John Walker Lindh reported to Osama bin Laden's al Farooq training camp outside Kandahar in June 2001 with about 20 other volunteers, mostly from Saudi Arabia. The desert base was similar to the mountain camp in northern Pakistan where Lindh received his first arms training with Kashmiri militants weeks earlier. But these grounds were home to Arabs, rather than Afghans or Pakistanis, and the men who ran al Farooq had even darker ambitions than training and arming a guerrilla force.

Living in a tent, Lindh joined about 100 Arab volunteers at the camp, which sat on a hidden canyon floor in a chain of low mountains arching across the desert plain surrounding Kandahar. Instructors woke recruits early and ran them through a daily regimen of running, hiking and arms training, broken up by prayers. The trainees had target practice and learned how to handle grenades and Molotov cocktails. They went on camping excursions and learned battlefield tactics such as different types of combat crawls, surveillance methods, camouflage techniques, signs and signals, navigation of rugged terrain and how to carry weapons properly.

The trainees gathered together in the evenings at the camp mosque. But instead of accountability sessions, al Farooq offered guest speakers every night. Among the lecturers who addressed the group was Osama bin Laden, who showed up at the camp a handful of times toward the end of Lindh's course.

The evening lectures had always been a chance for Lindh and other recruits, who sagged at the end of a day's training, to nod off. Sitting through a bin Laden lecture required a special kind of endurance. Bin Laden, apparently ill, spoke softly and slowly as he sipped water during his talks, which covered topics ranging from local problems to global politics. Lindh dozed through at least one of bin Laden's lectures, and found the others unmemorable, despite bin Laden's obvious stature in the camp.

Lindh also had heard rumors that bin Laden masterminded the embassy attacks in East Africa, and he knew that the wealthy Saudi had worked with Azzam and supported jihadi causes. But he had also heard that bin Laden thought jihadi struggles like Chechnya and Bosnia were a lost cause, leaving Lindh uncertain of what to make of him. Also, Lindh disdained how some in the camp looked with reverence to bin Laden, who was always accompanied by an unusually large entourage. Lindh felt jihad was not a celebrity cause, and that bin Laden's apparent stardom did not mesh with the egalitarian ideals of Islam.

Each time after bin Laden spoke, recruits who wanted to meet him would line up for a handshake. Lindh passed on the first evening, as did some of the other trainees, and went back to his tent to sleep. On one of bin Laden's other visits, however, recruits were told at the end of bin Laden's talk that they could either meet the famed Saudi exile, or do camp chores after the mosque session. Some of the camp instructors had told Lindh beforehand that anyone who wanted to meet bin Laden had to be sincere about jihad, since many in the camp seemed ready to drop out. Lindh was indeed serious about jihad -- and wanted to get out of work detail -- so he joined four other trainees, with whom bin Laden spent about five minutes, thanking each for volunteering.

The meeting seemed insignificant to Lindh at the time, an excuse to avoid unpleasant camp duty. He didn't know the United States already wanted the terrorist leader for mass murder, or that in those very days bin Laden was orchestrating the death of thousands more in New York. He walked away thinking little of the encounter, eager only to be done with training so he could finally go on duty with the Taliban.

But toward the end of the course, an al Farooq instructor approached Lindh and others to ask if anyone would be interested in taking up jihad in either Israel or the United States.

Lindh and his comrades thought the offer was a trick question, an effort by the Arabs who ran the camp to ferret out spies rumored to be among them. But the recruitment was likely for real.

One of the ranking al Farooq trainers, Abu Mohammad al-Misri, an Egyptian also known as "Shaleh," had been named in a federal indictment for his alleged participation in the 1998 embassy bombings. Again, Lindh knew nothing of him. Regardless, he turned down the offer to leave Afghanistan, saying again that he had come to help the Taliban. Lindh left the camp in June or July at the end of his training, and soon joined a group of about 30 other Ansar volunteers headed north to fight Northern Alliance forces, who were then clinging to a tiny corner of Afghanistan in a losing war.

Lindh arrived on the front lines in the war's eleventh hour. His group flew in on one of the last troop lifts from Kabul to Konduz on about Sept. 6, 2001. In Konduz, Lindh was given a Kalashnikov and two grenades, a vest with pockets for his ammunition, and some warmer clothes since winter was already coming in the mountains. A Taliban commander told Lindh and the others in the group that they were officially members of the Afghan army, even though there was not an Afghan among them. With that, Lindh saw himself as a sworn servant to the Taliban's Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan, a soldier not a terrorist -- a distinction that would come to mean little, if anything, in the eyes of most Americans.

Lindh's unit was then sent toward the front lines in Takhar, where the group was ordered to take up defensive positions on two hills opposite Northern Alliance forces. Lindh was told his group would make no attacks; their mission was simply to hold the hills, essentially guard duty at a position that weathered only the occasional volley of Northern Alliance mortar fire. His long-anticipated jihad consisted of touring a remote corner of the front line where the Northern Alliance forces were so far away that the Taliban rarely, if ever, saw them. Lindh never managed to squeeze off a shot across the front lines, and his unit suffered no casualties while protecting the lonely hills. He mostly read and eyed the empty landscape, rotating with others in two-week shifts in and out of foxholes.

Word of what happened on Sept. 11 spread by word of mouth from others in his unit who listened to radio broadcasts. With no access to a radio himself, much less a television or newspaper, he was unsure what to think of the attacks and the speculation that bin Laden was behind them. In any case, Lindh saw bin Laden and any conflict he had with America as separate from the Taliban's fight against the Northern Alliance. He was tragically wrong in many ways.

Eventually Lindh and others began to suspect that bin Laden was indeed behind the attacks, a troubling revelation for some on the remote front. The moral, ethical and religious reasoning that had drawn Lindh and many of his jihadi comrades to fight in trenches against fellow Islamic believers in Afghanistan did not call for the attacks like those unleashed on Sept. 11. And whatever misconceptions Lindh had about bin Laden, one thing was clear: the Taliban supported him. Many of the foreign fighters in the trenches alongside Lindh began to question the Taliban and its support of bin Laden as sketchy details about the thousands of civilian casualties reached them in their lonely post.

Some considered defecting, looking for ways to flee Takhar. But U.S. airstrikes, which had begun on Oct. 7, had frozen all transportation to and from the area. Slipping away on foot seemed out of the question. A walk back to the nearest town of any size, Konduz, would take more than two days over frigid steppe supposedly roamed by bandits. There seemed to be no way out, so Lindh never really considered abandoning his position. But eventually he and his colleagues were forced to, as the airstrikes were breaking up Taliban positions elsewhere along the front, and Lindh's unit was ordered to fall back.

By mid-November, they moved from their positions and the entire front line folded; all the Taliban in the area broke into a full retreat toward Konduz. By the time they reached it, the town was controlled by the Northern Alliance and the Taliban soon accepted defeat -- at least officially -- and entered into surrender talks.

Around November 24, Lindh and several hundred other foreign fighters were ordered by Afghan Taliban commanders to turn themselves over to the Northern Alliance soon after they arrived in Konduz. Lindh and others were told by a Taliban commander that they would be let go after being disarmed. Whether the Taliban commander believed that or not, Northern Alliance Gen. Rashid Dostum had no plans to free any of the surrendering foreigners. Instead, Dostum's men trucked them to his fortress on the outskirts of Mazar-e-Sharif called Qala-i-Jangi. There Northern Alliance troops crowded Lindh and roughly 400 other captives into a basement for overnight keeping ahead of interrogations. The packed cellar was a din of fighters speaking in no fewer than half a dozen languages echoing off the cement walls. Lindh crouched on the dirt floor near a corner used as a toilet because there was no room to lie down anywhere else.

Lindh's brief time as an armed Taliban fighter was over. But he would not escape the brutalities of war.

As the sun rose on the chilly morning of November 25, Northern Alliance guards descended to the basement to begin bringing up the prisoners for interrogation. At about 10 a.m., after some 200 prisoners had left the basement without incident, Lindh too mounted the double plank of metal stairs leading from the cellar. At one point, as Lindh sat motionless, one of Dostum's guards struck him in the head, leaving him dazed as he watched two men who appeared to be Americans question prisoners one by one.

Lindh thought the two Americans were somehow under the command of Dostum, renowned among Taliban for his brutality, because Afghan guards aided them and took orders from them. It seemed to Lindh that the two Americans must have seen the guards beating the prisoners randomly, but neither appeared concerned. Lindh began to fear that if identified as an American he would be separated from the group and kept behind in Dostum's custody for further questioning. Lindh dreaded the idea of remaining in Qala-i-Jangi, where he expected to be tortured and killed by Dostum's men.

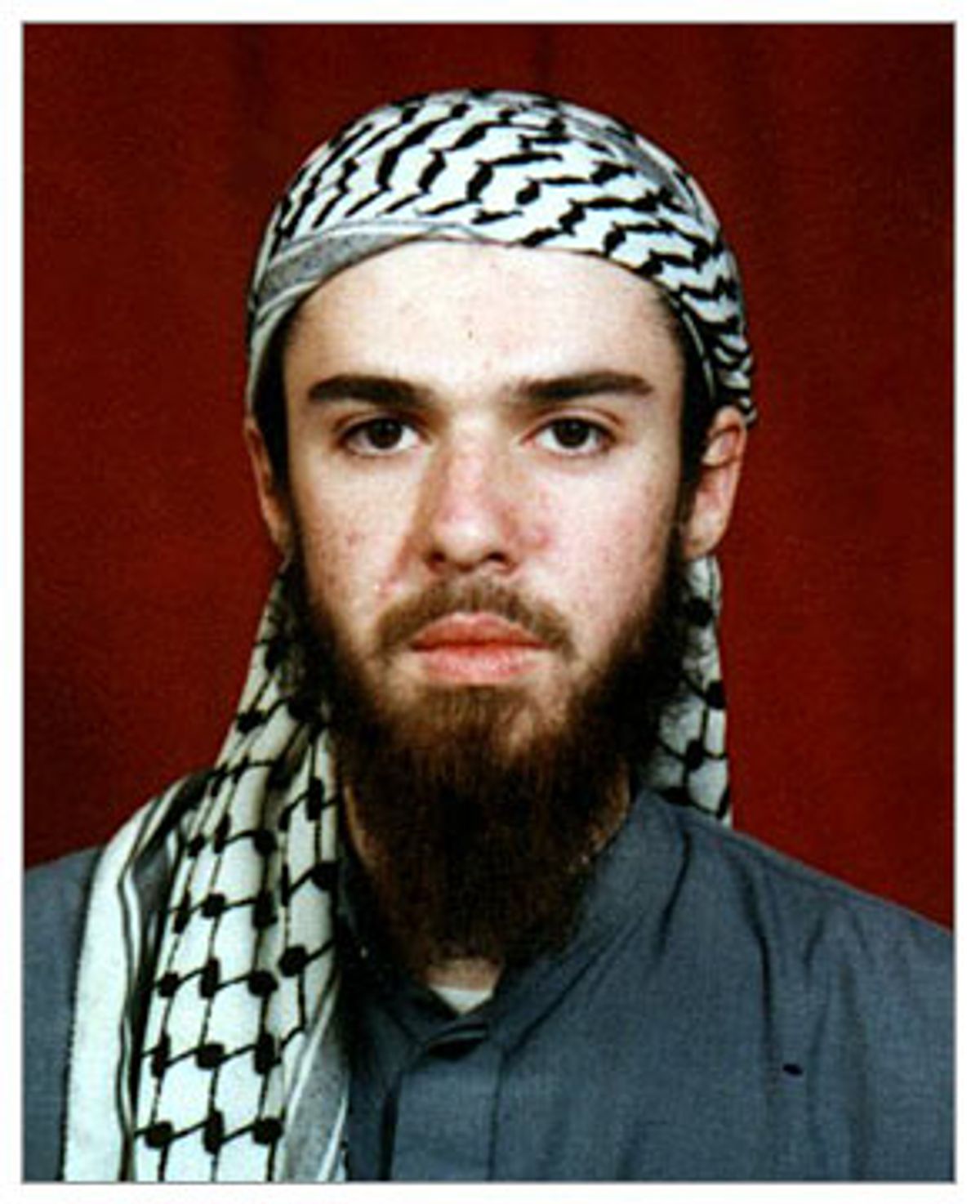

The Americans Lindh saw were CIA operatives Mike Spann and Dave Tyson. During the early interrogations, an Iraqi prisoner had told Spann that there was an Irishman among the prisoners. Spann noticed Lindh in the group and was told the disheveled fighter, whose skin was lighter than most, had been overheard speaking English. Lindh also drew the attention of an Afghan camera man, who began videotaping Lindh, providing an eerie record of one of the most compelling moments of the war -- two Americans face to face in a remote corner of Afghanistan, each there for reasons of conviction, yet on opposite sides of battle lines.

"Hey, you, right here with your head down," Spann called to Lindh as he sat limply among the other prisoners.

"Look at me; I know you speak English," Spann said, eyeing Lindh as he sat unresponsive. "Look at me. Where did you get the British military sweater?"

Northern Alliance guards hauled Lindh to his feet and shoved him over to a blanket spread over the dirt, where he kneeled and sagged his head, letting his long brown hair fall over his face.

"Where are you from?" Spann said. "You believe in what you're doing here that much, you're willing to be killed here? How were you recruited to come here? Who brought you here? Hey!"

Spann snapped twice in the prisoner's face but still got no response.

Spann matched Lindh's silence for a moment, looking him over in a long pause as a distant autumn sun rose and warmed the chill morning air. Square-jawed with a neatly trimmed mustache, Spann was built like a brick house. The brawn in his chest and shoulders showed through even the heavy fleece he wore with his jeans. Lindh by this point looked like a wasted waif.

Lindh glowered and hunched angrily until a nearby Afghan guard reached over, pulled his hair back and held his head up for Spann's digital camera. The expression of defiance and angered humiliation Lindh wore Spann had undoubtedly seen on the others he had already questioned.

"You got to talk to me," Spann said. "All I want to do is talk to you and find out what your story is. I know you speak English."

Lindh said nothing, and Spann clearly displayed frustration when Tyson walked over.

"He won't talk to me," Spann said. "Well, he's a Muslim, you know," Tyson said, lowering his voice for a moment to talk quietly with Spann before going on to speak loudly enough so Lindh was sure to hear.

"The problem is he needs to decide if he wants to live or die, and die here," Tyson said. "We're just going to leave him, and he's going to fucking sit in prison the rest of his fucking short life. It's his decision, man. We can only help the guys who want to talk to us. We can only get the Red Cross to help so many guys. If they don't talk to us, we can't ..."

Spann suddenly turned to address Lindh. "Do you know the people here you're working with are terrorists, and killed other Muslims?" he said. "There were several hundred Muslims killed in the bombing in New York City. Is that what the Koran teaches? I don't think so. Are you going to talk to us?"

"That's all right, man," Tyson said. "Gotta give him a chance, he got his chance."

Indeed, Lindh had his chance, but he wasn't taking it with Americans. Foolishly, he still hoped that somehow the group would be freed, and allowed to leave the fortress peacefully after the interrogations.

Spann still had no idea Lindh was an American as a guard pulled Lindh to his feet and shoved him to an area with the other previously interrogated prisoners. And he didn't live long enough to find out what the rest of the world would soon know.

About half an hour later, as alliance guards called into the cellar for another prisoner, as many as half a dozen, mostly Uzbeks, suddenly rounded the steps, tossing grenades, yelling, "Allah u Akbar!" The guards fired into the crush of prisoners charging up the stairs but were soon overpowered as more men leapt up behind them and fought toward the outside door.

It was the beginning of an uprising.

Seated by the side of the building, Lindh heard the sound of shots and screams and rose to his feet as some of the prisoners around him began shouting and untying each other. He turned to run but was shot in the leg as alliance fighters standing on the roof of the building fired Kalashnikovs down into the yard, spraying the scattering prisoners. Elsewhere in the yard Spann had gone down under a crush of prisoners who rushed him, becoming the first U.S. casualty in America's war against the Taliban.

As the gunfire of the revolt quickened, Lindh lay bleeding, motionless where he fell, watching the bloody scene unfold. He and another wounded prisoner lay in the yard playing dead for the duration of the 14-hour shootout.

At nightfall, as the battle wore on, Lindh's Taliban comrades dragged him back into the basement, where he remained for nearly a week with holdouts from the revolt until the Northern Alliance finally forced them to surrender. When Lindh emerged from the basement again he was among 86 of the surviving 400 Taliban, whom the Northern Alliance brought to Dostum's personal home outside Mazar-e-Sharif.

- - - - - - - - - - - -

Twelve Green Berets, two Air Force bomb guiders and three CIA operatives, including Spann, had been traveling with Dostum since October, when they were assigned to help his faction of the Northern Alliance as part of the U.S. campaign in Afghanistan. Author Robert Young Pelton had joined Dostum's entourage during the uprising at Qala-i-Jangi, having arranged to take a small CNN crew with him on a monthlong assignment profiling the warlord for National Geographic Adventure magazine. Pelton had quickly become friends with many of the Green Berets, who recognized him from his books and television show.

Pelton and the Green Berets were watching television at Dostum's house the night of Dec. 1 when they heard a loud bang at the gates. The group went out to find Dostum's men unloading dozens of wounded from two trucks and lining the prisoners up in a gloom of swirling dust aglow with headlights. Earlier Pelton had asked Dostum's men to show him any prisoners taken from the basement so he could interview them. Dostum's men had obliged, bringing all 86 men from the basement to Pelton. Like others, Pelton had heard that perhaps a handful of men remained in the basement and was stunned to see so many survivors. Many of the prisoners were barely alive and wailed in pain as Dostum's men pulled them off the trucks while Pelton and the Green Berets looked on.

Pelton took some pictures while the Green Berets urged him to be careful and stay back. Initially Pelton didn't notice Lindh, and after several minutes of photographing the group, he urged Dostum's men to take them to the hospital.

At the hospital, Lindh was unable to stand and had to be carried by stretcher into the makeshift emergency ward, where he was placed on the floor with the other wounded from the basement, all of them near death. One of Dostum's personal cameramen had gone to the hospital and was taping the scene, turning his camera on the wounded one by one as the doctors asked each individual his name and nationality. Lindh wearily said he was American when the doctor came to him. Stunned, the cameraman ran from the ward back to the palace to tell Pelton.

Several Green Berets, including a medic, went with Pelton to the hospital, where Pelton interviewed Lindh for CNN, made sure the boy got badly needed medical care and offered to help him get in touch with his family.

"And did you enjoy the jihad?" Pelton asked Lindh. "I mean, was it a good cause for you?"

"Definitely," Lindh said.

After the interview the Green Berets took Lindh back to Dostum's house, where Lindh slept as Pelton's interview began to air on CNN Dec. 2. John Walker Lindh became a household name.

The Green Berets woke Lindh up early the next morning, bound his arms and blindfolded him. A three-car convoy set out from Dostum's house back to Mazar-e-Sharif, where Lindh was taken to the main coalition base in the area, an unused high school where military officials interrogated him over the course of several days. He talked and talked, urged on by his interrogators who told him that anything he knew might be able to save American lives.

Some of the soldiers who had to deal with Lindh grew disgusted after learning where he had been and what he had done. His guards in particular began to show open disdain, along with traces of fear. They frequently called him "shit bag" and "terrorist," as well as "shithead" -- the nickname that stuck.

At some point during those initial days of questioning, which lasted from Dec. 2 to Dec. 7, it struck Lindh that he might need a lawyer, and he asked his military keepers when he could seek an attorney. But the officers on hand neither had an answer for him nor seemed overly concerned with Lindh's request. They wanted battlefield information that might be of use to the ongoing conflict, not evidence of criminal wrongdoing. Orders had come from the Pentagon that Lindh was to be questioned about military, not criminal, matters. The FBI, U.S. officials decided, would ask any questions about possible law violations later.

On Dec. 7, military officials planned to fly Lindh to Camp Rhino, the main U.S. base in Afghanistan outside Kandahar. In preparation for the journey, U.S. troops bound and blindfolded Lindh, tying his hands tightly together with plastic cuffs. On Lindh's blindfold U.S. troops scrawled "shithead," and they taunted him as they took turns posing for snapshots next to their infamous prisoner.

One soldier told Lindh he was "going to hang" for his crimes and that upon his death the soldier would sell the souvenir "shithead" blindfold snapshots and give the money to a Christian charity. Another soldier told Lindh that he'd like to shoot him then and there. But instead, they marched him from his quarters, shoved him into the back of a van, and drove him to the Mazar-e-Sharif airport. There, they hustled Lindh onto a cargo plane.

Onboard, the plastic cuffs dug into Lindh's wrists, sending sharp pains through his arms. At some point during the flight Lindh began to beg the unseen troops around him to loosen the ties, screaming to be heard over the engine noise of the plane. But Lindh's guards simply told him the cuffs weren't meant for comfort. And then Lindh began to grow scared.

"Please don't kill me," he pleaded, speaking blindly to the soldiers around him.

"Shut up," someone near said.

It was night when the plane touched down at Camp Rhino, about 70 miles south of Kandahar. Lindh's guards initially put him face down on a stretcher, and he thought for a moment that he might be en route to his execution. The frigid winter air in the high desert darkness swept cold over Lindh as the Marines unloaded him from the plane.

"Please don't kill me," Lindh begged again.

"Shut the fuck up," one of the Marines nearby said.

Lindh's guards cut off the clothes he had been given in Mazar-e-Sharif, leaving him naked as they bound him to a stretcher with duct tape wrapped tightly around his chest, upper arms and ankles. Troops at Camp Rhino took more pictures of Lindh as he lay naked, taped to the stretcher, blindfolded in pain and fear. Then they placed him in yet another metal shipping container, where Marines questioned him for roughly 45 minutes before leaving him to lay shivering alone, crying. After some time, guards returned to wrap him in blankets, but left him bound so tightly that his forearms were pinned together in front of him, pointing down. The Marines kept him like that for two days, inside his windowless compartment, unknowing of when day and night passed. Small holes in the sides of the container provided the only source of air and light, through which troops yelled swearing insults and loudly discussed how they planned to spit in his food. When Lindh needed to urinate, his guards simply propped up his stretcher vertically, leaving him bound.

Lindh began Dec. 9 cold and hungry. He was given a meal with pork, which he refused to eat. His guards then gave him another meal and a new blanket. Shortly thereafter, Marine guards entered Lindh's container, tore off the duct tape, dressed him in a hospital gown and shackles and then carried him on his stretcher, still blindfolded, to a nearby tent. When guards removed the blindfold, Lindh sat facing Federal Bureau of Investigation Agent Christopher Reimann, who introduced himself and then immediately read Lindh his rights. When Reimann came to the point related to one's right to an attorney, he said, "Of course, there are no lawyers here."

Reimann questioned Lindh in three lengthy interrogation sessions over the course of two days after Lindh waived his Miranda rights both verbally and in writing. After questioning, Lindh was allowed to wear clothes again and was no longer taped to furniture inside his box, but Reimann's interrogations were shaping up as something bad for Lindh nonetheless.

On Dec. 14, a helicopter flew Lindh from Camp Rhino to the USS Peleliu, a warship afloat about 15 miles off the coast of Pakistan, where he would remain for 17 days before being transferred to the USS Bataan. In mid-January of 2002, as Lindh sat jailed in the belly of a U.S. warship at sea, the government filed an affidavit and obtained an arrest warrant for him, clearing the way for a civilian trial in the United States. Last October, he was sentenced to 20 years in federal prison, after pleading guilty to aiding the Taliban and carrying explosives. With time off for good behavior, he will still need to serve 17 years.

Shares