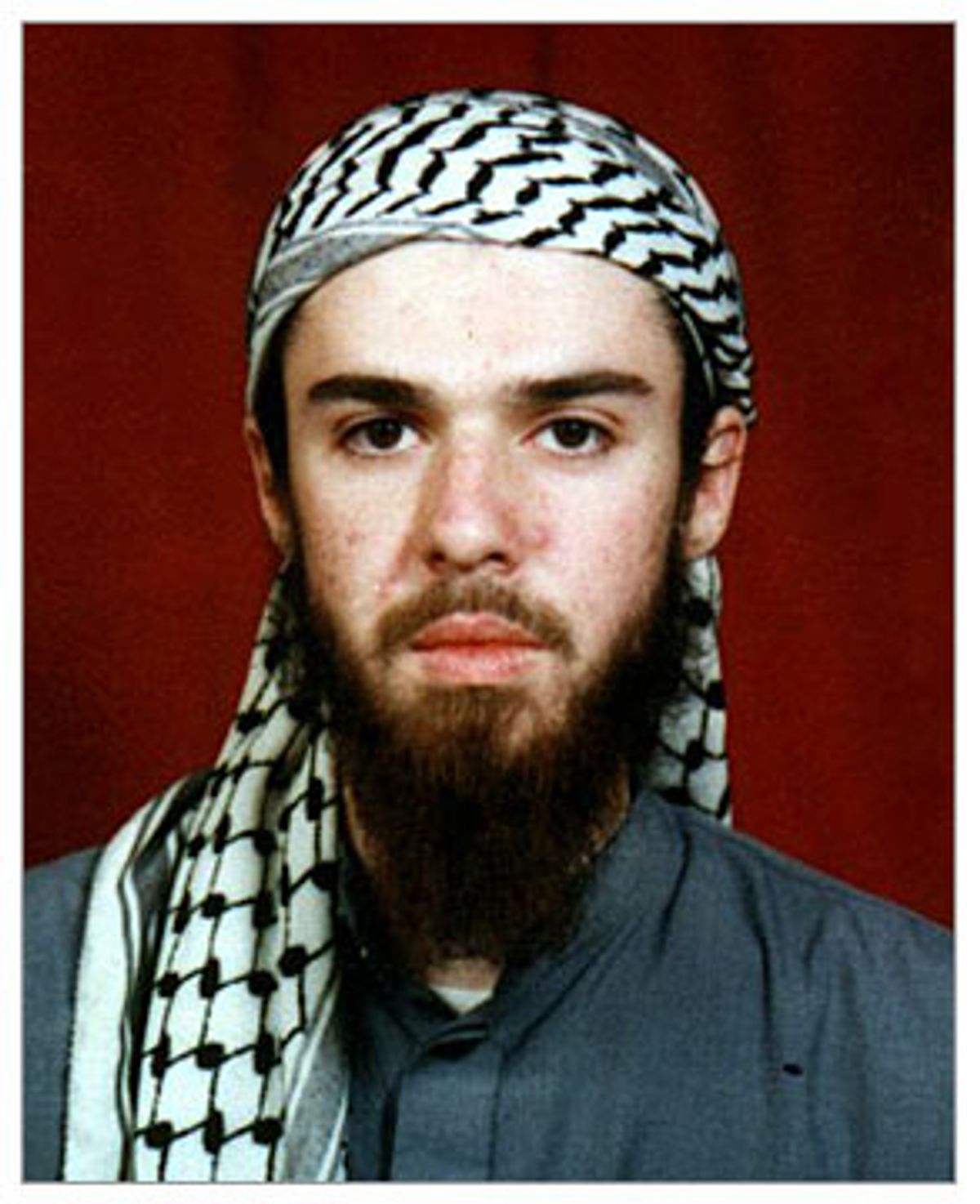

At 17, John Walker Lindh arrived in the Yemeni capital of Sana'a in July, 1998 looking to immerse himself in the study of Arabic and his newfound faith, Islam. He settled into a conservative Islamic university and pored over Arabic lessons and Muslim readings. And it wasn't long before he began parroting the conspiracy theories about the United States that flow through mosques and religious schools across the Middle East.

On August 7, car bombs exploded almost simultaneously outside Embassies in Nairobi, Kenya, and Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, killing more than 220 people, most of them poor Africans. It would prove a chilling hint of what would come to New York roughly three years later. The United States immediately blamed the strike on Osama bin Laden, and in 2001 a federal court in New York convicted four accused al-Qaida operatives of staging the attacks.

But on Sept. 23, 1998, Lindh wrote a telling note home in which he doubted the involvement of Islamic militants in the recent bombings of U.S. Embassies in East Africa. To Lindh, the bombings seemed "far more likely to have been carried out by the American government than by any Muslims." In a later e-mail, Lindh wrote his mother, half-jokingly, that she should move to England: "I really don't understand what you're [sic] big attachment to America is all about. What has America ever done for anybody?" In yet another e-mail, he expressed his view that the United States had sparked the Gulf War. Lindh believed that an American official had "heavily encouraged" Saddam Hussein to invade Kuwait.

Lindh studied in Yemen for nearly a year when his visa ran out and he returned to Marin County. Reluctantly, he stayed with his family for about nine months, but the sunny, privileged life Lindh had grown up knowing in the Bay Area left him uncomfortable spiritually and unsatisfied academically, and he returned to Yemen in the early part of 2000 and spent much of the year studying. That fall, his visa was expired again. Pakistani missionaries Lindh had met back in California had made the informal, unregulated religious schools there, the madrassas, sound appealing. Soon, he was on his way.

The September 2000 trip to Islamabad would prove the pivotal move for Lindh. His studies of -- and passion for -- Islam would deepen. He would make the remarkable transition from a dedicated student of the Koran to a jihadi traversing Afghanistan with a ragtag group of militants. And little more than a year later, he would find himself carrying arms for the Taliban in a conflict that ultimately set him against U.S. forces.

This key chapter, for the most part, began at a madrassa run by Mufti Mohammed Iltimas Khan, who served as the self-appointed headmaster at his tiny religious school in Bannu, a desert town not far from Pakistan's border with Afghanistan. Like most madrassas, Iltimas's is Spartan and remote. From a dusty alley, two dented metal doors painted blue open into the school, which at first glance appears still under construction. Inside, it's little better. Iltimas's study, where Lindh sometimes slept, is bare except for a corner table holding the madrassa's only phone, a locked book cupboard mounted on the wall and a set of shelves standing over the suitcase of personal items Lindh left behind.

Iltimas and I sat on the floor of the study in the spring of 2002 talking and drinking tea with buffalo milk as the sound of boys chanting Koranic verses hummed through walls thickened with layer over layer of white paint hopelessly grimed by desert dust. Occasionally one of the younger boys would peel into long, high wails above the others for a few verses, carrying the chorus of chants sharply into the mosque's courtyard.

Not long before, Lindh had been among them. From here, Lindh managed to study, but also remain in touch with his family and friends in San Francisco by sending email at the Internet clubs in Bannu. On Dec. 3, 2000, he dropped his mother a note making fun of the recently elected President George W. Bush, calling him "your new president." And, he added, "I'm glad he's not mine."

In later notes home, Lindh expressed an increasingly dimmer view of the United States and the West. On Feb. 8, 2001, he wrote to his mother saying, "I don't really want to see America again."

Iltimas's madrassa houses roughly 40 boys aged 10 to 17 whose core studying -- which begins well before dawn and went to sunset -- revolves around memorization of the Koran. Lindh would sit rigid during his lessons, moving only his mouth as he recited. Iltimas urged Lindh to loosen up, and he did, somewhat, occasionally rocking stiffly in tiny sways that appeared hardly noticeable alongside the near gymnastic readings of some of his schoolmates.

As the only foreign student, Lindh took on a celebrity status of sorts, spending much more time with Iltimas than any of the other pupils.

"He was our guest student," Iltimas said of Lindh, whom he remembers fondly. "I used to ask questions about America, what type of civilization Americans have. I was far away from America, and he was near to us and near to them."

"One day he told me about his parents separation, I asked him, do they live together? After that he explained." Presumably, Lindh explained his parents' divorce, and that his father had announced he was gay. But Iltimas would only say that what Lindh told him was strictly "a secret for me."

Lindh's mother urged him to come home for a visit. But Lindh wrote on March 1, 2001, that he was "busy in my studies and I have no intention of interrupting them for any reason in the near future. ... I wasted about 9 months in America in which I achieved nothing and forgot much of what I had learned while in Yemen."

As he seemed to be quickly advancing in his studies, Lindh began to have vague ideas for future plans. He expressed his ultimate hope to become an Islamic teacher in America after furthering his education in Pakistan. And he talked of how he hoped to enjoy female companionship.

"He asked me the second or the third night if I were alone here," Iltimas recalled laughingly, baring teeth stained by countless cups of tea and squirming with an adolescent's giddy embarrassment at talk of girls. "I told him yes, I am unmarried. I asked him, Suleyman, how many marriages will you have? He told me four!" Four wives is the maximum number allowed for Muslims, Iltimas explains.

During one of their many hours of conversation, Lindh also told Iltimas how, after converting to Islam he began to feel uncomfortable living in the United States and became naturally drawn to Islamic countries, where his adopted faith played a part in everyday society. Lindh told Iltimas that he felt as though he could neither explore his newfound religion deeply nor live by the commands of Islamic scripture properly in his native country, where he saw many societal ills.

"He was fed up with American society," Iltimas said. "He was searching for a place where people follow and obey all the commands of Allah. America was not suitable for this."

Lindh also voiced his disenchantment with certain Islamic societies.

"He didn't like the present setup of Muslim governments," Iltimas said. "He used to say Muslim governments were in the hands of the West and America. He wanted an Islam like it was in its earliest days, free of influence by America and other outside powers."

Which is what appealed to Lindh about the Taliban, and Afghanistan. Iltimas smiled as he remembered the Radio Shariat broadcasts he would translate for Lindh. Before the Taliban lost power late in 2001, Radio Shariat broadcast readings of the Taliban's interpretation of Islamic law, which included decrees outlawing, among other things, all forms of art, which the Taliban saw as idolatry. The Taliban ideologues viewed virtually every element of human behavior as subject to stringent Islamic laws, which they twisted into perversions religiously unrecognizable to Muslims outside the radical school of fundamentalism taught in scores of madrassas by the likes of Iltimas.

"They were true Muslims," Iltimas said wistfully of the Taliban, a movement whose ranks had been flush from the earliest days beginning in 1994 with vigilante students educated in Pakistani madrassas. He said those who questioned the Taliban's brand of Islamic governance, the harshest ever seen in the history of Islam, were either misguided Muslims or Western demagogues bent on subverting Afghanistan and the wider Islamic world -- an argument the Taliban itself sounded throughout its rule.

Iltimas said Lindh's curiosity about Afghanistan initially seemed like a passing interest. But it grew. Soon, Lindh became convinced that the Taliban's Afghanistan embodied Islamic society in its purest form, a modern representation of the era of the prophet that began on the Arabian Peninsula in 610 A.D. with Mohammad's revelations near Mecca. The Taliban itself claimed they were shaping a society as such -- a pure Islamic state to lead the rest of the Muslim world, which they saw as adrift in Western corruption. Lindh began to act out some of the Taliban's creeds, showing scorn for art that was legal in Pakistan but banned just across the border. He scratched off pictures on the pads he used to jot down notes about Islamic histories, Arabic translations or Pashto vocabulary. One notebook Lindh left behind with Iltimas had an image of a galloping herd of horses on its cover. Lindh had blackened out the faces of the horses with a marker and tore at the bodies with deep, looping scratches of a pen.

An entry in his notebook also showed he grew interested in the battles between the Muslim Pakistanis and Indian Hindus in Kashmir. At the top of the page, Lindh wrote "Kashmir" in block letters, numbering seven points below, each one a war statistic he had taken from Islamic fundamentalist literature widely available in Pakistan. By Lindh's count, in the years spanning 1991 to 1999 some "60,000 Kashmiris have been killed" with another "26,000 wounded." He was convinced there were "461 school children burned alive" in the same period and that "700 women between ages of 7 and 70 have been raped." Still more, Lindh cited "39,000 disabled for life" and another "97,000 missing" with "47,000 forced from their homes."

The figures Lindh read about Kashmir were just some of the widely printed stories that appear daily in Pakistan's press, which has many English newspapers of dubious veracity that readily air propaganda about the issue. All the articles telling of tragedies in Kashmir, as well as the things Lindh heard word of mouth from Pakistanis, began to weigh more heavily on his mind.

Kashmir was just a day's drive. The idea of Muslims suffering so close roused Lindh, who began to wonder aloud why more Muslims were not coming to the aid of the Kashmiris, a religious duty clearly spelled out in the teachings of his favorite Islamic writer and scholar, slain Muslim holy warrior Shaykh Abdullah Azzam. In Azzam's time, Afghanistan had offered the most valiant cause for jihad, and indeed thousands of Muslims, including Americans, answered the call. Uncounted scores of American jihadis traveled to Afghanistan to fight against the Soviet occupation in the 1980s, a war effort financially backed by the Reagan administration.

The trend continued through the 1990s, though Afghanistan became but one of several other destinations for jihadis. Figures are sketchy, since U.S. authorities do not track the overseas travels of American citizens. But terrorism experts at the Federal Bureau of Investigation have estimated that up to 2,000 Muslim Americans left the United States during the 1990s to fight in places like Bosnia, Chechnya, Afghanistan and Kashmir. In Pakistan, authorities put the number of Americans jihadis who are believed to have trained in either Pakistan or Afghanistan since 1989 at around 400.

Followers of Azzam's brand of radically conservative Islam believed armed jihad, fighting in defense of their perceived oppression of Muslim lands and people, to be the requisite obligation of any able-bodied Muslim. In conversations with Lindh, Iltimas agreed in principle with Azzam's teachings, that Muslims were obligated to go on jihad if able to the nearest Muslims in need. Lindh began to wonder, then, what everyone was doing sitting around in Bannu. Why had Iltimas not gone to aid the Muslims in Kashmir?

"I'm not a warrior, I'm a teacher," Iltimas said.

Eventually, Lindh told Iltimas that he wanted to take a leave from his studies and escape, he claimed, to the North and its cooler climes to avoid Bannu's summer heat. Iltimas discussed the idea with Khizar Hayat, an Islamic missionary Lindh had met in San Francisco who had become Lindh's best friend in Pakistan. The mufti agreed to let Lindh go in May on a trip with Hayat. In what looks like Lindh's last e-mail home, he wrote to his mother in April 27, 2001, that he was going to "some cold mountainous region."

Lindh hardly packed anything. He took only a backpack and sleeping bag with him the day he left, leaving a full suitcase and his burgeoning library of books on Islam for safekeeping. Lindh didn't say when he'd be back.

"You're leaving but your things are still here, when will you return?" Iltimas recalled saying to Lindh in the doorway of the study as they said goodbye. Lindh shrugged and smiled but did not answer. He thought at the time that he might be gone for a couple of months before coming back to Bannu to pick up his things before returning to California to visit his family. He thought he would probably be back in the United States by Christmas 2001.

It was the last time Iltimas would speak to Lindh.

Lindh and Hayat traveled from Bannu to Peshawar, where they stayed for a few days with Hayat's uncle before Lindh left on his own, with little explanation, according to Hayat. Lindh had left behind a sleeping bag and a few other belongings, winnowing his possessions further still. Hayat said he returned to Bannu angry with Lindh.

"I showed him all of Pakistan," Hayat said. "When he left us, I left him."

Iltimas was also upset about Lindh's disappearance, especially after hearing from Lindh's mother. Shortly after Lindh left, a letter from Marilyn Walker arrived at Iltimas's madrassa. Postmarked July 2, 2001, the envelope was addressed to "Suleyman Lindh/Suleyman al Faris" care of Iltimas. Since Lindh was gone, Iltimas opened the note, which his mother began with "Dear Suleyman" and went on to beg him to call home "anytime of day until you reach me. Tuesdays and Thursdays after 2 PM (Pacific Standard Time) and weekends are best. Or, write and give me a way to reach you. I'll be leaving for the Sundance July 28 and should be back August 13. I hope that we hear from you before then. I really need to hear your voice, John! So, please call 'collect' and tell me what's up."

Iltimas put the letter aside, thinking he would save it for Lindh whenever he returned. Nine days later another letter from Marilyn Walker arrived, this one addressed to Iltimas himself. Lindh's mother told Iltimas that she had "lost touch with my son, Suleyman Lindh (Suleyman al Faris). The last I heard from him (via e-mail) was April 26th. He said that he might be moving into the mountains for a cooler climate during the summer months. Would you know where he is and how I may reach him or could you get a message to him to call home 'collect' or write?"

Lindh's mother included her address and phone number in the note, as well as a copy of the missive in Urdu. Iltimas saw Hayat in the Bannu bazaar shortly thereafter and told him about the letters. Hayat told Iltimas that he had heard in the bazaar that Lindh had indeed made it north. Iltimas relayed this in a lengthy reply to Marilyn Walker dated July 27, 2001. Iltimas told Lindh's mother how he got her letter a "few days back but unfortunately due to various reasons I could not reply in time. Sorry for the delay.

"John Lindh Lindh/ Suleyman Faris is no doubt your son, but rest assured that he is my student and also my younger brother. He is a very sweet, honest, Godfearing and a very decent human being ... . rest assured Madam, whenever he contacts me, I will definitely convey your feelings to him." Iltimas also wrote: "I will also, in my own way, start inquiries to know about his location and health. He is like a younger brother to me and will spare no efforts to know about his welfare."

He did not tell her, however, what he strongly suspected: That her son had gone off to war, to fight with Muslim jihadis in Kashmir.

Lindh's mother still had heard nothing from her son when she wrote Iltimas once more in a letter dated August 19, 2001, in which she thanked Iltimas "so much for responding to the letter regarding my son, Suleyman. I cannot tell you how much it means to me to know that he is cared for by so many in a land so far from home. I appreciate your concern for his well being and your offer to seek information about his whereabouts. We miss him very much. It isn't like him to have gone so long without making contact with us. If you are able to make contact with Suleyman and he is able to phone home, please tell him to do so 'collect.'" She signed off by giving her phone numbers and telling Iltimas to call her "any time with any news you may have about him."

But Iltimas made little effort to find Lindh, despite his promise. Iltimas asked people at Bannu madrassas and mosques who had recently traveled if they had seen Lindh, but no one had. He made plans to go to Mansehra himself, but put them off initially to attend a month-long religious conference, and then canceled them altogether after Sept. 11. In any case, the mufti thought the matter rested with Hayat.

For his part, Hayat painted the picture of his relationship with Lindh as one of an Islamic missionary guiding a hopeful Muslim convert toward a similar path of peaceful proselytizing in the United States. To Hayat, Lindh was a lost missionary, though gone to a worthy alternative cause. Hayat denied playing any role turning Lindh toward jihad.

At the time, Hayat's story seemed plausible, and he struck me as sincere, if laconic and temperamental. Except in one regard. He claimed to have no idea who, if not him and Iltimas, might have introduced Lindh to members of Harkat ul Mujaheddin, the Pakistani militant group that would give Lindh his first arms training. Hayat said Lindh met many people in Bannu, people Hayat didn't know.

"He was meeting so many people, who knows who he was talking to?" Hayat said, speaking to me one afternoon as I sat with him at his father's store in the bazaar, taking the same seat where Lindh would often studiously read his Koran.

Hayat's complete unwillingness to name anyone among the people he saw Lindh talking with in the bazaar and at the Bannu mosques left me thinking that he either helped arrange Lindh's initial enlistment with Harkat ul Mujaheddin or knew exactly who did. But Hayat remained unwavering in his account whenever I confronted him with doubts, saying I should take up any unanswered questions with the one person who knew all, Lindh himself.

"He's alive, you can ask him," Hayat said.

Like Hayat, Iltimas washed his hands completely of having anything to do with helping Lindh go on jihad. But he stopped well short of condemning Lindh for doing it.

For Iltimas and Hayat, Lindh's two closest friends in Pakistan, there was no question. The Taliban and their Muslim brethren in Pakistan and India were righteous before God, and their missions were at least as worthy as any other Islamic undertaking -- if not more so.

Part II: A meeting with bin Laden, and Lindh's capture after a violent revolt

Shares