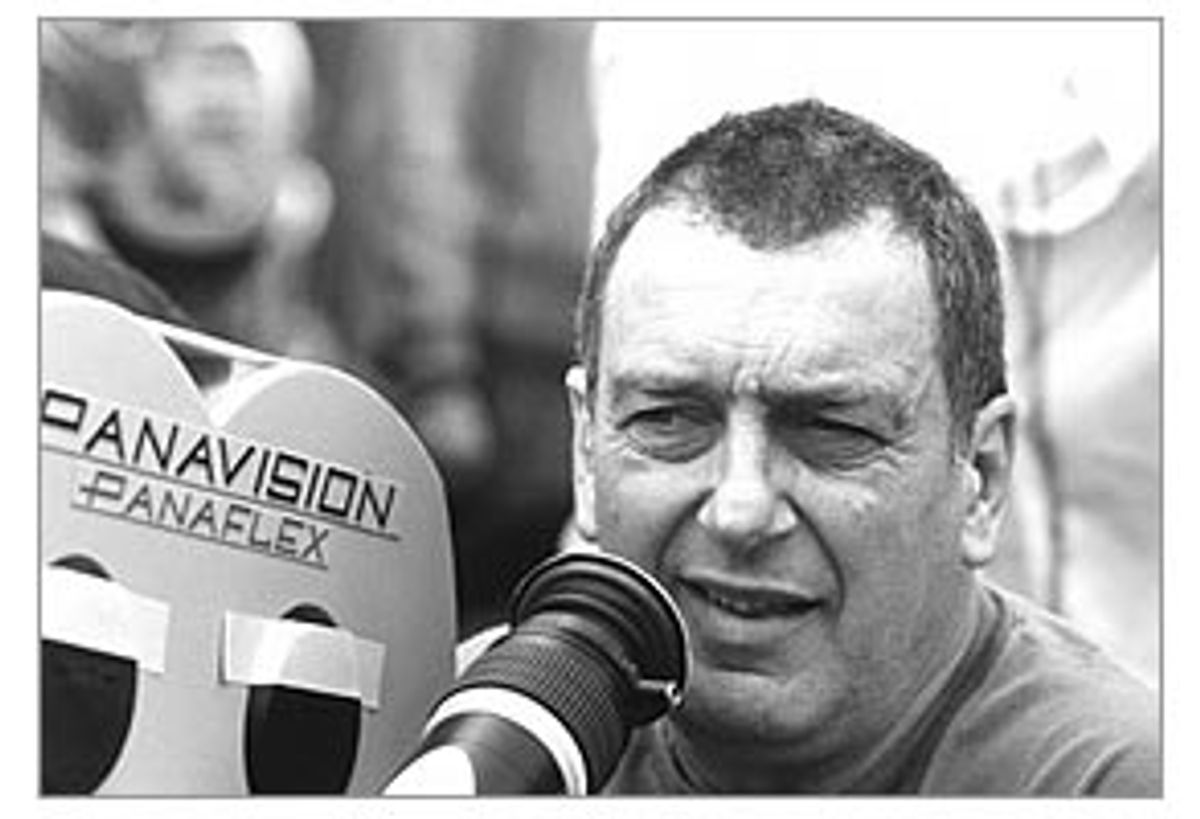

Stephen Frears is on a roll. His new movie, "Dirty Pretty Things," a romantic thriller about illegal immigrants in London, opened last week to strong reviews in New York and Los Angeles, six months after opening in Britain and receiving wide acclaim there as the movie of the year. Now the director has just finished shooting "The Deal," a television movie about the complicated relationship between Prime Minister Tony Blair and the man widely perceived to be Britain's second most powerful, Chancellor of the Exchequer Gordon Brown (roughly equivalent to the Secretary of the Treasury in the American cabinet). The two films -- one about the machinations of powerful men, the other about how their decisions affect the most powerless members of society -- could almost be taught back-to-back as a seminar on modern Britain.

Certainly, "Dirty Pretty Things" could hardly be more timely. A month before the film opened in London, the British government announced a sweeping new immigration policy that included closing the Red Cross-operated Sangatte refugee center near Calais in France. Sangatte's position near the Channel Tunnel had made it a notorious magnet for refugees trying to get across to Britain, and for the human traffickers who helped them. But its closure -- along with other reforms designed to deter refugees -- has ignited fierce debate about immigration policy in Britain.

Frears' film tells the story of Okwe (Chiwetel Ejiofor), an illegal Nigerian immigrant who works by day as a minicab driver and by night as a desk clerk at a posh London hotel. After befriending one of the hotel's chambermaids, a Turkish asylum seeker named Senay (Audrey Tautou of "Amélie"), Okwe discovers that the hotel manager (Sergi López) is conducting some secret and distinctly unsavory activities in the hotel, preying on the desperation of illegal immigrants.

From there, Frears' film pitches audiences into a grim underworld of London's hidden sweatshops, minicab offices and mortuaries, as Okwe and Senay struggle against a system bent on crushing them. The film is an unholy mixture of genres -- thriller, social drama and love story -- but somehow Frears pulls it off. A taut script by newcomer Steve Knight (who, bizarrely, is one of the creators of the television quiz show "Who Wants to Be a Millionaire") helps make "Dirty Pretty Things" as entertaining as it is eye-opening, and there are fine performances by a truly international ensemble cast -- especially from Ejiofor, a British theater actor who, on the basis of this performance, will be able to write his own ticket in Hollywood.

It's worth noting that "Dirty Pretty Things" takes viewers beyond such recent lily-white depictions of Britain as 2001's "Bridget Jones's Diary" and 1999's "Notting Hill" (which was set in a London neighborhood that is, in real life, predominantly black). For Frears, who jokes about "Dirty Pretty Things" that he "went to great lengths to ethnically cleanse my movie of white characters," the movie is a return to some of the themes he explored in his 1985 breakout hit about immigrants in London, "My Beautiful Laundrette."

In between the two films, Frears has assembled arguably the most diverse portfolio of any director working today. He's never met a genre he didn't like, or so it would seem from his dips into romantic comedy ("High Fidelity"), period drama ("Dangerous Liaisons"), contemporary noir ("The Grifters") and the western ("The Hi-Lo Country"). He has portrayed gay relationships memorably in "My Beautiful Laundrette" and "Prick Up Your Ears," and has adapted for the screen two of Roddy Doyle's Barrytown trilogy novels, "The Snapper" and "The Van." While not everything he touches turns to gold ("Mary Reilly" was a low point for both him and star Julia Roberts), Frears has an impressive track record. Unlike some of his fellow British directors, he has stayed close to his roots, and for every Hollywood project he takes on, there's a riskier, low-budget British movie he seems to undertake out of love, like "Liam," his 2000 film about Liverpool during the Depression.

Given the political climate in Britain at the moment, "The Deal" might be his riskiest project to date. In April, Britain's ITV television channel dropped the film, fearing it wouldn't get government approval for a merger if it depicted Tony Blair unflatteringly (the channel also expressed concern that Blair might be forced out of office by the time the film screened in September). The movie's title is based on an infamous 1994 dinner at which Blair and Brown, both rising stars in the Labour Party, purportedly struck a deal that allowed Blair to assume the leadership of the party and become the next prime minister. (What Blair might have offered Brown in return isn't known). As the hunt for Iraq's weapons of mass destruction continues and Britons increasingly wonder if they can trust Blair, "The Deal" could provide a valuable window onto the troubled P.M.'s soul.

Salon recently reached Frears by telephone at his country home outside London.

"Dirty Pretty Things" is an unusual movie in that it's a blend of social-political drama and exciting thriller. What was your reaction when you first read it?

That was the quality I liked about it, that mix of things. Also it was clearly very modern and described modern Britain in a way that hadn't really been seen before.

Did you want the movie to have an impact on the public debate that's going on in Britain right now about immigration and asylum seekers?

Actually, I don't think this is a very political film. Really the only thing it's arguing for is a bit more kindness toward people. It goes without saying that if you treat people brutally, they'll treat each other badly and a criminal hierarchy will spring up whereby the poorest people get exploited.

Perhaps the film isn't overtly political, but you do take the audience on a visceral tour of this underclass in London, and the effect is eye-opening. Would you be happy if audiences were politicized by the movie?

Well, on the whole I guess it's better that you know there is this underclass in England, and that it's treated like this.

But if, say, people were inspired to go out and campaign for Amnesty International...

Of course. How could anyone object to that?

How would you explain what's happening in Britain at the moment around the issue of immigration and asylum seekers?

I can see that people are very frightened of changes in society. I have a house in the English countryside, where I'm sitting now, and I'd be surprised if there was a black man within 10 miles. It's like the 1940s down here, it's so old-fashioned. In London, though, I live in a multicultural part of the city, and it seems obvious to me that we've benefited from immigration. Certainly the British economy has benefited, and I'd argue that the changes in society are valuable. But people get frightened -- of losing their jobs, or of some terrible smell coming from the house next door. That's just fear of the unknown. America's an entirely immigrant society and it doesn't seem to have done so badly.

It's bizarre that the person who wrote this movie, Steve Knight, also created the quiz show "Who Wants to Be a Millionaire?"

Yes, it's incredible, isn't it?

Do you know how he got from there to here?

Well, he made a lot of money from the show, and it turned out that what he really wanted to do was to write feature movies. One of the main characters in "Dirty Pretty Things," the Turkish girl [played by Tautou], was based on a friend of his. I know that he's a very observant and curious fellow, and very open. All the story's freshness and originality came through him.

You made some interesting casting choices for this movie. Had you seen Audrey Tautou in "Am&eaute;lie"? If so, did you wonder if she'd be able to go from that character to a downtrodden Turkish asylum seeker?

Not really, because when I saw the movie, I was just open-mouthed in admiration of her talent. Audrey did come up to me at the premiere [of "Amélie"] and say, "I don't want you to see this movie." And I said, "Well, I'm going to." She was saying, Don't imagine this is all I can do.

Chiwetel Ejiofor is pretty much unknown in the U.S., but his performance here really anchors the movie. Did you have any idea how good he'd be?

No. He was clearly a good actor. But the gap between that and taking the whole thing on your shoulders is huge. You ask an awful lot of people and you obviously try to help them and give them confidence -- but he was fantastic.

You just finished shooting "The Deal" for British television, about the relationship between Tony Blair and Gordon Brown.

[Laughs.] Yes -- a portrait of a marriage. Another of my gay films!

What inspired you to take it on?

I was sent the script, and again, it just seemed rather interesting. Indeed, it has been very interesting to deal with the most recent part of British history, the stuff that's in every newspaper in the country.

Does the film answer the big question about what Blair promised Brown in return for the leadership of the party?

No, because I wasn't there. Only two people know the answer to that question.

But the film is a work of fiction...

It's fictional because I wasn't there, so by definition it's fiction.

So you could offer an answer.

I imagine the answer has to do with the fact that Blair is a lawyer, so he's capable of saying things in a way that other people can interpret how they want. It's all to do with the gaps between words. Clearly he said something Brown wanted to hear and could interpret in a certain way.

What's your personal opinion of Blair's behavior over the last few months?

It's been a rather melancholy story over these last few months. I don't think anyone in the country trusts him, basically. He's clearly an extremely clever, capable man, and the tack he's taking is rather mysterious. It's like watching someone almost incapable of speaking the truth.

That's interesting, because on this side of the Atlantic he's perceived as the great statesman, a kind of unofficial secretary of state for the Bush administration. And he does have vision -- he gave that fantastic speech to the Labour Party conference in Brighton just after Sept. 11, where he talked about African development and the Middle East peace process.

That was a wonderful speech.

So what happened between then and now?

[Laughs.] Well, we invaded Iraq, for one. I don't know. I could see that what happened to the Twin Towers was so dramatic that it could explain anything, and obviously, anyone would hold out the hand of sympathy. But this evasiveness is quite noticeable. I think Blair thinks he's been acting as a restraining force on Bush -- but I'm not sure that we in Britain think he has.

Do you think that the whole issue of the missing WMD will bring Blair down?

I don't know that it will bring him down. I certainly think it's made people very wary about trusting him.

Did making the film give you any insight into his motivation?

Not really. He's very hard to read.

You're known for getting great performances from actors, and you've launched a few careers -- Daniel Day-Lewis' breakout movie was "My Beautiful Laundrette," and Uma Thurman's was "Dangerous Liaisons." What have you learned over the years about how to get the best out of people?

It's like bringing up children, isn't it? If you love them, they'll blossom. Firstly, I'm overwhelmed by my admiration for actors. I think their talent is phenomenal, and their wit and inventiveness. So I try to create conditions in which they can work, and I encourage them to be inventive and muck about. I love what they do. But I can see that a lot of people find them frightening.

"My Beautiful Laundrette" was the film that opened the doors for you to work in Hollywood, and since then you've flipped back and forth from blockbusters to low-budget projects. Apart from all the money, is there anything working in Hollywood gives you that independent movies don't?

Oh, yes. It's terrifically interesting. It's full of very clever people that set new problems that have to be solved. I can see the work I've done in America playing into "Dirty Pretty Things" -- the whole business of entertaining people and getting them into cinemas. The film deals with that in a way that I haven't always dealt with in the past. I started my career making films for television, where there was a captive audience, so we never had to think about getting people hooked. But American films are, after all, what most people watch most of the time, so it makes sense to look at what they're doing well.

You say that, but it seems to me that not very many films coming out of Hollywood these days have the qualities that make "Dirty Pretty Things" stand out: It has a satisfying narrative arc, compelling characters, and a script that doesn't talk down to the audience.

Well, I suppose I don't like the films as much as I used to. But there are incredibly intelligent people working there.

If that's the case, why are we getting so many sloppy movies?

It helps not spending a huge amount of money. If you don't spend very much, people are more likely to leave you alone and let you get on with it. Once you spend more, they obviously get nervous and try to hedge their bets.

You have one of the most eclectic bodies of work of any director.

I'd say so.

What do you look for in a script?

I don't think about it. I just read something and think, "Great." I'm completely indiscriminate -- I just make the ones I love. Afterwards I sometimes look at the film and think, "Ah yes, that was why I wanted to make it."

You've passed on a few big movies. You had an opportunity to direct "Thelma and Louise," for example.

I never actually read it. I was offered it, but I was up to my eyes making "The Grifters." But it was careless of me. I got a message that the script wasn't as good as all that. Then, when I saw the film, I thought that the message hadn't been a very good one. But I thought Ridley Scott made it really well, though; I don't think I would have made it as well as he did.

Are there any genres you haven't worked in yet that you'd like to try?

I don't really think in terms of genres. I just read scripts and react to them.

So it's possible in the future that we could see a Jerry Bruckheimer-Stephen Frears movie?

Well, it sounds unlikely. But, you know, he did ask me to do a film a couple of years ago.

Really? An action movie?

Yes, absolutely. I mean, I like them as much as anyone else. Whether I'd be any good at directing one or not, I wouldn't know.

There's only one way to find out.

[Laughs]. Yes. Or you could go to the grave without knowing.

Shares