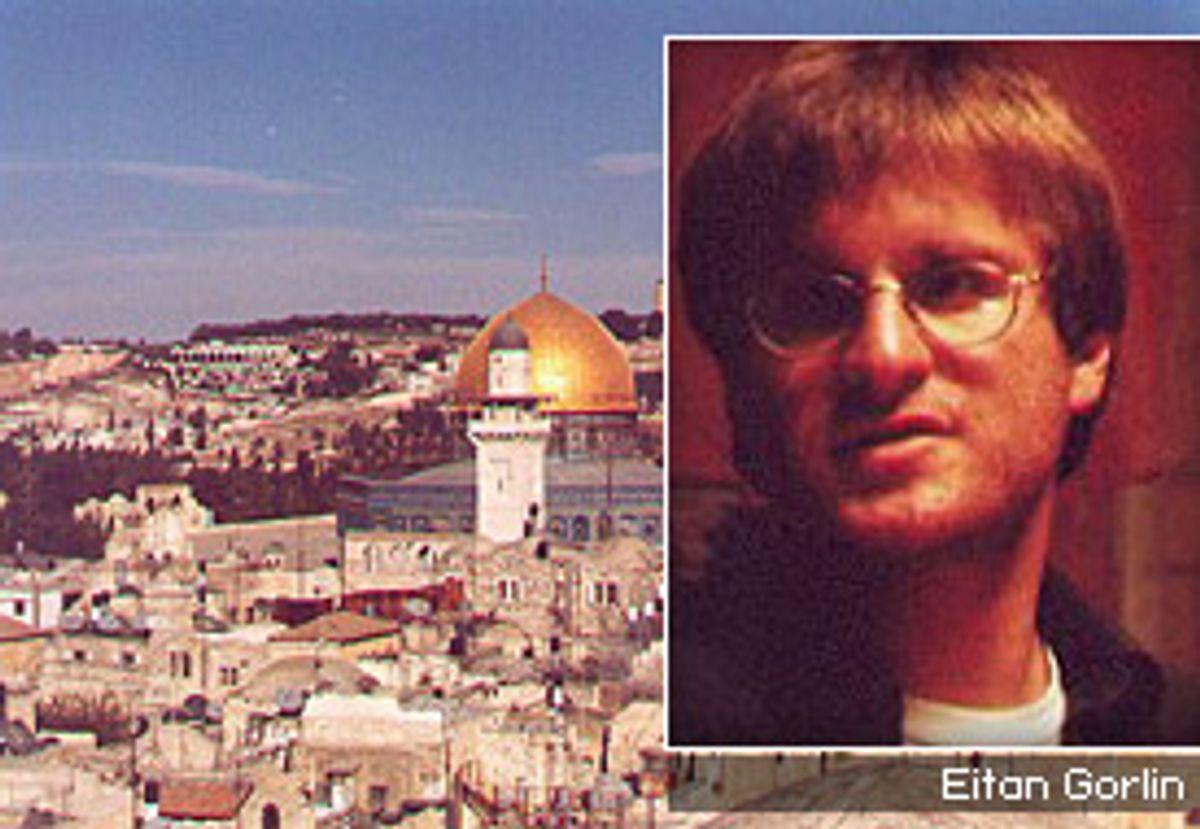

In Eitan Gorlin's first feature film, "The Holy Land," a befuddled young Israeli named Mendy (Oren Rehany), an Orthodox rabbinical student, spends his time masturbating and reading "Siddhartha" rather than dutifully studying the Talmud -- much to his rabbi's disappointment. But when the rabbi calls Mendy into his office to castigate him, he offers the sort of advice not usually associated with the clergy: Get it out of your system, get out of here, go to Tel Aviv. Go see a prostitute.

As the 34-year-old Gorlin explained, while this may seem like peculiar counsel from a man of God, the idea of relieving carnal desires is rooted in an obscure line from the Talmud. (Writer Nathan Englander also borrowed the line for his 1999 story collection, "For the Relief of Unbearable Urges.") The contemporary story in "The Holy Land" also has roots in the biblical parable of the prodigal son: Mendy, protected and beloved in an Orthodox religious community, seeks out danger and excitement in the secular world, only to find some of his most cherished dreams destroyed by the realities of post-Oslo Israel.

Will he return to his rabbi and beg for forgiveness, or will he continue to enjoy his new life as a bartender at the rowdy watering hole called Mike's Place? The real-life Jerusalem bar is where Gorlin worked during the first intifada and is the heart of the film. It's where Mendy meets "the Exterminator," a gun-wielding American-born settler; Razi, an Arab who collaborates with the Israeli occupation of the West Bank and, of course, Mike, the naive, loud-mouthed American war correspondent who came to Israel and never left.

At Mike's Mendy can also keep seeing Sasha, the sometimes angelic, sometimes angry Russian prostitute he met in Tel Aviv. As played by the lovely and beguiling Tchelet Semel, Sasha may only like Mendy for his innocence, for how different his life is from hers. But he's obsessed with her, either because he wants to save her or just because she's the first target of all his pent-up adolescent desire. Unfortunately, Sasha, Mike's Place and secular Israel itself come with ugly truths; Mendy must choose the complicated freedom of this world or the predictable safety of his parents' home.

Gorlin, an American-born Orthodox Jew who was educated at a Zionist yeshiva in Israel, spoke with Salon about the abuse of immigrants in Israel, the dark side of the roaring '90s and the Jewish community's reaction to his controversial film. "The Holy Land" is now playing in New York. It opens July 25 in Chicago, Aug. 1 in Los Angeles and in numerous other cities during the following weeks.

Considering all that's been going on in Israel in the past few years, I wondered exactly when the events in "The Holy Land" are supposed to take place.

It's supposed to take place at the turn of the millennium. But most of my experiences in Israel were in the first intifada, and in the early to mid-'90s. That was when I was a bartender at Mike's Place. For me, work at Mike's Place was a defining experience. "The Holy Land" is the third script I wrote. Before that, I set scripts in Nice [France] and in New York, and in both Mike and Mike's Place showed up. Mike was a Canadian war photographer. A lot of our customers were journalists and it had a gonzo atmosphere.

Was Mike's Place unique in Jerusalem? What made it special?

What was different was that it was more of an old-fashioned drinking bar. So it was diverse -- the clientele included the Irish construction workers who were doing work on the Dome of the Rock. They'd drink until 7 a.m. and then go in the morning to build. Some of these guys had been hostages of Saddam Hussein in the run-up to the first Gulf War. They were from Northern Ireland and everyone was always drunk, so between the accents and drunkenness I couldn't understand much.

We had these messianic types -- throwbacks to the late '60s, characters who never found their way back to America. They dressed like King David and played the harp. It's called the Jerusalem Syndrome -- they come to Israel and never leave. We even had people who were part of the counterculture and their most recent incarnation was as settlers. We had Arabs and journalists and street musicians. Mike's Place recently moved to Tel Aviv and was blown up in a terrorist attack a couple of months ago.

One of the most interesting characters was "the Exterminator," the American-born settler who hung out at the bar with his gun slung around his back, yet drank with Arabs at Mike's Place. Is he typical or exaggerated?

One thing about Israel is there are a lot of guns out in the open. The Israeli army is a civilian army and everyone between 18 and 21 is carrying a gun. The settlers always carry guns. The whole notion of "guns behind the bar" -- Mike would always say that. The Exterminator is a real story -- I was hitchhiking and someone who called himself "the Exterminator" picked us up and gave us a ride.

He gives Razi, an Arab character, a ride at one point in the film and defends him when he's being asked for his papers at a checkpoint.

Mike's Place is a bar -- there's a lot of bonding. Even though there's a political component to this film, the primary element is human. Razi is a collaborator -- one of those Arabs who have worked with Jews and worked with the occupation, that nebulous, in-between world. There was more of a subplot that explained the Razi character, but there was no room in the end to keep it in the film. You don't have to go all the way to Israel to find people like him. For example, there are racists who have one black friend and are very proud of that relationship.

Razi was selling himself as someone who helped settlers. When he meets the soldiers at the roadblock, he calls himself a real-estate broker: "Call me if you need help. I'm one of those guys who help you."

People will think you're trying to shatter myths with this film, to shake up common perceptions of Israel. Is that true?

I set out to tell the stories that I saw. I was not trying to shake up myths -- if that's the result, that wasn't my intention. My intention was to tell a story.

The main story centers on Sasha, a Russian prostitute, whom Mendy befriends and who is suffering in Israel. She is trying to make a living there, any way she can. When she talks about her life back in Russia, she refers to bread lines and poverty, yet her life in Israel obviously isn't making her happy either. Why did this story interest you?

You have a million immigrants who have come to Israel from the former Soviet Union. Most of the prostitutes have been brought there to be prostitutes. And in the post-Oslo situation where there was a lot of money, this phenomenon sprouted up. The prostitutes come specifically to work, but often they're smuggled in and their passports are stolen from them.

Are they smuggled in unwillingly?

I spoke to a lot of pimps. It varies. A lot of prostitutes are kidnapped and they have their passports taken from them. A pimp told me that what can happen is that the girls would be stolen from them by Palestinians and taken to the West Bank. There's definitely a lot of criminality going on with these girls. Some of the girls knew what they were getting into.

But the question is: Can you really say I'm going to work in another country, make money and come back? Or is it a line you cross and can never come back from? Some of them do make that calculation, that they can make more money in Israel and come back. But some are told they're going to be waitresses and don't come back.

This idea of crossing lines seems to be a major theme in the film. Mendy wants to get a glimpse of life outside of his closed-off Orthodox community and then doesn't want to return. But were you also making a comment about the Orthodox community in Israel, that they're so separated from secular life in Israel, that it's almost like they live in a separate society?

We chose the title "The Holy Land" and there's a certain biblical component -- the prodigal son story. The story of the prince who was raised in a palace who can see life on the other side of the wall and begs his father to leave. At first it's very exciting and then he gets beat up and knocks on the castle door and says, "Dad, can I come home?" There is a level of parable, and there are more universal themes -- the idea is to make them both work. But certainly some of the things Mendy represents in his journey don't just represent Orthodox Jews in Israel.

One of the most surprising moments in the movie is when Mendy's rabbi suggests that he go off and see a prostitute to get some of his sexual urges out of his system so he can come back and concentrate on his studies. Does that really happen?

It's rare for a rabbi to do that. But that quote that I reference [that the rabbi uses to justify his order] does exist in the Talmud. There is a very important theme in Orthodox Judaism, a philosophy that you need to build fences around laws, you need to keep protecting and protecting. But Mendy's rabbi was taking a risk. You have rebels within the Orthodox world -- they look the same, but there's something revolutionary in their thinking. This rabbi was something of a maverick. That's why he's so disappointed in the end, because he believes in Mendy. This rabbi, in his own way, is taking a risk.

Did political events in Israel affect either the story line of the film or your ability to produce it? I ask because it seems that political views can alter radically over there, depending on when the last suicide bombing occurred.

What's interesting is that most of my writing was about my experience in the first intifada. When we came to make the film, it was one of these windows of peace, at the end of 1999, when we thought the Sinai would be the Middle Eastern Riviera and all that. So that allowed me to focus on things like the exploitation of foreigners, because the Israeli-Palestinian conflict had receded into the background. I could focus on sociological and psychological issues.

There was so much money. It was the dot-com, Bill Clinton era; the dark side was the exploitation of poor people. Israel has probably half a million foreign laborers -- you'd be overwhelmed by how many Thai and African and Polish people are there. In a sense the movie was able to speak to what was going on in the '90s around the world.

Apparently the film has been rejected by three American Jewish film festivals. Why do you think that happened? Do Jews have problems with the film?

Especially American Jews. There's a real desire among a lot of people to control images and messages and the story of Israel. People are used to propaganda: "You're either with us or against us." I like to think the film has ambiguity. Some Jewish film festivals are more a celebration of our culture. They just don't want to go there.

Shares