Philip Gold, a former Georgetown University professor who worked on Steve Forbes' presidential run, says that when he talks to conservatives about the direction of America under President George W. Bush, he senses a clammy, middle-of-the-night kind of fear. "I am getting more and more a sense across the board of enormous apprehension," he says. "There's this whole 3 a.m. sense of, 'What are we doing?'

"Between this recession that ended statistically but not in real life, and all the little lies or fabrications and falsehoods in Iraq and elsewhere that are starting to add up to one big problem, there's so much diffuse anxiety right now," he says.

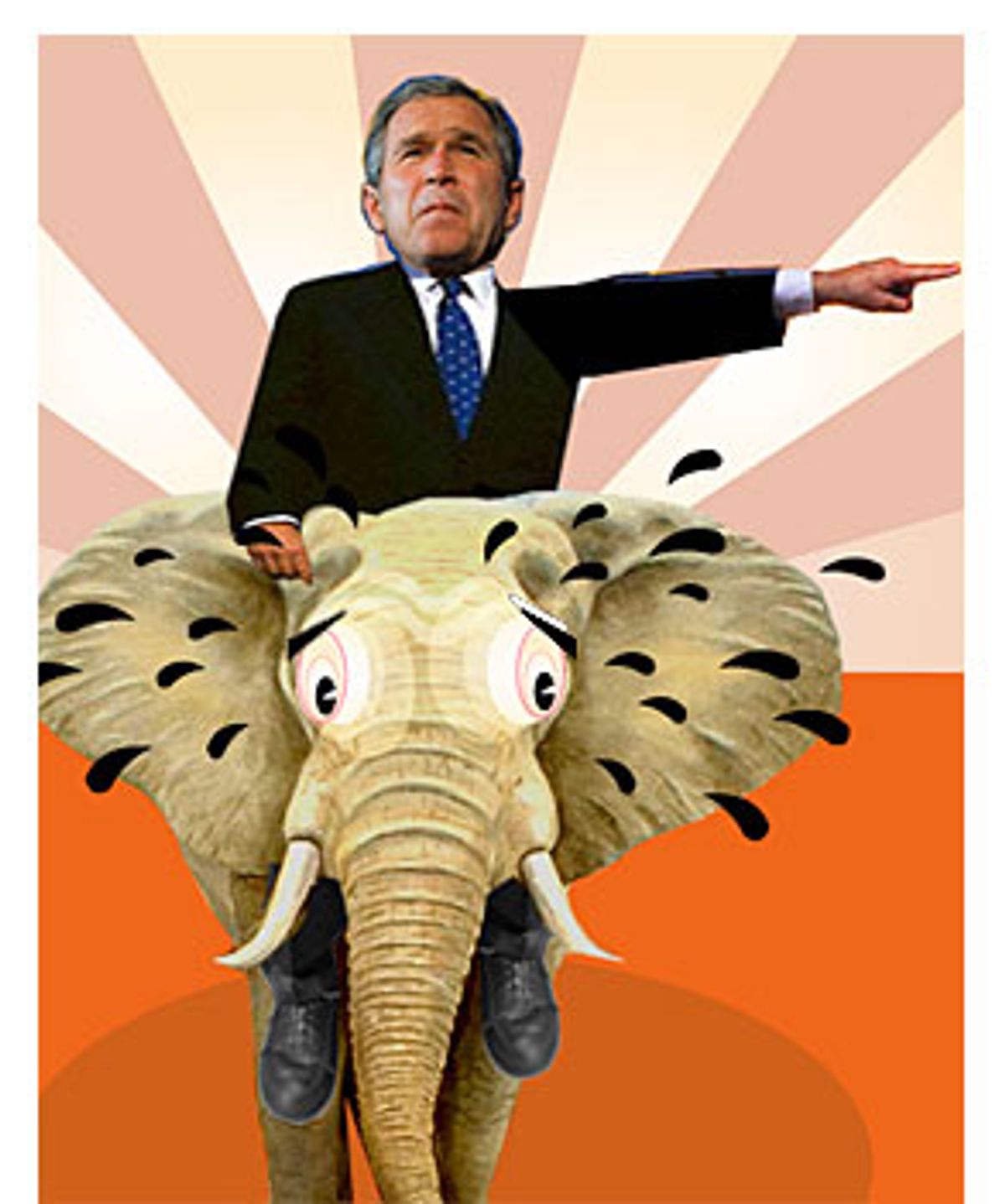

Bush is still beloved by the Republican rank and file, the people who participate in voter drives and turn out on Election Day. Increasingly, though, there's unease among some of the party's elders, including veterans of the Reagan and Bush I administration. It's not principally about Bush's poll numbers, though they're going down, or about the 2004 election, though it's shaping up to be more competitive than most predicted a few months ago. It's about something more fundamental. Though they don't like to say it, when they look at the economy and Iraq, they can't help worrying about where Bush is taking the country.

Bush, with his tax-cutting fervor, Manichean foreign policy rhetoric and disdain for church-state separation, appears to liberals as the apotheosis of Republican conservatism. Yet plenty of Republicans don't recognize their ideology in Bush's lavish deficit spending and the grandiose, world-transforming neoconservative foreign policy he's adopted.

Last week, the Wall Street Journal ran a story about a new group called the Committee for the Republic, formed to spark a discussion in the establishment about America's lurch toward empire. Its sponsors include Republican Party loyalist C. Boyden Gray, a lawyer in the first Bush administration. The Journal quoted a manifesto the group is circulating, saying, "Domestic liberty is the first casualty of adventurist foreign policy ... To justify the high cost of maintaining rule over foreign territories and peoples, leaders are left with no choice but to deceive the people."

Republicans, after all, are traditionally averse both to nation building and to the whole idea of humanitarian intervention. Until now, the rise of neoconservatism, a movement dominated by ex-liberals who dream of remaking the world through American military might, has eclipsed such old-school realism (or isolationism), but with American soldiers dying almost every day and the Iraq war costing $1 billion a week, some Republicans are challenging their party's direction. As George Will wrote in a July 24 Washington Post column titled "A Questionable Kind of Conservatism": "The administration ... intimates that ending a tyranny was a sufficient justification for war. Foreign policy conservatism has become colored by triumphalism and crusading zeal. That may be one reason why consideration is being given to a quite optional intervention -- regime change, actually -- in Liberia."

"The neoconservative foreign policy is not the traditional foreign policy of the Republican establishment," says Lawrence Korb, director of security studies at the Council on Foreign Relations and assistant secretary of defense in the Reagan administration. "Bush's father was kind of the last of the Republican multilateralists." Under Bush I, he says, "We went in, threw Saddam out of Kuwait, then we went home. The neocons said, 'No, you should go after and get rid of Saddam.' Bush 41 was saying, 'Do we want to get tied down there forever?'"

Establishment Republicans, says Korb, are "very alarmed. What they see, basically, is us spending more than we have and not putting the money away to deal with the coming burst of baby boomers who will be retiring."

It's not just so-called moderate Eisenhower Republicans like Korb who worry about Bush. Some conservatives are also fearful. In addition to the Iraq war and the economy, they were already troubled by the USA PATRIOT Act's erosion of privacy rights, and they're angry at Bush's new Medicare prescription drug entitlement, which they see as an intolerable expansion of the federal government.

"At the grass-roots level there is not a great deal of anxiety yet, but a lot of conservative leaders are quite apprehensive," says Don Devine, vice chairman of the American Conservative Union and former director of the Office of Personnel Management in the Reagan administration. "All of this disturbance [in Iraq] was predictable and predicted. As long as the administration doesn't believe its own rhetoric on trying to create a Western democracy there and gets out before they get too involved in nation building, it probably can be handled. If the strategy is to stay there until we turn it into a Western democracy, it would be a disaster."

Devine emphasizes that he's speaking for himself, not the American Conservative Union, the country's oldest conservative lobbying group. But he says he's far from alone as a conservative leader who's lost faith in Bush's fiscal and foreign policies. "Many of them were very concerned about getting into Iraq in the first place," Devine says. "Once it was clear that Bush was going to do it, the conservatives didn't want to do anything that could jeopardize a military operation, but there was concern the whole time, though it was pretty much muted."

As for the economy, he says, "Anyone with an economic conservative view of the world has to be quite concerned" about Bush's spending. "Sure, tax cuts are a good thing, but they're not everything.

"I think you're going to see more criticism as time goes by," Devine continues. "The Medicare drug bill, the largest expansion of entitlements since the Great Society, is very much under criticism. I think it has kind of woken up conservatives to the need to do something about restraining government spending."

Still, don't expect an intra-party battle anytime soon. Even those Republicans who are deeply worried about the Bush presidency have little incentive to speak out. "For those who make their livings based on politics and what happens here in Washington, who else are you going to support if you consider yourself either a conservative or a Republican?" asks Charles Peña, director of defense policy studies at the libertarian Cato Institute. "If you go against [Bush], that's, if not treasonous in a political sense, almost implying you'd prefer to have Bill Clinton back in office or Al Gore running the show."

Conservative leaders know criticizing Bush jeopardizes their role in the movement. "You have to make a big distinction between the grass roots and the leadership," says Devine. "The grass roots love him, and that's another reason why conservatives aren't very vociferous, because they know their troops aren't with them."

Besides, says Gold, the right dreads sounding like the left. He points to the Vietnam era, saying, "By 1966 and 1967, supporting the war was a way of opposing the people who opposed the war. We're seeing something very similar here with a kind of quiet, 'give him the benefit of the doubt' attitude, coupled with a real aversion to sounding like the left." Republicans, says Gold, think, "We're against the people who are against Bush."

Even so, the doubts about Bush that are bubbling up among Republicans show that the aura of omnipotence that surrounded the president just a few months ago is dissipating. Radiant with victory right after the fall of Baghdad, Bush and the neoconservatives who dominate his administration had seemed invincible. Yet as the death toll in Iraq and the deficit in America both shoot upward, neoconservativism has been discredited in the eyes of many. And Bush, says Peña, is now irrevocably tied to neoconservatism. "There's no going back for him," he says.

Before the war, Republicans who doubted Bush's course were aggressively marginalized. "The Bush administration was so sure of itself, so sure that it could handle Iraq, that it was unwilling to listen to those who disagreed with its policy on Iraq," says John Mearsheimer, an acclaimed foreign policy realist at the University of Chicago. "It dismissed them out of hand as appeasers or fools." Sen. Chuck Hagel, R-Neb., and Bush I veterans James Baker and Brent Scowcroft all warned against Bush's course, and all were "tarred and feathered by the neocons," he says.

Other Republicans were simply caught up in the administration's confidence. "Before the Iraq war, the feeling was that the United States would go in, get rid of Saddam, lop off a few of the top Baathists, and you would still have a functioning [Iraqi] military and police force," says Korb. "We could get in and out quickly.

"It was 'The Best and the Brightest' No. 2," he says, referring to David Halberstam's classic about the intellectual elite who were the architects of the Vietnam War. "All these people with tremendous accomplishment, they let their beliefs in American power and American values carry them away."

Indeed, says Mearsheimer, Iraq was always about much more than Saddam Hussein and his alleged weapons. "Their scheme involved not only Iraq," he says. "They were talking about democratizing the entire Middle East. Iraq was just the first step, and it was going to have a democratizing domino effect. We were going to transform the Middle East at the end of a rifle barrel. The result would be the disappearance of terrorism and we'd solve the nuclear proliferation problem."

Instead, says Mearsheimer, Iran has redoubled its nuclear efforts, while North Korea has been unbowed. As Korb points out, former Clinton Defense Secretary William Perry gave an interview to the Washington Post last week warning, "I think we are losing control ... It was manageable six months ago if we did the right things. But we haven't done the right things ... I have held off public criticism to this point because I had hoped that the administration was going to act on this problem, and that public criticism might be counterproductive. But time is running out, and each month the problem gets more dangerous."

Such a threat, coupled with instability in Iraq, "will sober up people who believe in American omnipotence," Korb says.

"What the Iraq thing has shown is the cost of empire," he says. "Who's going to pay for it? Are you going to need a bigger military? Are the American people going to get tired of running this empire and then not fund what they really need to for national security? That's what happened in Vietnam. We extended ourselves trying to fight Soviet Communist expansionism, and we went into an area where it was really hard to make that connection. We got 579,000 people tied up there, and it turned the American people against defense, so that in the '70s they wouldn't even spend what was necessary."

He sees the current situation imperiling American security at home. "What do we spend on homeland security, roughly $40 billion, and the police and firemen are saying they don't have enough -- the police in New York don't even have [adequate] communication equipment or protective clothing," he says. "How much are you spending on Iraq a year? Fifty billion. And at the same time you have these escalating budget deficits."

None of this means the party is going to rupture or turn on its leader. "The president is hugely popular within the party for tax cuts," says Peña. "He is in fact a bigger spender than Clinton was, but conservatives love his rhetoric and they seem to be much more forgiving of the implementation of it. Besides, if you're a well-to-do businessman and you get your tax cuts, you look at your own wallet, and if you are affected positively by this presidency, you may not be 100 percent happy, but you're going to keep your complaining to a relative minimum."

Still, there are already small signs that Bush's power is weakening. On Wednesday, the House voted overwhelmingly to block a new FCC rule that would allow a single company to own television stations reaching 45 percent of American homes, up from the 35 percent cap that exists now, despite Bush's threat of a veto. The new FCC rule was backed by big media companies, but opposed by a coalition of liberal, religious and conservative political groups.

Meanwhile, Peña suggests that some Republican critics of Bush's foreign policy want to distance themselves from a political faction that might be compromised. "For people who make their livings in the world of politics, who you get associated with matters," he says. "If there are people who feel this is going to end up being an albatross around Bush's neck, and it very well could be, they aren't going to want to be tainted by that because they have aspirations beyond this administration.

"If we look back a year from now, or six months from now, this July may be a watershed month for this administration and the neocons," says Peña. "We may be able to point back to July and say this is when it all started to unravel."

And if Bush does go down, Devine says many conservatives will refuse to be pulled along behind him. "His danger is if he gets in trouble," says Devine. "When you get in trouble you need the leaders to speak up for you, and the leaders are much less enthusiastic."

Still, he says, "As long as Bush stays in relatively good political shape, it probably doesn't make any difference."

At least, not right now. In the long term, though, Peña says it could lead the party to return to its roots. He compares the Committee for the Republic to the neoconservatives' Project for a New American Century, which formulated much of the Bush doctrine well before Bush took office.

"A lot of the people who are associated with the neocons got their start by doing the same thing" as the Committee for the Republic, Peña says. "They formed the Project for the New American Century and published their manifesto, 'Rebuilding America's Defenses.' You never know when something like that becomes something more than a group of guys meeting to kibbitz over policy."

If the party turns sharply away from nation building, that bodes ill not just for the reconstruction effort in Iraq, but perhaps for Republican political hopes in '04. "That rhetoric, as far as the democracy part, I don't know if even [Bush] believes that," says Devine. The problem is that the U.S. failure so far to find WMD means that the Bush administration has been forced to emphasize its idealistic, humanitarian motivations for the war. As a result, if Bush pulls U.S. troops out before Iraq is stabilized and the situation there spirals out of control, or anti-American fundamentalists take power, the entire adventure could end up looking pointless -- which would be a poison pill for Bush and his party. That's enough to wake any Republican up in the middle of the night.

Shares