The helicopters were indeed black, and when they came thwocking through the clear blue skies above Redmond, Ore., on the afternoon of Aug. 19, Don Berry happened to be having a slow day selling campers and fifth wheels at Courtesy RV. "We just stood there in the lot, my friend Chuck and me, watching," he says before launching into a bit of detail that government sources will not confirm. "They were Chinook military helicopters -- huge things with round noses. There were three of them, and they were moving in tight formation, lollygagging over the woods, zigzagging near [the town of] Sisters and out toward Black Butte," some 25 miles to the northwest.

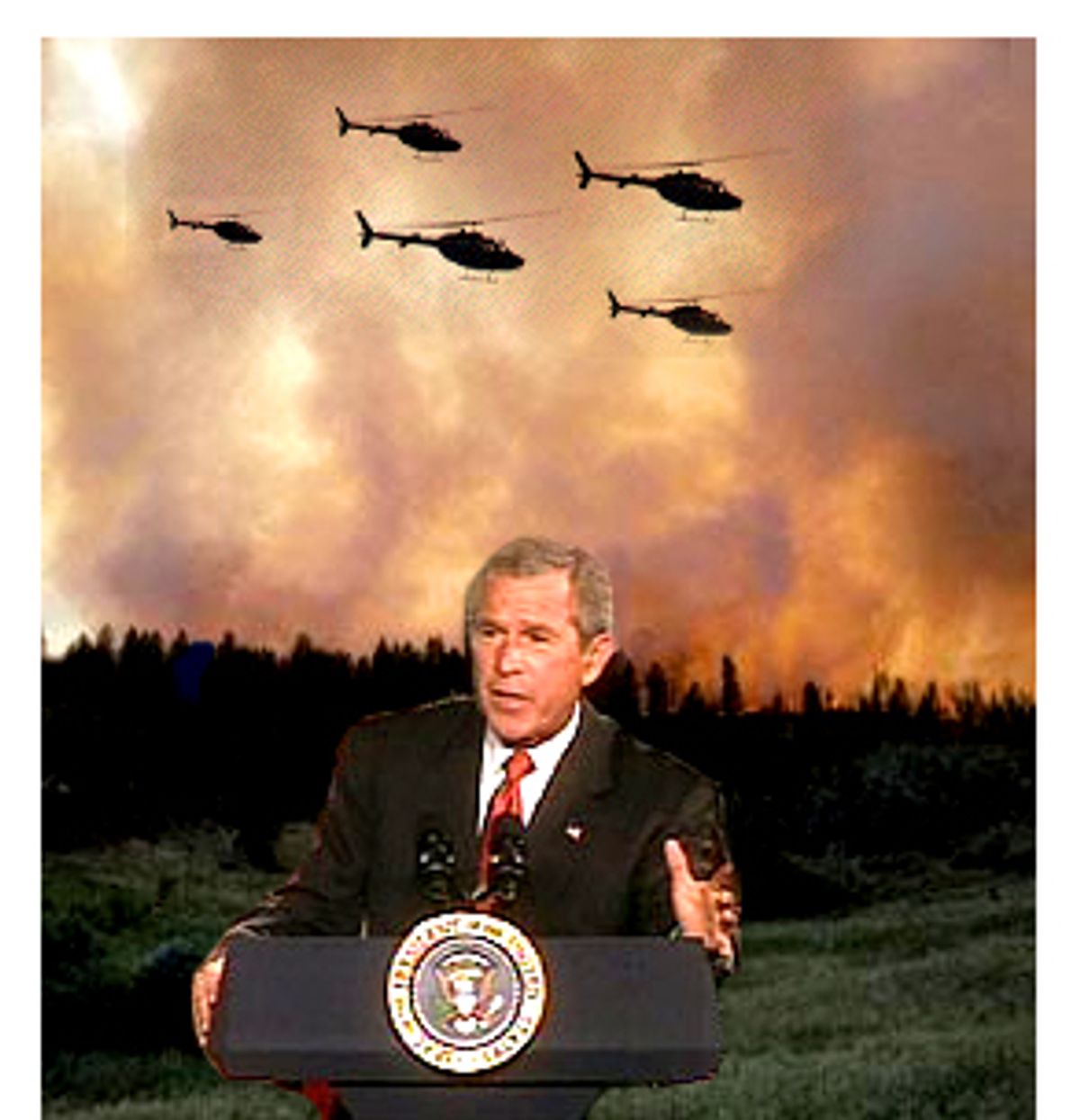

The copters were in Central Oregon, officials from the U.S. Forest Service would later note, to do reconnaissance in advance of an Aug. 21 visit to the dry, wooded region by President George W. Bush. "They were doing routine surveillance," according to Ron Pugh, a Forest Service special agent. The president planned to speak in Camp Sherman, a little town near Black Butte, and to call, controversially, for the "thinning" of 20 million acres of fire-prone public forests.

Don Berry is detached from the fray over Bush's Healthy Forest Initiative, but as the choppers flew near Sisters that day, he gazed skyward for much of their 90-minute flight. "They came right over the top of us," he remembers, "and we watched them land, and then I looked up at the mountains, where they'd flown."

"Chuck," Berry said at that point, "I hope what I'm seeing out there is a cloud."

It was not a cloud. That afternoon, Forest Service lookouts detected high columns of smoke rising from what would soon be called the Bear Butte and Booth fires. The fires were initially about 14 miles apart. They were first noted within two hours of one another -- at 1:30 p.m. and 3:23 p.m., respectively -- and they quickly became sprawling infernos. Still burning, they have now merged and have eaten across nearly 90,000 acres of remote forest dominated by lodgepole pine and Douglas fir.

The "B & B" fires were first noticed 11 days after Central Oregon's most recent lightning storm, and they are now doing battle with 2,200 soot-smeared firefighters, most of whom are camping out on the rodeo grounds near Sisters. The fires have cost taxpayers over $20 million in firefighting fees; forced hundreds of homeowners to temporarily evacuate; closed roads; and thrashed Central Oregon's tourist economy. As yet, though, no one knows how the fires started; no one can say whether the helicopters had anything to do with the flames.

Which means that speculation is spreading like, well, wildfire. On the virtuous, leftmost edge of Oregon's political universe, out where the arugula is organic and the coffee shade-grown, a theory is taking root. Bush's cronies set the fires, supposedly, so as to create the perfect backdrop for the president's speech. It's obvious. Just look at the photo ops he got out of the fires -- at the way many Oregon TV stations appointed their stories on Bush's visit with blazing footage from the B & B fires. When Bush addressed 600 invitation-only Republicans at a resort called Sunriver on Aug. 21 (he was smoked out of Camp Sherman), he didn't even need to allude to the B & B Complex. His pyro henchmen had already ensured that that the videotape did all the talking. The trees gotta go, the pictures were saying, or every forest will burn just like this one.

The W-plays-with-matches theory emerges at a pivotal moment. Bush is now trying to rally support for a congressional bill that would give his year-old Healthy Forest Initiative some teeth. House Bill 1904 -- passed by the House and soon to get a Senate hearing -- would suspend environmental and judicial review of most fire-prone timber sales and would enable loggers to harvest some old growth trees that are not now federally protected. Environmentalists worry that the bill's passage would give the president a ticket to make good on his stated hope of doubling logging in Western forests. They say they're loath to let him market his plan by setting a couple of fires. As is common among liberals and leftists, there is much fuel for their anger -- the 2000 Florida election, the erosion of civil liberties, the Iraq war. Here, environmental issues are especially important. They already hate Bush for weakening the Endangered Species Act and for derailing what they saw as a hopeful trend. Under Clinton, the Forest Service was getting greener. Now the agency is taking direction from a former timber lobbyist -- Mark Rey, the undersecretary of agriculture.

Portland's daily newspaper, the Oregonian, and Oregon Public Broadcasting have given serious coverage to the argument that Bush allies may have set the fire. But larger environmental groups such as the Oregon Natural Resources Council have shied away from it, perhaps for fear of appearing paranoid, and so the conspiracy theory may never get a full hearing outside of a few funky cafes.

Randy Wight doubts the helicopters had anything to do with the flames. Wight is a captain for the Deschutes County, Ore., Sheriff's Office and the coordinator of the Central Oregon Arson Task Force, which is now single-handedly investigating the B & B fires -- and planning to release a report on their cause next week. "I don't have any indication that it was political arson," Wight told me. "The only people discussing that is the media." Wight went on to say that the fires could have been started by a lightning strike whose fire smoldered for days, held in check for a time by the rain that came with the thunder. "Humans could have ignited the fires accidentally," he added. "We really just don't know what started them, and at this point we're not foreclosing any possibility."

The task force is a 15-year-old group comprised, in part, of reps from the Forest Service, the Bureau of Land Management, the Oregon State Police and five local fire departments. Environmentalist Joe Keating is dubious of the group's claims to neutrality. "The fox is guarding the chicken coop," says Keating, the issues coordinator for the 500-member Oregon Wildlife Federation. (He is also a part-time issues coordinator for the Sierra Club.)

Keating notes that, if the fires are deemed to be human-caused, investigators will then take direction from the agency whose land is burning -- in this case, the Forest Service. And, he argues, "the Forest Service has a vested interest in saying it wasn't arson. Their boss, Mark Rey, likes Bush; he likes the Healthy Forest Initiative."

Keating has made a solo, and as-yet unheeded, call on the FBI and the Oregon governor's office to launch their own investigations of the B & B fires. "I smell a rat," he says. "These fires were the perfect backdrop for Bush to talk about his forest plan."

Keating, 60, is a former Army lieutenant and investment banker who lives near me in Portland, riding his bicycle everywhere, a fisherman's hat askew on his sparse horseshoe of white hair. Over the years, he has helped launched Oregon's Pacific Green Party and also headed up a "Yellow Bikes" program, which saw him scattering unlocked, donated old bicycles around Portland, so that pedestrians could hop on, gratis, and ride. He is a socially nimble fellow who has at times slipped into a gray suit and tie to lobby in Washington, D.C. But in his pursuit of fire justice, he has enlisted some rather fringy and colorful scouts to search for hard evidence. One of them is named Russ Taylor; I called him too.

"I'm backing up a logging road at the moment," Taylor said over his crackling cell. "I'm following up on a credible lead from a woman here in Detroit, and --"

"Detroit?" I asked. Detroit is a small Oregon town over 20 miles northwest of where the B & B fires started.

"This woman," Taylor continued, undeterred, "used to work for the Forest Service. She was the secretary for this guy who was a real 7-foot timber beast -- they called him Chainsaw Dave -- and her son, he was out in the woods here and he saw a young man in his 20s. This is way out in the middle of Bumfuck, Egypt, and the young man was wearing a blue, lined fleece jacket. Now, I've been around pilots and that's what they wear." Taylor alleged that the pilot was a Bush operative, and that he touched down to set fires.

"But what difference does a fire in Detroit make?" I asked.

"You make it look like there's a pattern," Taylor explained. "You set a fire here, you set a fire there, and then everybody just says, 'Oh, it's just a dry day. The woods are burning all over the place.'

When I remained unconvinced, Taylor continued emphatically: "Look, we can't give you a smoking gun on a silver platter. I'm sorry, but if you're a real investigative reporter, you'll need to do some digging around. You'll need to go out to Sisters yourself."

He was right, of course. I packed and got in the car.

The drive east from Portland, over Mount Hood to Sisters, 160 miles away, is essentially a journey from green, fecund lushness into a tinder box. You ride up through the rain shadow of the Cascades, and then, soon after you begin rolling down the east flank of Hood, the grass by the roadside becomes tawny and wispy. The smell of sage is pungent, and the woods are piled with the downed trunks of spindly, brittle dead trees. Here and there you see stands of completely charred forests: naked black trees straight and limbless as telephone poles.

Like much of the American West, Oregon has felt the ill effects of Smokey Bear and his 50-plus year campaign to tame nature and its inevitable wildfires. Though the Forest Service now manages "controlled burns," many long-suppressed blazes are erupting with a coiled vengeance. Hundreds of thousands of forested acres have burned in Oregon over the past five years. House Bill 1904, co-sponsored by Rep. Greg Walden, R-Ore., is a direct response to what he calls "catastrophic wildfires." It's also a sort of litmus test in ever-evolving Central Oregon.

The region, which encompasses Bend, population 52,000, and six or eight much smaller burghs scattered across the western fringe of Oregon's expansive high desert, is emblematic of the new American West, where, mountain bikers, vegans and tourists commingle with rock-ribbed loggers and ranchers. It's a region where the ham and eggs breakfast has been supplanted, in large part, by fresh bagels and cappuccino. The residents get along, mostly; they tend to refrain from frothing on political matters. But a plain fact is that the old stalwarts generally regard HB 1904 as a cool breeze of common sense. The newcomers and their allies tend to see the bill as a manifesto for butchery. They're hoping to find a cigarette lighter with a "W" on it.

Hoping against hope, maybe. Forest arson is a damnably difficult crime to trace. There are no witnesses, typically, and the evidence burns. Ron Pugh, who also serves as an investigator for Central Oregon's Arson Task Force, estimates that his group catches fire starters "less than 5 percent of the time," and he notes that the Booth fire may prove uncommonly tough. The wind has shifted over the ignition point two or three times and the evidence, if such exists, has been quite thoroughly cooked and recooked.

Once I pulled into Sisters, population 1,080, and became acclimated to the smoky haze hanging in the cloudless sky there, I had little choice but to begin my digging at the local organic bakery/cafe, a place called Angeline's. I bought a gluten-free muffin and then wandered back to the green grass of the patio and spoke with the members of a Sisters band called the Blue D'Arts, who were setting up to play an evening of acoustic folk.

"You'd think it wouldn't be possible," said the D'Arts' lanky guitarist Dennis McGregor, "that Bush would start a fire just to be expedient. Would he really that be that deceptive, that cruel? Yeah, that's how he does everything -- the election, for instance."

An hour or so later, McGregor was inciting the crowd. "Was it a brush fire or a Bush fire?" he crowed from the stage. "Who started the fire?"

"Bush!" The response was unanimous, and rather spirited. Angeline's has a beer and wine license. By dusk, in fact, there were about 50 people sipping away in the cool evening air. I wandered among them. Several folks spoke of seeing three Marine One helicopters flying over the now-burnt areas early on the afternoon of Aug. 19. "They were flying so low, it was scary," bartender Karly Lusby told me.

Up the street at a bar called Bronco Billy's, a somewhat schnookered source, speaking on the promise that he would remain anonymous, told me that a Forest Service lookout spoke of the copters over his radio -- and then heard his boss say, "You didn't see that." The story echoed something I'd read in an e-mail Russ Taylor forwarded to me -- an anonymous note about a "guy ... working in the woods" who suddenly found his cell phone inoperable, the signal scrambled, as the copters flew overhead.

I wanted something a little more solid, so I went back to Angeline's and spoke to co-owner Henry Rhett, who, I'd been told, had the skinny on some timing devices supposedly found near the spot where the Booth fire began. "I feel sheepish even mentioning it," he told me, "because what I heard was like fifth-hand."

I decided, at this juncture, that I needed a drink. I ordered a Mirror Pond ale and then, luckily, found someone who could elucidate the rumors swirling around me. Bonnie Malone, 56, is a chiropractor/social activist who is arguably the dean of Sisters' liberal community. (The Chamber of Commerce named her "Citizen of the Year" for 2002.) "People here are scared of what's going to happen if House Bill 1904 passes," she said. "Timber companies have stolen from the woods near here before."

Malone noted that many Sisters residents still remember Layton and Bartlett, a Bend logging firm whose principals were, in 1990, found guilty of illegally cutting 1,800 trees -- federally protected old-growth -- about 10 miles south of Sisters. James W. Layton and Frederick W. Bartlett each drew 18 months in federal prison.

Now the loggers are "after our old-growth again," Malone said. "It's hard not to be skeptical of a forest plan that bypasses environmental review. Why do we have to cut these trees down so fast, without even considering the facts? Didn't we just rush into the Iraq war like that?"

Malone wore a denim jacket and peace symbol earrings, and as she leaned toward me and spoke, her manner was quiet, concerned. She took pains to convince me that Sisters was not split asunder by forest politics. "Most of my friends are Republicans," she said, and then she pointed me toward the most ardent among them.

John Zapel, 39, was reading a book on the aerospace industry when I met him the next day in the vinyl-upholstered booth of a Sisters restaurant called the Gallery. "I'm a nerd," he told me. "I'm the guy who carried a briefcase in high school." Pale-complected with sandy blond hair and glasses, Zapel ran a logging company until last year, when he sold his equipment and became, reluctantly, a logger for hire and a part-time lecturer on topics like "fuel load reduction" in dry forests.

"It was those guys who never take showers that drove me out of the business," he said. "Earth Liberation Front types. For 10 years, I got vandalized constantly. The last time they did $420,000 worth of damage to my harvester. They burnt it to a crisp and then they wrote all over the cab: 'Stop Killing Trees.'" Zapel showed me some pictures of the ruined machinery. "The lunatic fringe does exist," he said, "and that's the first place I'd look now. It's a good bet that these fires were set by ELF or some goofy thing like that. Consider their track record -- the apartment building they burned in San Diego, that ski lift at Vail."

I couldn't fathom why enviros would burn trees.

"The president's coming and they believe in disruption of process. They're saboteurs." Zapel stabbed a fork at his french fries. His right hand was missing two fingers, thanks to an ax. "Eugene is just two hours away," he reminded me, "and that's the premier bastion of the whole anarchist movement."

Eventually, Zapel and I stepped outside, onto the sidewalk. The smoky haze was still there, and the sight made him angry. "The most disgusting thing to me is that this didn't need to happen," he said. "We could've gone in there and thinned. We could've reduced the fuels on those forests. But now they're gone, and for the next 40 years we're staring at a Holocaust. That's sad for everybody." Back in Portland, I talked one last time with Joe Keating, of the Oregon Wildlife Federation, and his scout Russ Taylor. We met for morning coffee, and Taylor, a 50-something freelance photographer, showed up at the cafe wearing a white straw Stetson. In his arms, he bore an aerial photograph he'd taken of a forest ravaged by clear-cuts. "The pilot who flew me that day died a very mysterious death soon after the photo was taken," he said. "His plane crashed just after takeoff, and there were no mechanical problems."

"Russ," Keating implored in soothing tones, "Russ."

"Yeah, I'm one of those conspiracy theorists," Taylor continued, "and this goes real deep for me. It goes back to when a logging truck ran over my dog when I was 4. It goes back to when I was 8 and a bunch of redneck kids stole the hunting knife my father gave me as he was dying."

Keating had both elbows on the table now, and he was cradling his bald head in his hands, his brow wrinkled as he looked down at a newspaper. Here was a man trying to do something very old-school and American (it was Thomas Jefferson, remember, who championed "unremitting vigilance"), and yet he was finding himself mixed up with what he gently called "loose cannons and wing nuts." What on earth enabled him to soldier on?

Optimism and chipper resolve. "We want to get to the bottom of this quickly," he said, "before the trees are all gone, and I'll tell you, if that report comes out and it says the fires were not arson, then I'll scream and yell. Then I'll bring in the Sierra Club and all the other big groups and we'll say, 'This is exactly why we called for an independent investigation.' If they say it is arson, then I ask questions: 'Are you considering political arson? What is your time frame?' If the smell increases, I increase."

Keating grinned. "These fires are my favorite thing to talk about right now," he said, "but I gotta go." He tapped his newspaper, rolled now, against the table one time and then he stood up, a sturdy old guy in a T-shirt with a picture of an artichoke on it, and he strolled away down the street toward his office. His campaign to "shine the light of truth" on the planet's most powerful political figure was still on.

Shares