If your familiarity with Rio de Janeiro's never-ending crime epidemic consists of an infamous "Simpsons" episode or the favela chic of Fernando Meirelles' art-house hit "City of God," then the new documentary "Bus 174" will feel instantly sobering, if not shockingly raw. On June 12, 2000, a gunman hijacked a Rio bus in broad daylight and held a dozen passengers hostage in a five-hour standoff with the police. Ordinarily, such a routine act of violence might not have generated much public fascination, but due to police carelessness, the entire ordeal was caught live on national television, becoming Brazil's closest approximation to the O.J. Simpson freeway chase. The ensuing media orgy enabled the hijacker, a 21-year-old street kid named Sandro do Nascimento, to seize control of the fragile situation and become an instant superstar in the process. (The broadcast scored the highest TV ratings in Brazil that year.)

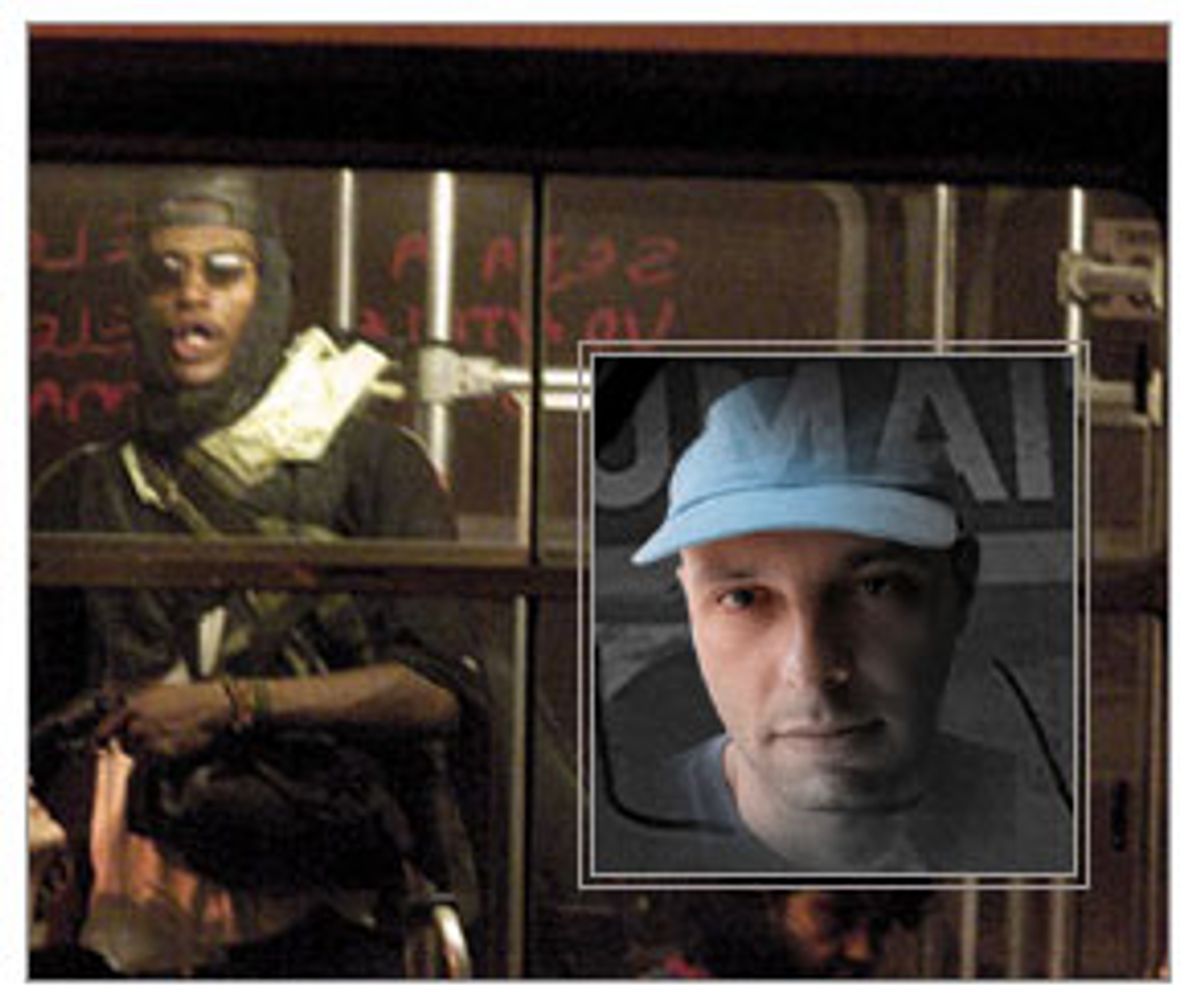

Director José Padilha sifted through more than 24 hours of video footage to reconstruct the events of that surreal day. Supplemented by interviews with cops, social workers and the street kids with whom Nascimento spent much of his life, "Bus 174" mounts an ambitious investigation into the origins of urban violence. We learn that as a child Nascimento watched as gangsters gunned down his mother on her doorstep. At 14, he narrowly escaped death in the Candelaria massacre, a notorious raid in which the police murdered eight street kids. He spent his last years in and out of various institutions, a juvenile delinquent all but invisible to the larger society.

As painstakingly as he chronicles Nascimento's life, and particularly his final hours, Padilha (who is a physicist by training) seems guided foremost by the uncertainty principle. The closer the movie zooms in on Nascimento, the more spectral and elusive he becomes -- like a particle wave in perpetual, unobservable motion. In one unnerving scene, he shoves the barrel of his gun under a hostage's chin and says that he's going to kill her. But the hostage's testimony (culled by Padilha months after the event) reveals a different story: She says Nascimento had no intention of pulling the trigger and that he had instructed his otherwise calm hostages to cry and feign hysteria. Such ambiguity -- psychological and emotional -- pervades "Bus 174" like an alluring fog: The farther in we venture, the less we ultimately understand.

Salon recently spoke with director José Padilha. "Bus 174" opens this week at Film Forum in New York and will open in other major cities later this year. HBO plans a 2004 air date.

"Bus 174" has played to great critical and popular success in Brazil. Do you think people have a need to collectively relive traumatic events and to work them out in their heads?

I don't feel that it was a question of the city needing to revive the event. I felt like it would actually have been forgotten because you have so many violent events like that in the city. After Bus 174, there was this journalist from Global Network who was tortured to death by drug dealers in a favela. I don't know if you heard about that in the U.S. And a few weeks ago, there was a Chinese man who had become a Brazilian citizen and was trying to get out of the country. He was detained by the police and was tortured to death in jail.

So you're saying that movies like "City of God," which show incredible amounts of street violence, are not exaggerating that much after all.

There are no arguments against facts. Eleven people in Rio are murdered every day. Those are the official records. If you take into account that some murders are not reported, maybe the number is 20 for a day. If you add these numbers for a whole year, more people are murdered in Rio in one year than all the people who've been killed in the whole of the Israeli-Palestinian intifada since it began. So it's a reality.

Did you encounter any government resistance while making "Bus 174"? Did anyone try to dissuade you from making an unflattering portrait of the city?

Out of the chaos of the Brazilian government come some good things, one of which is that the government is simply not organized enough to control movies. So you get away with films like this, or like "City of God." In fact, "Bus 174" was partly financed by the city of Rio de Janeiro. I met the mayor once and I asked him, "Don't you think this movie is bad for tourism?" He said it's bad for tourism if you pretend it's not there. You have to be open about what's going on and face the problems.

Yet in the movie when you interview several police officers, some of them are wearing masks. Was this because they had to speak off the record?

It's because if the governor saw their faces, they would be fired, or they would be arrested. One of them was arrested for 30 days for speaking about Bus 174 to a journalist and that was before my film. He spoke on television and he was sent to jail. So there was a great deal of censorship. And it was amazing that one officer agreed to talk to us without wearing a mask -- he was the negotiator. He did it because by that time, the governor was already out of office. Otherwise he wouldn't have done it.

From what we see in the movie, juvenile delinquents often share cells with convicted murderers and other dangerous felons.

The killers control these kids in jail. They set the tone. Some of these kids will even grow to admire the killers because the killers have money, they can pay off the guards, they can give you favors. It doesn't make sense to classify them as children and then throw them all in the same place. It's like the state couldn't care less. Filming in prison was definitely a shock to me. I had trouble sleeping that night. It was like 15 people in a room with three beds and no baths -- all on top of each other. Some of them had leprosy or other skin diseases. It was torture in a sense.

The media played a complicated role in the hijacking. They clearly contributed to the atmosphere of chaos, and yet without them, this movie would not exist.

The media had a huge influence on the outcome of the event because it had an influence on the behavior of the hijacker, Sandro, and also on the behavior of the police. On one hand, the police wouldn't take the sniper shots because the governor didn't want someone to be killed on live TV at that time of the day. So that actually delayed the process and put the life of the hostages at greater risk. In a second sense, Sandro seized that opportunity to convey a certain message. He would have hostages write on the window of the bus. He would portray himself as more violent than he actually was so that he would get more attention. So the media not only made the movie possible, they actually made the whole event possible.

Your movie retraces Sandro's life story in terms of the state institutions he passed through as a street kid. It seems to be as much about the juvenile justice system in Brazil (or lack thereof) as it is about Sandro specifically.

My vein was sociological rather than psychological. I truly think that Sandro represents a certain class or group of people that is left out of society, and who are badly mistreated by the state, and have no human rights, and these are the street kids and the juvenile delinquents. I could not make the movie too individual to Sandro because I think there are many kids who are exactly in the same place as he was. And that's the point of the film. By telling his story, the movie tries to build a social criticism about what is going on in Brazil today.

And what is that criticism?

It's the idea that in Brazil, and elsewhere too, people think that violence is created either by misery -- like if you have misery, you will have violent people -- or they think that violence is a product of repression. I think Sandro's life story shows that there is more going on, that the state is actively producing violent people by mistreating street kids. State institutions are shaped in such a way that whoever crosses them has a good chance of turning out to be a very violent individual. If you look at the 1992 Candelaria massacre, it was a massacre made by cops, and cops are representing the state.

I read that the police now use your movie to train their officers.

Everywhere except in Rio. In Rio, they pretend it never happened.

Have you had any contact with the Rio police since making the film?

A lot, because I'm working on a screenplay about the police. And I'm working with eight police officers informally. It's a fictional film. But I'm basing it on real stories. I can't make a documentary because it would be hell, so I'm interviewing them informally. Some of them have become friends. I still think there's a movie to be made about violence in Brazil, and that's from the perspective of the police because they are a big part of the problem. "City of God" addresses drug dealers; "Bus 174" addresses street kids. There is a third entity involved and that's the police, and nobody addresses them. I felt like I still have something to say about this before I move onto another subject. I learned too much about the police.

As violent as Rio can be, you chose to open the movie with a serene aerial shot of the city. Why did you choose to open that way, and why do you keep coming back to that shot?

There are two reasons. The first one -- which I don't have to explain to a Brazilian audience -- is that it's the route the bus took until it stopped in the place where it was hijacked. So I open the film with the route Bus 174 took. The reason I chose that shot is to tell you that even though the movie is the story of an individual, it's actually representative of the whole city. The best way I found to do this was to show these images of the city in a big, visual way.

It's also very beautiful.

Yes. It's beautiful because Rio is beautiful.

Shares