When the White House announced its 10-year strategic plan for its Climate Change Science Program this July, the more than 300-page document could be summed up in two words: more research.

The plan's No. 1 priority is to study the ways that the climate varies naturally, as in, for example, the El Niño phenomenon. A secondary priority is to gather more information on human, or non-natural impacts on the atmosphere. Whether caused by burning fossil fuels, cutting down forests or belching industrial pollution, man-made effects on climate can be "quantified only poorly at present," according to the plan. So, to "reduce uncertainty" more data collection is needed.

It's a research agenda that enshrines the suspicions of global warming skeptics into federal policy: "Looking at the executive summary, I'm generally pleased with it," says William O'Keefe from the George C. Marshall Institute, a think tank that's received hundreds of thousands of dollars of funding from ExxonMobil. "The reason that they've focused on research is not a way to slow down taking action," he says. "Most of what we think we know about the climate system and human impacts on it comes from computer models that are based on hypotheses. There is a terrible deficit of real scientific information where you actually go out and gather data."

While the White House preaches the need for more study, more than 2,000 scientists from across the globe -- contributors to the U.N.'s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change -- have been in agreement since 1995 that human activities are contributing to worldwide warming. The United States' own National Academy of Sciences reported in 2001 that some of the warming of the Earth's atmosphere over the last 50 years is caused by greenhouse gas emissions, such as carbon dioxide generated by the burning of fossil fuels.

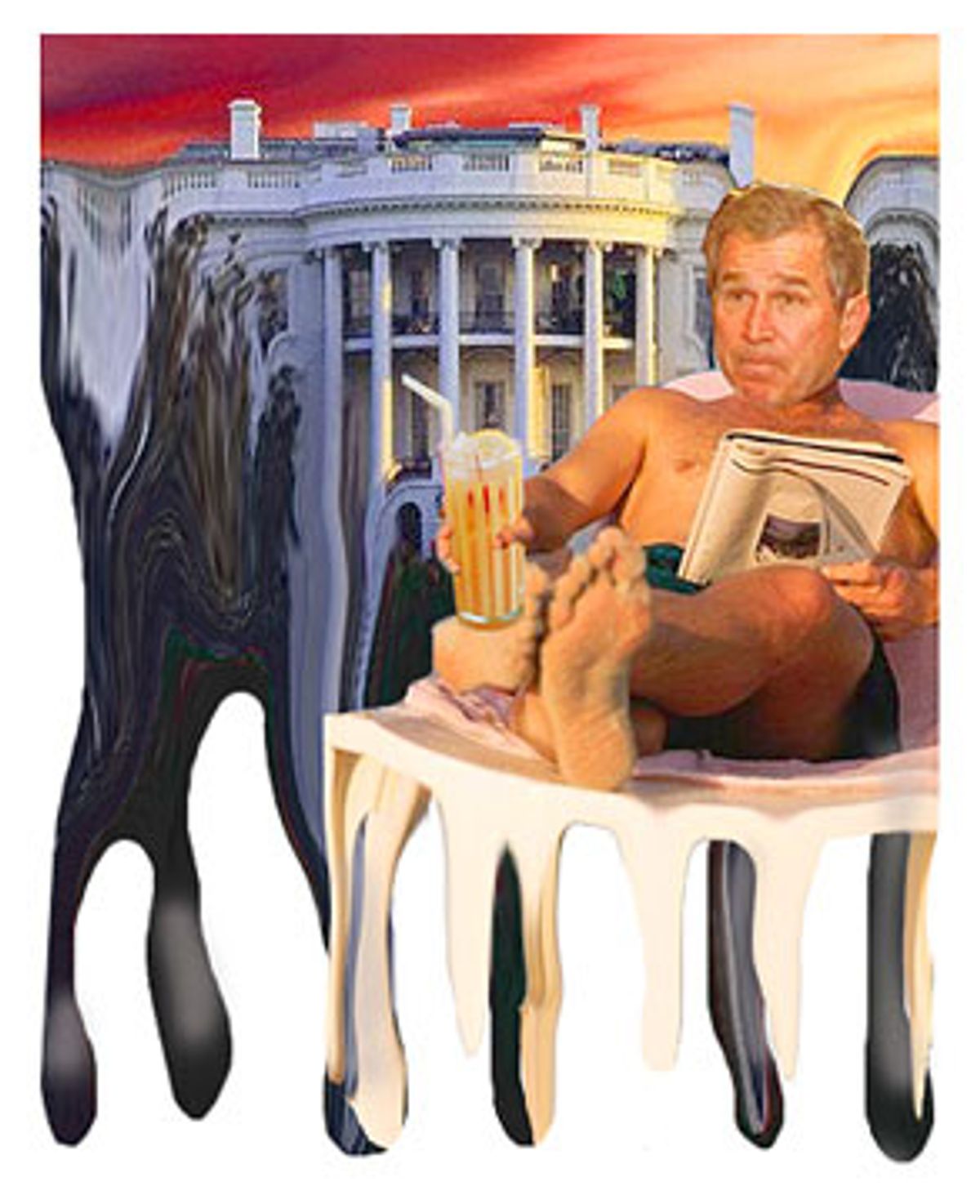

Environmentalists see the White House research plan as just another stalling tactic to avoid regulating pollution to mitigate global warming. "Most climate scientists around the world will see this as fiddling while Rome burns," says Philip E. Clapp, president of the National Environmental Trust.

For years, industry-backed global warming naysayers have claimed that the rise in global temperatures is not a real problem, is not caused by humans, and if it is in fact happening at all, it's actually good for the world. The Marshall Institute, for instance, began making that case in 1989, when it released a report arguing that "cyclical variations in the intensity of the sun would offset any climate change associated with elevated greenhouse gases." The view that nature would save us from ourselves was refuted by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, but was still influential with the first President Bush's climate policy, according to the Union of Concerned Scientists.

Now, more than a decade later, the new Bush administration is continuing to codify the naysaying view of global warming skeptics into government policy, counter to the growing consensus of most of the world's climate scientists. Their frustration is palpable: While more research is always good, they say, no amount of further study will change the fact that humans are in fact contributing to the warming of the planet.

"Ludicrous," is how Raymond Bradley, the director of the University of Massachusetts Climate System Research Center in Amherst, Mass., characterized the plan at a meeting of some 1,000 climate scientists in late July, reported on by the Associated Press. "Right now, we have good, strong scientific evidence supported by the vast majority of scientists who studied the problem to say we are facing a serious problem," he said.

Bradley charged that the White House is capitulating to "fringe science ... Politicians are always faced with making decisions in the face of uncertainty, but I think the uncertainty over this issue is relatively low."

It may be low among a preponderance of scientists who have spent their careers studying the problem, but their certainty isn't bending the ears of those who control the levers of power. The global warming skeptics, lavishly funded by precisely those corporations that have the most to fear from new regulations aimed at reducing emissions of greenhouse gases, have succeeded in perpetuating the notion that there's a genuine, ongoing scientific dispute as to the reality and causes of global warming. Fringe science is no longer on the periphery. Instead, it rules triumphant.

Before the November 2002 election, a Republican strategy memo warned party leaders that they should soften their message on the environment, recasting "global warming" as the more palatable "climate change," a phrase that sounds closer to what happens when you board a plane in Anchorage and get off in Houston than it does to some scary global crisis.

The now infamous Luntz memo advised that "voters believe that there is no consensus about global warming within the scientific community. Should the public come to believe that the scientific issues are settled, their views about global warming will change accordingly. Therefore, you need to continue to make the lack of scientific certainty a primary issue in the debate ..."

Administration officials looking for data to back the uncertainty theory haven't had to look far for sources of information. According to Ross Gelbspan, author of "The Heat is On," an investigative exposé documenting how corporate dollars influence the debate over global warming published back in the late '90s, there's a coal, auto and oil industry-funded cadre of professional skeptics and pundits that has been pushing the "uncertainty" line, with increasing success, for years.

The skeptics are sponsored by groups that include the Competitive Enterprise Institute, the Center for the Study of Carbon Dioxide and Global Change the Greening Earth Society and the George C. Marshall Institute.

"They manufacture uncertainty," says Virginia Ashby Sharpe, director of the Integrity in Science project at the Center for Science in the Public Interest.

Uncertainty about global warming is a view the White House unambiguously supports. Last September, a section on global warming in the annual federal pollution report from the Environmental Protection Agency was simply deleted, with White House approval. But it's not just inside the administration that these uncertainties find a receptive audience.

In late July, as senators debated the energy bill, Sen. James M. Inhofe, R-Okla., made a speech in the Senate calling for "sound science" to be the source of decision-making about global warming, while simultaneously asserting: "With all the hysteria, all the fear, all the phony science, could it be that manmade global warming is the greatest hoax ever perpetrated on the American people? I believe it is."

In his lengthy talk, Sen. Inhofe said: "After studying the issue over the last several years, I believe the balance of the evidence offers strong proof that natural variability, not manmade, is the overwhelming factor influencing climate, and that manmade gases are virtually irrelevant." To support this point of view, he cited, among other sources, a recent paper titled "Reconstructing Climatic and Environmental Changes of the Past 1,000 years: A Reappraisal" which concluded that the earth was actually warmer during the Middle Ages than it is now.

Inhofe called the paper "the most comprehensive study of its kind in history," but failed to note that the research was underwritten by the American Petroleum Institute, an energy industry trade group, and that four of the five coauthors of the study have affiliations with groups backed by oil, gas or coal money.

Astrophysicist Sallie Baliunas and physicist Willie Soon, both scientists at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, are also "senior scientists" at the Exxon-Mobil-backed Marshall Institute.

The father and son team of Sherwood and Craig Idso hail from the Center for the Study of Carbon Dioxide and Global Change in Tempe, Ariz., which has also received money from ExxonMobil. In the early '90s, Dr. Sherwood Idso narrated the video "The Greening of Planet Earth," which was funded by $250,000 from the Western Fuels Association, a coal-industry association, and according to Gelbspan, predicted that global warming will cause increased crop yields. In other words, global warming is good for us.

Sen. Inhofe complained in the Senate about the reporting of these energy-industry affiliations when the study came out: "Unfortunately, some of the media could not resist playing politics of personal destruction," he said. The senator himself has received some $543,269 in campaign contributions from energy and natural resources companies and PACs, more than twice as much as from any other category.

And, as reported in the Wall Street Journal, Hans von Storch, the editor of Climate Research, the journal in which "A Reappraisal" was published, recently resigned, along with two other top editors, to protest "irregularities" in the editorial process that allowed the paper to be published. But the fact that the paper itself is being widely criticized hasn't hampered its influence on policy.

Politicians in the White House and Congress, amply lubricated by energy money, don't deserve all the blame for the ascendancy of the global warming uncertainty principle. Part of the problem lies with journalists, says Gelbspan, a former reporter and editor himself.

Gelbspan criticizes reporters for constantly turning to energy industry-funded organizations for a "balancing" quote when writing about climate change. "This whole thing about journalistic balance: it's relevant when they're doing a story based on opinions, like abortion, but when it's a story based on fact there is no issue of balance involved at all," he says. "I think that the fossil fuel public relations people are really exploiting this misguided notion of journalistic balance, and the skeptics are taking advantage of it."

Gelbspan's critique is echoed by other representatives of the conservation movement.

"You'll find that their science fellows or adjunct board members or advisors or council of poohbahs always falls back to this handful of 'scientists' in this other category of people who have now made a living for the past five or 10 years on being skeptics on climate change," says Kert Davies, a research director at Greenpeace who has spent years tracking the funding of global warming skeptics. "If anybody wants a balanced story on climate, these knuckleheads get quoted, although we would say it doesn't reflect the balance of scientists."

While most climate scientists agree that the most general issues about global warming are settled -- Principally, is global warming happening? Yes. And do human activities have a role in it? Yes. -- there are unanswered questions that help the skeptics spread doubt.

"The only kind of skepticism that I would accept from a colleague would be the uncertainty in just how much of a role humans have versus other possible causes," says Michael E. Mann, a paleoclimatologist and professor at the University of Virginia, whose research on warming has been embraced by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. But what there isn't any lingering doubt about in the scientific community, says Mann, is that humans have played a role in the warming that's occurred in the last century.

The skeptics also play their own funding card when arguing that scientists have every reason to perpetuate the idea that there's a massive crisis building. Myron Ebell, the director of global warming policy at the Competitive Enterprise Institute, a conservative think tank that's received funding from ExxonMobil, the Ford Motor Company Foundation, General Motors Foundation, Texaco Inc. Foundation and others, claims that there are plenty of scientists who believe that this whole global warming crisis is "essentially bunkem," but "they won't speak up," since there's a gravy-train of federal money going to fund research projects in this area.

He casts the great global warming scare as a phony crisis manufactured by a bunch of chicken-little eggheads in search of funding for their pet research projects: "You've got to make noise now in order to get funding through Congress or the bureaucracy. If it's not some kind of crisis that the public cares about, it's not going to get funding," says Ebell, imagining the thought processes inside the mind of a money-hungry scientist brain: "'I've got to get people to notice me! I've got to have a crisis! Or, I'm not going to get any money, or not very much money.'"

The Marshall Institute's O'Keefe echoes that view. "I'm not saying that people are being dishonest," says O'Keefe. "I'm saying the system creates incentives for work that promotes more funding. 'If you give me more money I'll be able to show that.'" He blames the lingering influence of Al Gore for the climate gravy train: "In the early '90s, it was absolutely clear that the vice president of the U.S. had made a decision that there was a serious problem, and people who wanted to get government funding had to be generally consistent with the Gore view of global warming."

But now the research dollars are flowing under the Bush Administration for climate study, like the $103 million for the new Climate Science plan, precisely because of the uncertainty around global warming that groups such as the Marshall Institute have helped promote.

Another fact of climate science that helps the skeptics make their case is the reliance upon computer models for conducting research. Ebell scoffs at the climate models that researchers use to try to predict how much average temperatures will increase in coming decades: "As long as they put in junk assumptions, you're going to get junk out of the models." What we need, he says, is "more basic research to know what the problem is, and what it might develop into."

But Mann says that the computer models are a way of formalizing the questions that climate scientists are trying to test so that assumptions can be changed, verified and cross-validated. He points out that the skeptics who cast blanket doubt on such models want their own intuitive assumptions about climate studies to be trusted instead: "The irony often is that they will reject the models that we try to use to understand physical systems. They'll reject them in exchange for their own kind of unconstrained idea."

But beyond the real scientific questions that are still open, skeptics are able to take ample advantage of the larger fact that scientific debate is hardly ever definitively closed, once and for all.

"Science is always based on information that you have right now," says Sharpe from the Center for the Science in the Public Interest. "So, you can hardly ever say in an unqualified way that a debate has been definitively closed. Most scientific inquiry is based on the idea that it's always ongoing. The inquiry is always open."

"That is no reason for inaction in the face of strong evidence of significant harm. When the oil industry claims that 'the science is uncertain' on global warming and that voters should be made to believe that there is 'no consensus,' it is saying that we should not act on the basis of current evidence -- which unanimously links global warming with human activities -- except for those studies and opinions paid for by the industry."

Ironically, just last week there was evidence of an instance in which concerted action based on the best available science at the time paid dividends on an environmental issue. The destruction of the ozone layer has apparently slowed, thanks to the phasing out of chlorofluorocarbons that began with the Montreal Protocol in 1989.

"We enacted the Montreal Protocol to reduce the release of chlorofluorocarbons into the atmosphere with far less consensus than we've got on this issue. A third less science than this, and much less consensus," says Matthew Follett, the co-founder of the Green House Network, a grass-roots effort against global warming.

But maybe it's naïve to think that scientific consensus alone would force the U.S. to ratify the Kyoto Protocol, as it did the Montreal Protocol. With a raft of skeptics, backed by funding from the energy biz -- the largest industry in the world -- and politicians eager to embrace their skeptical views, there's always going to be more than enough "uncertainty" to put off doing anything until more data is available.

Shares