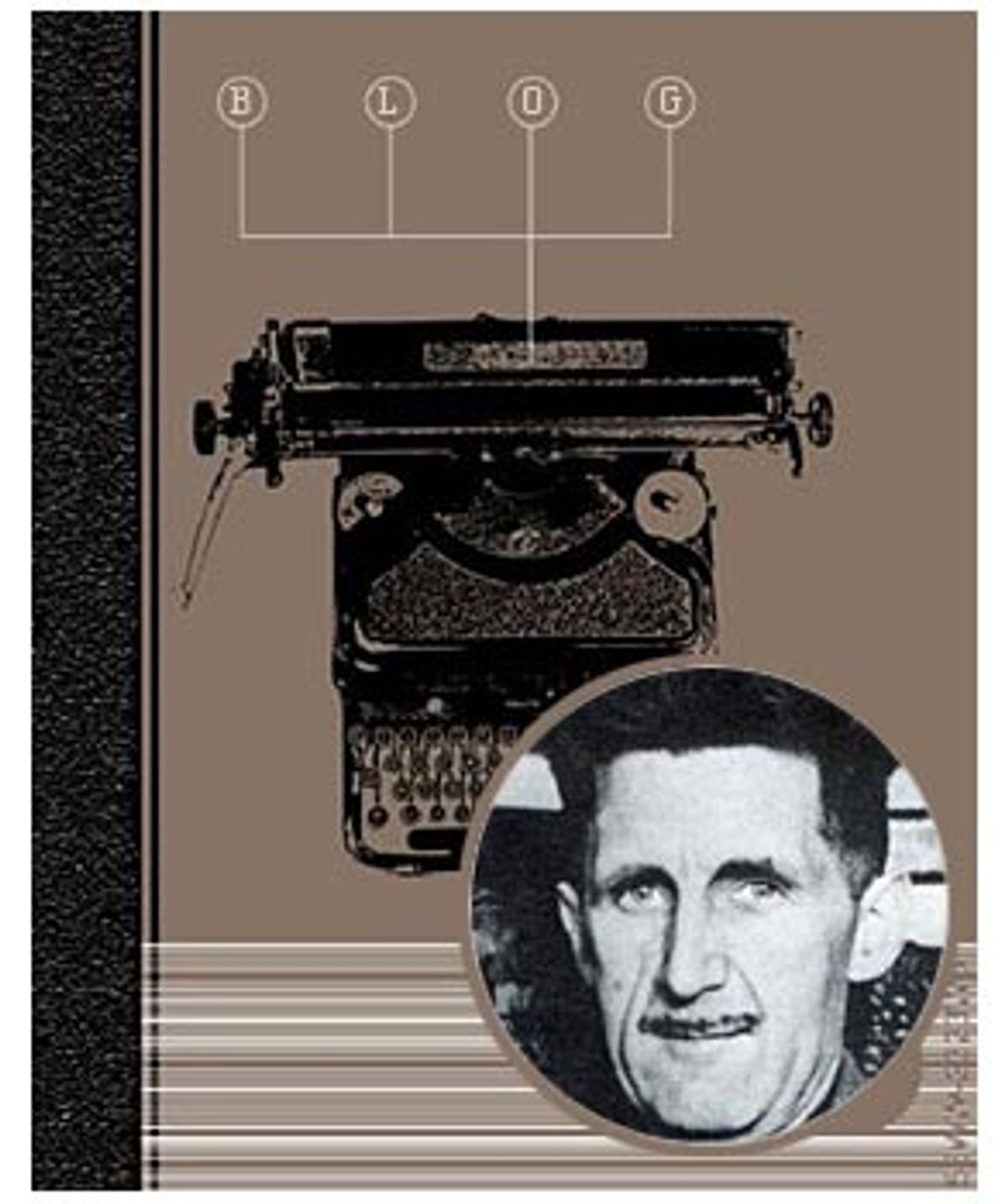

At the conference, I was standing in for Andrew Sullivan, one of the more prominent pioneers of the Internet weblog. That, and the short notice -- two days -- may explain how I made the connection between Sullivan and Orwell, whom one could call a proto-blogger of sorts: Orwell specialized in much the same sort of running political and social commentary as Sullivan in a wartime Tribune column known as "As I Please."

Although not Orwell's invention -- Michael Shelden's biography tells us that Tribune editor Raymond Postgate called his own 1939 column "I Write As I Please" -- this phrase has seemed to me for a long time now the blogger's credo, for most bloggers are not of the level of Sullivan or Mickey Kaus but are bores and cranks and, one would think, only a bore could call his site "As I Please," with its suggestions of windy self-satisfaction, tedious opinions on everything, and the lack of a firm editorial or restraining hand.

The blogger assumes his every spittle is of the greatest import, for why else share the daily meanderings of his mind? In fairness it is a question we should ask Orwell. Does the blogger's rose-buying adventure, even if it is George Orwell doing the buying and beforehand the sniffing, merit our attention? The excerpt above ends with an anecdote about two roses Orwell planted in 1936 that cost him sixpence; now it is "a huge vigorous," and beautiful, bush: all for the price of ten cigarettes, or a pint and a half at the pub, or a week's subscription to the Daily Mail: one of Orwell's little lists. Are we so desperate for Orwell trivia and "sweepings," as E.M. Forster put it, in the same way we are for Shakespeare's or -- the other iconic mid-century writer -- Hemingway's?

The answer seems to be yes; certainly his biographers Crick, Shelden and Meyers seem to feel so. But what does that mean for readers of present-day bloggers? First we have to weed out those readers who claim no interest in literature or even language: a significant number, one would think, among politicos; and we can measure this by how badly written, ungrammatical, actually, many of these political weblogs are. (This includes the very amusing Mickey Kaus of Slate.) They will be happy with the news or spin of their favored blog the minute it comes out; others might wonder how these things will read months or years later. Will the blog prove as enduring as that 18th century invention, the essay?

Perhaps. First, let us consider just how "As I Please," or as it would now be, As_I_Please.com, anticipates the modern weblog. For one thing, there are the "links" (not clickable) to recently published articles and other small pieces of forgettable or perishable journalism. No. 23 "links" to a book where poetry snobs can test their knowledge, and probably embarrass themselves; No. 27 "links" to a passage from Herodotus about Babylonian wedding customs, inspired by something Orwell has read about 1940s personal ads. Andrew Sullivan frequently links to what he dubs offensive cartoons or photos; Orwell does the same in No. 41, to a photo of shaven-headed Parisian women accused of collaboration that was printed in the Star, he says, ten days before. And in No. 48, a reader sends in his own link, to a cheap Tory pamphlet he presumes, rightly, that Orwell will find offensive.

A blog is also a place to respond to attacks made elsewhere, and there is some of this too in "As I Please." Most blogs recommend books, or unrecommend them as the case may be, or focus on certain passages usually of nonsense. Orwell does this to Bernard Shaw, for instance. Sullivan waged a near-daily campaign against the Howell Raines New York Times for over a year, and much of "As I Please," while not focusing on any one paper as its target, is a relentless and unsettled eye on the London press. Most of all, in blogs, there is an interest in provoking and sometimes baiting readers, who then write in to (e-mail) the paper (the site) with their outbursts of indignation or scorn or disbelief or supplication.

Orwell wrote 80 "As I Please" columns between Dec. 3, 1943, and April 4, 1947 -- all but the last 21 during the war -- and nearly a third of them respond to readers' questions or thoughts or complaints. The boring excerpt above, from "As I Please" No. 8, begins: "A correspondent reproaches me with being 'negative' and 'always attacking things.' The fact is we that we live in a time when causes for rejoicing are not numerous." Thus Orwell's ironic concession to his reader: Indeed he has something to praise and will spend two lengthy and tedious paragraphs doing so. Ultimately a blogger's domain is the paragraph, and just as blogs are really no more than a collection of often unrelated paragraphs posted each day, so "As I Please" is each week three or four long paragraphs on two or three subjects; it is never an entire essay, with exposition from start to end. It plunges us in without preliminaries, and ends only with the next day's, or week's, or hour's, post. In short, it is continuous, which the essay never is.

For that Orwell conference the first weekend of May, and my last-minute talk, I had to read all 80 "As I Please" columns in a period of two days. The timing turned out to be more opportune than I had expected. If I had read them a month or more before, just before the Iraq war, the echoes would not have resonated, only faded within the walls of an empty room. Beyond well-fed, well-paid American soldiers carrying about the place, the following all surface in Orwell's first 40 or so columns: tense British-U.S. relations although allies, "unsinkable" military experts wrong in their predictions, air bombing and bomb shelters, the faults and problems inherent in the BBC, the writing of history, "the freedom for which we are fighting," Jews and anti-Semitism, maps and politics, a well-informed citizenry, or not, and its right to influence policy, postwar redevelopment of a damaged country (the U.K., not Germany), punishing collaborators and war criminals, postwar policy toward the vanquished enemy, vulgar newspapers becoming temporarily serious but also, in Orwell's words, "reticent," gas and other weapons, pilotless planes, millions of irreplaceable books disappearing in the Blitz and emptied libraries, psychological operations, human or civilian shields, and provisioning the capital.

This is London, of course, not defeated Berlin; and the wartime "As I Please's" have very much a London or metropolitan tone to them. Harold Pinter, who for all we know may have learned something about terror from Winston Smith, is not the first writer to be obsessed with London bus routes; in No. 5 there is Orwell on the 53 bus, despising the "hideous war memorial" that blocks the facade of a Regency church across the road from Lord's cricket ground.

What is the importance of any of this to us now? Then, of course, it would have been important, in the sense that any opinion-writing in an intelligent magazine read by intelligent people is important; and it's not as though Orwell is slumming with these pieces. They are hack work like any regular journalism, but they are distinguished hack work, and often playful or witty, and certainly highly observant, which is another way of saying they're intelligent. If you like Orwell for himself, the man you think he is, he is an attractive figure in these pages, and for biographers, who must have everything a man writes, "As I Please" is indispensable. Same too for those who have an agenda, and most people who claim Orwell have an agenda. If it's important that Orwell be sound on the Jews, he is: Some of his most robust writing against anti-Semitism can be found here. If you believe your country should welcome large numbers of refugees or immigrants with no impediment to race or ethnic background, you will be heartened to read Orwell encouraging whole-scale immigration to the U.K. in No. 61, of November 1946. In short, if you want to like Orwell as you do your friends, dipping into "As I Please" humanizes or relaxes him, but some of us don't want our important writers in a relaxed mode. We prefer the urgency, the concentration.

Judged as literature -- and why shouldn't it be? -- or at the very least belles-lettres, the blog on its own is insufficient unless a prelude to greater things, and in Orwell's case the better stuff to come, first worked out in some aspect beforehand in "As I Please," includes the landmark essays "You and the Atom Bomb," "The Prevention of Literature" and "Politics and the English Language." ("Looking Back on the Spanish War" is the reverse: the great essay preceding its shallower echoes in "As I Please.")

In the last few months, we've been told that Iraq: The Second Coming is the first bloggers' war, that bloggers brought down the leadership of the New York Times; and even before that, in 2000, we were told that bloggers had started to change our election campaigns: first evidence of this being the midterm elections last fall, the most decisive evidence still to come in the presidential year 2004. All of which may be true, but beside the point. The bloggers' aim is the immediate response, and first thoughts are seldom the sharpest; rough drafts are never read except by scholars and pedants. If Orwell's blogs are readable now yet not especially interesting, it tells us how lesser writers like the rest of us will appear in the decades to come. Any writer worthy of the name (now there's an Orwell generalization for you) wonders about his legacy, how foolish or sensible or eloquent he will seem after he is gone. The best record of a writing life is on paper, collected into volumes that are then printed; in that way does the essay survive, whereas we don't know yet how the weblog will.

Shares