New York may be a wildly Democratic city that chose Al Gore over George W. Bush by a 4:1 margin in 2000. But that didn't stop the White House from forming a close bond with the city during its darkest hour.

In the wake of the Sept. 11 attacks two years ago, Bush swiftly reassured New York City's traumatized citizens that the nation, and the federal government, would remain by the city's side as it tried to stagger back from that unprecedented strike on civilians. "I can't tell you how proud I am of the good citizens of [New York] and the extraordinary job you all are doing," Bush told New York Mayor Rudolf Giuliani and Gov. George Pataki, during a televised Sept. 13, 2001, conference call, soon promising $20 billion in recovery aid.

The next day Bush made his stirring visit to ground zero, draping his arms around New York firefighters and standing on the remains of a fire engine, where he shouted from a bullhorn that "the people who knocked down these buildings will hear all of us soon."

"The rallying he did around New York, saying we're all in this together, that was an important aspect of the aftermath of the attacks, and it was well done," says Rep. Jerrold Nadler, D-N.Y., who represents Manhattan. Bush's popularity soared in New York, a traditional bastion of political liberals, and remained high for well over a year. But Bush's standing could suffer next year when the Republican Party National Convention convenes here, its date pushed back from August into early September -- ending just days before the third anniversary of 9/11.

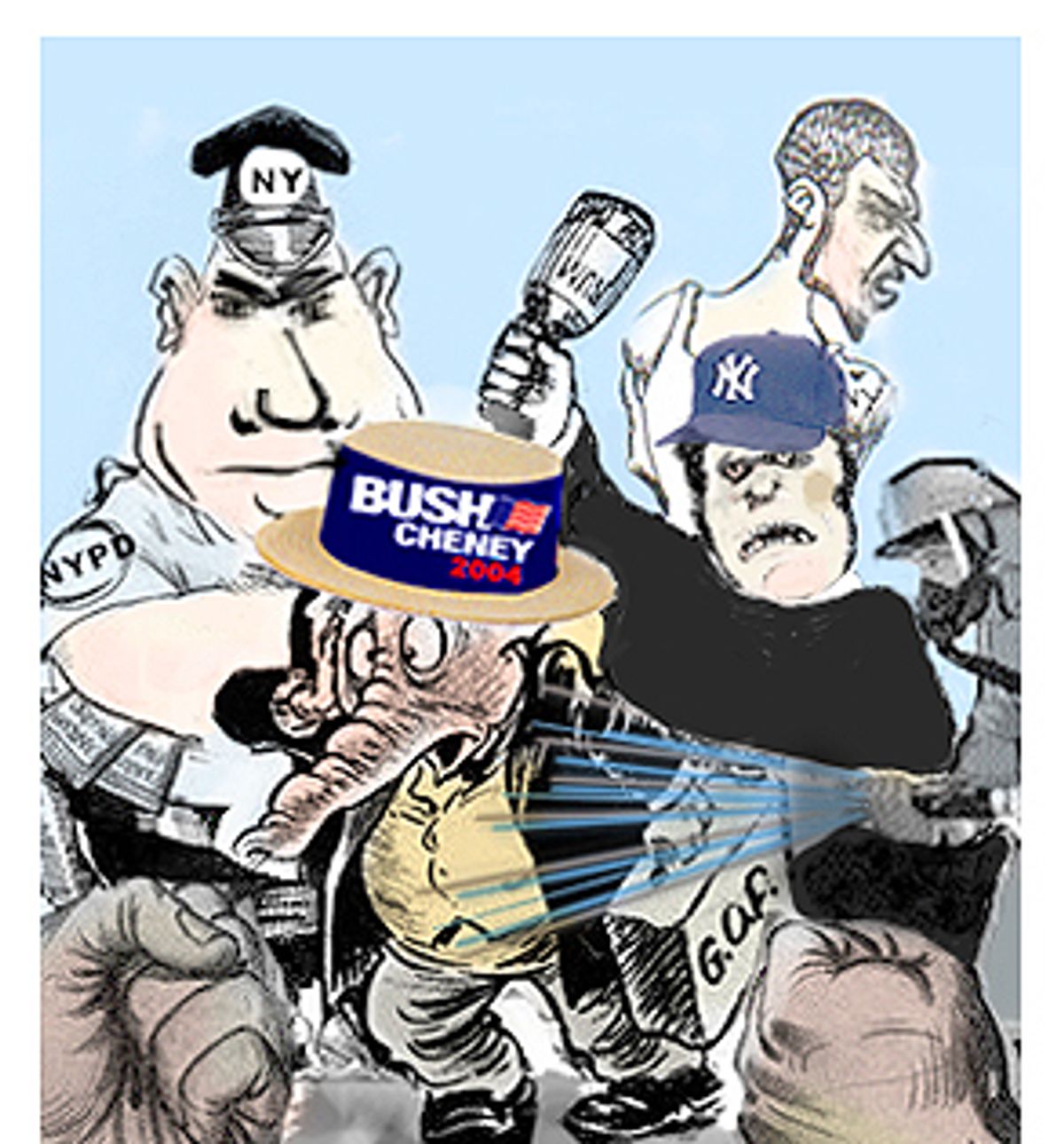

It doesn't take a jaded Bush critic to wonder if the president's handlers plan to use the moment not just to stage a celebration of the president's first term, but also to exploit the tragedy that happened just blocks away from where Republican delegates will gather. How successful that would be, of course, depends on this administration's accomplishments in reviving the economy and waging the war on terror over the next year. But there are already a raft of critics in New York ready to express their disappointment -- and for some, anger -- at the president's post-9/11 treatment of the Big Apple.

Some community activists and elected officials claim the White House has all but turned its back on New York as it struggles to rebuild its downtown area physically and economically, and as it wrestles with the long-term health and environmental implications of the terrorist attack.

"The White House has used Lower Manhattan as a campaign springboard for the president's reelection in 2004, and nothing else," says Margarita Lopez, a Democratic city councilwoman who represents that part of Manhattan. "I was willing to give them the benefit of the doubt months ago, but no more. Dealing with this issue has been partisan from beginning to end."

Adding to the bitter aftertaste was the stunning revelation late last month, that the Environment Protection Agency, at the prompting of the White House, had misled New Yorkers by publicly insisting in the wake of the twin towers' collapse that breathing the polluted air in Lower Manhattan posed no health risk. That insistence came despite EPA's having done no testing whatsoever on the air quality. Subsequent analysis has proved the air to be quite toxic.

The report, conducted in-house by the EPA's inspector general, suggested that the White House, anxious to paint a portrait of normalcy for America in the wake of the surprise attacks, and wanting to reopen the New York Stock Exchange as quickly as possible, pressured the EPA to make those too-good-to-be-true health assessments.

"They're still lying about it, they still haven't cleaned it up, and slowly people are being poisoned every day," complains Nadler. "More than half the [9/11] rescue workers tested already report restrictive airway diseases. People [in Lower Manhattan] will be coming down with diseases, with lung cancer, for 15 to 20 years, and Bush will be responsible for that. Because instead of properly cleaning things up, the White House buried its head and lied because it didn't want to pay for the cleanup."

The EPA is scheduled to get a new chief, but Sen. Hillary Clinton has announced she'll block the pending nomination until she gets answers about who was responsible for instructing the EPA to mislead New Yorkers about the air quality.

And while New York critics concede the White House has, for the most part, kept its word by allocating $20 billion toward the city's cleanup and reconstruction effort, it's been minimally effective: The terrorist attacks inflicted an estimated $80 billion to $100 billion worth of economic damage to the city.

"There are very few indications the Bush administration has done anything extraordinary to help New York," concludes Rep. Anthony Weiner, D-N.Y. "We shouldn't have to fight to ease the burden of digging out of this horrible mess. Especially since it was a federal [intelligence] lapse that allowed us to be attacked in the first place."

A White House spokesman did not return calls for comment. Neither did the press office for New York's Republican mayor, Michael Bloomberg.

The city's dissatisfaction with Bush was reflected last week in a New York Daily News poll that showed 56 percent New Yorkers disapprove of the way he is handling the war on terrorism and think the city is less safe than it was two years ago. Only 20 percent say they will vote for Bush in the next election (he received 19 percent of the city's vote in 2000).

Two days after the 9/11 attacks, New York Sens. Hillary Clinton and Charles Schumer, both Democrats, consulted with Giuliani and Pataki on how much they should ask for in federal aid. They came up with the round figure of $20 billion. Meeting that afternoon in the White House, Schumer, as he has told the story, expected Bush to counter with an offer of $5 billion. Instead the president never flinched at the $20 billion request and told the New York delegation, "You got it." (The final figure was closer to $21 billion.)

Two years later though, the disaster-relief money has been slow to flow. "I didn't realize how difficult it would be to get money released from Washington," says Rep. Carolyn Maloney, D-N.Y.

"You'd think with a Republican governor of New York and a Republican mayor, it would have helped greased the skids, but it has not," adds Weiner, who suspects politics is behind the White House's lackluster response. "Because [political advisor] Karl Rove made the correct assessment that Bush isn't going to win New York, so why waste the capital?"

To date, approximately $5.5 billion has gone to the city and its entities, according to Adam Blumenthal, the city's first deputy controller. "Most of that has been for reimbursement for direct expenses in cleanup and some support for residents, as well as small and midsize businesses."

Meanwhile, $11.5 billion remains in the pipeline, tied to long-term projects such as rebuilding the transportation and city infrastructure. That money will be released when various construction ventures begin.

But the controller's office warned last week that the remaining $4 billion is "at risk" and may go uncollected, in part because of how the federal aid package was crafted.

The $20 billion parcel was quickly passed by Congress in the wake of the attacks, but not before its physical form was negotiated with the White House. "At first we wanted cash," says Maloney. "But the administration negotiated Liberty Zone tax incentives."

The idea was to stabilize the economy of New York City and keep jobs in Lower Manhattan, by enticing people to return to the devastated area through tax breaks, such as a $5,000 tax credit to residents who pledge to stay in the area, and a $2,400 per year tax credit for each job created or retained. The Liberty Zone represents $5 billion of the $20 billion aid package, but comes in the form of potential tax cuts, not an infusion of cash.

The problem is that the zone was based, in part, on overly optimistic projections about the demand for commercial property downtown, says Blumenthal. He explains that developers face a deadline of December 2004 to begin selling bonds for construction projects in order to qualify for the tax incentives. As a result, nearly $4 billion may go uncollected and essentially evaporate from the city's coffers.

"We're extremely disappointed," says Blumenthal. "We're not questioning anybody's good faith. But at the end of the day there was $90 billion worth of economic damage done to the city."

Maloney is upset that small grants handed out to 9/11 victims, such as the $37,000 payment to the owner of a hair salon located inside the World Trade Center, are not tax free. She says the IRS's after-the-fact decision to tax the grants came as a surprise to New York's congressional delegation.

Maloney has written to the president, the secretary of the treasury and the speaker of the House; and she has tried, unsuccessfully, to introduce an amendment in the Republican House to get rid of what she claims is an unfair tax that has cost recipients $265 million. "I find it hypocritical for this administration to call for permanent tax cuts, yet they've finally found one tax they like -- taxing grants to victims of 9/11."

While at first many regarded the Republicans' decision to bring their National Convention to New York as a goodwill gesture -- the convention will bring in more than $100 million in revenue for the city -- skepticism has steadily grown.

According to press reports, Republican officials hoped that during the event they could place the cornerstone of the proposed 1,776-foot spire at the focal point of the ground zero reconstruction. "We shouldn't be doing anything like laying a [9/11] cornerstone during the convention," says Maloney. Republicans later denied the reports.

For the GOP, hosting the convention in New York City "could send a message that Republicans are strong on national defense, which plays to their strength," says Michael Franc, vice president of government relations at the conservative Heritage Foundation. "But if it becomes too much of an issue -- is 9/11 being exploited? -- the president could end up on the wrong side of that and having to play defense."

Ariel Goodman, president of From the Ground Up, an advocacy group for small-business owners in Lower Manhattan, suggests that come next September, the post-9/11 New York City economy, and specifically the conditions in Lower Manhattan, will be in such poor shape, Bush will wish he weren't in town. That's because FEMA housing loans, which paid 100 percent of the rent and mortgage of 9/11 victims who could prove a 25 percent decline in income, will have ended, while payments for Small Business Administration loans handed out after Sept. 11 will become due.

"It's going to be a one-two punch over the next six to 12 months when we're going to see the real economic damage to New York City," says Goodman. "People who've been hanging on by a thread will be go belly up left and right, with a spike in store closings and bankruptcy protection filings. Then Republicans won't be able to claim a success and use the city as a political platform."

For Bill Harvey, a 9/11 widower whose wife of one month died on the 93rd floor of 1 World Trade Center, it's the potential spectacle he fears. "I'm going to be really upset if they try to politicize this thing," he says. But the Bush administration's use of 9/11 as justification for a war with Iraq has left him preparing for the worst. "Some events I think should transcend politics. And 9/11 is one of them. I'm skeptical of this administration, though, because it has shown that nothing is out of bounds for them."

Shares