When Sgt. Micheal Dooley, 23, shipped out from Fort Carson, Colo., to Iraq on April 11, his wife, Christine, began taking the phone to bed with her. Around 3 a.m. every Monday, Micheal would call without fail. The connection could be frustrating -- a few seconds delay followed every sentence, and sometimes there were so many soldiers waiting in line to call home that Micheal could only talk for five minutes -- but still, Christine lived for those calls. They were her only connection to her new husband. She wanted to know everything about what Micheal's unit, the 3rd Armored Cavalry Regiment, was doing and seeing in Iraq, but he always managed to steer the conversation back to Christine, who is due to give birth to their first child -- a son -- in October. Was she having morning sickness? Was her belly growing? Did she feel tired? He told Christine that he kissed photos of her and their baby's ultrasound every night before he went to sleep.

On Sunday, June 8, Christine took the phone to bed with her as usual, but it never rang. Instead of her weekly conversation with Micheal, Christine had vivid dreams of him instead. She dreamt of the things he would do when he returned home: renovating the deck on the house they'd recently bought, taking their two dogs -- a cocker spaniel and a boxer -- to a nearby dog park, painting their baby's room. "Normal life things," she says. The dreams were peaceful, the sleep the best Christine had had in weeks. So much so that when there was a knock on the front door just past noon the next day, Christine was still in bed. She felt sick to her stomach, and slowly got dressed. When Christine opened the door, an Army major informed her that her husband was dead. "I didn't feel anything, I was just numb," she says. "Part of me was hoping that it was a joke. I knew it wasn't, but I was hoping."

Since May 1, when President Bush landed on the deck of the USS Abraham Lincoln and triumphantly declared the end to "major combat operations" in Iraq, 93 soldiers have been killed there, including nine in the past week alone. While the White House struggles to convince an increasingly concerned public that ongoing military operations in Iraq are worth both the human and monetary costs, people like Christine Dooley are left to mourn the loss of loved ones -- and wonder whether they died in vain.

Like many soldiers who have fallen in the three months since the official end of the war, Micheal Dooley's death was not combat-related. On June 8, while working security at a traffic checkpoint in western Iraq, near the Syrian border, Micheal was ambushed by three Iraqis who claimed to need immediate medical attention. When Micheal approached their car to offer help, he was shot at the base of his skull. Two of his assailants were killed by American soldiers, and the other escaped. "I've been told he went quickly," Christine says. "I don't know what I'd do if he had suffered like some soldiers I've heard about."

Born Feb. 2, 1980, to a 16-year-old struggling single mother in Pulaski, Va., Micheal was the quintessential all-American kid who played baseball and basketball, loved Nintendo, and rode a skateboard. He had a wide, open smile and "couldn't say no to anyone," says his mother, Ann Davis, 40, who speaks in a honeyed Southern drawl. "He'd give a stranger the shirt off his back."

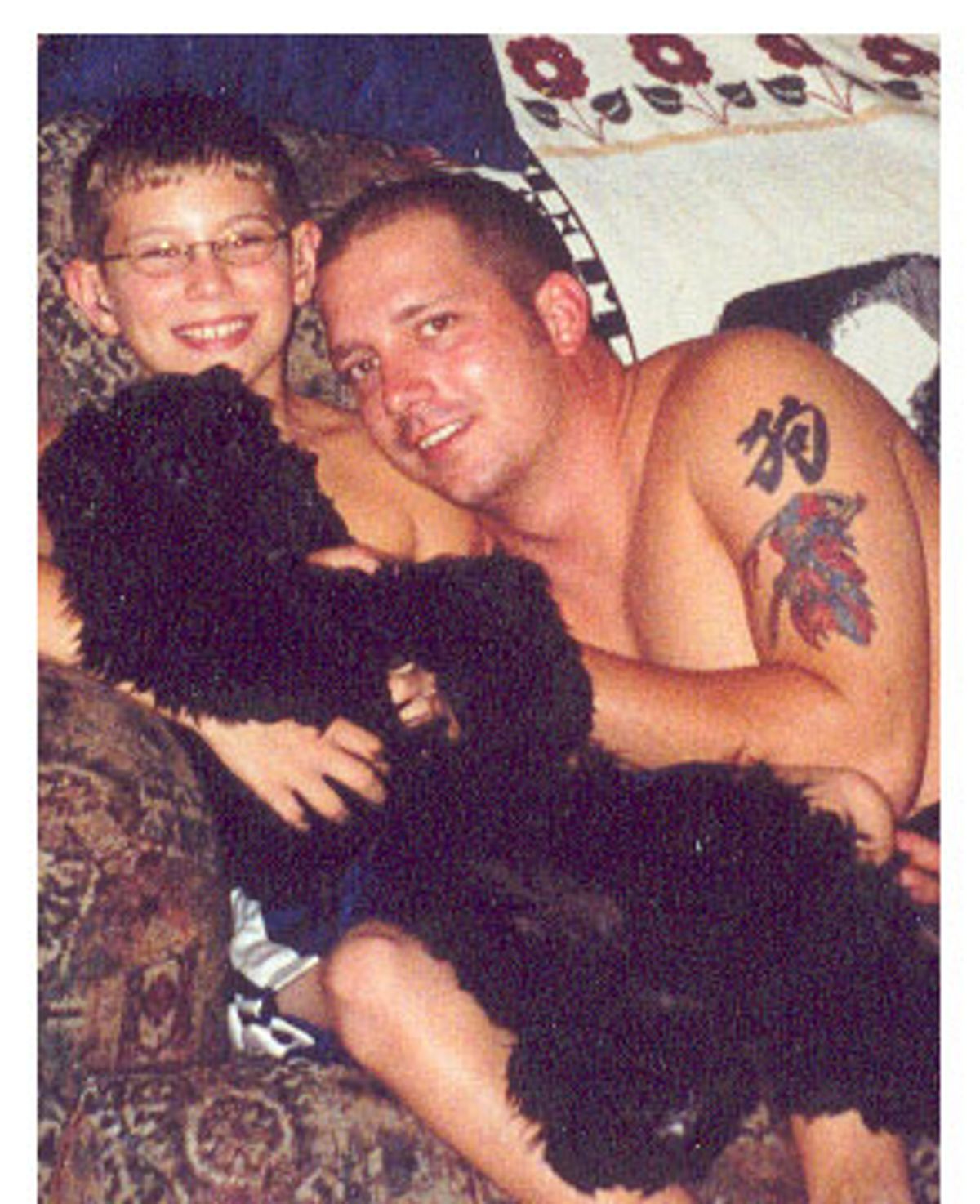

After graduating from high school in 1998, Micheal began feeling restless in Pulaski, but wasn't ready to go to college. He enlisted in the Army and was stationed in Fort Stewart, Ga., but still found time to come home and hang out with his 11-year-old half-brother, Jacob, who was born hearing-impaired. For hours, Micheal would lie on the living room floor with Jacob, patiently working with him on his homework. They rode bikes together and even went to the barbershop together, Micheal always instructing the barber to cut and shape their chestnut hair the same way -- "short on the sides, high in height," says Jacob.

In 2000, Micheal was in the midst of a peacekeeping tour in Bosnia when he received a letter from a biology student at La Roche College in Pittsburgh. Christine, then just 19, had been complaining to her parents that she never got mail at school. So on her mother's advice, she contacted an organization called Adopt a Platoon and was assigned a military pen pal: Micheal Dooley.

"There was nothing romantic about it at first," Christine remembers. "We were just two strangers writing each other." But after months of frequent letters and e-mails -- Christine wrote about her studies, Micheal about life in Bosnia and how much he liked the people there -- the two became close friends. When Micheal returned to the States in May 2001, he immediately drove to Pittsburgh for the day to finally meet Christine face to face. Although she wasn't expecting romantic fireworks, that's exactly what she got. "As soon as I walked into the hotel and saw him sitting there in the lobby, I instantly knew I would marry him," she says. "I started shaking and my heart was racing. He asked me what was wrong," she laughs. "But I definitely wasn't going to tell him."

Micheal's day trip turned into a weeklong stay. By July, he had chosen a princess-cut diamond engagement ring for Christine, and by the end of the year, she had moved out of her dorm room and into an apartment near Fort Stewart. The two married in a civil ceremony on March 7, 2002. "Just us," says Christine, "in T-shirts and jeans."

Soon after the wedding, with war in Iraq brewing, Micheal decided to reenlist in the Army for another four years. He and Christine were talking about starting a family and the promise of a steady job and salary -- even more than patriotic duty -- convinced him to stay in the military. But Micheal asked to be transferred to Colorado -- partly because he was ready for a change of scenery, partly because he wanted to try to avoid being sent overseas. (His old unit, the 3rd Infantry Division, was one of the most active, and was the first unit sent to Iraq.) "I know he believed this was his job and he would go if he had to," says Christine. "If he'd still been single, [being deployed] wouldn't have even fazed him. But we hated being separated. It broke our hearts."

In January 2003, Micheal and Christine bought a three-bedroom, two-bathroom house in Colorado Springs. Then in February, they returned to Christine's hometown in Plum, Pa., for a "real" wedding -- a huge church ceremony with all the trimmings, a DJ spinning Tim McGraw and Faith Hill at the reception. That same month, Christine also learned she was pregnant with their first child -- and that Micheal would be shipping out to the Middle East in April. "We didn't really talk about how we felt about the war," Christine says. "We didn't have political feelings about it. We were just scared on a personal level." Worried he wouldn't be home in time to see their baby being born in the fall, Micheal presented Christine with a going-away present before he shipped out: a small stuffed teddy bear dressed in scrubs to take with her when she went to the hospital.

As soon as Micheal left, Christine starting sending him care packages of Reese's Peanut Butter Cups, beef jerky, Newport cigarettes and cans of his favorite ravioli. They started writing letters to each other again -- Micheal liked Christine to spray every one with her perfume, Calvin Klein Escape --although the mail was incredibly slow and it sometimes took weeks to receive them. In his first letters, Micheal seemed optimistic about his mission, writing of how the Iraqis seemed happy to see the U.S troops. But as his unit drove deeper into the heart of Iraq, he wrote of the increased hostility toward Americans.

In a letter Micheal wrote to his mother on May 9 (which she received the day he died) he spoke mainly of dusty, hot hours of boredom, but gave no sense that he was in danger. "Just sitting around with nothing to do now that the war's over," he wrote. "I hope we don't stay here much longer ... I'm so excited about being a dad." "He never wrote me of being scared, mostly just how he wanted to come home as quickly as possible," says Christine.

Even before Micheal left for Iraq, his mother had a strong sense that her son would not be coming home. In February, she began having severe panic attacks. "I couldn't breathe, I felt my heart was pumping out of my chest," she says. "I couldn't eat, I couldn't sleep." She tried to hide her anxiety from Micheal, but he could hear it in her voice when they spoke on the phone. "Don't cry, Mom," he told her. "I'll be OK."

On the weekend her son was killed, Ann started to cry uncontrollably while at the furniture factory where she works, wrapping curio cabinets before they're boxed and shipped out. She had a nagging feeling in the pit of her stomach and says that instinctively she knew Micheal was in grave danger. "I knew my boy would come home in a box," she says. "I knew he would, but I never shared it with anyone." The unspeakable grief that gnaws at Ann every moment -- "I feel robbed by my son's death" -- is mixed with a bitter anger over the fact that she believes Micheal died for an unworthy cause.

"This war's political bullshit," Ann says, with fury in her voice. "It's all about oil and land. I think we should pack up the rest of the soldiers, bring 'em home, build a fence around the United States and fuck everybody who ain't American. Let 'em fight amongst their damn selves and let's take care of our own."

On Tuesday, June 17, during a thunderstorm, 100 people gathered for a memorial service in honor of Micheal at Holiday Park United Methodist Church in Plum, Pa., the same church where Micheal and Christine exchanged wedding vows just four months before. Micheal, who was promoted to staff sergeant two days before he died, was awarded the Bronze Star, Purple Heart and Army Commendation Medal after his death. The awards were presented to Christine by an Army colonel at the service. Although Micheal's mother and brother still live in Pulaski, Va., Christine chose to have Micheal's body laid to rest near her parents' home, where she's now living. "I want to be able to take the baby to see him," says Christine. "I know Micheal would want to be nearby."

Getting on without Micheal has been excruciating for his family members. Ann Davis is starting grief counseling this week. Jacob, who says he feels "numb" most of the time, spent the the spring trying not to fail out of school. After selling their home in Colorado Springs, Christine moved back in with her parents. She uses Micheal's shaving cream, she smells his deodorant. She takes the teddy bear with the surgical scrubs everywhere she goes, and it'll be at the hospital in October, when Shea Micheal Dooley is born.

"It's not like Micheal and I spent 50 or 60 years together and then he died of cancer," Christine says quietly. "We still had so much to do. We depended on each other for everything. And now he's gone ... Everything's like a funeral. I know it'll be the same with having the baby. Micheal's death is going to be fresh in my mind for a long time."

Shares