"[It has] a perfect marketing plan, a product you can't not buy, assuming you can afford it and you find out about it in time." So wrote Josh Goldfein, a New York lawyer and writer, in the New York Times Magazine this past July. Goldfein wasn't referencing TiVo or the Segway scooter, but the fairly new and rapidly growing industry of private cord blood banks, which profess to offer a sort of biological insurance for the newly born via a deceptively simple idea: store the blood from your baby's umbilical cord (rich with stem cells) and you may have the material you need to cure his or her future diseases. And although Goldfein is admittedly unimpressed by the pressures these private companies put on expectant parents -- "I think [these companies'] entire marketing strategy is based on fear," he says -- in the end, he did bank his newborn son's blood.

With 4 million births in the U.S. each year, cord-blood banking is becoming a big business, with dozens of private banks in the U.S. alone, and more on the way. ViaCord, one of the country's largest private cord-blood banks, sends brochures to Ob/Gyn offices around the country, and takes out expensive glossy advertisements in magazines like Fit Pregnancy. So does competitor Cord Blood Registry (CBR), which has also run television spots on new-mommy-friendly shows such as TLC' s "A Baby Story." CBR even advertises the fact that well-known pediatrician Dr. Robert Sears has stored his children's cord blood with the company, and last month, it hired celebrity reporter and TV personality Leeza Gibbons as its new spokesperson.

All this fancy advertising is indicative of a fancy price, of course. The cost of the initial processing of cord-blood can run up to $1,500, and that's not all: with an added fee of approximately $90 per year for storage, just 10 years' worth of maintaining a baby's cord blood can add another $1,000 to the bill. But out of optimism, paranoia or a sense of duty, thousands of anxious parents-to-be are forking over their cash to such privately owned and run cord-blood banks. And it's the steep cost -- coupled with the very remote probability that the cord blood will ever be used by the family that banks it -- that has some critics shaking their heads.

The American Academy of Pediatrics, for one, released a statement in 1999 that cast a dubious light on the for-profit industry. Given the current technology (which does not support a particularly wide range of uses for cord blood), the academy wrote: "... private storage of cord blood as 'biological insurance' is unwise." The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists' position, outlined in 1997, stated that although cord blood transplants "seem very encouraging," "until there is a fuller understanding of all of these issues, we must proceed with considerable circumspection. Parents should not be sold this service without a realistic assessment of their likely return on their investment."

"It's about people's tolerance for risk," says Goldfein. "It's insurance. It's preparing yourself for the risk of a bad thing happening. I think the biggest question mark about the whole [industry] is that a lot of the medical benefits you can derive from cord blood don't yet exist, and you're taking a leap of faith that the cells you save now will be useful in the future."

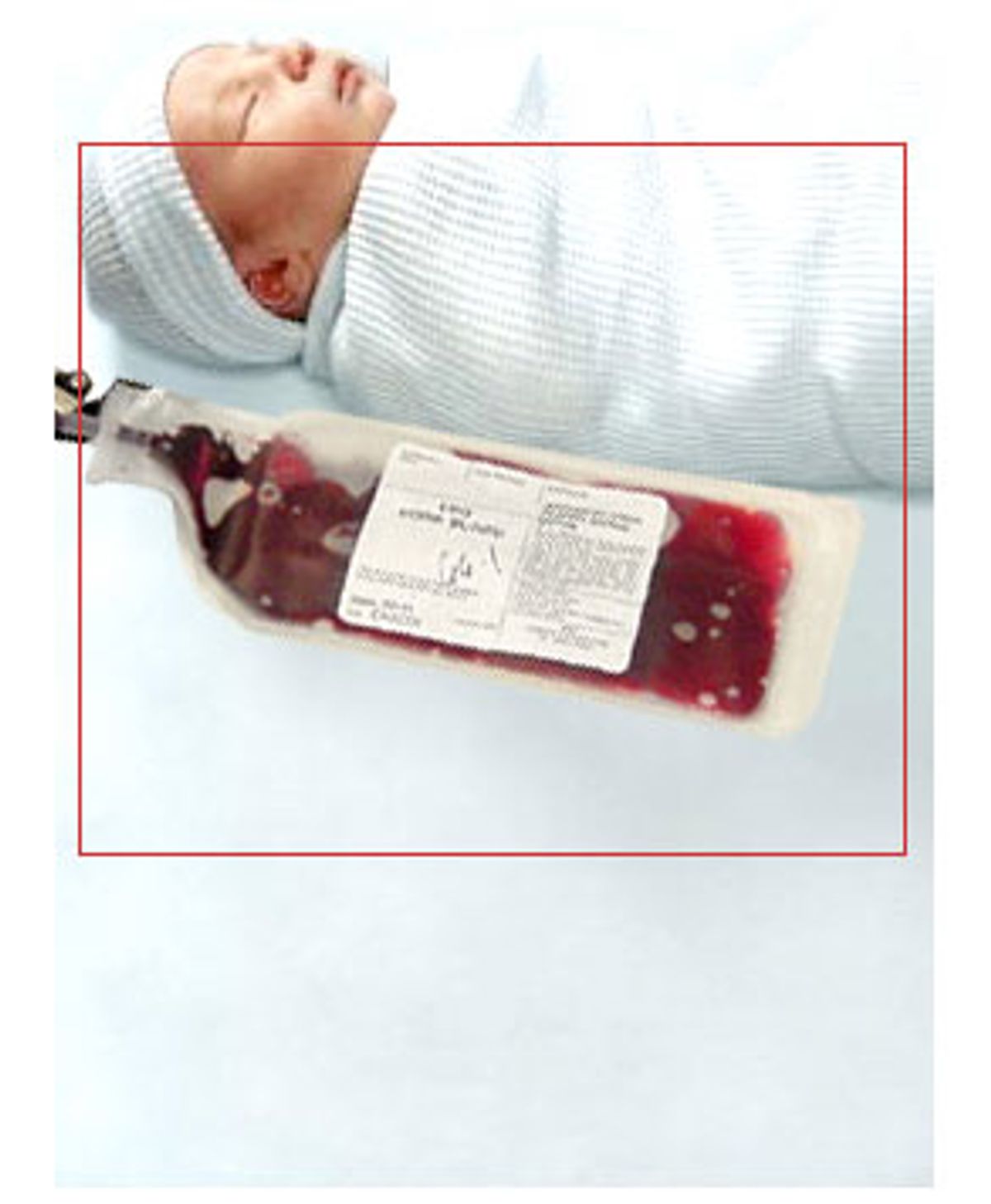

But what are those medical benefits, actually? First off, it's important to clarify exactly what cord blood is, which is the blood that is found in a baby's umbilical cord and placenta after the cord is cut following birth. That blood is full of stem cells, which are essentially the building blocks of a body's blood and immune systems, and researchers have used such stem cells to regenerate these systems in sick patients. Indeed, some people have been successfully treated with stem cells for a myriad of conditions, including leukemia, genetic metabolic diseases, immune deficiency diseases and blood disorders such as sickle cell anemia. Some researchers are hopeful that technology will advance to the point where cord-blood stem cells will be able to treat all sorts of different types of cancers, as well as diseases like Alzheimer's and diabetes. Maybe one day, stem cells will even be used to grow new organs.

But that hasn't happened yet, and there's no assurance that it ever will. "Currently, cord blood transplants are performed on patients who have a blood cancer or genetic disorder where the patient hasn't responded to traditional therapies," says Dr. Liana Harvath, deputy director of the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute's division of blood diseases and resources. "And it's extraordinarily rare that a cord blood transplant would occur in which a newborn's cord blood is given back to the same donor."

This is because the very blood that was saved could be the same blood that caused the disease in the first place. "Most of the kids who need transplants that could involve the use of cord blood will have a genetic disease in which you couldn't use their own blood because the kids might just get the same disease [all over again]," explains Dr. Cladd Stevens, medical director of the cord blood program at the New York Blood Center, the largest public cord-blood storage center in the country. "Take an instance in which a child develops leukemia later in life. There is good evidence that these kids have the leukemic cell in their blood at birth."

Rather than paying thousands of dollars to store cord blood for a child who will probably never use it, Stevens and other public-health advocates recommend that new parents donate their child's cord blood to a public bank, where it can be used by anyone who needs it (much like a bone marrow donor program). The New York Blood Center, for one, has collected cord blood from almost 22,000 babies since 1993 and has given cord blood to more than 1,400 patients around the world. But the problem that the public banks encounter is their accessibility to potential donors, who must be geographically close to the banks they want to donate to. "We've gotten calls from mothers saying they want to donate their child's cord blood but there's not a program near their hospital," says Harvath. "Not all regions of the country have public banks yet."

This was the problem for Christine D'Amico, 38, a life transition coach and author of "The Pregnant Woman's Companion." D'Amico and her husband wanted to donate their second child's cord blood to a public registry three years ago but were dismayed to find there was not one close enough to their San Diego home. So with their third child, born a month ago, they chose a private bank. "My opinion is that donating [to a public bank] is probably better because someone can get access to it immediately and use it," says D'Amico. "And the private banks are expensive. But I also thought, who knows what amazing things doctors will be able to do in the next 20 years with this really valuable body fluid, and wouldn't we be pissed off at ourselves if we didn't take advantage of it?"

Expectant parents who are considering cord blood banking and don't know whether to chose a public or private bank should take into account their finances, their family medical history, and whether or not a public cord blood bank is nearby. If you are considering a private bank, Dr. Harvath advises asking company representatives how many units of cord blood in their bank have been successfully used in transplantation (of 50,000 units at CBR, for example, 27 have been used in transplantation, although no figure is available as to the success of those procedures). She also recommends asking whether a bank has been accredited by a professional organization such as the American Association of Blood Banks. "My message has always been for consumers to be aware and weigh the facts," she says. "It's like any other kind of emerging technology."

Fran Verter, a NASA employee who lives in Maryland and is the co-creator of the Web site ParentsGuideCordblood.com, became interested in cord blood after her daughter Shai developed leukemia (Shai died in 1997 at the age of 4 and a half despite a bone marrow transplant). It was her daughter's diagnosis -- and Verter's need to educate herself about leukemia and its possible treatments -- that introduced her to what she calls the "complex subject" of cord blood. Shocked that there were so few resources available to parents who wanted to educate themselves about cord blood -- Verter says that even her doctors knew little about it -- she began to research it herself, and the idea for a Web site soon followed.

Verter's site does not preach the value of private banks over public, or vice versa, although she's a front-row witness to the mutual skepticism that private and public banks have toward each other. "The private banks exaggerate a lot in their literature, making it sound as if you can use a baby's cord blood in case the baby gets cancer, which really isn't true," she says. "And the public banks like to emphasize the unlikelihood that cord blood will be used from the child from which it was harvested. There's a certain amount of propaganda on both sides."

With no federal regulations on private cord blood banks, and so little unbiased information available to the public, it's up to doctors to wade through the hype and help expectant parents make informed decisions. Dr. Gary Goldberg, an obstetrician/gynecologist at New York Presbyterian Hospital Cornell Medical Center, says he is a "big advocate" of cord blood banking, and usually broaches the topic with his patients at around the 32-week mark (the same time he brings up finding a pediatrician). "The information we have suggests that the potential for the use of cord blood in correcting problems like diabetes and Parkinson's and spinal cord injuries is only going to grow. The research is still in its infancy but it's really exciting."

Goldberg displays brochures from private cord blood banks in his waiting room. As for some companies' marketing tactics and high costs, he is sanguine. "I think in a capitalistic society it's unavoidable," he says. "I think that these companies call in the spin doctors and make themselves and their products sound like the best thing since scrambled eggs. [With regard to cost], the way I describe it to my patients is that the two leading companies are the most expensive because they have to fund their research. My concern about [the smaller and cheaper] companies is, will they be around in the long term and if not, what will happen to the blood that they had?"

Some new mothers have extremely personal -- and pressing -- reasons for paying the high costs associated with private banks like CBR and ViaCord. Take Amie Gbelawoe, 27, an actress in Los Angeles, who gave birth to a daughter, Luna, in early May, and banked her daughter's cord blood with one of the large private banks. "I first learned about cord-blood banking through reading pamphlets in my doctor's office and there was no doubt in my mind: I was absolutely going to do it," says Gbelawoe. "It seemed like an amazing opportunity, and I'd rather be safe than sorry." Gbelawoe decided to store Luna's cord blood because her husband Ramsey suffers from sickle-cell anemia. Although their daughter only carries the sickle-cell trait, theoretically, her blood could be used to help treat her father's disease someday.

Few dispute that, given new and emerging technologies, cord blood is a potentially life-saving resource for families like the Gbelawoes. Dr. Stevens of the New York Blood Center says that she thinks that cord blood has a big future. But she and others express concern that some cord blood companies are diverting potential public donations to their own private freezers, where the blood will be of no use to the public and of unlikely use to the depositor.

"The major part of [these companies'] business is speculation," says Stevens. "They have big campaigns, and of course they play on people's emotions: 'There's a one-time chance to do this.' It has a pretty strong emotional appeal. But what if a family finds that they need their cord blood but the bank can't find it? Or what if the bag of blood broke? Or what if the unit of blood is too small for a transplant? In my mind, it's kind of a crazy business."

Sara Brown, 31, a public-school teacher in the San Francisco Bay Area who is expecting her first child in December, was turned off by the aggressive marketing tactics used by the private banks. "I saw an ad in a baby magazine that made it sound like you'd be a fool or a bad parent if you didn't do this. It just seems like these companies are taking advantage of people in a vulnerable position. I have faith that science will have other treatments and cures for the sort of diseases that cord blood could possibly be useful for."

Although some professionals and parents suspect that companies like ViaCord and CBR are simply preying on the fears and anxieties of expectant parents, the companies themselves are, of course, inclined to disagree. "Unfortunately, you have to address the subject of health even before a baby is born," says Stephen Grant, vice president of communications and cofounder of CBR, which currently stores about 50,000 samples. "Twenty-eight percent of our customers are healthcare professionals [themselves]. It may not be a necessary [procedure], but that doesn't mean it isn't wise or prudent."

Wise or not, the cord-blood banking industry has yet to be regulated by the FDA, which considers cord blood use experimental. "This is a whole new field and it's taken a long time for the FDA to figure out what measures they need to assess in terms of quality," says Dr. Stevens of the New York Blood Center. The FDA hopes to start regulating cord blood banks next year, and there is a bill (HR2852) pending in Congress that, if passed, would create a national network of public cord blood banks. "If it passes, it will change the landscape," says Fran Verter. "It would make public banking a lot more accessible. Right now the public banks have about 58,000 donations and this legislation proposes to create an inventory of 150,000. I have my fingers and my toes crossed."

Shares