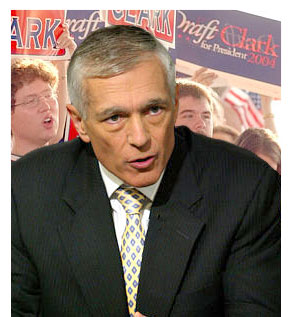

History remembers Gen. Wesley K. Clark as the man who helped negotiate the 1995 Dayton Peace Accords that ended the Bosnian war and, as Supreme Allied Commander of NATO, ran the 1999 campaign to stop the slaughter in Kosovo. All of which may be good training for what many believe will be his next move. Because if and when Clark declares himself a candidate for the Democratic presidential nomination, his first task will be to bring peace to the balkanized, warring factions of the all-volunteer Draft Clark for President movement.

The existence of the Draft Clark movement has been a significant factor in encouraging the four-star general to consider tossing his hat into the nominating ring. Led by Washington-based DraftWesleyClark.com, it has secured more than $1 million in pledges (though no cash) for Clark, should he run, and has “platoon leaders” and “ground troops” waiting to be deployed for Clark in all 50 states. With just 25 days to go until the end of the third quarter FEC filing deadline, the group has launched a $5 million pledge drive for Clark. Already, they’ve run radio and television ads in New Hampshire, Iowa, Washington, D.C., and Arkansas to raise Clark’s name recognition and encourage the Arkansan Rhodes scholar and West Point graduate to enter the race.

The group also took a lead from former Vermont Gov. Howard Dean’s campaign and contracted with MeetUp.com, and now boasts more than 11,000 members meeting in 400 venues in 100 cities — more than have been attracted by either Sen. John Kerry, D-Mass., or Sen. John Edwards, D-N.C., though a far cry from Dean’s more than 105,000 MeetUppies.

Then there is DraftClark2004 — the ground machine. Based in Little Rock, Ark., and with a satellite office in New Hampshire, DraftClark2004 is the nascent field operation working to supplement DraftWesleyClark’s buzz machine. It’s got five full-time staffers and more than 108 field coordinators who hold weekly conference calls and prepare to get Clark on ballots and endorsed by local officials. There are plenty of other Clark groups, too. The ClarkSphere, based in Boston, operates as the technical arm of the Clark movement, providing Web expertise to all the Clark organizations and recently launching United for Clark, a Web page to bring the disparate Clark factions together under one roof. Women for Clark adds marketing expertise and a different voice to a movement that is, like the military, overwhelmingly male.

As Clark gears up for a probable announcement by Sept. 19, interviews campaign staff, and makes nice with potential funders, he also faces the further, unique challenge of figuring out how to insert himself into the core of a movement that has sprung up and run itself for more than six months without him or any central command, and whose members back him more than they do each other. And not only will he have to smooth over the rivalries between the groups, he will also have to figure out what to do about “Clarkism,” an almost mystical philosophy expounded by some of his most ardent supporters that seems antithetical to the kind of straight talk necessary to win a nomination contest. And he will have to figure out if his most loyal fans will in the end be a help — or an embarrassment.

“The interesting thing about the movement is that there are a lot of nodes of activity that have developed organically over time. A lot of these relationships and a lot of the legwork will have already been done,” says an enthusiastic Jeff Daily, a 32-year-old devoting himself full-time DraftClark2004 in Little Rock. From the perspective of DraftClark2004, it’s all about taking “the movement” from the Web to the real world, rather than running ads or getting more press attention.

“We’re at the point now where there doesn’t need to be any more buzz about General Clark. People know about General Clark. We just want to have some foundation there that he can take advantage of,” says Brent Blackaby, national coordinator for DraftClark2004 and a former fundraising aide to Democratic National Committee chair Terry McAuliffe. “It’s great to have an Internet team, but we have to be able to go from clicks-and-mortar to bricks-and-mortar,” adds Daily.

But talk to Clark’s buzzmaster in chief and you’ll get a very different view about the relative importance of free media in a race where Clark has only 40 percent name recognition, even in New Hampshire. “I think some folks may be talking too big a game,” says John Hlinko, co-founder of DraftWesleyClark.com. “Once the general runs he needs to call the shots and run his own campaign. Anyone who claims they are going to run a turnkey operation is being a little bit silly. Anyone who says it’s going to just flip over is overstating it.”

The tension with DraftClark2004 — or “20-Oh-4,” as it’s called by insiders — stretches back to when DraftClark.com, one of the first Clark Web sites, was relinquished by its founder, Markos Moulitsas Zuniga, a 31-year-old former U.S. Army soldier turned lawyer turned Dean campaign technical consultant. Moulitsas jump-started the Draft Clark Movement earlier this year before finally giving up on Clark after months of waiting for him to declare — and after Dean campaign manager Joe Trippi invited him to work with Dean. Moulitsas (also known as Kos, of the Daily Kos blog) wanted the 20-Oh-4 people and Hlinko to share his old site, but the Arkansans wanted to buy it proprietarily and tried to block Hlinko’s involvement, says Moulitsas. This so annoyed Moulitsas that he gave the site to Hlinko for free.

“I do not like the DraftClark2004 people. There’s two competing movements and I don’t know how close they work together,” says Moulitsas. “I’ve dealt with John Hlinko and I think he’s a real class act and if Clark runs I hope they work closely with Hlinko.”

A small man with a dark goatee, Hlinko (the “H” is silent) is of Greek-Lithuanian extraction and a New Yorker by birth and temperament. If you haven’t already realized that he’s become the loudest voice in the Clark movement since joining up in April, he’ll make no bones about telling you: “Not to disparage the other groups, but to describe who’s driving the movement — not to sound hubristic — it’s us.”

The effort to draft Wesley Clark is only one of the many high-profile, online projects he’s engaged in over the years. He’s also the “Action Hero,” according to his business cards, of ActForLove, a personals service for liberal activists whose motto is “Take action to get action.” In 2001, he was profiled in Salon for his “activist high jinks.” He started the “Just Say Blow”online petition campaign against the Bush administration’s decision to deny federal student aid to students convicted of drug possession or dealing. That stunt also got him interviewed on Fox News and went so far that his group, Students for a Drug-Free White House, even launched radio ads. In 2001, he worked on the John Cusack for President campaign. That same year, he dressed up as a pile of laundry and delivered a pro-campaign finance reform petition to Sen. Mitch McConnell, R-Ky., for MoveOn.org, for which he had done some publicity work back in 1998. In 1997, he was hauled into court in San Francisco, according to the San Francisco Chronicle, with a group called “Multimillionaires for Corporate Welfare,” which satirized a ballot initiative for a new stadium in a manner potentially confusing to voters. At the time, his business cards said he was a “comedy writer/model American.”

For all Hlinko’s stunts, he’s been profiled in “Getting Your 15 Minutes of Fame and More!” he boasts proudly on his Web site. A review on Amazon.com says the book will teach readers to “discover the ease of becoming famous” and demystify “the process of obtaining free publicity.”

In short, if you want to run an online petition drive coupled with advertisements and get loads of high-profile publicity for an improbable cause, Hlinko is clearly the man to hire.

Today, Hlinko runs his latest foray into the limelight out of a one-room office in a larger suite inhabited by former Clinton White House press secretary Mike McCurry’s online public affairs firm Grassroots Enterprise. Three men staff the organization on a regular basis, plus college interns and volunteers. A sign on the wall instructs them to remember the “Three M’s: Media, members, money.” A giant map of America graces another part of the wall, small American flags stuck into it in every city where there are “local platoons.” A banner above the computers reminds, “It’s the DRAFT, stupid!” while boxes of Clark bars (a candy that tastes like “chocolate-covered barley,” says Hlinko) and DraftClark ’04 beer steins have accumulated in corners, waiting for distribution to local MeetUp members.

One of the group’s other leaders is Josh Margulies, a Republican attorney from New York City who ran for mayor of Utica, N.Y., at age 24 and voted for Clinton twice. He also happens to be Hlinko’s brother-in-law — and is on friendly terms with Clark’s son, Wesley Clark Jr. (Keeping it in the family, one summer intern was Hlinko’s cousin.) Chris Kofinis of ISE Consulting signed on in August and has written strategy memos for the group, and Eric Carbone, a previously retired 33-year-old dot-commer who sold his Real Sports Fans Network to AOL, designs and manages the group’s online presence.

“There’s something about Clark; when he’s up there, hardened, cynical people get the sense he should be president,” says Hlinko over lunch — for him, an order of fried liver with onions, at D.C.’s Old Ebbitt Grill. “It’s not a question of if we want to be electing a wartime president,” adds Margulies. “We’re electing a wartime president because we are at war.”

Why the drafters are backing Clark is a question that elicits many different answers. Movement members don’t just talk about his national security bona fides, his liberal domestic positions, or his formidable logistical expertise, though. They also talk about Linus Torvalds.

Torvalds, the father of the open-source software system Linux, is a hero to the online Clark community, which is developing a new political philosophy called “open-source politics.” Stirling Newberry, a 36-year-old computer consultant, is the unofficial theorist of the Clark movement, a regular blogger over at the ClarkSphere, and maintainer of Zuniga’s old site, DraftClark.com.

“If you’re annoyed about something in the Dean message, good luck going to Joe Trippi and getting it fixed,” Newberry says. He expresses frequent annoyance with the Dean campaign, which he says rebuffed his offers of help some 18 months ago. “The Clark movement is a movement based on a person with an idea. Wesley Clark has articulated a vision and it’s the job of the Clark movement to put that vision forward in a variety of ways to bring people in and say, ‘We do things a certain way here, and if you do things that way you’ll be welcome and your work will be disseminated to everybody.'”

In short, the philosophy of the Clark campaign is “into the center and out again.” It’s not mainframe politics — the traditional top-down campaign. And it’s not Microsoft, which is the Dean campaign, providing an easy-to-download, endlessly modifiable platform for voters but remaining at core anarchic and lacking a strong message.

(Trippi has told Stanford University law professor and blogger Lawrence Lessig, in an interview, that he does see the Dean campaign as the first open-source campaign, but Newberry insists Dean is really running the Windows campaign.) “The Clark campaign does not have a tight campaign,” continues Newberry. “Wesley Clark has been running for over a year and he wanted to have time to talk about ideas. He said, I won’t run unless I have a chance to talk about ideas. He began a campaign to become a public figure. He founded Leadership for America, he raised his public profile, and once he became a public figure, he wanted to see if that would be enough to run for president.

“Clark, like Torvalds, gave a way of creating a movement,” he adds. “You don’t need to have this great polished final thing, you need to have a basic thing. People will fill in the other things. It’s not about just an individual person; it’s about a very simple core of ideas about institution building, about leadership, about people taking responsibility.”

In short, the philosophy that has been developed is one ideally suited to a movement without a leader and to a leader without a well-articulated set of policy positions. And so the Draft Clark for President movement — a movement, on it’s surface, that is about a specific man and a specific position — is held by many of its adherents to be about freedom from the politics of personality and to be more about the systems of governance and their legitimacy.

“Clarkism is not about an individual,” explains 25-year-old Matthew Stoller, former Kerry volunteer and recent Harvard graduate who runs the ClarkSphere with Newberry. “It’s not Dean for America, it’s leadership for America. It’s not an embrace of the man, it’s an embrace of the ideas he suggests, and an embrace of Clark’s vision is an embrace of what we love about America, what we always felt in our hearts was the America we really wanted to live in … The absence of personality in the Clark movement attracts people who are not interested in personality; they are interested in ideas.

“If you place your faith in an individual,” Stoller continues, “then you are not placing your faith in systems like the rule of law. The Clark people place their faith in systems. That’s why institutional legitimacy is so important to Clark — the institutional legitimacy is about systems, about placing ideas in their legitimate forms, which is institutions. America is the actualization of the Enlightenment through institutions.”

If all of this sounds a bit academic and abstruse for a movement that’s going to need to attract voters, Moulitsas says not to worry. “Dean freaks are the ones who built the whole movement,” he laughs. “Don’t make fun of the [Clark] freaks. We need the freaks.”

The people who sound so fuzzy-headed right now are the same ones who are organizing the mechanisms that may one day assist Clark. That’s the paradox of a grass-roots campaign. There is always both more and less there there than there appears to be. Stoller isn’t just dragging out his Derrida in conversation, he’s mass e-mailing a new daily update about the Clark movement, the Clark Tribune, to anyone who’ll sign up for it. And in that forum he’s not the Harvard history student, but the chipper Harvard Lampoon writer, as silly as he wants to be. In a recent e-mail, he included a vinaigrette recipe he thought Gen. Clark might enjoy.

“One of the strengths of the Draft movement, of any kind of grass-roots movement, is people can use their own initiative to promote a candidate,” says Moulitsas. “The worst thing to do is impose a top-to-bottom organization, because once you do that people will lose their incentive. Nobody likes to be told what to do, especially if you’re doing something for free.”

And, he might have added, doing it for free for someone who is not yet even a candidate.