Snoop Dogg is backstage at "Late Night With Conan O'Brien," and he's cradling a little blond boy in his arms. The boy is comedian Andy Richter's son, and Richter's wife wants a photo of him with the world-famous hip-hop star, the man synonymous with the term "gangsta rap." Snoop -- who's making talk-show rounds to promote his latest album, "Paid Tha Cost to Be Da Bo$$," and his MTV comedy sketch show, "Doggy Fizzle Televizzle, " which wraps its first season this month -- scoops up little Richter. It's a shot for the family album: Snoop, in Converse sneakers and baggy Snoop Dogg Clothing sweats, with a little white boy in a wide-eyed grin.

Later, Snoop poses for another camera. Slumped in Conan's hot seat, he details the burgeoning conglomerate that is Calvin Broadus, aka Snoop Dogg: his clothing line; his DoggyStyle Record label; his soul-inflected recent album and his first love song, the hit single "Beautiful." There's Doggyland theme park, soon to open in Mississippi, and the special-order Snoop DeVille, a mink-seated Cadillac low-rider (which he deems "fit for a pimp"). There's "Doggy Fizzle Televizzle," in which Snoop mesmerizes a first-grade class with Iceberg Slim as if it's Doctor Seuss. When Conan whips out a Vital Toys Snoop doll, the rapper interjects. "Not a doll. An action figure," he declares, adding that his boys like to pit him against Batman and Robin.

Next, Conan jokes about a certain sweet scent that, back in the day, emanated from Snoop's dressing room, but the rapper is deadpan. Quitting his "thousand-dollar-a-day" marijuana habit in order to be a better coach to his son's football team and a role model to his fans is, he insists, no publicity stunt. Snoop first told me he quit because one of his musical idols and close friends, Johnny Wilson of the GAP Band, told him to; days later he added, "It's hard to have a clear head, to put in that quality family time, if you're always high."

The mantra coined by Snoop's omnipresent publicist, Richie Abbott, goes like this: "Snoop's for the kids." I hear it often during our trip from L.A. to Las Vegas with Snoop, who'll be ad-libbing prank phone calls as a guest on Comedy Central's "Crank Yankers." The tour bus is outfitted with strobe lights, black leather seats and bottles of Hennessy, but Snoop could care less. He's holed up in the back of the bus with fast food, a Kung Fu video and PlayStation.

In the "Crank Yankers" studio, Snoop enjoys the wholesome mischief of prank calling, keeping us in stitches, after the job is done, with calls to friends like Dennis Rodman. He's almost too soft-spoken to pull off a prank: When words like "bitch" (or, in his slightly Southern twang, "bee-atch") slip sweetly from his lips, Snoop might as well be murmuring "baby."

But as the show's team scribbles prompts on poster board, holding them up as guides for Snoop while he makes his calls, I wonder if they've been informed that Snoop is now "for the kids." For one skit, Snoop is instructed to phone a high school principal and tell her he'd like to lecture students about drugs. Following the principal's stunned initial response -- "You want to come here? To our little town?" -- staff scribbling begins. "Ask about the weed she likes," reads one poster board. "Can she let you hand out rolling papers?" "Gin and juice?" "School gangs?" "How's her butt?"

After two hours in this sea of gangster clichés, Snoop is transported from the studio in a swarm of bodyguards who can never leave his side -- especially at the local mall, where Snoop decides he wants to meet the saleswoman he'd prank called. The shopping spree becomes a quasi-riot when word spreads that Snoop is in the vicinity, and the shop owner closes his gates as Snoop models Roca Wear jackets. Crowds gawk through the iron gates as if ogling the top attraction in a zoo.

Hoping to make Snoop's son's afternoon football game, we finally file into a homeward-bound bus. Snoop tries to wander off.

"Where do you think you're going?" one bodyguard calls after him. Snoop keeps walking. "Over there," he says with a frustrated sigh, pointing at the McDonald's across the road.

"Not alone, you're not!" comes the reply, as it seems to have come many times before. Faster than you can say "Big Mac," Snoop's security team are on his tail. They're always on his tail. They were on his tail in April, when -- for the third time in his career -- Snoop found himself in the line of fire, the target of a loaded gun.

As Snoop's long, lean figure disappears in the dawn, a timeless question springs to mind: Can an old Dogg learn new tricks? Once upon a time, Snoop was gangsta rap's golden-tongued child. His mesmerizing delivery, so tranquil it could rival Mr. Rogers', belied its subject matter: juice-and-ginning, Crip walking, the bitch in his bed last night. His brand of hip-hop -- its images of young black men in low-riders, sporting gang colors and proclaiming "fuck the police" -- first put South Central Los Angeles on the musical map in the late '80s, then rode the wave of '90s culture wars by prompting FBI warnings, nationwide boycotts, and courtroom dramas. A decade after gangsta rap's heyday -- after Snoop's "Doggystyle" sold 802,000 copies in its first week and was the first debut album to ever enter Billboard at No. 1 -- the 31-year-old Snoop, declaring himself a family man, tries out a public rebirth. But with five albums, a gangsta-hungry fan base, and a real-life gangster history, can a gangsta rapper really move on?

-----------------------------

There's a knock at the door of Snoop's dressing room at "The Jimmy Kimmel Show," where Snoop is co-hosting for a week. No one wants to answer because everyone knows who it is: theater security, requesting yet again if, please, could Snoop's people put out the blunts, please? The smoke has drifted down the hall.

There's smoke for every inhaler in Snoop's sizable, wide-ranging entourage: old friends from his hometown, Long Beach, Calif., many of whom work in one form or another for DoggyStyle Records; a coterie of middle-aged, silk-shirt-wearing avuncular types with names like Uncle Charlie Wilson and June Bugg (who's actually Snoop's uncle); at least a handful of bodyguards, some of whom have been with Snoop almost a decade. Midriff-baring ladies keep all the men in rollicking moods.

In the corner of the room, oblivious to the hubbub surrounding him yet somehow defined by it, is Snoop. He's having his hair braided by a woman who materializes every time Snoop needs a new look, which is often: The rapper travels with an inexhaustible supply of sweat suits and Converse sneakers. One eye on me, the other on his PlayStation, Snoop answers questions efficiently, as if he's been well trained by publicists over the years. He sums up his evolution neatly: "In 1993 I was restless. I had no cares, no kids, and I was enjoying the limelight. 2003 is about my kids, my wife, my bettering myself, and trying to be more of a role model."

His friends are excited about this evolution. They say he's the same-old Snoop, just older and wiser. "Quitting weed? That ain't no image change. That's positive change for his health," says a singer called Lil' Half Dead, who's known Snoop since childhood. Rapper Kam, also a longtime friend of Snoop's, nods. "He's an institution now, not an individual. Whether we want it or not, we're role models." His wife Shante -- who began dating him after he walked up to her at a high school football game and told her she was pretty ("Because there was just something funny about him") -- says football helped turn around Snoop. "Ever since he started coaching our son's team, he's just more devoted."

After the Kimmel taping, Snoop, a little less pre-packaged, holds a blunt in his long fingers. And yes, he's inhaling: Though he first quit cold turkey, Snoop now smokes on special occasions (and plenty an occasion seems special enough). When I tell him he makes a good talk-show host, he's all ears. "You think so?" Snoop asks, almost breathless. I suggest it's because he's a tolerant guy who can calmly take in varied personalities -- even ones like Tammy Faye Baker, Kimmel's guest tonight. He stares at me for a moment, in rapt attention. "I like her," Snoop nods. He also likes Bill Clinton ("I miss you, Bill. Let's make a record together," he says), and insists the world needs more role models. "Who?" I ask. Snoop stares again. "Me," he replies softly, as if the question were rhetorical. "I've seen a lot. I can be a leader." But what, I continue -- he's glowering at me now -- about headlining L.A.'s annual pro-pot concert last November, or being named High Times' "Stoner of the Year"? What about lyrics that still find him, "gin and juice in hand," Crip-walking up a storm?

Snoop is suddenly that L.A. archetype, a reformed gangster. "You gotta understand that people can relate to it because I actually lived that lifestyle, so it's not a preach-and-teach routine. I can make people say, 'Well, I don't have to do it because Snoop did it for me -- and I see the results of him doing it but also the results of him doing better.'"

America -- a country built by Puritans who were fixated on reform -- has long loved converted sinners. It adores, too, bad boys with soft spots -- which is probably why a rapper's most fashionable accessory these days is a child. Eminem's high-profile daughter Hailie represents our rebel's ultimate goodness, his potential for reform.

Snoop's favorite song on "Paid tha Cost to be Da Boss" is "I Miss That Bitch" -- in which said "bitch" is marijuana -- because "when I wrote that song, I was really missing weed bad. But I knew I could quit." Asked to describe himself in a word, he offers three: "standup kinda guy."

Only "Jim Henson's Muppet Christmas Special," which Bill O'Reilly's fuss got him edited out of last year, seems to hit a chord. "I can't believe [O'Reilly] did that, and he let millions of kids down," he says quietly. "They love me."

Snoop turns away in disgust, passing the blunt to his "spiritual advisor," Archbishop Don "Magic" Juan. Juan, sipping from a bejeweled goblet and wearing a white suit with a dollar-bill pattern, is a former pimp who earned ordination. Decked out as Dolemite, he's the rapper's unofficial mascot.

"Snoop is calmer now, baby," Juan shouts at me above the din, waving smoke from my eyes with a gold-encrusted hand. "Millions have seen it. They saw it at the Playboy mansion, when we visited there together. His family life has improved, and he's reaching a spiritual level that he couldn't reach before because his brain was clogged up with weed and alcohol. That's why his career is taking off the way it is, why he's touring with those -- what's their name? -- Hot Chili Peppers, and with 50 Cent."

Juan helped Snoop prepare for his role as Huggy Bear in the upcoming remake of "Starsky and Hutch," starring Owen Wilson and Ben Stiller. Says Snoop, "The music side is so natural for me -- it's creative in the natural sense. But the movie thing pushes me. It drives me to become another character, to do things I might not do." Snoop has already flexed his gangsta muscles in John Singleton's "Baby Boy" and smoked chronic alongside Dr. Dre in "The Wash." The latter is an over-the-top comedy about South Central L.A. that, like Ice Cube's recent "The Friday After Next," is starkly different from what critics called "new black realist cinema," which pervaded Snoop's early days in rap: "Boyz n the 'Hood," "Menace II Society," and "Poetic Justice." At the film premiere party for "The Friday After Next," food was served by jovial waiters sporting gang-style bandannas.

Between inhales, Juan is still talking. "Everybody's always pullin' at Snoop Dogg, but I try to do for him. I go get him things, like a fish fillet -- I know he like that. Orange Crush -- he like that, too. And because of my association with Snoop, I'm taking myself to new heights. Like -- and you print this -- I'm the first pimp William Morris ever signed!"

In videos and songs with titles like "P.I.M.P" and "Pimp Juice," in a VSOP liquor commercial, Snoop and Juan have lately been inseparable. Describing himself on one album track as "Snoop Hefner mixed with a little bit of Dogg Flynt," Snoop also does ubiquitous solos in college-as-bacchanalia cinema -- "Girls Gone Wild: Doggystyle," a DVD advertised on the E! channel, as well as "The Real Cancun," reality television's big-screen debut. He sports lavish furs and a pimp's cup, hamming it up in Rabelaisian glory.

In person, he's sometimes in blaxploitation mode: Big Snoop Dogg, whose verbal ticks include lines like "you got's to do it!" and "the game is calling me, baby!" and who uses the suffix "izzle" to produce a lexicon of slang (as in, "for shizzle, my nizzle," loosely translated as "for sure, my man"). During my first encounter with him, Snoop drove up in a blue Porsche, wearing the sort of incognito getup -- a colorful headscarf and enormous sunglasses -- that hides little, especially on a 6'4" celebrity. Unfurling himself from the car, Snoop gave me the once-over, licked his lips, and sweetly purred, "Where are you from, baby girl?"

"Personally, I don't care too much for that side of him, but hey, if it floats his boat, it's fine," Shante says of her husband's Superfly routine. "I just don't get it -- all the weird clothes and bright colors. I'm tolerant, though. Snoop tells me that every day."

Shante may be married to Calvin Broadus but she's also married to Snoop Dogg -- who has both enemies and permanently affixed bodyguards. Snoop's security team won't say how his three L.A.-area homes are protected, only that they are protected. "Sometimes I think, Can't we just take a trip to Disneyland, just the five of us, and not have all the security? But that's just the lifestyle we live. Even the kids are used to it now," sighs Shante.

Security is something other gangsta rappers know well. "A person like me with a past like mine -- I live in a weird state of paranoia," says Ice-T, one of the first gangsta rappers and a former pimp. Speaking with professorial gravitas about "the science of the gangster," Ice-T -- now 43 -- sits in his Manhattan high-rise, nostalgic for his Crip-walking days, compulsively miming the gang dance that Snoop's rhymes made famous. "I guess I'm what you would call hyper-sensitive, like a cat or predator in the jungle. I see everything. My instinct is the only thing that's gonna keep me alive. I have a nice street level of fear that I turn into awareness. I call it being on point. I don't get high, because I always want to be alert. You've got to be ready for whatever."

Late last year -- when Snoop first started talking reform, when it hit home that Ice-T had gone from peddling drugs in Compton to peddling "Posse Pops" ice cream -- many heralded the triumph of time and money over something America once shunned: gangsta rap. A genre of hip-hop born in the late '80s, gangsta rap -- which some prefer to call "reality rap" -- sprouted first on the East Coast with artists like KRS-One, then blossomed on the West Coast, where two acts took it national: Ice-T and NWA, or Niggaz With Attitude. Their 1988 album "Straight Outta Compton" -- too controversial for MTV or radio -- went triple platinum, established the theme and funk-backed sounds of the genre, and sent five teenagers from Compton to stardom: Andre Young (Dr. Dre), O'Shea Jackson (Ice Cube), Lorenzo Patterson (MC Ren), Eric Wright (Eazy-E), and Antoine Carraby (DJ Yella).

At its best, gangsta rap sustained the tradition, reaching back to '70s political poets like the Watts Prophets, of voicing the young, poor, and black in L.A. At its worst, it devolved into tawdry trappings of gangsterism -- misogynistic, violent posturing whose redeeming value was its putative realism -- or meta-rap, which didn't say something profound, political, or controversial but kept asserting that it could do so.

In 1992, a former bodyguard from Compton, Marion "Suge" Knight, secured backing from Interscope Records to establish Death Row Records, which immediately signed Dr. Dre and his protégé, a young rapper from Long Beach named Snoop Doggy Dogg (he's since dropped the "Doggy"). Like his favorite rapper, Slick Rick, Snoop wrote rhymes that were often comic; his moniker evoked a cartoon, not a cartel. But though Knight liked to think of Death Row as the Motown of the '90s, squeaky-clean Motown made black performers presentable to white audiences while Knight and Death Row generated over $100 million a year doing the opposite: Knight supposedly encouraged his legendary trio -- Dre, Snoop and Tupac Shakur -- to play up their gangsterism in every verbal and visual way possible.

This stoked the ire of Bob Dole, William Bennett, and C. Delores Tucker, of the National Congress of Black Women. In 1993, Tucker feasted her eyes on lyrics from "Doggystyle" and launched a crusade against Snoop and gangsta rap. Her 1994 statement in Sen. Carol Moseley-Braun's Senate hearings deemed Snoop's music "pornographic smut"; in 1995, her hullabaloo -- and hefty chunk of company stock -- succeeded in getting Time Warner to dump its share of Interscope, Death Row's distributor. Snoop was, as Tucker put it in a recent phone chat, "committing genocide on our children, and I had to stop him." Snoop is now Tucker's victory medal. "They're stopping all that gangster business now. Rappers are turning gospel," she asserts.

Gospel? Not quite, but Tucker has a point. Dr. Dre, mastermind of "The Chronic," an album that is to gangsta rap what "Ulysses" is to modernism, has long denounced any association with the genre; he's now the legendary producer behind today's top two rap acts, Eminem and 50 Cent. Ice Cube, who voiced the ire of Rodney King's L.A., who once added a verse to rap group Public Enemy's "Burn, Hollywood, Burn," is -- thanks to the hit movie "Barbershop," which grossed more than $80 million, and his Cube Vision Films -- Hollywood royalty. Ice-T has gone from singing about a "Cop Killer" to playing a cop on "Law and Order: SVU." Only Snoop still calls himself a gangsta rapper.

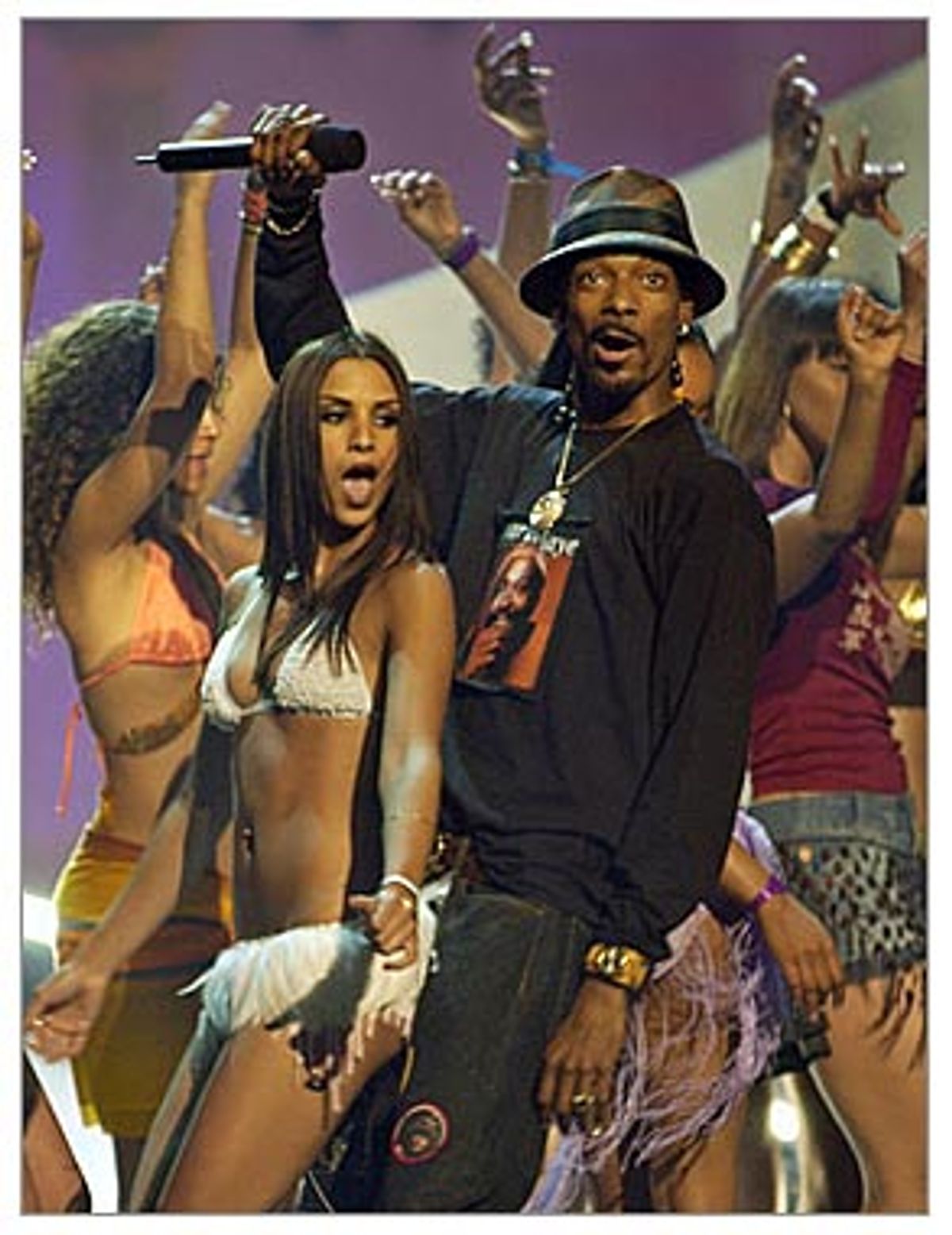

At a taping of MTV2's roving "$2 Bill tour" in Louisville, Ky., fans have lined up to see this gangsta rapper. The diverse crowd is the sort that MTV manufactures: old and young, black and white, industry and non-industry. Snoop takes the stage in a red football jersey and gray sweats, backed by a live band and backup singers who exhibit the more mature, soulful side of his new album. Snoop never sweats. In his signature style, he calmly ambles to and fro, enunciating rhymes as if conversing with his audience. Then Snoop begins a sentence with, "Now that I've quite drinking and smoking." The audience boos; Snoop sighs. He revises his statement: "OK, OK -- I still drink and smoke." The crowd roars. Among them is a blond girl in a Kangol hat and low-cut sweater, who joins Snoop in a merry chant of "Fuck the police."

At the Snoop Dogg Clothing Co. warehouse in Manhattan's fashion district, head designer Guka Evans showcases the spring line. He lays out several oversized plaid shirts, matching khakis and two basketball-style jerseys. "These are the two Snoop personalities: the West-Coast casual aesthetic, and the more aggressive, athletic feel. During our first season, the retro-West-Coast look was the biggest seller," Evans explains. There's a tank top with "pimp" across the chest and a "Snoop All Stars" top that reads "Hoopdog." Among the rejects is a shirt with "1-8-7" printed on it; it's inspired by Snoop's duet with Dr. Dre, "Deep Cover," about putting "1-8-7 on an undercover cop" (the municipal code for homicide). Designers had the shirt reprinted with "2-1-3," instead, which is the Long Beach area code and the name of Snoop's first rap group. "We didn't think Macy's would be too happy with that one," says CEO Michael Cohen, pointing at the reject with a nervous laugh.

No one was laughing on April 10, when Snoop was driving his brown custom Cadillac ("brown sugar," he calls it) south on Fairfax Avenue in L.A. and a northbound sedan fired nearly a dozen shots in his direction. They missed Snoop, but a bullet grazed one of eight bodyguards trailing him in five surrounding vehicles. An anti-gang LAPD unit heard shots and arrived on the scene; after questioning, Snoop was carted off safely in an armored vehicle. Either because it was utterly in line with the same-old Snoop -- or puzzlingly out of line with the new-and-improved one -- the incident remained relatively low profile, and no arrests were made.

According to Juan, whom Snoop had been visiting that night, the shooting was a product of young boys who tried to approach Snoop and were brushed aside by security. Rumor mills produced a juicier suspect: Suge Knight, gangsta rap's longtime scapegoat. Knight and Snoop have been publicly feuding ever since Snoop left Death Row in 1998, while Knight served a five-year jail sentence for various parole violations. Snoop insults Suge on "Pimp Slapp'd," a track from "Paid tha Cost" that includes cameos by an L.A. gang leader who has since filed a lawsuit against Snoop for sampling his voice.

"I have no hate for Bloods, just one particular fake-ass Blood," says Snoop, referring to Knight. He claims Knight egged him on, plastering his face on the cover of an album titled "Dead Man Walking," even promising a car to the man who'd cut Snoop's hair. After the April shooting, a Web site for Death Row, now called Tha Row Records, featured Snoop, the sound of gunshots, and a whimpering dog.

"Snoop don't threaten me or nobody on my label," Knight told me at a charity Mother's Day brunch he throws annually in Beverly Hills. "I mean, we never see the guy. He don't come out, and if he do come out, the people don't feel him. They don't respect the simple fact of who he is, because every time he come out he gets shot at. And if he do go out, it's like a million police, or, for him to go to the restroom, 20 people gotta walk with him. That's not living."

At a magazine shoot in New York, Snoop insists on featuring a "Fuck Simon" T-shirt (Simon is a nickname for Suge). Uncle June Bugg, busy trying to chat up any woman at close range, doesn't seem to notice; Abbott fires off frantic two-ways; Snoop's bodyguards, slumped in chairs like exasperated parents, can only roll their eyes -- just as they did when Snoop blasted "Pimp Slapp'd" in his Vegas hotel room.

"Artists shouldn't get into feuds if they're just doing it for sales, because they should be able to deal with the repercussions," Knight declares, wiping a bead of sweat from his brow. "They shouldn't listen to the executives because while executives are at home, watching TV or playing golf somewhere, these guys are trying to hang out in clubs, and that's when the feud starts, and it's real life."

Knight puffs on his cigar. "So I think they should be careful what they say, or if they say it, they should mean it and deal with it -- and when you have to deal with it, stop calling the police. If you have a problem, be able to roll by yourself. You shouldn't have to be saying 'we, we, we' all the time. If you cut out all the extra fat, most people would stop talking their mouth so much."

At the magazine shoot, an onlooker attempts to explain the Suge-Snoop enmity. "Snoop's a Crip," she says, pronouncing the word with awe. It's the routine performed for a gangsta-curious public: Is he or isn't he?

"Snoop was a rapper. He wasn't into gangbanging -- it was nothing like that," says Snoop's first bodyguard, McKinley "Malik" Lee. "He sold weed, he went to jail a few times, but he wasn't some big gangster. Snoop was a character. He was comical, a ladies man, a player. He wasn't anything like the music. Matter of fact, I couldn't understand why he chose to take his music that way."

Growing up on 21st Street in Long Beach, Snoop sang in the church choir and listened to music he still loves: Al Green, the Dramatics, Curtis Mayfield. At Long Beach Polytechnic high school, recalls longtime friend Nate Dogg, "I'd beat on the desk and Snoop would freestyle." Snoop, Nate, and Warren G formed the rap group 213 and eventually got successful producer (and Warren's older stepbrother) Dr. Dre to give their demo a listen.

"Snoop was funny and he made me laugh, but the guys he hung out with -- I didn't like them at all. So I told him I wouldn't go out with him at first," Shante recalls. A month later, she says, Snoop was back at her door a changed man, no longer hanging around the Rolling 20 Crips. His music, though, was awash in Crip talk, which was enough to turn debut video shoots into anti-Snoop mini-riots, especially -- as was once reportedly the case -- when they were filmed in Blood neighborhoods and Snoop wore Crip-style blue.

"The people he grew up with knew the reality -- that he wasn't Cripping like that -- but others didn't," says Lee. "You reap what you sow. You speak it into existence." After Snoop's debut on "The Chronic" made him famous, Death Row installed him and Lee in small apartments that Knight owned in the working-class Palms district of L.A. It was an attempt to keep Snoop from harm's way -- and it failed. Here's the popular account of what happened in August 1993 at a park near that apartment: Gangsta rapper Snoop Dogg showed authentic Crip colors when he and his bodyguard feuded with a 20-year-old rival named Philip Woldemariam, who was killed. Snoop landed on the cover of major music magazines. Death Row happily surrendered to the marketing frenzy, recording a video for the eerily appropriate Snoop single "Murder was the Case." "Doggystyle" flew from record stores.

The account given by Paul Palladino, the private investigator who got Snoop and Lee acquitted, is far less glamorous. "It wasn't a gang dispute -- the case was much more complicated than that," he explains. While Snoop and Lee were inside Snoop's apartment, which was known to house the rap star, Woldemariam and friends -- drug dealers with a paranoid theory that Snoop would usurp their business -- threw gang signs at a coterie of Snoop's friends who were loitering in front of Snoop's building. Later that day, when Snoop was driving his SUV to the studio with Lee beside him, Woldemariam and crew flagged the car down, approached its passenger side, and pulled a gun; in self-defense, Lee fired and Woldemariam was killed. Ironically, Snoop's lyrics, which had created his gangsta identity, were cited at hearings as proof of this very identity.

"Everybody on the streets was saying it was gangster this and gangster that, but it had nothing to do with gangs," says Lee. "If that trial wouldn't have happened, though, Snoop's album wouldn't have dropped the way it did. 'Murder was the Case' was recorded two years before the shooting ever happened."

Lee claims that the April shooting was prompted by Snoop's presence in the very neighborhood of "the deceased," where Snoop still has enemies. "Of course there's still beef! A life was taken, and to people in the streets, Snoop Dogg did it. If there was peace made, it's one thing, but there was never any closure -- it was never spoken on righteously. Snoop needs to call a meeting, a press conference, and say that that murder wasn't about gangs, say to the family, 'Hey, we didn't even know who your son was.'"

But in Snoop's vision of the universe, he's moved passively along by a larger-than-life force. "I'm a child of God and I walk in the right way, so I'm not worried. If something is gonna happen, God's gonna make it happen," says Snoop, asked if he felt afraid in 1995, when he and his bodyguards fled from gunshots at a video shoot in New York -- or if he feels afraid now.

"When the [April] shooting happened," says Shante, "I got kinda down -- like 'How come we have to live like this?' It's like, he had a dream and he wanted to fulfill it and it's fulfilled -- so what do you do now? I just pray." She remembers the day after the shooting, when Corde came home from private school upset. "He said, 'Mom, why does everyone keep asking me if Dad's OK?'"

We're waiting on Snoop at a small house in the Valley, where he'll shoot a segment for one of his final Jimmy Kimmel appearances. Crew members are discussing last night's show, which featured Snoop and the rapper he toured with this summer, the enormously successful performer credited with the recent East-Coast rebirth of gangsta rap: 50 Cent. "Is Snoop a real gangster?" one staffer asks me. Before I can respond, another staffer interjects. "You know who's a real gangster? That 50 Cent." All nod in reverent silence.

Several bodyguards arrive at the house; others arrive later with Snoop, who's running on what Abbott calls "Snoop time." One bodyguard regales me with stories of his trip to Brazil, where Snoop was shooting the video for "Beautiful." The video has a different aesthetic from Snoop's previous video, which served up gangsta delights: blue bandannas, low-riders, and an abusive LAPD officer. The bandanna, however, was worn by a Snoop doll; the low-rider was an outrageous Snoop DeVille; and the officer a comic dwarf. If 50 Cent's aesthetic is "real," used as an un-ironic epithet even in a post-postmodern era ("50 is real, so he does real things," reads his Web site), Snoop's is so deliberately artificial it's camp.

Lil' Half Dead arrives with Snoop. He's fresh out of jail and says he sometimes has to drive around the block before entering his own home, because he'll always have enemies.

"No one, including Snoop, wants to live the kind of life it would take to truly be safe. He'd have to never bring old homies around, because it's usually the friends who end up starting all the drama," Palladino had told me, recalling a scenario early in Snoop's career when Snoop, arrested for firing road-rage shots at a police officer who took down his license plate number, was released upon discovery that Snoop's friend -- driving Snoop's car -- was the one who'd fired the shots. "I told Snoop, 'With friends like that, you don't need enemies.'"

Later that day, when I ask Snoop what he'd change about the music industry, he turns melancholy. "The untimely deaths," he says, stone-faced. One such death is that of Snoop's friend Tupac Shakur, a gangsta rapper who was one-part political poet and one-part gangsta posturing. This latter part earned him the enemies who were his tragic undoing. Unidentified gunmen murdered Tupac in Las Vegas in 1996, but he still sells records, containing songs recorded before his death; he still appears, saintly as ever, in nostalgia-ridden music videos. He's the embodiment of Robert Warshow's famous essay about the gangster archetype in American culture, which claims that because the genre must culminate in a fatal climax, one can only be a true gangster in art or in death.

"If you want to leave it all behind, you have to sever ties with the past, really," says Palladino. "Suge couldn't do it, and he still won't. How can you do that when you're under enormous pressure to stay true to the streets?"

Russell Simmons, chairman of Def Jam Records and one of hip-hop's most high-profile spokesmen, says it can be done. Recalling a recent vacation he took to St. Bart's with platinum rapper Jay-Z, Simmons is wistful. "Here's a kid from the projects on my boat, loving life. He doesn't want to be involved in shoot-ups. He's grown past that." Simmons claims that even today's most successful live gangster, 50 Cent, can also grow past it, and still maintain his fan base. "Hip-hop is defined by change," he insists.

Back in the Valley, Snoop is ready to be filmed. With his Long Beach buddies milling about, Snoop shoots a short skit in which he's having a garage sale, peddling bongs, hash brownies, and other such stoner paraphernalia. Actual neighbors line up to buy them. Then they watch in awe as Snoop, lost in a whirl of bodyguards, zips back to Hollywood.

Shares