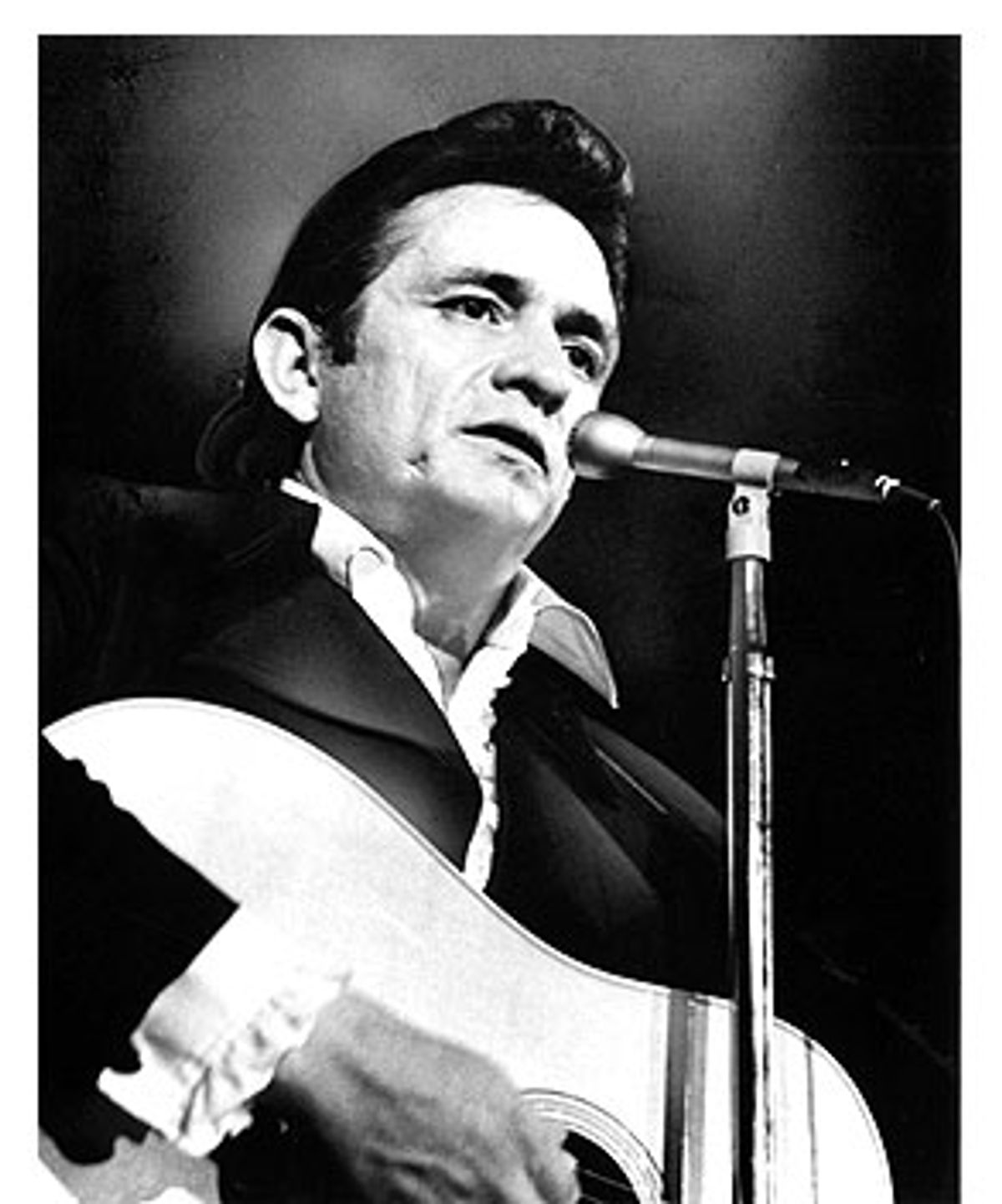

If you took every note that Johnny Cash didn't quite hit and laid them end-to-end, they'd probably reach clear around the world. And so what? His was one of the greatest voices of both country and rock 'n' roll (he's one of the few artists to be elected to both halls of fame), a voice that was beautifully suited to heart-wrenching romantic ballads but that was just as often, or perhaps more often, used to speak up for the downtrodden and the forgotten -- or for anyone who may have simply made a mistake in life. Low and dark, devoid of cream and especially sugar, Cash's voice was the sound of black coffee, a sound you didn't know you needed until you got that first sip. And by then you were hooked.

Cash, 71, died Friday as the result of complications from diabetes; his health had been precarious for years, although it rarely stopped him from working. (His fourth collaboration with producer Rick Rubin, "American IV: The Man Comes Around," was released last November.) Many of us have long been preparing for the death of Johnny Cash, but I suspect most of us aren't finding the reality of it easy to take. And there are many of us out there, of all ages: Cash got his start around the same time Elvis Presley did (and, like Elvis, got his big break through Sam Phillips' Sun Studios). But his career outlasted Elvis' by more than 25 years. His fan base spanned hipster punks and old-time rockers who hadn't bought many new records since 1966. I remember seeing Cash perform live around six years ago, at a rock club in Boston -- in the middle of a snowstorm, no less.

Making our way home, still blissed-out from the show, my husband and I ran into a neighbor of ours, a rather taciturn-looking guy in his late 50s -- who still sported the remnants of 1950s greaser hair -- out in his yard supervising the nightly jaunt of his elderly blind poodle. It was snowing like heck; our neighbor, who'd always been cordial but never exactly friendly, asked us what on earth had brought us out on a night like that. When we told him, his face lit up. Was it a good show? he wanted to know. How did Cash look, how did he sound? The subtext of his questions bubbled up to the foreground: Of course Johnny Cash was worth braving a godawful snowstorm for.

Cash wrapped a world of subjects in that big bear hide of a voice. His love songs could be mournful or witty or both, and many of them were steeped in a deep consciousness of mortality, direct descendants of old English and Scottish ballads about dead sweethearts and infants. "I Still Miss Someone" outlines the shape of the hole left behind by a lover who doesn't care anymore. "I Walk the Line" quivers with restraint -- it's the sound of a very bad boy on his best behavior (and probably not for long, but he sure is trying). "Ring of Fire," which was written by his wife and colleague, June Carter Cash (who died in May), and Merle Kilgore, is one of the most hard-nosed songs about falling in love ever written or sung.

Songs like "Tennessee Flat-Top Box," "Five Feet High and Rising" and "Pickin' Time" are stunning evocations of rural (and often impoverished) life. Cash was a prolific songwriter, but he loved a great song, period, covering the work of Kris Kristofferson, the Rolling Stones, Nick Cave, Nine Inch Nails, Nick Lowe and Bob Dylan (who cites Cash as an essential influence), among others.

But Cash's most lasting contribution may be his rough-and-ready sense of social justice. He wasn't political in the strictest sense of the word. But when something in the world struck him as unfair or wrong, he spoke up with an urgency unmatched by nearly any other artist. His "Singin' in Viet Nam Talkin' Blues" is a rambling account of the trip he and June took there in the late '60s to perform for the troops; the song is rambling not because Cash's thoughts are unorganized, but because even as he's telling us the story of what he and June saw there, he still can't make sense of it -- there is no sense to be made. In "The Ballad of Ira Hayes" (written by Peter LaFarge), he tells, with unvarnished bitterness, the story of a whisky-drinking Marine, a Native American who helped raise the American flag at Iwo Jima, only to return home to a country that couldn't care less whether he lived or died.

And although Cash's signature tune, "Man in Black," isn't technically a protest song, it's still one of the greatest protest songs ever written, a song written and sung in pure anger and defiance. We often sentimentalize the American folk music of the '60s, hailing it as a generation's plea for change, even as we conveniently forget how preachy and finger-pointing most of it was. Cash, perhaps our greatest protest singer (as well as one of our greatest folk singers, although we don't often think of him that way), was never sanctimonious. Instead of just moaning about the troubles of the world, he decided to bear responsibility for them by making a symbolic sartorial gesture, one he stuck to until the end of his life: "I'll try to carry off a little darkness on my back/ 'Til things are brighter, I'm the man in black."

Cash was a religious man, a staunch Christian. But I think you get the best sense of that not from his heartfelt recordings of gospel songs like "Were You There (When They Crucified My Lord)" and "(There'll Be) Peace in the Valley (for Me)," but from the songs he recorded live at Folsom Prison in 1968.

Consider the moment -- a famous one, and one that's both exhilarating and chilling, whether you've heard it once or 100 times -- when Cash sings, in "Folsom Prison Blues," "I shot a man in Reno just to watch him die."

A great wave of cheering rolls forth from the audience, all of them convicted criminals. And although we can't know for sure exactly why they cheer -- and each of them may be cheering for a different reason -- we can make a few pretty good guesses: First of all, the line is grimly funny. Second, some of them may have actually done the same thing themselves, for approximately the same reason -- not a pretty truth, but there it is.

But I wonder if some of them didn't cheer for this reason: Here was a man who freely stood before them, singing in the voice of a character who had committed a crime that was probably colder, and worse, than any of the things they themselves had done. Cash's message wasn't "I'm better than you are." It was "I'm lowlier than you are" -- and with this, he handed them back some of their dignity. Cash sang in defense of the poor, the downtrodden, the unjustly punished. But he also sang in defense of the humanity of murderers. For that fact alone, I hope that the God Johnny Cash so believed in is right there to greet him. If anyone deserves to find peace in the valley, he does.

Shares