Even as Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld made headlines this week by announcing that up to 20,000 fresh troops may be called to Iraq, President Bush and members of the congressional leadership were quietly abandoning a plan to protect troop-transport airliners from missile attack by terrorists or Saddam loyalists.

The measure, first advanced by the Pentagon, would have begun an ambitious program to equip the commercial airliners that are used for troop transport with advanced technology to protect them from the shoulder-fired missiles. Confused by disarray in the administration's plans to protect airliners from missile attack, the House of Representatives slashed the original $25 million request to $3 million. Congressional officials say the Bush administration did nothing to win approval of the full measure -- despite recent missile attacks on U.S. military craft flying near the Baghdad airport.

The outcome shocked many in the Defense Department and, critics said, it clearly could leave troops vulnerable. "I am appalled," said one Defense Department official who asked to remain anonymous. "We are setting ourselves up for a fall. We are paying lip-service to force protection and instead are digging a deeper hole in which to bury our head."

The $25 million measure was approved by the U.S. Senate, but slashed to $3 million in the powerful House Appropriations Committee, chaired by U.S. Rep. C.W. Bill Young, a Florida Republican. The lower sum, part of the proposed $400 billion defense budget for 2004, was approved in negotiations between the two chambers and is all but certain to be in the budget sent for approval to the president.

No president in recent memory has been a fiercer ally of men and women in uniform. "We will not cut corners when it comes to the defense of our great land," Bush said last year. Even Ronald Reagan, one of the most forceful proponents of a strong military ever to inhabit the White House, never donned a flight suit and flew onto the deck of an aircraft carrier aboard a Navy plane. But this week, officials said, the Bush administration offered no support to protect the troop-transport planes.

"The administration never made the case for why it needed the money," said John Scofield, a spokesman for the House Appropriations Committee. "It was never clear what they were going to do with the money." An aide to a Republican senator, who asked to remain anonymous, said the full funding would have been approved if Bush had pressed for it. "If the president says that something is important, he will get the funding from this Congress," the aide said. "All he has to do is ask."

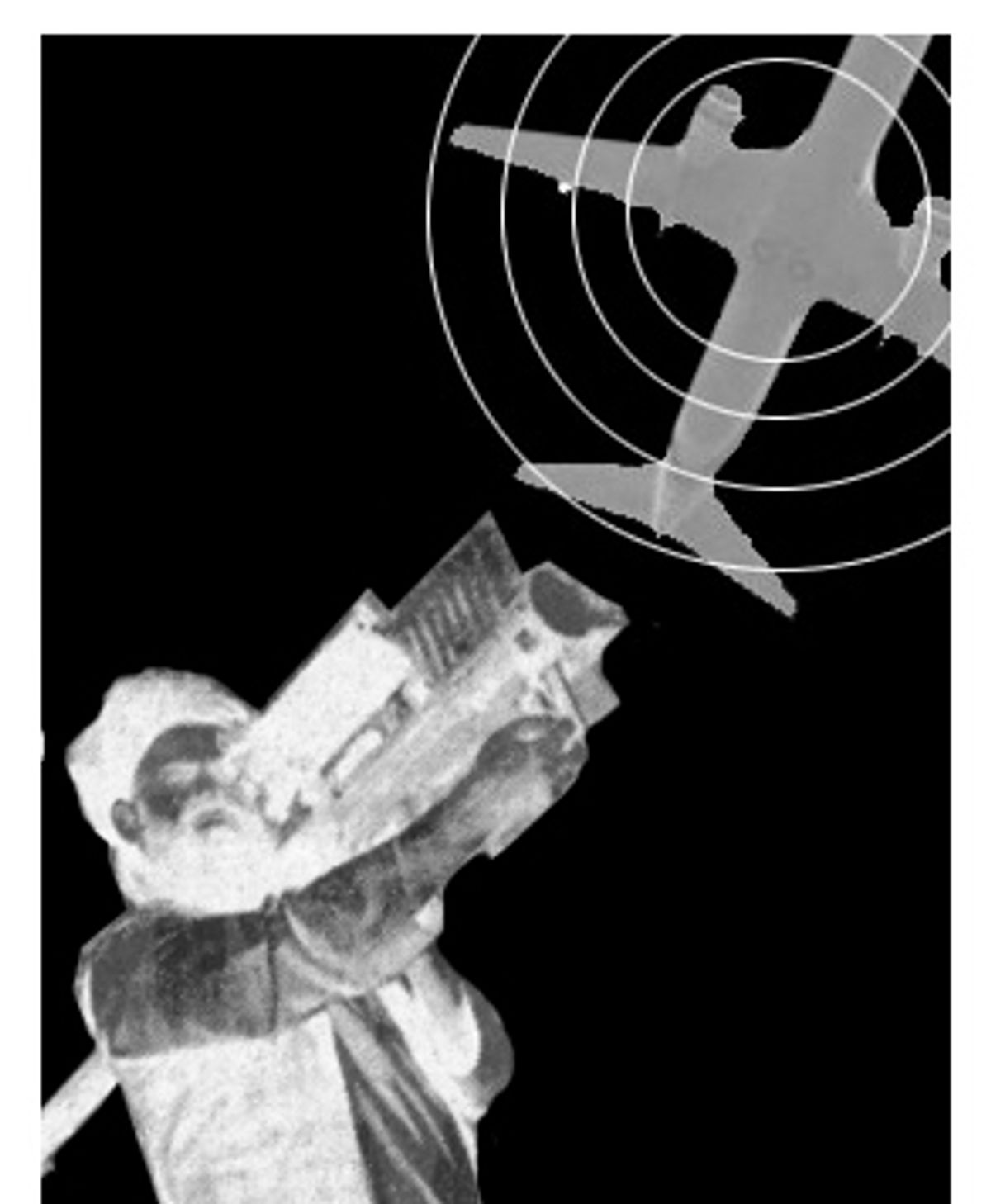

In a series of stories since the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks, Salon has disclosed that the proliferation of shoulder-launched missiles has alarmed airline security officials and many congressional officials. The launchers are small, light and easy to hide, and they are known to be in the hands of al-Qaida and other terrorist organizations. Late last year, suspected al-Qaida terrorists fired on a charter jet filled with Israeli travelers at Mombassa, Kenya, but the missile narrowly missed its target. Top national security officials began meeting last year to assess and address the risk, and some have suggested it would cost around $15 billion to equip 5,000 U.S. jetliners with anti-missile technology. But to date, critics say, the federal government has done almost nothing to prepare for the possibility -- some call it a probability -- that terrorists will use shoulder-launched missiles against American commercial jetliners, either within or outside the United States.

Contrary to the images portrayed in movies, most combat troops and other military personnel do not cram into the back of military transport planes when deploying around the world. Like the rest of us, they usually fly in commercial jets both within the United States and abroad.

Through the Civilian Reserve Aviation Fleet program, the Defense Department contracts with commercial airlines to provide jets and air crews during times of crisis. In return for participating in the program, airlines are guaranteed peacetime business with the Defense Department. The reserve aviation fleet "forms the majority of the DoD's passenger airlift capability," according to Navy Capt. Stephen Honda, spokesman for the Pentagon unit responsible for airlifting military personnel and equipment. By some estimates, over 90 percent of the military personnel moved by the Defense Department are transported on aircraft operated by CRAF carriers. And like every other commercial airliner in this country, these airliners are completely unprotected from the threat from shoulder-fired missiles.

But military craft flying in and out of Baghdad have been targeted at least three times since May by anti-U.S. forces with shoulder-launched missiles. All of those aircraft likely had sophisticated anti-missile countermeasures, and all of the shots missed their targets. Still, the threat of shoulder-fired missiles remains so great in Iraq that the Baghdad airport has remained closed to all but essential military and aid aircraft. That is the risk facing the planes that would ferry up to 20,000 reserves and National Guard troops to the Iraqi capital if Rumsfeld goes ahead with the call-up.

Pentagon documents show that shoulder-fired missiles are the single greatest killer of military aircraft, accounting for well over 50 percent of all combat losses in recent decades. Additionally, Pentagon documents show that these missiles have successfully hit 41 civilian aircraft and destroyed at least 30 of these. In the process, about 1,000 passengers and crew have been lost. Air Force Gen. John W. Handy, head of the U.S. Transportation Command, recently said that the danger posed by shoulder-fired missiles "is perhaps the greatest threat that we face anywhere in the world, and the proliferation of MANPADS is well documented."

Some in Congress are deeply concerned about the elimination of funding to begin protecting the troop-transport aircraft. U.S. Rep. Steve Israel, a New York Democrat and outspoken proponent of federal spending to protect commercial jetliners, blasted the Bush administration in an interview this week for failing to take care of troop-transport planes. "Out of a $400 billion defense budget, $3 million is completely inadequate, particularly against thousands of shoulder-fired missiles in the hands of terrorists including al-Qaida," Israel said. "We have simply got to stop shortchanging this glaring threat to American airplanes."

According to Pentagon budget documents obtained by Salon, the missile defense program for aircraft in the military reserve program would have leapfrogged the lethargic anti-missile efforts currently gearing up at the Department of Homeland Security. In its first year, the Defense Department program would have measured the "heat signatures" of the commercial airliners used to transport troops, and then begun devising anti-missile measures to protect those planes. Measuring the heat signatures is a critical step, since shoulder-fired missiles are "heat seekers" and home in on the infrared radiation given off by aircraft. Currently, the DHS has no plans to conduct similar measurement efforts.

With $3 million, defense officials will be able to record those heat signatures, but little work on missile-jamming equipment will be possible unless money can be found elsewhere in the Pentagon budget.

Should terrorists begin targeting the troop-transport aircraft, there likely will be widespread political and economic effects. "The ability to rapidly deploy military force across the globe is a key element of American power and influence in the world and helps to create the stability and security that is the basis for investment and trade on which the prosperity of the U.S. and others depend," says James Bodner, former undersecretary of defense in the Clinton administration.

A research study currently underway at the RAND Institute estimates that the direct cost of one plane's being shot down - for the loss of life and the cost of the aircraft -- would be $1 billion. The ripple effect of such a loss would likely be enormous, as people reassess the wisdom of traveling by air.

The military has taken a multi-pronged approach to protecting its combat jets and the Air Force's large transport aircraft. It uses intelligence to uncover threats, conducts missions to capture shoulder-fired missiles from terrorists and other groups, and has installed sophisticated systems on its aircraft to jam attacking missiles and direct them away from the targeted aircraft. As a backup, since no electronic countermeasures system is 100 percent effective, the military also designs its aircraft to be able to withstand the detonation of a shoulder-fired missile warhead.

Shortly after the failed missile attack in Kenya last year, the administration formed an interagency task force to seek solutions to the shoulder-fired missile threat. Soon, however, that effort was being criticized for focusing on window-dressing solutions that cost little -- and provide little protection. Confronted by congressional pressure, the administration pledged to put together a plan for combating terrorist missile attacks.

In March, Transportation Security Administration head Adm. James Loy seemed to call for an expedited push to address the threat. Speaking to CBS News' "60 Minutes," he said, "I think the right thing for us to do is to continue the methodical study process that has been undertaken by the National Security Council, not with years of study to come but with weeks of study to come." Still, the administration failed to act. During congressional deliberations leading up to the vote to fund ongoing operations in Iraq, Congress ordered the Department of Homeland Security to come up with a plan to counter the threat from shoulder-fired missiles.

The department delivered a report in May that proposed spending $2 million this year to set up an administrative office to coordinate the anti-missile activities and up to $60 million next year. The White House, however, failed to seek any funding to implement the plan. Instead, the Department of Homeland Security began a much-hyped program that was supposed to have identified one or two promising technologies before the end of this month. Instead, the program petered out. In recent days a department official told Salon that the program "was never going to solve the problem [because] it lacked the necessary funding." Still, despite the department's dismal track record on this issue, the official insisted that a new Homeland Security program -- funded in the first year with $60 million that the Congress appropriated after the White House failed to request any funding at all to address the threat -- will begin the process of finding a solution. In early October, the Homeland Security officials will brief defense contractors on its goals and requirements for a missile countermeasures system for use on commercial airliners. But the program won't yield significant progress before 2006.

"We're heading out on a long, slow jog, when a faster pace is warranted," says Israel. "I am convinced that the threat of shoulder-fired missiles to our commercial airplanes is serious enough to merit significantly more energy and resources."

In the meantime, U.S. troops are being transported around the globe on aircraft that are unable to ward off a missile attack and have not been designed to take a missile hit. For the families of the troops about to be called up and sent to Iraq, this must be a chilling proposition.

Shares