I thought I had seen political dirty tricks as foul as they could get, but I was wrong. In blowing the cover of CIA agent Valerie Plame to take political revenge on her husband, Ambassador Joseph Wilson, for telling the truth, Bush's people have out-Nixoned Nixon's people. And my former colleagues were not amateurs by any means.

For example, special counsel Chuck Colson, once considered the best hatchet man of modern presidential politics, went to prison for leaking false information to discredit Daniel Ellsberg's lawyer. Ellsberg was being prosecuted by Nixon's Justice Department for disclosing the so-called Pentagon Papers (the classified study of the origins of the Vietnam War). But Colson at his worst could barely qualify to play on Bush's team. The same with assistant to the president John Ehrlichman, a jaw-jutting fellow who left them "twisting in the wind," and went to jail denying he'd done anything wrong in ordering a break-in at Ellsberg's psychiatrist's office, where the burglars went and looked for, but did not find, real information to discredit Ellsberg.

But neither Colson nor Ehrlichman nor anyone else I knew while working at the Nixon White House had the necessary viciousness, or depravity, to attack the wife of a perceived enemy by employing potentially life-threatening tactics.

So let me share a bit of history with Ambassador Wilson and his wife. And, well aware that gratuitous advice is rightfully suspect, let me also offer them a suggestion -- drawn from some pages of Watergate history that till now I've only had occasion to discuss privately. Long before Congress became involved and a special prosecutor was appointed, Joe Califano, then general counsel to the Democratic National Committee and later a Cabinet officer, persuaded his Democratic colleagues to file a civil suit against the Nixon reelection committee. And that maneuver almost broke the Watergate coverup wide open. In seeking justice from the closed ranks of the Bush White House, Wilson and Plame should follow a similar strategy.

The hardball politics of Nixon and his people, of course, first surfaced with the bungled break-in and attempted wiretapping at the Watergate offices of the Democratic National Committee (DNC), when the head of security of Nixon's reelection campaign was arrested there along with a small army of Cuban Americans. These activities were, of course, only the tip of an iceberg, a first bit of public evidence of a White House mentality oblivious to the law.

DNC chairman Lawrence O'Brien, an experienced political operator, correctly suspected the worst. He had been harassed by the IRS, deducing (correctly) but not knowing for certain that the audit was being pushed by Nixon himself. After the Watergate break-in, O'Brien quickly realized that Nixon's Department of Justice was not likely to expose this criminal activity, so he filed a civil lawsuit. In his memoir, he later explained why:

"We wanted to get to the bottom of [the Watergate break-in] -- we wanted the whole story, no matter where it led. There was reason to suspect that the break-in and wiretapping had been authorized by the officials of the CRP [Nixon's reelection committee]; and there was the possibility that the trail might even lead higher. We wanted the facts, and we knew they would not be easily attained. One decision we made, acting on [DNC general counsel] Joe Califano's legal advice, was to file a lawsuit against CRP. In this way, the judicial process would help us get to the truth."

Few appreciate the significance of this lawsuit in the unraveling of Watergate. It has been largely overlooked by history. A few years ago, I told Joe Califano about the impact his lawsuit had: Within the White House, it was considered one of the most difficult problems to deal with during the investigations of Watergate. The FBI was no problem -- no one has to talk to an FBI agent. And no Department of Justice is going to haul White House aides before a grand jury. But a subpoena demanding the production of documents, or an appearance to give testimony under oath at a deposition -- that was a serious threat. It also troubled the FBI and Justice Department, keeping them on their toes. It was remarkably effective.

Regardless of whether or not a special prosecutor is selected, I believe that Ambassador Wilson and his wife -- like the DNC official once did -- should file a civil lawsuit, both to address the harm inflicted on them, and, equally important, to obtain the necessary tools (subpoena power and sworn testimony) to get to the bottom of this matter. This will not only enable them to make sure they don't merely become yesterday's news; it will give them some control over the situation. In the case of the DNC's civil suit, Judge Charles Richey, a good Republican, handled it in a manner that was remarkably helpful to the Nixon reelection effort. But any judge getting a lawsuit from Wilson and Plame today would be watched a lot more carefully.

While I have made no effort to examine all the potential causes of action that Wilson and Plame might file, several come to mind. For example, given the fact that this leak was reportedly an effort to harm them, a civil action for intentional infliction of emotional distress could be appropriate. (Because I am not aware of their residence -- the District of Columbia, Maryland or Virginia -- I will only state the law generally.)

Typically, there will be a statute to this effect: "One who by extreme and outrageous conduct intentionally or recklessly causes severe emotional distress to another is subject to liability for such emotional distress, and if bodily harm to the other results from it, for such bodily harm." Most often, these actions fail because the conduct is not sufficiently outrageous. But blowing the cover of a CIA operative by anyone with access to such classified information is outrageous by any standard. By way of comparison, it's been found outrageous for a doctor to refuse to treat an unconscious infant and leave mother and child out in the cold; it has been ruled outrageous for a mortician to mishandle a corpse and lie about it; and it was considered outrageous to recklessly issue a report of a person's death that had not happened.

Also, there is an entire body of law relating to civil actions based on criminal statutes and constitutional activities. Suffice it to say that there are a number of potential causes of action, and I have no doubt that a good civil litigator can fashion a powerful lawsuit for Ambassador and Mrs. Wilson.

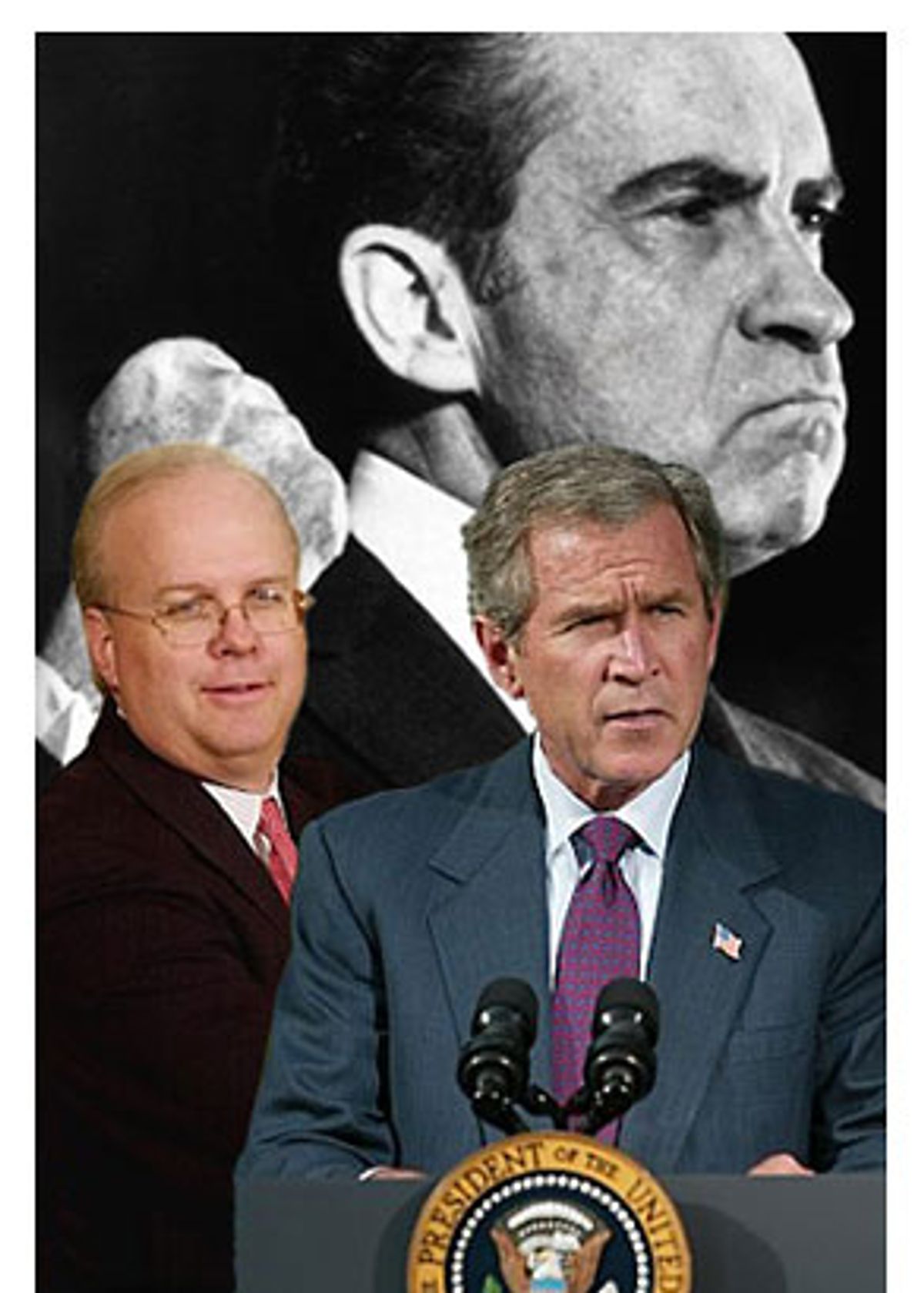

A key question is: Who would they sue? No one has admitted to the dirty deed. In Watergate, the DNC had a hook: They named not only the burglars arrested in their offices but also the Nixon reelection committee, charging a conspiracy to deny the civil rights of Larry O'Brien and other Democrats. From a tactical standpoint, as any lawyer will tell the Wilsons, what's vital is to survive a motion to dismiss, or other such summary action, so that they can conduct all the necessary discovery to find everyone who should be named. Newspaper accounts suggest the first potential defendant might be Karl Rove, who, Ambassador Wilson has been told by reporters, has repeatedly said Wilson's wife was "fair game." And we know this is not the first time Rove might have leaked to Robert Novak, who broke the Wilson story; Rove was removed from the 1992 George H.W. Bush campaign for just such a smearing leak, according to many reports (which Rove has denied).

An attorney will only file such a lawsuit for the Wilsons if he can, in essence (as required under the federal court rules), attest that to the best of his or her knowledge, information and belief, formed after an inquiry reasonable under the circumstances, the lawsuit has not been filed for an improper purpose, that the claims aren't frivolous, that the claims are based on solid law, and that the allegations have evidentiary support -- or will have such support after a reasonable opportunity for further investigation or discovery. In short, while there is a minimum threshold for filing such a suit, it is not a very high barrier. I have little doubt such a lawsuit could be fashioned with little difficulty.

If the Bush White House is anything like the Nixon White House -- and there is increasing evidence of the similarities -- it will respond to such a lawsuit like a stuck pig. Leaking the name of a CIA official can under no circumstances be considered a part of any potential defendants' official duties, so they will not be given representation by the Department of Justice. But how about Wilson and Plame: Should they have to bear the expense of a lawsuit to deal with the harm they have suffered and get to the bottom of what happened? I don't think so, and after talking with several lawyers in Washington, I find I am not alone. I have good reason to believe that one or more law professors in the area might handle the case pro bono, or one or more of the public interest groups might underwrite the lawsuit. Needless to say, that will only cause more squealing by those who want this to go away. They will cry that it's all politics. This is an empty contention -- it was the attack on the Wilsons that was pure politics. But the Bush folks appear to have messed with the wrong man (and woman).

Time after time, Nixon tried to stem Watergate by declaring it was pure politics. But what were his people doing in the Democratic headquarters? Was that not merely dirty politics? To fight the investigations of Watergate, the White House and the Republican National Committee, the Nixon reelection committee kept their surrogates working full time. Democrats who criticized Nixon for not getting to the bottom of who was involved in the DNC break-in were endlessly accused of playing politics with nothing but "a third-rate attempted burglary." This sort of defense, of course, has already commenced from the Bush White House, with the president's surrogates similarly downplaying this vile act of political revenge against the Wilsons. Apparently, they don't realize how Nixonian this behavior is, and Nixon and his aides did not exactly set the gold standard for conduct for any presidency.

Bush's Justice Department, not unlike Nixon's, faces insidious conflicts of interest when investigating the White House. Given the close ties of those on the White House staff with the political appointees at Justice, the conflict is real, not merely an appearance, and actually more serious for the Bush administration's people than Nixon's because there are many more longstanding ties. Equally troubling, the Justice Department has a poor record in this area. For decades, it has been notorious for its inability to uncover leaks, and it has only prosecuted cases handed to it by other agencies that have taken on the work of flushing out leakers. The CIA, for example, refers leaks regularly to Justice, but nothing ever happens. As those familiar with this dismal performance can tell you, one reporter at the Washington Times has printed over 200 classified national security secrets. How the Justice Department has failed to uncover even one is stunning.

But when it is important, the source of a leak can be found. A good example is that of former chief judge Norma Holloway Johnson, who during the Clinton administration's Whitewater/Lewinsky investigations became exasperated with grand jury leaks (since grand jury information is equal to highly classified national security information). The leaks were coming from the office of independent counsel Kenneth Starr, so rather than have Justice probe the leak, Judge Johnson appointed a special master, who found the leaker -- Starr's deputy, Charles Bakaly. The judge tried Bakaly, in a non-jury trial for contempt, and then let him off the hook. She'd made her point. Her inquiry also makes the point that when there is a will to find a leaker, there is a way.

As for claims by the Bush administration that it can avoid conflict-of-interest problems by turning the investigation of leaks about Plame over to career professionals rather than to Bush political appointees, that's nonsense. That would merely turn the clock back to the initial Watergate investigation, which was conducted by career professionals. Years ago, I testified about how helpful those career attorneys were, and as the White House tapes later proved, these professionals (men with impeccable credentials) kept the Nixon White House fully informed of their investigation, as did the FBI, thereby facilitating the coverup.

Of course, Attorney General Ashcroft should appoint an independent prosecutor, or even two, as Calvin Coolidge did (a Republican and a Democrat) to investigate Teapot Dome. That would be the smart move, with a staggering 70 percent of Americans saying he should appoint a special prosecutor, and 83 percent of those polled saying this is a serious matter, according to the Washington Post.

But most importantly, I believe that Wilson and Plame hold the keys to resolving this matter: with a civil lawsuit. This was one of the hidden keys to Watergate, though it was never fully turned. But had Joe Califano's lawsuit not been slowed down by a Nixon-friendly judge, Watergate would have ended much earlier. So can this scandal -- if the Wilsons choose to take that route.

Shares