What if you didn’t have a party and everybody came? That’s the premise behind the Mob Project: To create inexplicable mobs that gather in New York for 10 minutes or less.

On July 2 at about 6:30 p.m., feeling way shady and surreptitious, I ducked into the Grand Central Station food court and scanned the scene. Mobsters had been instructed, via e-mail, to locate a person carrying the New York Review of Books to receive further instructions. As I’d arrived a bit ahead of the appointed 6:45 meeting time, I claimed a seat and perused my New York Times, only to be interrupted by at least six other early birds who sidled up to me and asked, out of the corner of their mouths, if I was with the mob. At the appointed time I stood, folded my paper and began searching — joining the hordes of shifty-looking lurkers also discreetly trying to locate the New York Review of Books person (and, incidentally, avoid the armed National Guardsmen). I finally found him by simply following the stream of people leading to a guy hunched in a corner, passing out strips of paper printed with directions. At 7:02, we gathered in the lobby of the Grand Hyatt; at 7:07 about 200 people ascended the stairs to the mezzanine. At 7:12 — the moment of truth — we applauded for 15 seconds. And then the mob dispersed as quickly and quietly as it arrived.

So what exactly is the point?

“It’s a way to show your inner freak show,” said Alex, 32, who’d read about the event on the listserv NonsenseNYC.

“It’s random art,” said his companion, Zeke, an investment banker.

So it’s performance art?

“Well, only in that the definition of performance art has been so expanded,” says organizer Bill, 28, who declines to give his last name and will only say that he works in the “culture industry.” “It’s a purely social event. The point is unique to each person.”

Indeed, as I ask around, the points are many and varied, though a few themes do recur. At a separate downtown gathering two weeks later on July 16, Susan, 21, who heard about the project from a friend, said, “It’s sort of like being at a protest, but without the politics.” Melanie, 22, agreed, “It’s not like you have to have a cause, to be an activist.”

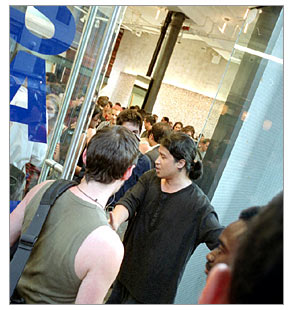

By 7 o’clock that night Susan and Melanie and about 300 others, median age about 25, had gathered at one of four bars in downtown Manhattan, ready to kick off the fourth and latest mob. The right bar for you was determined by birth month; being a December baby, I took a seat at the bar of Pamela’s Cantina on West Third Street and waited for the mob representative. At 7:05 a furtive-looking guy, hidden under a dark hat, began handing out slips of paper indiscriminately — apparently assuming that the entire clientele of Pamela’s was part of the project. And it seems he was right, as at 7:07 nearly every patron picked up and began skulking en masse down Lafayette Street, trying not to arrive at Otto Tootsi Plohound, a trendy SoHo shoe store and the venue for the night’s mob, before the magic moment of 7:18. As we walked up to the store, a mob of people was already pouring in, seriously startling the staff.

About 200 people squeezed into the store, a medium-size boutique that specializes in outfitting the dainty feet of downtown’s trendiest ladies, before a salesman bravely flung himself against the tide to wrestle the door shut and lock out about 100 more, who had to content themselves with pressing their noses against the glass. Flashbulbs flashed, microphones waved — the approximately 100-person difference between the third and fourth mobs seemed to be entirely made up of media. Approaching the store from the north, I saw hundreds of people surging forward, photographers standing on stools and lampposts trying to get a shot, radio journalists muttering into their recorders.

“Is someone famous in there?” asked a tourist who stood on the sidewalk.

“Nooo,” replied several of the mobsters, clearly unsure how to answer. The slip of paper had instructed us to identify ourselves as “tourists from Maryland shopping for shoes,” but no one could bring himself to say it with a straight face. Apparently, following secret instructions and storming a shoe store is all in a day’s work, but lying to a harmless tourist, well, that’s just mean.

Finally, the project was explained — truthfully — and the woman nodded her head understandingly. So, what did she think about it? “It’s New York!” she said brightly. “And that’s why I live in Florida!”

But it’s not just New York. So-called flash mobs or smart mobs apparently appeal to hipsters nationwide, from San Francisco to Minneapolis to Duchess County, New York. (Mobs are also being planned in Boston, Vancouver, London, Rome and Phoenix, Ariz.) Although anyone who can surf the Web can find the instructions, the mobs were originally supposed to be invitation-only, distributed by a viral e-mail campaign. This mob snobbery seems to be at least a small part of the appeal; several mobsters in the New York said they felt good about being on the inside of a joke.

“You’re freaking out the squares,” said Ryan, Melanie’s boyfriend, a 20-something with a broad face and dark hair. Bill, the organizer, who actually is from Maryland, disagrees: “If you’re walking down the street and you see all these people, and you’re like, what the heck is that, you’re suddenly on the inside of the joke also — you don’t know any less than these people do. There isn’t an elitist impulse, it’s intended to be a mob — to be as large as possible.”

Pressed again to explain the point of the Mob Project, Bill stumbled a little: “There are different aspects, for which different people like it. For me, the point is to transform the space around us — and I don’t mean in the pretentious way that it sounds. In New York we encounter crowds every day, but they’re crowds in which we’re kind of in competition with everybody else there — like we’re all trying to get on the same subway train. Our attitude is, ‘I wish these other people weren’t there.’ And, to me, the idea of the mob is to create a crowd that wasn’t there before, for no reason, to change the flow of where people are in the city. And suddenly to have people appear in a place and then dissipate — it’s a cooperative thing.” He pauses. “It really is for no reason.”

Jonathon, a tall, slim 30-year-old with shaggy hair, enjoyed a cigarette as he ambled down Lafayette Street; he was initially reluctant to talk, as he was recently quoted for a Friendster article and feared coming off as a “hipster doofus.” However, he did say, “It’s scenesterism taken to an absurd level.” His companion, Jake, also 30, countered, “That’s a little cynical. It’s zeitgeist stripped bare … It’s urban festivity.”

While we were smushed outside Otto Tootsi Plohound, discussing the meaning of the mob, a middle-aged gentleman came up and peered in the window: “Wow, they must have really great shoes here.”