Can a movie seem like a disaster and still convince you you're seeing something bold and new? Olivier Assayas' unclassifiable "demonlover" (calling it a "cyberthriller" reeks of a determination to shoehorn it into a category in which it will not fit) is a mixture of folly and brilliance, often at the same time. The movie feels like a shambles, and yet it's a stunning example of a director in complete control of his material. Distilled to their essence, the ideas Assayas is putting forth here seem silly and even alarmist. At times, "demonlover" plays like the most paranoid fantasies of anti-globalization and anti-porn activists. But Assayas has locked on to some ugly truths about corporate and private life and about our relation to technology right now, and what he's saying is no more dismissible because it's obvious.

So much twaddle is written about the "ideas" in movies and books that we fail to recognize that sometimes the force with which something is expressed counts for as much as -- or more than -- its content. "Demonlover" is cold and feverish, sadistic and appalled by the sadism it shows us, narratively opaque and thematically lucid. It's a consistently exciting piece of moviemaking, but it's not a pleasant experience; it's one of the few recent movies that have the power to leave you genuinely shaken up.

That may sound like fence straddling, but the truth is that neither the praise nor the derision that "demonlover" inspires has grasped its contradictions. The film got a murderous reception at the 2002 Cannes Film Festival (it has since been cut by 12 minutes) and then from French critics, and it bombed when it was released in that country. Now the movie's American supporters seem to be gearing up for its release here, perhaps relishing a chance to give it back to their Gallic counterparts who have always delighted in ridiculing Americans for the homegrown treasures we have trashed.

The emerging critical line on "demonlover" seems to be that all the critics who have complained about the incoherence of the movie's storyline have missed the point. Assayas, his supporters argue, is attempting to capture the nonlinear experience of the Internet or of moviewatching in the era of DVDs, when you can look at parts of a movie in any order you wish. Assayas has spouted his fair share of nonsense seconding that opinion. In interviews like the one in Cinema Scope, reprinted in the movie's production notes, Assayas says of the film's detractors that what they call coherence is actually "some kind of conventional framework to express the conventional emotions of supposedly nonconventional characters who actually end up being more conventional than conventional."

He adds, "People have this very stiff notion of what cinema is and what cinema should be, and then try to apply rules that are old rules, rules from another time ... Then you have to shake up the whole thing, and believe that you can create new connections, try in your own modest way to open new doors for what cinema can be." He says that the movie's characters start out "in a classic genre situation" but end up "on their own ... Instead of being driven by the manipulative conventions of safe storytelling, they are manipulated by their own subconscious, by their own inner logic, or absence of logic."

Who can blame a talented young filmmaker (and Assayas is the most talented French filmmaker of his generation) for not wanting to make the same genre movie that's already been made a thousand times? Still, this is nonsense. Assayas' characters are not "on their own." Their choices and their fate have not been decided by the whims of a million Web surfers or DVD viewers. They have been decided by Assayas himself. And if he claims that psychology and motivation are nothing more than tyrannies of outmoded storytelling, then he is not commenting on the nonlinear experience of narrative in new technology but merely replicating it. Most of the plots of the big Hollywood blockbusters don't make any sense, and nobody is going to give them any credit for pioneering daring new avenues of cinema. It's not timidity that angers audiences or critics when they play by the rules a filmmaker sets up (for its first hour, "demonlover" has a meticulously constructed narrative) and then, without being prepared for a switch, find that the director has changed the rules on them in the middle of the game.

If there's any storytelling model for "demonlover," it may be Howard Hawks' film of "The Big Sleep," whose insanely labyrinthine plot becomes less important than the feeling of a miasma of corruption in which connections are too dense and deep to ever be fully understood. "demonlover" zooms willfully off the narrative rails about halfway through, and trying to make sense of the plot later only yields explanations that cancel each other out. Yet I'm not sure the movie would be as powerful if it didn't take that leap into incoherence.

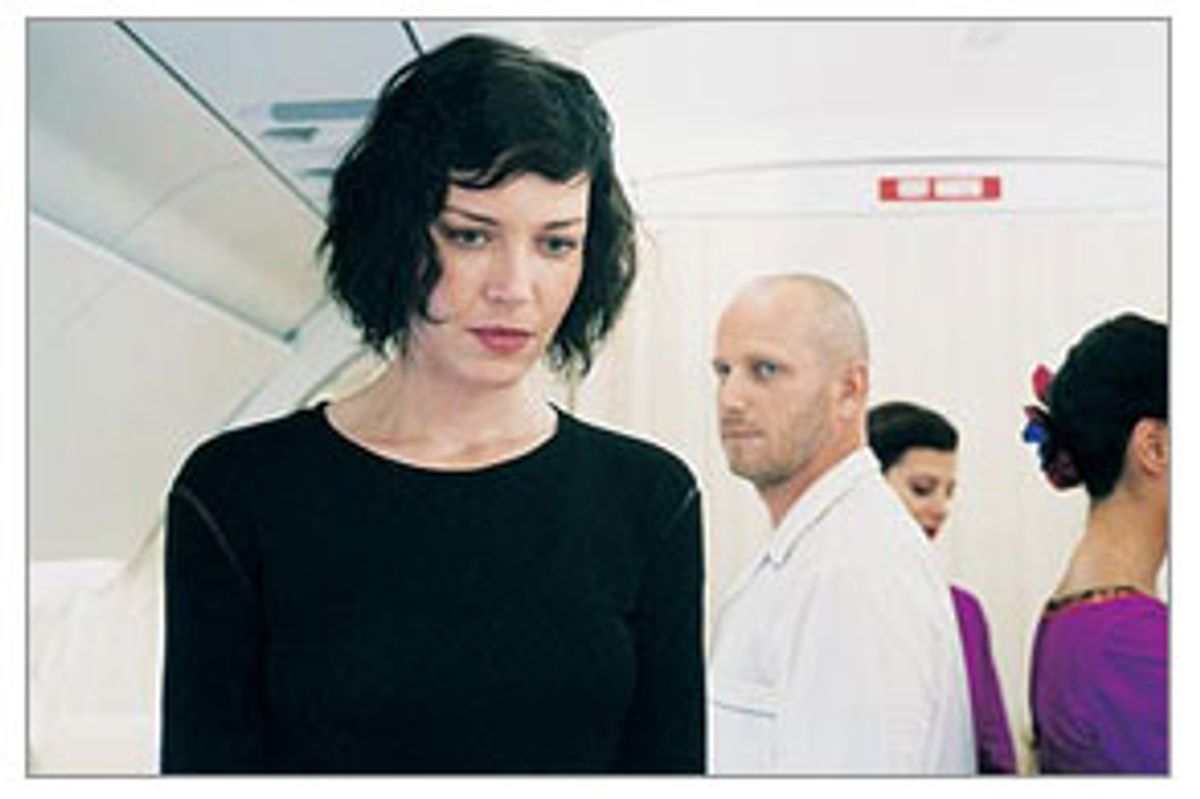

To borrow one of those classic storytelling descriptions Assayas disdains, nothing and no one are as they seem. The film is about two companies battling for the distribution rights of a Japanese anime production house that's about to revolutionize the market with the introduction of 3-D porn. Diane (Connie Nielsen) represents an international acquisitions firm working to get those rights and sell them to an American company called Demonlover. But she's actually a spy for Demonlover's main competitor, Mangatronics, and any questions about how far she'll go are answered in the opening scene, when she arranges to take over from Karen (Dominique Reymond), the woman handling the negotiations, by injecting Haldol into Karen's Evian and having her kidnapped by two thugs who leave her in the trunk of her car.

Conniving her way into the catbird seat, Diane finds herself dealing with the attentions of her coworker Hervé (Charles Berling), who suspects she may have had something to do with Karen's assault but is just as happy to have Karen gone, and the suspicions and resentment of Karen's assistant Elise (Chloë Sevigny).

Part of the icy humor of "demonlover" is that Diane appears to be behind the game from the start. Assayas is out to take the measure here of a borderless, transient world in which the Internet, globalization, and corporate mergers and takeovers have obliterated any sense of continuity or personal loyalty. If the first two "Godfather" movies were the ultimate statement about crime as a logical extension of the corporate ethic, "demonlover" takes that logic to the next step. A mobster who betrays his "family" for the sake of some crime boss's grab for power is a piker compared to the multiple machinations of the characters in "demonlover." In one sense, the movie can't help but devolve into incoherence because it's dealing with a world where people's motivations are fractured, always up for sale.

"Demonlover" trumps the worst fantasies you can come up with about the moral rottenness of big business. When Diane dopes and kidnaps her competitor, she's simply doing business as usual. She's no colder or more calculating than anything going on around her. When Diane meets with the representatives of Demonlover and confronts them with the fact that their Web site is the entry to a secret site called Hell Fire Club, the company's executive, Elaine (Gina Gershon, playing the businesswoman as jaded rock star), explains, as blasé as she can be, "it's an interactive torture site," and her partner proudly adds, "the best, I'd say." Torture has become simply a new business venture, a niche to be filled by corporations determined not to be left behind in anything.

When Diane accesses the site herself, she's greeted by movies of models bound and gagged and shackled to electrified bed frames, or encased inside rubber catsuits and submerged in water. Accompanying the images is the invitation: "This is Zora. How would you like to torture her?" Users are invited to submit their fantasies and watch women dressed like Wonder Woman or Emma Peel (in other words, the predominant pop-culture icons of strong women) tortured to their liking. Your pleasure is only a few credit card numbers away. If you're as squeamish about torture scenes as I am, you should know that what Diane sees on Hell Fire Club is not explicit but rather rapidly edited, often in close-ups that blur the specifics of the action, and more suggested than lingered on. The scenes are not pleasant, but they're done with as much discretion as possible.

"I think that if most guys in America," Lester Bangs wrote in 1980, "could somehow get their fave-rave poster girl in bed and have total license to do whatever they wanted with this legendary body for one afternoon, at least 75 percent of the guys in the country would elect to beat her up. She may be up there all high and mighty on TV, but everybody knows that underneath all that fashion plating she's just a piece of meat like all the rest of them." Even allowing for Bangs' consciously overstating the case, there's too much Susan Brownmiller hoo-ha in that passage for my taste.

But the truth in his words is reflected here in the way Assayas has keyed in to the essential reality of both the Internet and the present state of pornography: Every interest is catered to, from the most benign to the most repulsive. Assayas doesn't make it easy to agree with him, because he resurrects the clichés about porn as the white slave trade, the rumors of snuff movies, and the like. But he's not wrong in positing that the freedom and range of the Internet, coupled with the corporate determination to profit from any desire and keep the dollars coming by finding a way to go further, is heading toward some Sadean event horizon.

In his book "An Erotic Beyond: Sade," Octavio Paz said that in vilifying the state and glorifying the murderer, Sade aimed to replace public crime with private crime. "Demonlover" is an essay on how public crime (actually crime committed in secret by public companies) makes private crime possible. Consumers here are not the innocent marks of money-mad conglomerates; they're accomplices. Laying this stuff out risks making Assayas sound like the avant-garde William Bennett. But you don't have to be a Puritan or a would-be censor to be appalled at spam advertising "Russian Rape Sites" or the sheer brutishness flourishing in some corners of porn movies. And the cool ambivalence of "demonlover" is not the mark of a proselytizer but of a rigorous logician.

Assayas seems to agree with Sade that the logical endpoint of the erotic impulse is the desire to annihilate. He has coupled that here with the logical endpoint of capitalism -- the desire to annihilate all competition. "I say let's do it," Gershon's Elaine says when she outlines a plan for obliterating Demonlover's competitor, and the dirty curl of a smile on her face is the only pleasure she shows in the entire movie.

"Demonlover" flirts with clichés about media desensitization. In the opening scene, airplane passengers take no notice of TV monitors playing action-movie footage of explosions and burning bodies. No image, no matter how vile, elicits much of a reaction from anyone here -- not anime rape scenes or the schoolgirl porn Diane flips on in a Tokyo hotel room. Whatever Diane watches, her face registers nothing more than a distant, calculated interest in a new product. But what would seem like finger-wagging from some media watchdog means something quite different coming from a filmmaker of Assayas' caliber. This is a nightmare world for Assayas -- for any filmmaker concerned with the future of movies -- because it's a world in which people are no longer affected by images, in which images have been emptied of any meaning beyond their surface ability to please or excite.

Assayas is so disciplined about maintaining a distanced, observant tone that at times "demonlover" risks looking as disaffected as the world it depicts. But the images he and cinematographer Denis Lenoir put on-screen are never disposable commodities. Even with the coolness of his approach, the images carry weight and meaning. "Demonlover" takes place almost entirely in the world of the temporary: in planes, hotel rooms, offices, restaurants, night clubs. Lenoir has shot the movie in CinemaScope to emphasize the white sterility of those surroundings. (When we see colored neon refracted through raindrops on a windshield, the image seems to have strayed in from a place where warmth still exists.) The demarcations between one country and another, between day and night, between work and private life, have given way to an undefined, enveloping space -- the amorphous, consuming marketplace. Identity is just as impermanent: "Diane" is a wholly made-up persona -- we never discover exactly who this woman is.

The movie itself might dissolve if Connie Nielsen weren't there to hold it together. Assayas recognizes that Nielsen is one of the movies' natural goddesses; her height and carriage and porcelain beauty say that the screen is hers to take by right. Nielsen burrows beneath Diane's ice-queen surface as the events of the movie and the hidden motivations of the other characters prove her to be a few crucial steps behind. She's in an impossible situation here, playing a character whose survival depends on keeping a placid surface while suggesting the cracks in that surface that give us a whiff of the raw fear underneath. And, playing a character whose motivations and actions are increasingly and purposefully not spelled out, Nielsen has to find a coherence where none exists. That she does is a testament to her talent. Nielsen has the most direct, harrowing moment in the movie, our final glimpse of Diane, staring straight into the camera at us, accusing and fearful. It's a moment that aims to abolish the distance between actor and audience, and the look on Nielsen's face is one that may rob you of sleep.

Nielsen told the Village Voice, "It was a challenge to try and make a weird sort of sense from the complete illogic of [Diane's] choices, but if you start asking yourself why and how and what all the time, the whole thing starts to disintegrate." Some sort of sense does emerge from Diane's choices. In a way, she's the movie's ultimate corporate player, the one who grasps the deepest, most unapologetic urges of corporate life and surrenders herself to them. She's the movie's "O" learning obedience at the villa of the Fortune 500. Tempting a metaphor as that is, it doesn't make the movie any less of a cheat, which always has to be the judgment of a movie where the thematic meanings are not expressed in terms of the plot and characters it sets up. But it would be equally wrong to say that Assayas is lying for insisting that "demonlover" proceeds according to an alternative logic.

Where "demonlover" leaves him in terms of his own career is almost impossible to say. Assayas is now working on his next movie, starring his ex-wife and "Irma Vep" star Maggie Cheung. If it turns out to be a more "conventional" narrative than "demonlover," it's almost a given that this film's admirers will talk disappointedly of his retreat. What's most disturbing about Assayas' statements about how narrative moviemaking is played out is that he's selling his own talent short, denying what he's brought to the form. "Irma Vep" is one of the miracles of modern movies, maybe the most joyous, inclusive celebration of moviemaking that movies have given us, and an abiding statement of faith in the potential that remains in the art form.

And the film that followed, "Late August, Early September," is more accurate about the aspirations of people in their 30s and early 40s who are drawn to the arts than any other movie I know. It's nonsense for Assayas to say, "To make movies in a world where people don't have cellphones, are not exposed to modern images ... that is exactly what movies should not be," because that's a perfect description of the film he made before "demonlover," the 19th century period piece "Les Destinées."

"Les Destinées" was exactly what Assayas should not have been doing (I made it about a third of the way through its three-hour length), and part of the problem was that a director as attuned to the contemporary world as Assayas is, was working with material that cut him off from his strengths. But to say that only contemporary art can have any relevance, or that classic forms, no matter how intelligently and probingly done, are reactionary, is hideously reductive. "Demonlover" demonstrates equally the traps and the breakthroughs that can come from being so up-to-the-minute.

Assayas is clearly concerned with how new technology is shaping our lives and our characters; he's concerned with how it's changing our experience of art, and how, in conjunction with big business, it's changing our notions of morality. Is morality even possible, he seems to be asking, in a world where every desire can be privately fulfilled? (It's ironic that several reviews of "demonlover" have compared it to William Gibson's beautiful novel "Pattern Recognition," which sees much more hope and features the writer's most coherent and satisfying plot.) Assayas is right that there are new ways to make movies, but all he seems to find in the new technology is depersonalization and brutality. In some ways, "demonlover" is the first Luddite film of tomorrow.

For all its faults, it's also a hard, unsparing look at where we are right now, at how work has taken over every aspect of our lives, about how all art, feeling, relationships and morality stand on the brink of being commodified, and about how we are both seduced and repulsed by those possibilities. You can see all the structural and psychological woolliness in "demonlover," you can be exasperated by it or turned off by it, and still feel it's one of the most vital pieces of moviemaking in recent memory, still feel that it tells you more about the tenor of the moment -- maybe more than we're ready to acknowledge -- than any other recent film. It's a movie worth arguing about.

Shares