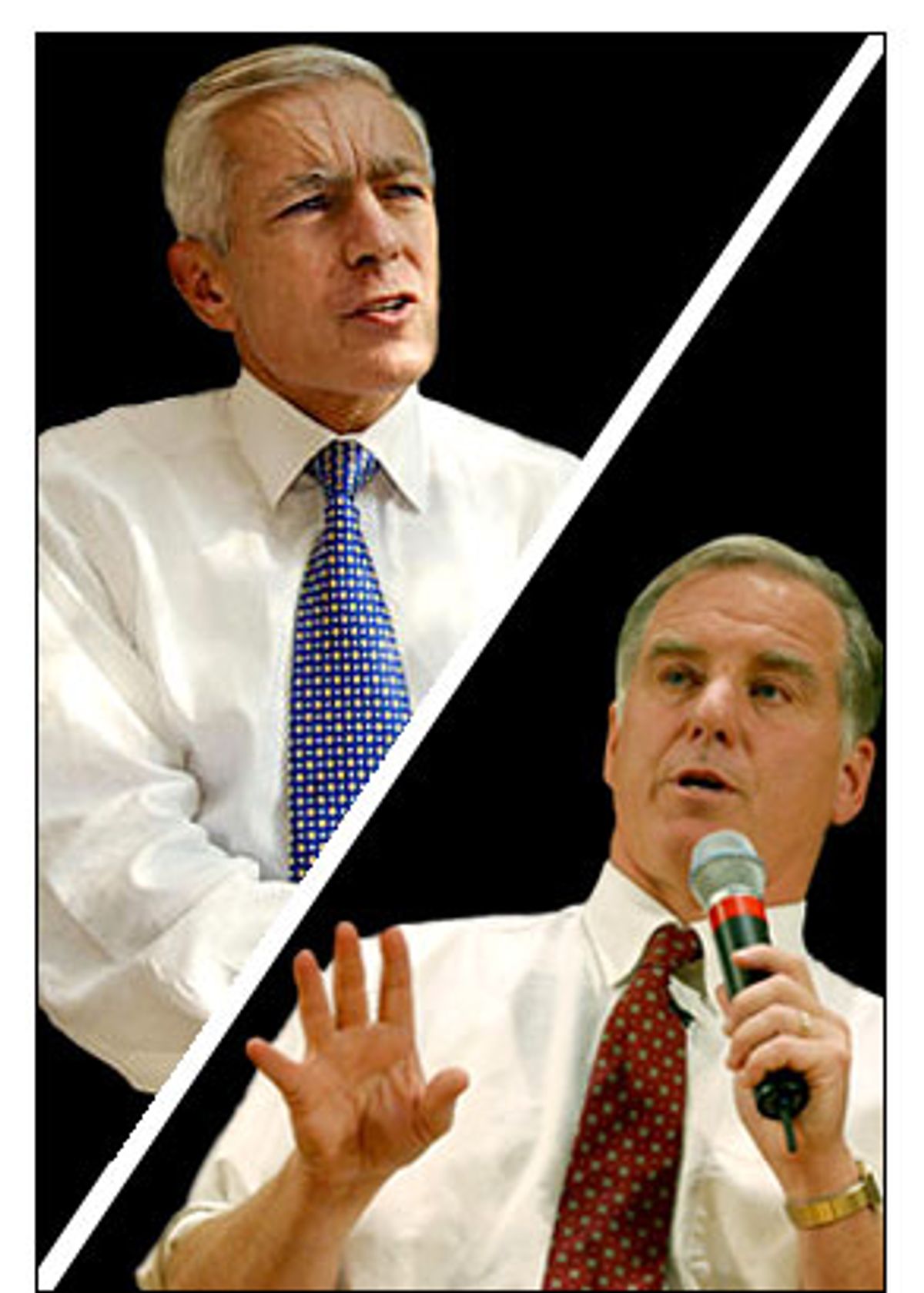

Former Vermont Gov. Howard Dean has spent the summer establishing himself as the unlikely Democratic front-runner, rallying the troops and raising enough money to hold off candidates once thought more formidable. But with the expected entry of retired four-star Gen. Wesley Clark into the race Wednesday, Dean may encounter his toughest competition thus far in the race for president.

As Dean has surged, high-ranking Democratic insiders have sometimes openly questioned whether he would flame out before the finish line, whether he had the experience and the broad political draw to beat well-financed incumbent George W. Bush. In Clark, they may have found their alternative.

Dean has fired hopes at the grass roots and attracted favorable media attention, and Bush today is more vulnerable than he's been since before the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks. But Bush is well funded and is likely to run a withering campaign, and skeptics doubt that an antiwar New England governor with no foreign policy experience will have what it takes to endure that. In Clark, they see someone with Dean's positives -- he's a straight-talking outsider who's been critical of Bush's handling of the war -- but who has Southern roots and strong credentials in foreign diplomacy and national security.

"I think part of what you're seeing is a split between the Democratic elites and Democratic base," says Eli Pariser, campaign director for the political advocacy group MoveOn.org. "Elites are less comfortable with the candidates we have now."

And specifically, less comfortable with Dean. "There are a nontrivial number of people in the party who say, 'Holy shit, how do you stop Dean? He's raised over $10 million in this quarter, and he'll probably hit the $15 million mark. How do you slow it?'" says a former White House official who spoke on condition of anonymity and who is not associated with any of the campaigns. "I think the traditional party operatives are afraid of the Dean campaign and don't understand it."

Like former President Bill Clinton, Clark is an Arkansas resident and Rhodes scholar. He is expected to launch his candidacy Wednesday in Little Rock, and has already assembled a team of advisors that includes many who worked for Clinton and Vice President Al Gore. Indeed, among many party leaders, there has been an almost wistful desire to see a Gore or a Clinton -- Bill or Hillary -- enter the race. But Gore insists he's out, Hillary has made no move to run, and Bill, having served two terms, can't run again. And so it is that many party leaders see Clark as a suitable alternative.

But Dean's supporters are known for their passion, which assures that Clark's announcement, and the inevitable Dean vs. Clark comparisons, are likely to be topics of intense interest among Democrats from the grass roots to the highest offices. Already, many are pining for a ticket that features Dean as the presidential candidate and Clark as his vice president.

But yesterday, Clark sounded like a man committed to seeking the highest office.

CNN reported that after meeting with Democratic officials in Little Rock, Clark met with reporters. The nation "is in significant difficulty, both at home and abroad," he told them. "I think it needs strong leadership and visionary leadership to take it forward. So that's what's drawn me to this prospective point right here."

Clearly Clark feels there's a hole in the Democratic field, which, with the exception of Dean, has been dominated by Beltway insiders like Sens. John Kerry of Massachusetts, John Edwards of North Carolina, Joe Lieberman of Connecticut, and by U.S. Rep. Dick Gephardt of Missouri. The retired NATO commander, former CNN analyst, and ardent Bush critic can position himself as the outsider -- the political novice -- yet also appeal to mainstream Democrats.

"He's more of a centrist Democrat," notes Larry Weatherford, political director for DraftClark2004.com. "I think he'll appeal to the same type of people who supported Clinton through the years."

That could be because he'll have the support of Clinton himself and his team of centrist alumnae, who may be watching the Dean ascent with concern. Clinton recently made the widely reported comment that his wife, Hillary, and Clark represent the "two stars" of the Democratic Party. "I think Bill Clinton is behind Clark," says Bill McCormack, Pacific Coast regional coordinator for DraftGore.com.

Clark's almost nonchalant suggestions recently that there will be financial backing for him if he decides to run -- he needs to raise tens of millions of dollars, and fast -- has led to speculation that he'll have open access to Clinton's rolodex.

Others put that sort of large-scale scheming, of the powers-that-be mapping out the nomination process, as beyond the grasp of party elites. "It's hard for me to believe it's superorchestrated," says one former Clinton White House official. "I'm always dubious of 'the party's' ability to shoot that straight. Remember, not that long ago, John Edwards was ordained the front-runner, and then he took a precipitous fall, and Dean began to rise."

Meanwhile, political veterans like Orin Kramer, an investment banker and key Democratic fundraiser in 2000, notes Clark has lost "valuable, valuable time" by playing the should-I-or-shouldn't-I waiting game for so long.

But perhaps Clark has the exquisite timing of a born star. By making his admittedly late announcement, he's joining the fray precisely as Bush crashes to his lowest post-9/11 standings in the polls. Just as the White House finds itself back on its heels for having its request of $87 billion to rebuild Iraq opposed by a vast majority of Americans, the arrival of a four-star, antiwar, telegenic general cannot be good news for Bush's reelection team.

Clark's entrance is unusually late in the primary process, especially for a political newcomer, and particularly since the upcoming contests are front-loaded on the calendar. To succeed he'll have to both prove himself as a born campaigner, and assemble a flawless campaign team nearly overnight.

He'll "have to hit the ground running, with the finest pair of sneakers you've ever seen," says Donna Brazile, who managed Gore's run for president.

"Given his stature and the press attention, he'll get a good first look" from voters, says another former presidential campaign manager, speaking on background. "But it's got to be a damn good first look."

Clark himself says he's not concerned. "The conversations I've had and the judgments I've made say it's not too late," he told CNN.

Clark will play up his nonpartisan past and present himself as a "what you see is what you get" kind of guy, who buys his suits off the rack at Nordstrom and watches movies at home on Saturday night. But skeptical voters may look to other facts: He was first in his class at West Point, a Vietnam veteran and supreme allied commander of NATO during the Kosovo military campaign. And almost every part of his critique of Bush's performance on Iraq has been proven right.

"He's a very bankable talent," says one former Pentagon colleague. "He's highly competent and a voracious reader who tackles issues with a lot of drive and determination."

On paper, the fact that Bush is sliding in the polls, while one of the Democratic candidates, Dean, is catching fire, should make most Democrats giddy over the coming prospects. Yet part of the constant chatter surrounding the Democratic lineup -- including Clark's late entrance -- springs from a nervousness over the Dean campaign, and whether the new front-runner will sweep up the nomination only to prove unelectable next November against a wartime president.

"Every time the bar has been set for Howard Dean he's met it and exceeded it," answers his campaign spokeswoman. "The way we'll beat George Bush is build the greatest grass-roots organization in history."

Others downplay the early hand-wringing. Rep. Anthony Weiner, D-N.Y., who has not committed to any of the current candidates, sees it as "an entirely predictable cycle" in which Democrats assess who's in the race, judge the field too weak, and wonder who might make a late entrance or be drafted to bolster the field. With Clark's entrance, Weiner says, "This is the field, nobody else is getting in, and we'll all rally around the nominee. And he'll be at 40 percent going into convention, he'll get a bump to 46 and then climb through the fall and the election will be [won by] two or three points."

Still, the chatter persists about who should really be in the race. "I don't subscribe that to nervousness," adds New Yorker Robert Zimmerman, a top Democratic fundraiser in 2000. "Speculating, fantasizing about candidates, it's part of the national pastime. It's as basic to American politics as direct mail."

But there seems to be something unique about the parlor games being played this campaign season. The fact that the election, at this point at least, suddenly looks like it could be a tossup has fueled the desire to bag a big, bankable Democratic name who wouldn't have merely 40 percent backing in polls before next summer's convention, but 47 percent, even 49 percent.

Thanks to a new strain of pragmatism inside the Democratic Party, electability has become the mantra as an influential bloc of officials, activists and donors remain intent on using the election not to win the heart of the party, but to beat Bush. Issues have in many ways taken a back seat so far. Yes, issues get debated on TV, and the details of Iraq, Medicare plans and deficit spending are explored, but within the party there seems to be a simple, pervasive desire for a candidate who has the greatest chance of winning. Compare that to the 1992 race when it took Bill Clinton months to convince party activists not only that he could beat Bush, but that his centrist, third-way approach did not pose a fundamental threat to the party's principles.

"We're not going through therapy to find our soul -- we're beyond that," says Zimmerman. "We're as focused [on winning] today as Republicans were in 2000. We've seen the reckless incompetence of this administration, both with the economy and in Iraq."

Even the split over Dean is mostly about electability, not policy positions.

It's that laserlike motivation that's led some to keep searching for just the right candidate. And even with the entrance of Clark, there are some who feel that the past holds the key to the future.

"It's all about winning," says Monica Friedlander with DraftGore.com. "There's never been a more desperate time when Democrats needed to field a person with the best chance to win. Gore's absolutely that person. I don't think somebody like Dean is seen by the voters as somebody who can win the White House, compared to Al Gore who has a quarter of a century of public service behind him."

According to a Zogby poll commissioned by DraftGore2004.com, Gore and Bush today stand in a statistical dead heat, with Bush pulling 48 percent and Gore 46. Gore is the only Democratic candidate who polls that well against Bush, whose job approval ratings have sunk to pre-9/11 levels around 52 percent, according to a USA Today poll. Bush's grades for handling the economy continue to sink even further.

By comparison, at this point in 1991, Bush's father enjoyed approval rating of 64 percent, according to a Wall Street Journal poll published in September of that year. Back then, Democrats were nervous that without household names like Cuomo, or Bradley, or Gephardt, the party didn't stand a chance against the president coming off a Gulf War victory.

When Democratic voters were recently asked by CBS News which candidate they wished was in the race, Gore easily finished first with 19 percent. He was followed by Hillary Clinton at 6 percent, Bill Clinton with 2 percent, and Clark with 2 percent.

"I get daily phone calls from Democratic activists, Democratic leaders and major contributors around the country hoping and trying to encourage Al Gore to run for the presidency," says Zimmerman. "I'm astounded at who's calling."

"I think he'd be welcomed back in the race. The question is: Does he want to run?" asks Rep. Carolyn Maloney, D-N.Y.

In a recent speech critical of Bush, Gore stressed that he would not run. The vice president's spokeswoman insists that decision hasn't changed: "He has been very clear he's not a candidate for president in 2004."

One party insider suggests Gore's losing performance in 2000 "is still too much of a liability to overcome. I think people would rather take a shot with an unknown like Clark."

Meanwhile, New York Sen. Hillary Clinton, who repeatedly told voters in 2000 she would not run for president in 2004, has not made any move toward jumping into the race. The conventional wisdom is that if Bush is reelected, Clinton is preparing herself for a run in 2008.

"She clearly has the most star power among Democrats," says Dante Scala, professor of politics at St. Anselm College in Manchester, N.H. "New Hampshire activists are just waiting for her to give the word."

The what-if jockeying is all taking place against the backdrop of Dean's rise in the polls, and his runaway success with fundraising, fueled in part by unprecedented online donations. But the fear among some analysts and activists is that he's staked out too many liberal positions that won't translate well in the general election.

In other words, Clark never signed a bill into law allowing civil unions for same-sex couples. As governor of Vermont, Dean did.

"The conventional wisdom settling in is that he's unelectable," says Weiner. "But he's trying to deal with that. And I'm hearing much more buzz in the opposite direction; mainstream institutional groups don't think the Dean thing is going away, and they're trying to figure out how he can win with him."

"Is there concern about his electability? Yes. Should there be concern? Not necessarily," says pollster John Zogby. "Because 1) boy, does he know how to run a good campaign. He's far beyond expectations. And 2) he's not George McGovern. He can easily be moved to the center where he's spent most of his political career."

"The level of panic about Dean is not as high as it was because people are impressed by money he's raised and the energy of the campaign," adds Ruy Teixeira, a senior fellow at the Century Foundation, and coauthor of "The Emerging Democratic Majority." "As Bush's numbers go down and Democratic chances improve, there's the realization that a pretty good campaign can beat this guy."

This story has been corrected since it was originally published.

Shares