Day and night, ships arrive from around the globe at America's ports. Sealed steel boxes are hoisted from hulls onto waiting trains and trucks that roll to every state in the nation. Roughly 21,000 such containers enter the country each day, packed with millions of wooden crates and pallets. Along with their cargo, they can also hold invasive insects like the Asian long-horned beetle, which if it escaped to U.S. forests, could defoliate millions of trees and do billions of dollars in damage.

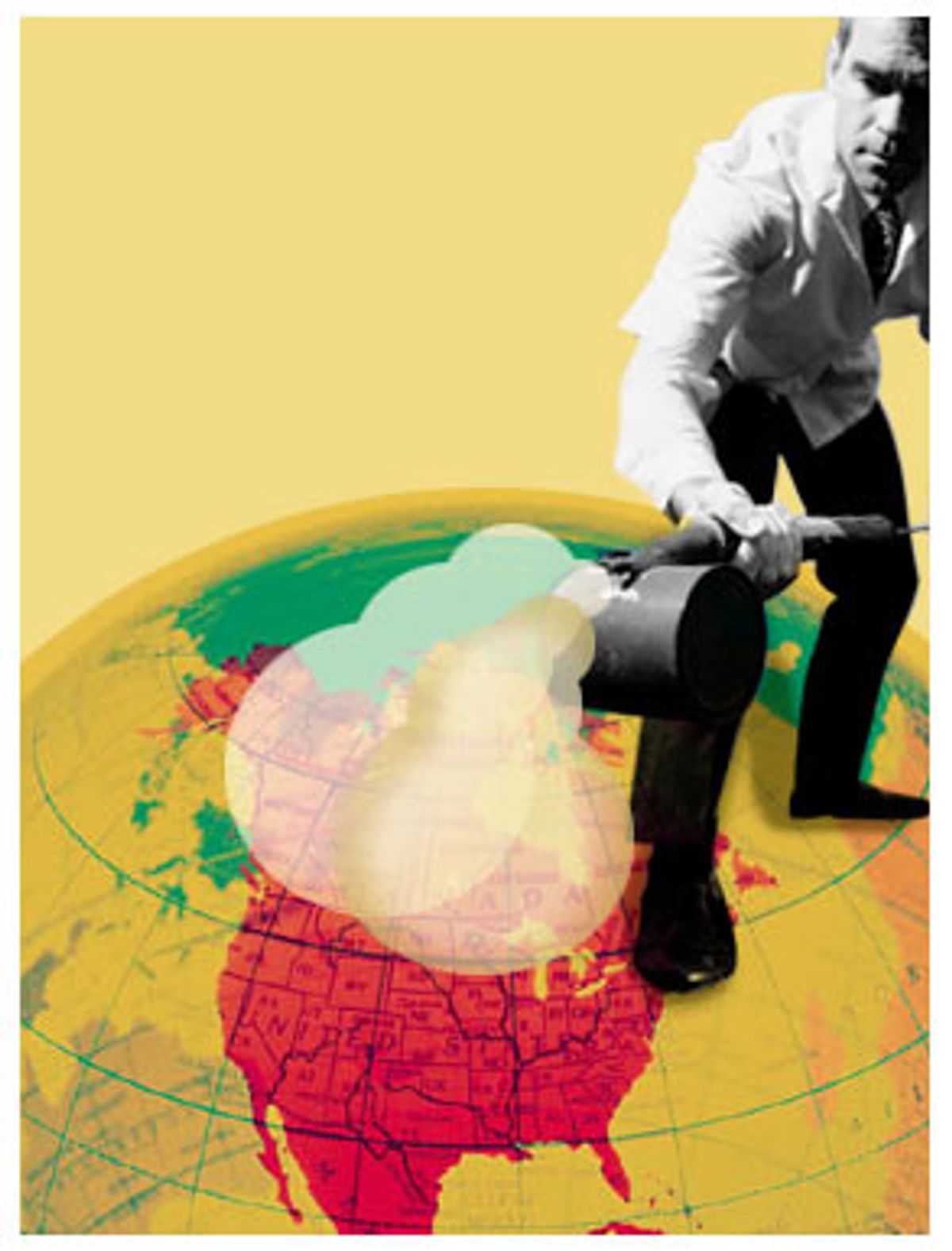

The Bush administration, to combat this very real problem, wants to force foreign countries and American ports to fumigate nearly every last board-foot with methyl bromide, a deadly pesticide. There's just one catch: methyl bromide is a direct, dangerous threat to the ozone layer, and because it's mandated for a total phaseout under both the Clean Air Act and the Montreal Protocol ozone-protection treaty, a massive production increase would violate both U.S. and international law. Bush's plan, which purports to benefit the environment, instead appears calculated to undermine the Montreal Protocol while wildly profiting some of the GOP's staunchest financial backers -- a handful of methyl bromide manufacturers and the agribusiness interests that are the biggest users of the chemical.

The Montreal Protocol has been called the greatest environmental victory in history and hailed as a triumph of international cooperation. Starting in 1987, the United States, under the Reagan administration, worked with 166 other nations, plus corporations like DuPont, to ban manmade chemicals that were allowing more deadly ultraviolet rays to reach the earth.

Now the Bush strategy could delay or even reverse the healing of the ozone layer, scientists say. It could derail the treaty itself, posing a significant health risk to humans and other life across the globe. The administration has launched a two-pronged attack on the protocol: A newly proposed rule by the Department of Agriculture would demand methyl bromide fumigation for nearly all imported raw-wood packaging, and the Environmental Protection Agency wants to allow U.S. farmers and businesses to use millions of added pounds of the poison on crops and golf courses.

"I think it is quite serious," says Don Wuebbles, a University of Illinois researcher who has studied the ozone layer for 30 years. "I would be concerned about anything that will lead to a potential increase of methyl bromide ... It's still one of the most important contributors to ozone depletion."

Methyl bromide is an odorless, colorless, little known but lethal agricultural pesticide. And its byproduct, bromine, "kills ozone something like 50 times more effectively than chlorine on an atom-for-atom basis," says William Randel, the senior atmospheric scientist at the National Center for Atmospheric Research.

The Bush initiative comes at a time when reports and studies show that, after years of concern and global action, Earth's protective ozone layer is starting to heal. Human output of chlorofluorocarbons has fallen dramatically; atmospheric levels of methyl bromide have been falling, too, as the phaseout of the chemical is beginning to take effect.

Just this month, the Christian Science Monitor reported that scientists have found "unambiguous evidence that Earth's sunscreen, the tenuous shield of ozone in the stratosphere, is slowly beginning to recover from nearly thirty years of human triggered loss." One key reason for the recovery, said the newspaper, is the declining use of methyl bromide, one of the most worrisome gases now threatening the ozone layer.

"Methyl bromide has decreased [in the atmosphere] more than 10 percent since 1998," Steve Montzka, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration scientist who made the discovery, told Salon. "We think the most likely explanation of where that decrease in atmospheric methyl bromide is coming from is due primarily to the Montreal Protocol restrictions on its production."

If all human production of methyl bromide ceased today, says a 2002 World Meteorological Organization scientific assessment, global ozone depletion would be reduced by 4 percent. That doesn't sound like much, but a total ban could curb harmful ultraviolet rays, cutting non-melanoma skin cancers by about 8 percent and eliminating up to 600,000 cases of cataract-induced blindness annually, according to the United Nations Environment Program.

Under the Montreal Protocol, methyl bromide production has already been curtailed by 70 percent of 1991 baseline levels, with a total ban due in 2005. But by playing a cagey numbers and lawyers game with the treaty, the administration hopes to keep the chemical in use at high levels after the phaseout date both in the United States and abroad, pleasing its agribusiness patrons while maintaining the appearance of staying within the letter of the law.

"There is no question that this is a case of another big polluter, of an industry well connected to the administration -- just like coal or oil -- looking for multimillion-dollar favors," says David Doniger, policy director of the Climate Center of the Natural Resources Defense Council. The new rule proposed by the U.S. Department of Agriculture to fumigate all raw solid-wood packaging shipped into the United States, could skyrocket global methyl bromide production. (While heat treatment is a suggested alternative, its higher cost would likely result in methyl bromide being the method of choice.)

The department says it is merely implementing a mandate of the U.N.'s International Plant Protection Convention, agreed to by 118 nations. But that agreement offers only guidelines, not strict rules, and it allows for multiple forms of treatment, including the use of chemicals that wouldn't damage the ozone.

The Agricultural Department concedes that its universal fumigation plan could raise methyl bromide's use from current global levels of roughly 55,500 metric tons to as much as 158,500 metric tons. That worst-case scenario could triple production of the pesticide worldwide, and in the department's own estimation, increase human-made methyl bromide emissions by a staggering 155 percent, enough to cause significant harm to the ozone layer. The Agriculture Department did not respond to several requests by Salon to speak with the lead scientific author of this damning report. However, the agency insists that this scenario is unlikely.

Unfortunately, if the department approves the new rule, it will have almost no control over the amounts of methyl bromide actually used, since most fumigating would occur abroad, before shipment. The U.S.-imposed regulation could also force developing countries to use far more methyl bromide than they now need, hampering their efforts to cut future use of the chemical as required under the Montreal Protocol.

Typically, treaty exemptions must be approved by the U.N. Ozone Secretariat, the Montreal Protocol's governing body, but a loophole allows the Agriculture Department to put its rule into practice without such approval. That's because quarantine and pre-shipment applications for invasive-pest control accounted for a minuscule amount of methyl bromide use in the past and weren't banned.

"What you have is a situation where the quarantine use was a small but important one, the tail on the dog," explains Doniger, of the Natural Resources Defense Council. "What the Montreal Protocol parties decided to do was phase out the dog -- the many agricultural uses for methyl bromide -- and live with the tail. Now the Bush administration wants to reverse the situation. Under the Department of Agriculture proposal, the tail will become three times larger than the dog."

The Agriculture Department admits in its environmental assessment that its strategy, while putting the ozone layer at risk, may not even be effective. Some bugs will survive methyl bromide fumigation, and even a few will be harmful since they can multiply, eventually ruining crops and ecosystems. The department even admits to better alternatives. One surefire approach would be to ban all raw-wood packing, a viable global goal if done over a reasonable transition period.

The Agriculture Department isn't the only agency spurring methyl bromide production. The Environmental Protection Agency is seeking methyl bromide "critical use" exemptions at the U.N. Ozone Secretariat meeting in Nairobi, Kenya, in November.

The EPA, reportedly under pressure from the White House and Agriculture Department, wants exemptions to raise methyl bromide use by 39 percent above 1991 baseline levels for 16 crops, including strawberries, tomatoes, ginger, sweet potatoes and turf grass. The agency says there is no technically or economically viable alternative for these crops. If granted, these exemptions alone would stop and reverse the pesticide's total phaseout in 2005.

While EPA claims its exemption request doesn't violate the letter of the law as stated in the treaty, Doniger, a Clinton administration diplomat, disagrees. "What we negotiated in 1997 was a total global phaseout of methyl bromide in four steps, [reaching] a total phaseout in 2005," he told Salon. "An exemption was included, in that last step, that allowed continued production for 'critical uses,' in order to help the manufacturers and users achieve a soft landing before total phaseout."

But the Bush exemptions, if approved, would roll back a 70 percent methyl bromide reduction already in place, to a 61 percent reduction. Instead of a total ban, it would permit the manufacture of 10,000 metric tons of the pesticide, not counting the Agriculture Department's quarantine and pre-shipment request.

"If the Bush administration interpretation of the treaty were followed, the parties could agree to any amount of exemptions," says Doniger. They could raise production all the way back "to 100 percent of each country's 1991 baseline," he adds. "This is an absurd reading of the protocol." The U.S. also wants an added exemption in 2006, a contingency not ever addressed by the treaty.

The EPA says that its exemptions "reflect a downward trend," but anyone doing the math can see that the U.S. is asking for a 9 percent increase over current production. When asked whether Salon's math was correct, Drusilla Hufford, director of the global programs division at EPA, skirted the question repeatedly.

"We are absolutely not in violation of the Montreal Protocol," Hufford asserts. "I think that looking at it as a setback is a mistake. It isn't an appropriate question to ask ... We have conducted very successful phaseouts of a number of chemicals that included this kind of policy approach." True, the phaseout of other ozone depleters allowed exemptions, but not of such massive proportions. For example, a tiny exemption for chlorofluorocarbons was allowed for personal asthma inhalers.

When asked when a total ban of methyl bromide might happen, Hufford said: "I really couldn't predict that."

Doniger worries that the Bush administration request, if approved by the United Nations, may weaken the will of other nations. "If the United States backs out of its methyl bromide phaseout, you could see the developing countries balking not only about phasing out methyl bromide, but other chemicals as well. Why should they go to strenuous efforts to get rid of [them] ... when America isn't meeting its commitments? We could see the whole treaty unravel."

Josh Karliner, a board member with Corporate Watch, an anti-globalization activist group, expresses another worry about a failed ban. "This is also a Homeland Security issue. A few weeks after 9/11," he says, "I got a call from the Coast Guard wanting to track down information on methyl bromide production and distribution because it is a highly toxic, colorless, odorless gas. This is not the kind of chemical you want to be freely proliferating at this dangerous time in history."

EPA claims that there are no viable alternative to the pesticide. But as long ago as 1995, a U.N. scientific panel concluded that alternatives to methyl bromide were either available or at an advanced stage of development for more than 90 percent of methyl bromide uses. That puts the lie to an EPA claim that there has been insufficient time to approve substitutes.

That's also a far cry from a methyl bromide industry claim that farmers worldwide have absolutely no "effective alternatives" to the poison, reports Corporate Watch. It is to those industries -- the methyl bromide makers, users and lobbying groups -- to whom one must look to understand the Bush administration's attempt to backpedal on its treaty commitments.

Just three companies dominate 75 percent of all methyl bromide production: U.S.-based Albemarle Corp. (a spinoff of the Ethyl Corp.), along with the Great Lakes Chemical Corp. and Israel's Dead Sea Bromine Group. They make up what the Chemical Marketing Reporter calls "the global bromine industry oligopoly." Both U.S. companies have poor environmental records: Albemarle has been fined nearly a million dollars for violations since 1993, while Great Lakes Chemical was rated Arkansas' worst polluter during the 1990s, based on annual federal Toxic Release Inventory Data, says Corporate Watch.

In truth, methyl bromide might have been disposed of as toxic waste had not the companies contrived its use as lethal pesticide. Methyl bromide is a highly poisonous byproduct in the manufacture of a popular flame retardant, tetrabromobisophenol-A (TBBA), used increasingly by the computer industry. As demand for TBBA grows, so does the amount of toxic methyl bromide resulting from the industrial process, as does a need for the companies to sell or dispose of it.

Besides its ozone-depleting characteristics, methyl bromide is designated a Class 1 acute toxin by the EPA, with a reputation for killing humans as well as insects and weeds. It's been used for 50 years to sterilize soils prior to the planting of crops. Injected into the ground, it kills virtually every living thing, good or bad. It's also used to fumigate fruits, vegetables, dried nuts and grains before they're sent to market, and to fumigate homes, warehouses and grain elevators. The exposure of humans to it can cause nausea, chest pains, numbness, convulsions, coma and death. The U.S. National Cancer Institute recently linked methyl bromide to increased prostate cancer in product handlers. Farm workers and environmentalists have sought a ban for decades.

Which is perhaps why the methyl bromide makers and users are such generous political patrons. For example, the Floyd D. and Thomas E. Gottwald family of Virginia, controllers of Albemarle and Ethyl corporations, gave roughly $345,000 in the 2000-02 election cycle to the Republican National Committee, the Bush campaign, GOP congressional candidates and others, according to the Center for Responsive Politics.

Methyl bromide producers and agribusiness interests belonging to the influential Crop Protection Coalition have vigorously fought the ban on methyl bromide, while giving $2.3 million in political contributions in the 1990s, according to Common Cause.

From 1990 to 2002, agribusiness gave more than $203 million to Republican candidates and $93 million to Democrats. George W. Bush received $2.7 million for his 2000 campaign from the industry, while Al Gore culled just $314,000. Agribusiness contributions to the Bush 2004 campaign, at $697,000, already nearly equal those of energy and natural-resource interests ($736,000), likely assuring both sectors continued favor in the Bush-Cheney administration.

The Center for Public Integrity in its report, "Unreasonable Risk: The Politics of Pesticides," relates how Texas Republican Rep. Larry Combest paraded the Crop Protection Coalition's 35 member groups through a 1998 congressional hearing, then decided in favor of the absolute necessity of the chemical: "We have no proven cost-effective substitute for methyl bromide," he said. "Methyl bromide is an essential tool for many aspects of our modern agricultural industry." Combest received about $196,000 in contributions during the 1998 election cycle from agribusiness, plus another $320,000 in 2000.

House Majority Leader Tom DeLay has strong agribusiness connections, as demonstrated by his support for the industry -- and by his campaign war chest. A pest exterminator by trade, he has fought all Clean Air Act amendments since 1990, especially those attempting to ban methyl bromide. When ozone-depletion researchers won the Nobel Prize in 1995, DeLay said: "I am puzzled at how the Swedish Academy of Sciences could award to these professors the Nobel Prize in chemistry for theories that have yet to be proven." He then accused Sweden of being "dominated by the agenda of radical environmentalists" and derided the award as "the Nobel appeasement prize," according to Global Change magazine and the Sierra Club. During that election cycle DeLay accepted $108,900 in contributions from agribusiness.

Political contributions seem to have brought dividends to the industry, along with the occasional grand jury investigation. While he was California's governor, Republican Pete Wilson received $190,000 in campaign contributions from 1989 to 1996 from Sun-Diamond Growers of California, a major methyl bromide industry player, according to the San Francisco Chronicle. As governor, Wilson worked diligently to delay, then prevent, a statewide methyl bromide ban, even though the pesticide had killed 19 California residents and poisoned 400 since the early 1980s, according to the San Diego Union Tribune. The poison is still legal there even near schools and homes.

In 1996, a federal jury found Sun-Diamond guilty of offering thousands of dollars in illegal gifts to Clinton administration Secretary of Agriculture Mike Espy (the unfolding of the scandal had caused Espy's resignation in 1994). According to the grand jury, one of the things Sun-Diamond sought was the help of Espy and the Agriculture Department in persuading the EPA not to ban methyl bromide, reported the New York Times.

As evidence comes in demonstrating the atmospheric healing power of the methyl bromide phaseout, the U.N. Ozone Secretariat remains silent about how it will respond to the EPA exemption demand at the November Nairobi meeting. America stands nearly alone in its large request, with only Italy and Greece seeking large exemptions. How the protocol parties will respond to the Department of Agriculture's abuse of the quarantine and pre-shipment exemption is also unknown.

However, a U.S. response to any opposition offered by the secretariat is less in doubt. Should America fail to get its exemptions approved, House Energy and Commerce Air Quality Subcommittee chair Joe Barton, another Texas Republican, stands ready to create a legislative fix that would allow the continued production of methyl bromide, putting the United States in direct violation of the Montreal Protocol, according to the Environment and Energy Daily news service.

The "Barons of Bromide," as Corporate Watch calls Albemarle, Great Lakes Chemical, Sun-Diamond and other methyl bromide purveyors, are brokering for a big boost in business, even at the cost of an international treaty crisis. If they and the Bush administration succeed in cowing the Montreal Protocol parties, their strategy could keep methyl bromide on the market forever, or at least until the ozone layer fails.

Shares