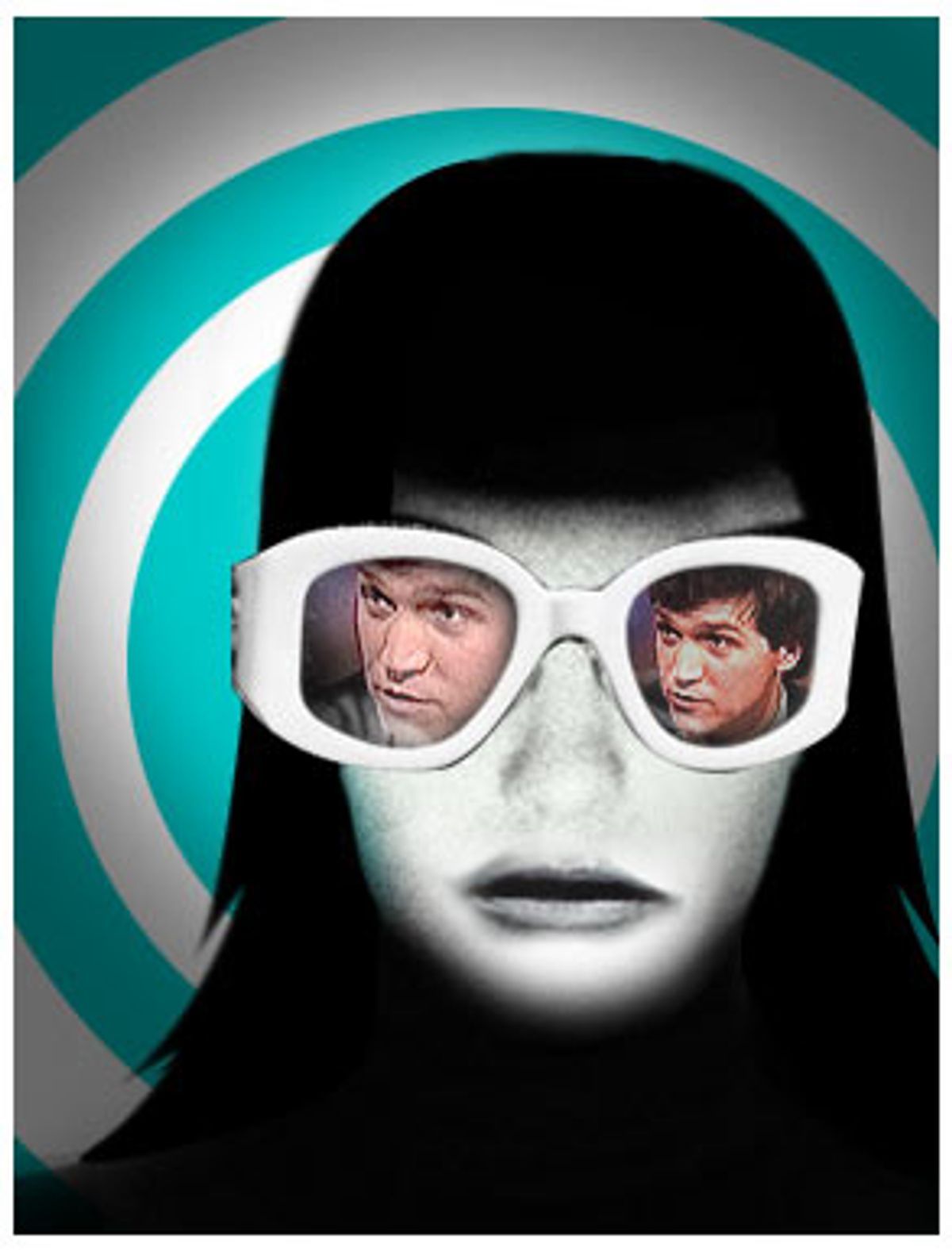

It was June 2001, and I had just gotten off the "Crossfire" set when one of our producers handed me a stack of mail. On the way to the elevator, I glanced at it. On top of the pile was a registered letter from a law firm. It got my attention immediately. I've never had a pleasant letter from a lawyer.

This one was worse than most. It was written by an attorney in Indiana named Paul M. Blanton who wanted to let me know that his client, a woman named *Elizabeth Jansen, was planning to file criminal sex charges against me in the Commonwealth of Kentucky. "Ms. [Jansen] has informed me that she was raped by you," Blanton wrote. "If you should have any questions or concerns about any of the aforementioned, please do not hesitate to contact me."

Should I have any questions or concerns? I didn't know where to begin. Rape? Kentucky? Criminal charges? I knew I hadn't raped anyone. I didn't think I'd ever even been to Kentucky. The name Elizabeth Jansen sounded mildly familiar, though I couldn't recall why. I had the feeling that my life was about to change for the worse. I felt weak.

Then I noticed that the envelope had been opened. My producer had read the letter. She was looking at me in a way that made me uncomfortable, like she'd just discovered a terrible secret. Which I guess she had, but then so had I. I called her into my office and shut the door. I want you to know I didn't do this, I said, I promise. She looked relieved. "Of course not," she said.

I knew CNN wouldn't be as easy to convince. In fact, I knew the network would fire me immediately if it found out about the letter, and certainly if charges were filed against me in Kentucky. The one thing every journalist knows for certain about sex scandals is that they're always true. Partly true, anyway. Maybe you didn't rape this woman, they'd think; maybe you just had unusually rough sadomasochistic sex with her and she misconstrued it. Or maybe your affair with her simply fell apart in an acrimonious way, perhaps over your cocaine habit. Maybe you had sex with her but never knew her name. Something definitely happened between you, though. People don't just make up specific allegations out of nothing.

I went next door to see Bill Press, who was going through his own mail. I showed him the letter. He had two words of advice: "Bob Bennett." Bennett, who represented President Clinton during the early Lewinsky period, is the first lawyer most people in Washington think of when they hear the phrase "explosive allegations." For the scandal-besieged, Bob Bennett is almost a cliché. And for good reason. If you suspect you could be in deep trouble, there's no one better.

I finally reached Bennett on his cell phone an hour later. He was on a shuttle bus heading to the Hertz lot at an airport in the Midwest. He listened quietly. "First," he said, "don't worry. Second, don't tell anybody. I'll be back in town tomorrow. Call me."

I went home and went to bed. At three in the morning I woke up feeling completely out of control. Still half asleep, I was suddenly convinced that somehow I must have raped this woman, whoever she was. I must have done it while sleepwalking or during some sort of memory-erasing seizure. She couldn't have made up the whole thing. Maybe I have a brain tumor, I thought. Maybe I'm leading a double life I don't even know about. Maybe I'm going insane.

I got up and walked downstairs. For an hour I sat on the front steps thinking about my life, my wife and my three children, my job, and how it was all going to end because of something terrible I didn't even remember doing. I felt sadder than I had in a long time.

The next day, I found out more about what I had supposedly done. According to Elizabeth Jansen, whose lawyer relayed the details to Bob Bennett, I was in Louisville, Kentucky, one night two months before. Jansen, an accountant who lives 40 miles away in Mauckport, Indiana, was also in Louisville. We met at Harper's Restaurant on Hurstborne Parkway, where I slipped narcotics into her drink. By the time she awoke, she was covered with blood. She knew immediately that she had been violently raped. By me. In the restaurant. Presumably within view of dozens of other people, not one of whom had thought to report the crime to the police or the press.

It was a preposterous story. I'd never heard of Harper's Restaurant. I'd never been to Louisville. Judging from my schedule in March, I couldn't have gotten there. I was on television almost every night in Washington. Bennett explained this to Jansen's lawyer, Paul "Matt" Blanton. Fine, said Blanton, prove it. In seven days, we're going to the prosecutor. By the way, he added, we have evidence that Carlson and my client know each other. There's correspondence.

*Salon has changed the name of the woman for this excerpt.

Three days later, I took a lie detector test. If you've never been polygraphed, it probably doesn't seem like a very big deal, at least if you're innocent. You answer some questions as honestly as you can, and you leave. That's what I expected. I was wrong. Sitting through a polygraph exam is among the more unpleasant things I've ever done.

Bennett and I waited outside the conference room while the polygrapher set up his equipment. Bennett seemed jumpy. I think he believed me when I said I didn't rape anyone. On the other hand, he once worked for Clinton. He's learned not to take a client's explanation at face value.

The room smelled like a doctor's office as I walked in. Paul Minor, the former chief polygraph examiner at the FBI, greeted me with the solemn formality of an undertaker. Minor has been giving lie detector tests for more than 30 years -- he's tested Anita Hill and Linda Tripp, among others -- and he has the psych-out down cold.

"It's all right to be nervous," he began, as he tightened a black rubber strap around my chest to measure my breathing. "Most people are. There's a lot at stake or you wouldn't be here. People are nervous about losing their jobs, or their reputations or ..." He fixed his watery blue eyes on me. "... Going to prison. If you tell the truth, the whole truth, we'll be fine. If you don't, if you fudge at all, we're going to have problems."

I turned away from him to face the wall, and he began the control questions. "Do you drink coffee?" "Is today Monday?" "Are you in Washington?" It was unpleasant already.

Then he zeroed in. "Have you engaged in any sort of sex act with [Elizabeth Jansen]?" No. "Have you ever forced sex upon any female?" No. "Are you afraid of failing this polygraph?" No.

I mean, yes. I mean, I have no reason to fear failing, since I'm telling the truth, but I fear it anyway, just because failing it would be ...

"Yes or no answers only." Yes. "Would you lie to me if you thought you could get away with it?"

Obviously this was the Zen part of the test. If I were guilty of something and I thought I could conceal it, I would lie. So in general the answer would be yes. Except in this case I wasn't guilty of anything and therefore wasn't planning to lie. I said no. The first time.

Minor took me through the entire list of questions two more times, throwing in an extra one ("Do you ever daydream about having sex with women other than your wife?") just to make me squirm. It worked. Ordinarily I'm not a very tense person, but by the end, I was drenched with sweat. I learned later that Minor once gave a polygraph exam to Woody Allen. I would have paid to see that. I can't even imagine the neurotic energy in the room.

Twenty minutes later I found out that I had passed the test. Bennett seemed jubilant, and very relieved. All that remained was to find out why Elizabeth Jansen was accusing me of a crime, keep the DA in Louisville from bringing charges against me, and prevent CNN from learning about any of it.

The following day, we solved the motive mystery. A private investigator had uncovered a letter from the Norton Psychiatric Center in Louisville concerning its patient, Elizabeth Jansen. Dated less than two years before, the letter referred to Jansen's bipolar affective disorder as "a chronic condition requiring strict compliance to prevent symptom recurrence." Someone had forgotten to monitor her medication.

If I had been paying closer attention, I might have figured this out earlier. Jansen had been writing letters and e-mails to me for months at CNN. Twice she had sent me small gifts, keychains and ballpoint pens. I wrote her thank-you notes both times, hence her lawyer's claim about "correspondence." I hadn't remembered any of this. Later, one of my producers dug up an e-mail Jansen sent me. "I watch your show all of the time," it said. "You are great." Jansen wrote it on my birthday, a month after I supposedly raped her.

It's hard to hate someone who is delusional, and as angry as I was, I was inclined to give Jansen a pass on grounds of craziness. Her lawyer, on the other hand, the weaselly, pompous little Matt Blanton -- I wanted to kill him. At the very least I wanted him to pay my legal bills, which by this point had reached over $14,000, not a dime of it covered by insurance or the network. And I wanted a prolonged, groveling, preferably tearful apology for sending a letter to my place of work accusing me of a felony sex crime.

I didn't get either one. Saul Pilchen, Bennett's able deputy, convinced me that suing Blanton for damages (and I was prepared to spend whatever it took to do it, as long as it wrecked his day) would only draw attention to the original accusation, discredited as it was. In the end, my name would be joined in the same sentence with the word rape, and it was worth at least fourteen grand to keep that from happening. Instead, Pilchen sent Blanton a tart letter pointing out that it's pretty irresponsible for an attorney to make such serious allegations based on the ramblings of a mental patient.

Blanton responded with a snippy letter explaining that his client had "decided to put this matter on hold at this time." As "a respected member and entrepreneur of Harrison County and other surrounding counties," Blanton wrote, Jansen "understands very well the potential ramifications to her personal and entrepreneurial life" of a court case. In other words, Jansen didn't want to embarrass herself by testifying against a rapist like me. It was infuriating.

Almost as infuriating as the letter Jansen herself sent a week later. "I am glad to hear that Mr. Carlson can verify his innocence to the claim that I had made earlier," it began. "In light of the evidence that you provided to me, obviously the person who had assaulted me was not in actuality Tucker Carlson, but an impostor." She said sorry, sort of, and that was the extent of her contrition.

Because, as she went on to explain, she's the real victim here. "I don't appreciate the statements that you made about my mental status," Jansen wrote, launching into a lecture about the need to show sensitivity and tolerance toward people with emotional disabilities. "I am a highly educated individual, with multiple degrees." Yes, she conceded, "I am a manic-depressive." But "everyone of concern knows that this condition can be very well managed. It is usually the ignorant that sensationalize it. There are some very successful people who have this condition. I know many."

In other words, Jansen's craziness may have cost me thousands of dollars and jeopardized my career, my reputation and my freedom. But it was still wrong of me -- "ignorant" -- to suggest that her mental illness might not be such a good thing. Nuts or not, Elizabeth Jansen had a lot of chutzpah.

Six months later, she wrote me again. This time she sent a clock radio with my name on it, along with a note apologizing "for the misunderstanding." A few months after that I got an Easter card from "Your Biggest Fan!" Her next card had five exclamation points, which I took as a sign of escalating mania. I looked her up on the Internet to try to assess the threat. She was there. In fact, she had her own Web site, complete with a photograph of herself sitting at the computer. I'd never seen her before. She was a heavyset woman in her early forties with waist-length hair and short bangs. She didn't look crazy.

People who stumble across her site probably never guess. Jansen lists her many degrees (one in accounting, another in data processing, and yet another in something called Information Science) and promises to take care of just about any paperwork problem you might have. For reasonable rates, she'll draft your financial statements, process your Medicare claims, balance your books, or do your taxes. And although she doesn't say so, for no extra fee, she's also happy to include you in her delusions.

The site gave me the creeps, and I was tempted to call her and tell her to stop bothering me. I never did, though.

Copyright 2003. "Politicians, Partisans, and Parasites" excerpted by permission of Warner Books.

Shares