Three times a week, 48 weeks a year, a four-man team drives a huge yellow Hummer to a different location. It might be a college or high school campus, a major fraternity gathering, an NAACP event, MTV's Spring Break, or BET's Spring Bling: If lots of African-American teens will be there, the Hummer wants to be there, too.

Spray-painted with patriotic images (a rippling American flag, a smiling white woman in a U.S. military officer's uniform), the yellow Hummer is the signature vehicle for the U.S. Army's "Taking It to the Streets" campaign, a hip-hop-flavored tour launched a year ago by Vital Marketing Group, the Army's African-American events marketing team. During these events, the Taking It to the Streets team lets possible recruits hang out in the Hummer, where they can try out the multimedia sound system or watch Army recruitment videos. The Army's team often throws contests, too: Which possible recruit can shoot the most baskets, do the most push-ups, go up the rock-climbing wall the fastest? The winners are awarded Army-branded trucker hats, throwback jerseys, wristbands and headbands. Want a customized dog tag? They've got a machine that makes them. Want to see what it's like to fly a plane? There's a flight simulator.

It's all to convince urban teens that the Army understands hip-hop culture: The Army knows you play basketball and wear jerseys, because the Army is down with the streets.

"You have to go where the target audience is," says Col. Thomas Nickerson, director of strategic outreach for the U.S. Army Accessions Command, who says that the Army just reached its recruitment goal of 100,200 enlistees this year. "Our research tells us that hip-hop and urban culture is a powerful influence in the lives of young Americans. We try to develop a bond with that audience. I want them to say, 'Hey, the Army was here -- the Army is cool!'"

But critics say that the Army's co-optation of hip-hop in its streetwise campaign is misleading, because it markets a life-changing and possibly life-threatening commitment as a fun, cool consumer choice. And some, like Rep. Charles Rangel (D-N.Y.), who argued for a reinstatement of the draft in January, voice concerns about the overrepresentation of people of color in the Army.

"One of the reasons why I advocated the draft is because, in terms of a national crisis, we should have shared sacrifices," Rangel says. "When the government says we have to stay in Iraq, we have to show that we're prepared to lose lives, the 'we' should be a broad cross-section of America. They're not asking all of America: They've targeted those Americans who are not getting a fair shake in our society."

African-Americans and Hispanics are consistently overrepresented in the armed forces. Even though the numbers have evened out a bit this year, the 2003 Army is 16 percent black, compared with 11 percent of the country, and 13.4 percent Latino, compared with 11 percent of the country.

The Vital Marketing Group is about to take its recruitment campaign for African-Americans a step further by teaming up with hip-hop bible the Source. This fall, Vital will launch a new tour separate from the Taking It to the Streets campaign: The Source Campus Combat Tour will start in late October, hitting five Northeastern college campuses with high percentages of African-American students. Like Taking It to the Streets, the Campus Combat Tour will feature interactive exhibits and physical challenges, but Campus Combat culminates in a grand MC battle judged by the Source's editors.

"When I saw the Source was teaming up with the Army, I was outraged," says Bakari Kitwana, former executive editor of the Source and author of "The Hip-Hop Generation: Young Blacks and the Crisis in African-American Culture." "It's a betrayal of their readership. The military has historically used African-Americans, while the country has not done justice to African-Americans."

Niche marketing to minorities is a recent development for the Army. Two years ago, the Army's newly hired advertising agency, Leo Burnett, threw out the stale 20-year-old "Be All You Can Be" tagline and replaced it with a jazzy new campaign called "Army of One." This heavily researched and focus-grouped motto -- emphasizing the Army's recognition of each soldier's individual talents -- and its accompanying advertising blitz are especially geared toward the short attention spans of the 72 million Generation Yers. "It's becoming really difficult to establish brand loyalty, because kids are bombarded with multiple messages," says Joseph Anthony, CEO of Vital. (According to American Demographics magazine, the average teen takes in 3,000 marketing messages a day.)

To compete with all the other brands vying for kids' attention, the Army launched a dynamic, interactive Web site with a strong cyberrecruiting team, multilingual chat rooms, a downloadable "America's Army: Operations" video game, and new commercials focused on Army skills that easily translate to civilian life. And there are Army of One campaigns tailored to specific groups. Muse Cordero Chin, the Los Angeles-based agency that heads up the African-American-geared ad campaign for Leo Burnett, will roll out print and TV ads predominantly featuring blacks early next year. (Muse works closely with Vital, which creates and markets the campaign's events.) San Antonio's Cartel Creativo has developed Spanish and English ads featuring Latin music for the Hispanic community. And for the past year the Army has sponsored a NASCAR car and recruited at races; the mostly white, rural NASCAR audience has already generated over 40,000 leads for the Army.

Companies discovered a long time ago that utilizing hip-hop culture -- the musicians, the clothing, the lifestyle, the accoutrements -- is the ticket to selling products to teenagers. Sprite's sales skyrocketed after it launched its "Obey Your Thirst" campaign geared to urban youth. When Tommy Hilfiger's clothes became popular with rappers, his sales shot into the billion-dollar range. McDonald's just signed Justin Timberlake, the poster boy of white soul, to do a hip-hop jingle, produced by the superstar duo the Neptunes. While most hip-hop advertising is an attempt to attract both those who live the hip-hop lifestyle and those who just covet it -- the Army is specifically targeting black youth with their new Source-sanctioned campaign. Since everyone else is marketing with hip-hop -- and since it works -- why shouldn't the Army?

A majority of African-American kids are hip-hop fans, so marketing with hip-hop just makes good business sense, says Vital's Anthony. "[This campaign says] 'We want to come to your environment instead of trying to get you to come to ours,'" he says. "The Army wants to better understand your community." (It helps that all of Vital's employees are young and black, Anthony says. "The African-American market is more responsive to marketing that's communicated to them through people who look like them. There's more of a trust factor there.")

Everything about the campaign, down to the headbands and Army jerseys, should send that message. "Those are big fashion statements in the urban community right now, but before [Vital] was involved, those types of premiums didn't exist," says Anthony. "We're trying to make the Army more relevant and utilize more of these trends. If we make Army apparel a part of their wardrobe, it just creates a connection. They're able to see the brand in a different light, as cool."

Vital has big plans for the partnership with the Source. It doesn't stop with the Campus Combat Tour: Vital hopes to use the 488,000-circulation subscription list for direct-marketing campaigns, create some cross-branded Web sites, throw more Source-branded events, and possibly even appear in the editorial content of the magazine; eventually, there may be reader contests in which the winners will appear in the Source.

Right now, the partnership is in a test period, says Anthony, to "see how the relationship bears fruit," but both the Army and the Source say they hope to expand the tour next year. And Vital wants to partner with other "urban platforms," like Vibe magazine and BET -- albeit cautiously. "We don't want to come out of the gate seeming as if we're trying to buy our way into urban culture," Anthony says, "and we don't want our media partner to be perceived as if they're selling out for money."

But what if that happens? "We've just got to try and position this as a monumental shift in the U.S. Army's ideology in approaching urban youth," he says.

Besides the Source tour in the Northeast and the nationwide Taking It to the Streets campaign, Vital produces another recruitment tool for the Army, a comedy tour that travels to historically black colleges in the Southeast. But Campus Combat is the only tour with another well-known and respected brand attached. And that's critical: It's not easy to convince a bunch of African-American teens that the Army might be their best career choice, but with the Source, the oldest and best-known hip-hop magazine, behind it, the Army gains some much-needed street cred.

"It gets us access," says Col. Nickerson, of the Army-Source partnership.

It makes sense that the Army's looking to hip-hop to attract urban youth, says Craig Werner, a professor of Afro-American Studies at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. "They know that to sell themselves they need to plug in with the culture," he says. "The Army has been the most egalitarian institution in the U.S., bar none, since the desegregation during the Korean War. If an African-American kid is looking for a career in which talent and character will be rewarded, there's no better place than the Army. Having said that, I find the whole thing pretty disgusting. It's an attempt to capitalize on desperation. We've created a job market in which [young African-Americans] don't have a damn chance."

The overrepresentation of minorities in the Army is often cited as proof of the continuing struggle for people of color in the mainstream economy. The Army needs to target ethnic groups, says Kendall Martin, account supervisor at Muse Cordero Chen, because it needs to "mirror" the country. "The Army wants to make sure it improves on representing all groups," he says. "The Army wants to look like America."

But the Army doesn't really look like America, and with a volunteer service, it never will. And considering that one of the Army's main draws is money for college, it's definitely not economically diverse; kids who don't need those incentives aren't as enticed to enlist.

"If you're a middle-class black kid, you're not enlisting, any more than any middle-class white kid is enlisting," Werner says. "The Army has nothing to do with the general profile of American culture. It's lower middle class, disproportionately black and brown, and disproportionately Southern and rural."

Nickerson says he doesn't have any information on the socioeconomic demographics of the Army's enlisted men. "We don't focus on economic backgrounds," he says. "If you qualify to join the Army, I don't care what your economic or social status is."

Since the campaigns tailored to minorities were launched only this past year, it's too soon to measure their impact. But the Army has hit its quota of enlistees -- before deadline -- three years in a row.

"I think you underestimate the commitment of young Americans," Nickerson says, when I ask how the Army can possibly hit its numbers given the combative state of global affairs. (After all, you've got to wonder if the flashy ad campaigns and free headbands will keep recruitment numbers up as the body count in Iraq continues to rise.) "We've got the best recruiting force in the world. We've got a soft economy, and we've got opportunities that resonate with young Americans."

For people of color, the economy's slide has been especially hard: Last month's census data saw poverty numbers rising for all Americans, but especially for blacks. A quarter of African-Americans are living in poverty.

It's one of the reasons why the Army-Source campaign infuriates Kitwana. "The Army is providing jobs, and I think that is a good thing, but we have to put that in context: Why does our country not have jobs for young people?" he asks, pointing out that unemployment rates for black youth are twice the rates for whites.

"One of the things that [African-Americans in the Army] complain about is that we're over here helping these people, and that's all good, but when we come back home, the hood is fucked up," says Kitwana, who researched the military's economic effect on young African-Americans for "The Hip-Hop Generation." "We can be using this same energy to get drugs out of our community, to redevelop the economic infrastructure. It feels empty, as important as it is, to know that we're going back home to that."

"Look at it as the Army returning to that community a better person and a leader in that community," counters Nickerson. "Young Americans who join the Army leave the Army a better person."

Chris White, the Source's vice president of corporate sales, says there's nothing to criticize about its partnership with the Army. The Source is just helping an important Source advertiser get its message out to kids. "The Army has made a very strong advertising commitment for the year," he says, adding that these days, advertisers are more interested in marketing partnerships, like the Army-Source deal, than just buying ad pages. "Clients want more than just an ad page in a magazine," White says. "This is our first foray into doing cool marketing programs with the Army, and it's our hope that it leads to a bigger relationship." (Calls to the Source's editorial staff were not returned.)

The Nappy Roots, one of this year's most popular hip-hop groups who traveled to the Middle East this summer on the USO tour, don't see a problem with the use of hip-hop in the Army's campaigns. "I think a lot of poor folks go into the service because that's the only way out for a better education, better jobs, and seeing the world," says the Nappy Roots' Big V. "It's their only way to travel. Everybody can't be a musician or a successful doctor or lawyer."

Some young people in the Army's target demographic agree: "The Army gives young people opportunities, especially urban people," says Sterling Canter, 23, of Brooklyn. "It's not all about killing. There's an upside to it."

"Joining the Army is a personal choice," agrees Devon Edmeade, 25, also of Brooklyn. "Even if Jay-Z was passing out enlistment papers, I'm not joining. But still -- it's a choice. They use hip-hop to market beer and clothes. So why not the Army? I think it's cool."

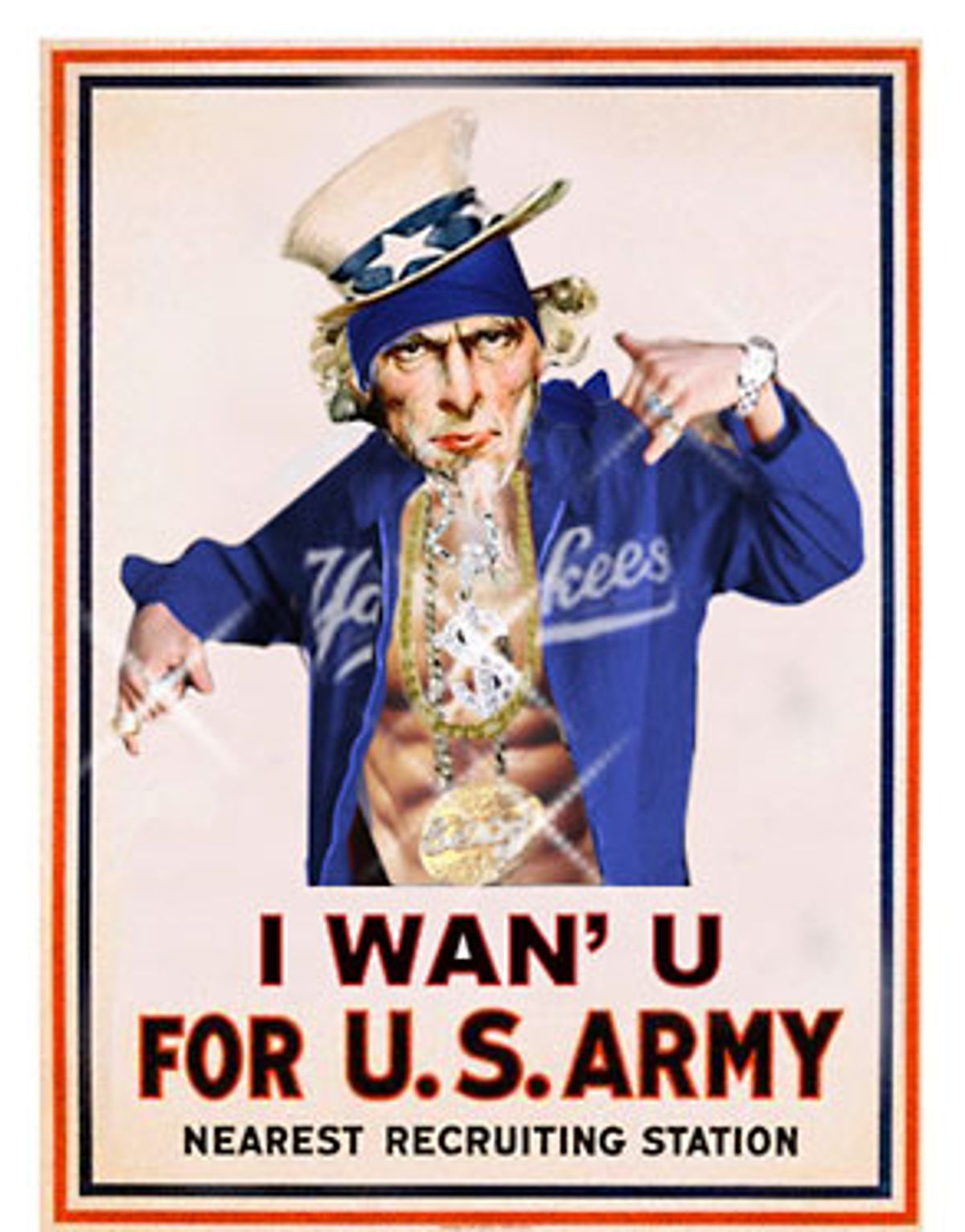

But isn't it a paradox that hip-hop -- now a culture, but one based on a genre of music rooted in inner-city resistance to the white majority -- is being used to sell the military to African-Americans? Well, sort of, say critics like Werner and Bakari. In many ways hip-hop's past has little to do with its present. The last decade has seen hip-hop evolve from gangsta rap, which reveals the hard-knock life of the projects, to a celebratory bling-blingism that fetishizes personal acquisition and the lifestyles of the rich and famous. From Biggie Smalls' yacht cruise in 1997's "Hypnotize" (arguably the watershed moment for the so-called bling-bling era) to Busta Rhymes' shill for his favorite liqueur in 2003's "Pass the Courvoisier," it's a bit hard to argue that hip-hop shouldn't be used for marketing purposes, or to draw the line between acceptable or unacceptable uses of hip-hop.

"What has hip-hop been used for? To market mainstream capitalist culture," says Werner. "The contradiction is that mainstream capitalist culture is what's keeping those kids who need the military as an escape poor. The capitalist system wants to create a desperate labor market. It wants to create a situation in which a whole lot of people with real talent are so damn desperate just to make a living that they're not going to think about the terms on which they're offered that living. You're signing up to perpetuate the same system that put you in the position where you had no alternative except to sign up."

Franz Mullings, 20, a student at the New York City Technical College, agrees. "I don't think they should exploit hip-hop to get people to join the Army," he says. "Hip-hop's not what the government is about. They don't care about people in the hood. They don't come around when things are going down. They shouldn't exploit our culture."

It's not the Army's place to address or solve these issues, says Muse Cordero Chen's Martin. "I know very few marketing campaigns that have been able to vault over and satisfy solutions for specific larger social problems," he says. "Our goal is to present the Army as an option for career advancement, as a life alternative, and as a way to represent one solution out of many for African-Americans specifically. If someone's looking for a way out of their current position, the Army presents a very compelling argument."

For Rangel, it's not just the message -- it's the medium. "It's so unfair to people who don't have an even playing field in this country to give them the option to run around in Hummers and play hip-hop games," he says, "when, at the end of the day, what you're talking about is putting their life on the line."

Shares