On Sept. 17, the Bush administration handed Congress a spending bill that reads like a bleeding-heart liberal's legislative fantasy, a massive, government-funded infrastructure revitalization program of the kind not seen since the days of FDR: It calls for $800 million for the police, $300 million for firefighters, and almost $3 billion for clean water systems. It sets aside tens of millions of dollars to build thousands of new public housing units, but it warns that much more money will be needed in the future. The bill allocates about $1 billion to spend on healthcare, including $150 million for a state-of-the-art children's hospital. There's even $5 million to build a women's center and a million dollars for a new museum.

Is George W. Bush finally displaying the compassion long advertised to run through his brand of conservatism? Not exactly. As you may have guessed, this particular plan isn't aimed at fixing the problems of Boston or Boise but those of Baghdad and Basra and Tikrit and Najaf. Congress is now debating -- and, after many adjustments, will likely approve -- the president's plan to rebuild Iraq's schools, hospitals, highways, prisons, the electricity grid, railroads, and every other institution of civilized society; of the $87 billion the administration seeks, about $20 billion is earmarked for Iraqi nation-building.

Iraq desperately needs rebuilding, and it might seem churlish to question what the administration has requested. But when the price tag is in the tens of billions, one can't help wondering: How much money will actually find its way into the hands of Iraqis? Who will profit from this reconstruction windfall?

In Congress, Democrats are asking the same questions -- and many are saying that the spending request is nothing but a huge gift to Bush's moneyed friends. "Item after item [in the request] reads like a government contractor's wish list," Rep. Henry Waxman, a California Democrat, wrote in a recent letter to the White House's Office of Management and Budget.

Is Waxman right? Is the rebuilding request tailor-made to pad the accounts of U.S. corporations, and in particular, those with good connections to the White House? It's hard to get definitive answers to this question, mostly because nobody seems to know how much money Iraq needs, and, consequently, whether the president's plan is too big, too small, or just right.

"I'm hard-pressed to criticize the particular numbers -- I can see an argument for why all of these things could be good for Iraq," says Bathsheba Crocker, a post-conflict reconstruction expert at the Center for Strategic & International Studies. "But that doesn't mean that the U.S. taxpayer can or should afford all of these things, and you do have to protect against padding of the contracts."

This reconstruction fog raises all sorts of vexing problems for the average concerned citizen. You want to support the rebuilding in Iraq, but you don't want to overpay. You want to make sure the Iraqis get what they need, but you're not too thrilled about Halliburton getting a blank check. It'd be great if the work was done in a transparent manner, but since when does a government program work like that? And is there a danger of the president's pals making off with the biggest prizes -- and are they trying to do that? Of course.

What you need is a guide to the main players in Iraq -- a handy list of the various interests who are winning, trying to win, losing, and trying not to lose. You need to know what makes the work in Iraq so expensive, and so prone to cozy political relationships. And you need to see why rebuilding the country is going to be a long, difficult, ugly process.

Fortunately, we have created such a guide for you:

The lobbyists. Late in September, the Washington newspaper The Hill reported that some of the president's closest political allies had created a new firm, New Bridge Strategies, whose main goal is to help corporations "evaluate and take advantage of business opportunities in the Middle East following the conclusion of the U.S.-led war in Iraq." The company, which is headed by Joe Allbaugh, Bush's chief of staff in Texas and his campaign manager in 2000, was not exactly hard to find -- it has a Web site that boasts of its intimate ties to government officials: "New Bridge Strategies principals have years of public policy experience," the site says. The company's directors "have held positions in the Reagan Administration and both Bush Administrations and are particularly well suited to working with international agencies in the executive branch, Department of Defense and the U.S. Agency for International Development, the American rebuilding apparatus and establishing early links to Congress." Other New Bridge partners include Ed Rogers, vice chairman of the lobbying firm Barbour Griffith & Rogers, and a close political aide to George H.W. Bush; and Lanny Griffith, also at Barbour Griffith, who served in several positions in Bush senior's White House, including as Southern political director in the 1988 campaign.

You might think it a bit unseemly for the president's close friends to use their proximity to power to profit from a war that the administration assured us had nothing to do with profiteering, but that's only because you're naive. According to Allbaugh and the others at New Bridge, having friends in high places is no reason not to make money; that's how things work in Washington, it's not at all unusual. "Because my friend is president of the United States, I'm supposed to check out of life?" Allbaugh asked the New York Times on Friday. (Nobody at New Bridge Strategies -- nor at any of Washington's other lobbying firms looking for work in Iraq -- returned Salon's repeated calls.) "I have nothing to hide. I'm straightforward. I deal my cards on top of the table," Allbaugh told the newspaper, and he added that there was in fact something honorable about working in Iraq. "We fought a war, we displaced a horrible, horrible regime, and as a part of that we have an obligation to help Iraqis. We can't just leave in the middle of the night."

On its Web site, New Bridge Strategies says that the business opportunities in Iraq are of an "unprecedented nature and scope," but what that means specifically is left up in the air. So far, it appears that New Bridge's only public client is MCT Corp., a cellular phone company based in Alexandria, Va., that has previously built phone systems in the former Soviet Union and Afghanistan. In August, MCT and New Bridge Strategies submitted a bid to build the mobile system in Iraq, but New Bridge's political ties do not appear to have helped it very much. On Monday, the Iraqi communications ministry announced that it had awarded mobile phone bids to three Middle Eastern firms.

But that may have just been New Bridge's bad luck. In Iraq, virtually everything that gets built is built with the approval, if not by decree, of Washington -- which is, after all, funding the entire endeavor. Undignified as it may appear, New Bridge's pitch is rather logical, and after the new spending bill is signed, it's likely that many companies will decide that the best way to get to Baghdad is by way of K Street.

And perhaps that's why New Bridge Strategies is not the only lobbying firm looking to push work in Iraq. On Oct. 2, the Washington Post reported that the Livingston Group, the firm headed by former Rep. Robert Livingston -- the Republican whose plans to become speaker of the House in 1998 unraveled when it was revealed that he'd carried on an extramarital affair -- is also quite interested in working for companies looking to take part in the Iraqi reconstruction. One firm Livingston is helping is De La Rue, a British paper company. De La Rue has already received a contract to print Iraq's new currency, and it wants to work on secure travel documents, too. A Livingston lobbyist told the Post that he was rather busy pitching De La Rue's case to a number of influential members of Congress. "We're trying to get the right people to ask the right questions of the right people," he said.

De La Rue, incidentally, provides a good indication of how lucrative working in Iraq can be. The company's fortunes had been flagging recently; in July, the Justice Department began an investigation of De La Rue to see if one of its subsidiaries was involved in a scheme to fix the prices of holographic security stickers used for Visa credit cards -- news of the investigation sank De La Rue's stock. Thanks to Iraq, things now look fine for the firm. In September, the company said that its profits would soar, mostly due to its reconstruction work.

Halliburton. In March, Kellogg Brown & Root, a subsidiary of Halliburton, signed a contract with the Defense Department to fight fires in Iraq in the event that Saddam Hussein tried to destroy his oil fields during the war. The contract seemed fishy from the start. It was awarded on a "no-bid" basis; only Halliburton was asked to do the work. The Defense Department has subsequently been suspiciously cagey about its details, slow to answer questions about the contract's size and specific purpose. Only in April, a month after it was signed, did the Army Corps of Engineers disclose (in response to questions from Henry Waxman) that the contract was potentially worth $7 billion to Halliburton. It took another month for the Army Corps to say that Halliburton would not only fix damaged oil facilities but would also operate oil centers and even distribute the oil. (Waxman's complete correspondence with the Army Corps is here.)

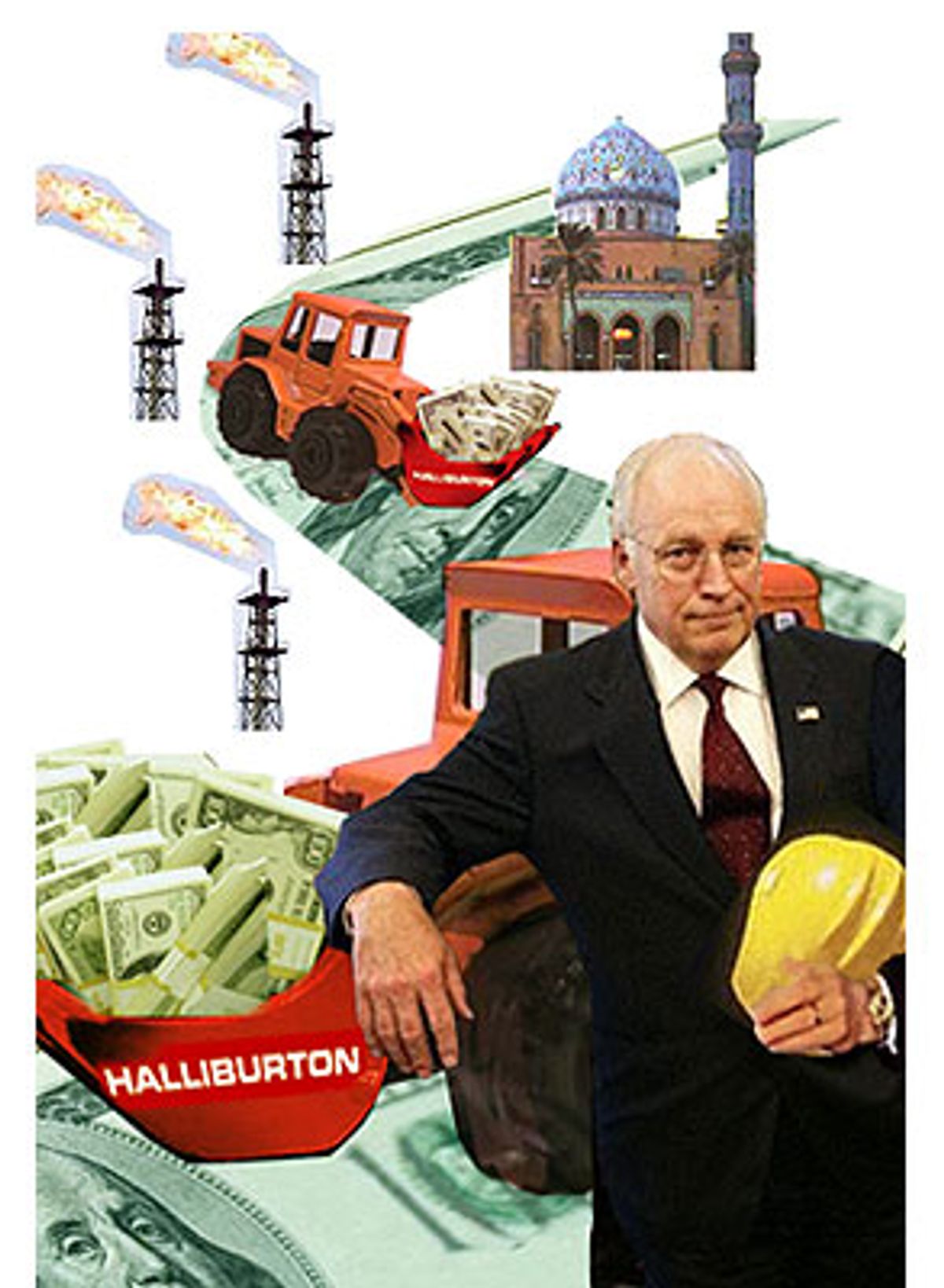

Why was Halliburton awarded this lucrative, expansive contract on a no-bid basis? To most people, the answer is obvious -- in the 1990s Halliburton was run by Vice President Dick Cheney. There is no proof that Cheney's ties to the company had anything to do with Halliburton's good fortune in Iraq, but there are enough clues to make you suspect the worst. Halliburton's story -- a no-bid contract, a friend in the highest place -- has all the hallmarks of cronyism, and it ought to stand as the model of how not to reconstruct Iraq.

Both Cheney and Halliburton say that he played no part in the awarding of the contract. "Nobody has produced one single shred of evidence that there's anything wrong or inappropriate here, nothing but innuendo, and -- basically they're political cheap shots is the way I would describe it," Cheney said on "Meet the Press" on Sept. 14. "I don't know any of the details of the contract because I deliberately stayed away from any information on that, but Halliburton is a fine company. And as I say -- and I have no reason to believe that anybody's done anything wrong or inappropriate here."

In an e-mail to Salon, Wendy Hall, a spokeswoman for Halliburton, echoed Cheney's denial of impropriety. "There have been many allegations that Halliburton received the contract for the reconstruction of Iraq because of political influence," she wrote. "Certainly it's easier to assign devious motives than to take the time to learn the truth." The real reason Halliburton was awarded the contract, Hall said, is because of "our unique combination of business experience in defense contracting, engineering and construction and oilfield services." Hall added that "Our employees in the Middle East are building housing, preparing meals, delivering the mail and providing many other vital services for our troops. Our Halliburton people are sharing the hardships and the risks. Three have lost their lives while working there."

At the same time, though, Halliburton has made quite a bit of money in Iraq. So far, it has received about $1.2 billion under the oilfield contract -- more money than any other firm working in Iraq. Moreover, Cheney's insistence that he has no financial stake in the company is dubious. Since he became vice president, Cheney has continued to receive checks in deferred compensation from the company -- he got almost $150,000 in 2001 and $162,000 in 2002, and he will keep getting money until 2006. The White House denies that this represents a financial interest in the company; because he purchased an insurance policy on the compensation, Cheney will get the money regardless of Halliburton's fortunes. In addition, he has agreed to donate the money to charity. In late September, however, the Congressional Research Service concluded that despite these measures, the paychecks represented an actual stake in Halliburton.

The web of coincident interests here is almost comical -- indeed, the most artful criticism of the Halliburton story, the one that several of its critics mention, is a joke David Letterman made on his show. The president "is asking Congress for $80 billion to help rebuild Iraq," Letterman said. "And when you make out that check, remember -- there are two L's in Halliburton." In September, the activist group American Family Voices featured Letterman's quip in an anti-Bush ad it ran in five states. Is this the image the Bush administration wants for its mission in Iraq?

There is perhaps one silver lining to Halliburton's dark deal with the government -- it has so offended lawmakers that they've decided to put an end to no-bid contracts. On Oct. 2, during its deliberations over the Iraq spending bill, the Senate passed an amendment that requires all contracts in Iraq to be awarded only after a rigorous bidding process has been conducted. The House is expected to follow suit.

Bechtel In its long history of government work, this privately owned San Francisco firm has built some of the largest public projects in the world -- including the Hoover Dam, the subway systems in San Francisco and Washington, the tunnel under the English Channel, and many American nuclear power plants -- and, at least according to its critics, it has also built something even more valuable: close connections to the most powerful people in the country. Former Reagan administration officials Caspar Weinberger and George Shultz have worked for the firm (Shultz is still on its board). In February, the company's CEO, Riley Bechtel, was named, along with dozens of other executives, to the president's Export Council, a White House trade advisory group.

Critics charge that it was Bechtel's ties to Republicans that helped it win one of the most lucrative Iraq rebuilding contracts -- a $680 million infrastructure development grant awarded by the U.S. Agency for International Development in April. (Since then, the contract has ballooned beyond that initial sum; according to the USAID, Bechtel has so far received more than $900 million in orders through the contract.)

While Bechtel is certainly a skilled player in the Iraq game, its operations are altogether more routine, and therefore more defensible, than those of Halliburton, a company with which it is frequently lumped together for criticism. Bechtel's contract with the government was awarded in a semi-competitive bidding process (foreign firms weren't invited to apply) and there's no sign that it benefited from special favors, beyond the favors that usually accrue to giants in the military industrial complex. The firm also maintains a Web site that is frequently updated with detailed information about its work in the country; nothing about its plans in Iraq are secret.

That's not to say Bechtel doesn't have its critics. In his letter to the OMB, Henry Waxman charged Bechtel with blocking Iraqi companies from participating in the rebuilding work. Waxman said that he's uncovered evidence showing that Bechtel requires local companies to carry expensive insurance plans in order to be considered fit to subcontract from Bechtel. Waxman also said that the type of contract Bechtel has with the government -- a "cost-plus" contract, in which Bechtel is paid a certain fixed fee over its costs, meaning that it's guaranteed to make money -- provides little incentive for the company to reduce costs by subcontracting to Iraqis. "It is easy to understand how this arrangement is lucrative for [Bechtel]," Waxman wrote. "But what is unclear is how these arrangements protect the interests of the U.S. taxpayer or further the goal of putting Iraqis to work rebuilding their own country."

Michael Kidder, a spokesman for the company, said that Waxman's assessment of Bechtel's work is simply incorrect. "The congressman's letter inaccurately described our method of hiring Iraqi subcontractors," Kidder said. "There is no bond industry in Iraq, but this lack of construction insurance has never prevented Bechtel from awarding any subcontracts to Iraqi firms. Following USAID's direction and their priorities, a vast majority of the subcontracting work Bechtel has awarded has gone to Iraqi subcontractors." Of the 133 subcontracts the company has awarded, 98 have gone to Iraqi firms, the company says on its Web site.

Since the eve of the invasion, when Bechtel's headquarters became a prime San Francisco protesting spot, the company has generally tried hard to counter the charge that it is profiteering from the war and that it won its contracts in Iraq through its political ties. Online, Bechtel has posted a list of "media inaccuracies" that it says the press routinely reports as fact. "Through endless repetition, rather than facts, Bechtel has gained an undeserved reputation as a secretive company that succeeds through powerful friends in high places," the site says. "Over the years, we have certainly built good relationships with important people. We network like anyone in business or the professions ... But the implication that Bechtel wins business or succeeds in a highly competitive marketplace through political connections is misguided and false."

Security guards. Iraq, as you may have heard, isn't exactly a pleasant place to do business, and when companies like Bechtel set up shop there, they're finding that thinly stretched American forces aren't always available to protect corporate interests. Instead of relying on the military for help, many companies are hiring their own protection -- elite security-service firms that provide executives with armed guards, convoys of Humvees, and all manner of amenities in order to stay alive in Baghdad. The security business is one of the few growth industries in postwar Iraq, a fact that can't be heartening to the Bush administration.

Security firms began gearing up for work in Iraq before the war, when they predicted that the chaos immediately following regime change would create temporary opportunities for their services. "We didn't know at that point how difficult it was going to be, and I think it's exceeded our expectations," says David Claridge, the managing director of Janusian, a British security firm working in Iraq. He says that few people in his business predicted "the longevity of the problem, the depth of the problem" in securing Iraq. "Probably everybody inside and outside government failed to estimate the situation."

There are at least 100 security firms working in Iraq today; most are British (Claridge says that the Brits are "regarded as the best, even by American customers") but some large American companies have won choice security contracts with the government. DynCorp, a subsidiary of CSC, an American military contractor, has been tapped to train Iraq's police force. Vinnell, a division of Northrop Grumman, is training the Iraqi army. (If you're a former Special Forces officer who can't find a job in America, you might want to consider working for Vinnell in Iraq.)

The unsafe operating conditions in Iraq have clearly hampered the rebuilding effort, and the need for private security firms likely accounts for the larger-than-expected reconstruction costs. "One of our major clients is entitled to protection from the U.S. military in Baghdad," Claridge says, "but waiting for them left three- or four-hour delays just for their convoy of Humvees to show up. For them the only real solution was to move to private security." Claridge adds: "There's a connection between security and reconstruction. The two have to move hand in hand, and private security has the capacity to make up what is missing in the coalition effort. There isn't capacity in the military to deal with the reconstruction process."

The French. On a trip to Paris in early October, Alan Larson, the undersecretary of state for economic affairs, told a business conference that the United States is quite willing to have French firms work in Iraq. "The door is open for French companies to participate in infrastructure contracts in Iraq," he said, according to AFP. "We're open to companies from all over the world regarding the rebuilding of Iraq."

Beyond that remark, however, it appears that few French companies are participating in the country, and the French government -- along with the Germans and just about everyone else in the world -- has pledged relatively small sums for the reconstruction effort. Late in October in Madrid, the United Nations will hold a donor conference to raise money for Iraq; the U.N. wants about $35 billion, but only about $1 billion has been pledged so far. One wonders how much more money we'd have available if Donald Rumsfeld would learn to measure his words.

The Iraqis and the Americans. The question of whether Iraqis will ultimately benefit or suffer as a result of the U.S. occupation is the most important, and freighted, issue of the war, and it can't be answered here. But it's important to note how firmly the financial fate of the average Iraqi citizen is now dependent on the continued goodwill of the average American taxpayer. At least for the next few years, until Iraq regains its oil production capacity, the country will run on U.S. dollars. And as we all share the same pool of money, our fortunes will be mutually exclusive: When the Iraqis get money, Americans will lose money, and vice versa. This situation cannot make for a fast friendship, and it's further complicated by the political imbalance: Because it's the Americans who get to vote, the Iraqis ought to be wary.

Indeed, the Iraqis are already starting to lose. After the president presented his reconstruction plan to Congress, lawmakers immediately began trimming it. In the House, Bill Young, the Florida Republican who chairs the Appropriations Committee, has "scrubbed" the bill of about $1.7 billion of the president's reconstruction request. Young deleted the $50 million the administration wanted to buy cars for the Iraq's traffic police; $153 million for "solid waste management," including the purchase of 40 trash trucks; $9 million for creating ZIP codes in the country; and the $150 million to build that advanced children's hospital in Basra.

Meanwhile, in the Senate, many Democrats and some Republicans are arguing that at least some of the money the U.S. provides to Iraq should be paid back when Iraq becomes self-sustaining. The Iraqis are obviously not pleased with this plan, and members of the governing council have cautioned senators that Iraq is already heavily burdened with Saddam Hussein's loans. But the idea of lending Iraq its reconstruction money has obvious political appeal in the U.S. -- Americans faced with a ballooning deficit and the hazy notion that Iraq is sitting on billions of dollars in oil wealth might think it only fair that Iraqis pitch in. As the conservative syndicated columnist Cal Thomas wrote recently, "Why should the Iraqis complain? It's their freedom we bought. Let them help pay for it."

But the Iraqis didn't ask for the war, and they didn't volunteer to pay for it. "I'm sympathetic to the argument that it would be nice if the U.S. could get paid back some of this money," says Bathsheba Crocker, the reconstruction expert at CSIS. "But I don't think the loan is the way to do it. I'm worried about how it looks to make Iraq fairly heavily indebted to the United States. It's not something that looks all that great given the heavy degree of suspicion about what our motives are here."

In other words, we wouldn't want to be in the position of reminding the Iraqis that, when they make their checks out for the reconstruction, there are two L's in Halliburton.

Shares