When you talk to Stephen Glass about Stephen Glass -- the villain in the new movie "Shattered Glass," the misunderstood antihero of his novel "The Fabulist" and the guy sitting right in front of you -- it's easy to get a little confused about whom, actually, you're talking about. He gets a little confused too, insisting that his novel is not a memoir and cannot be treated as fact at one moment, then defending the factual representations in the novel the next.

For the uninitiated, though, this much remains clear: Glass perpetrated one of the great journalistic frauds in modern American history. In 1998 -- before Jayson Blair was out of college -- Glass, a 25-year-old rising star at the New Republic, was caught making up one of his stories. An internal investigation by the magazine followed, and the number of discredited stories ballooned to 27, and that doesn't include major pieces he penned for Rolling Stone, George and Harper's, whose editors were also duped by Glass' wonderfully lurid tales of drug-abusing young Republican activists and Wall Street traders who worshipped at a shrine dedicated to Alan Greenspan. [Full disclosure: I assigned Glass a feature that year, before the scandal broke, while I was an editor at another magazine. He never turned it in.]

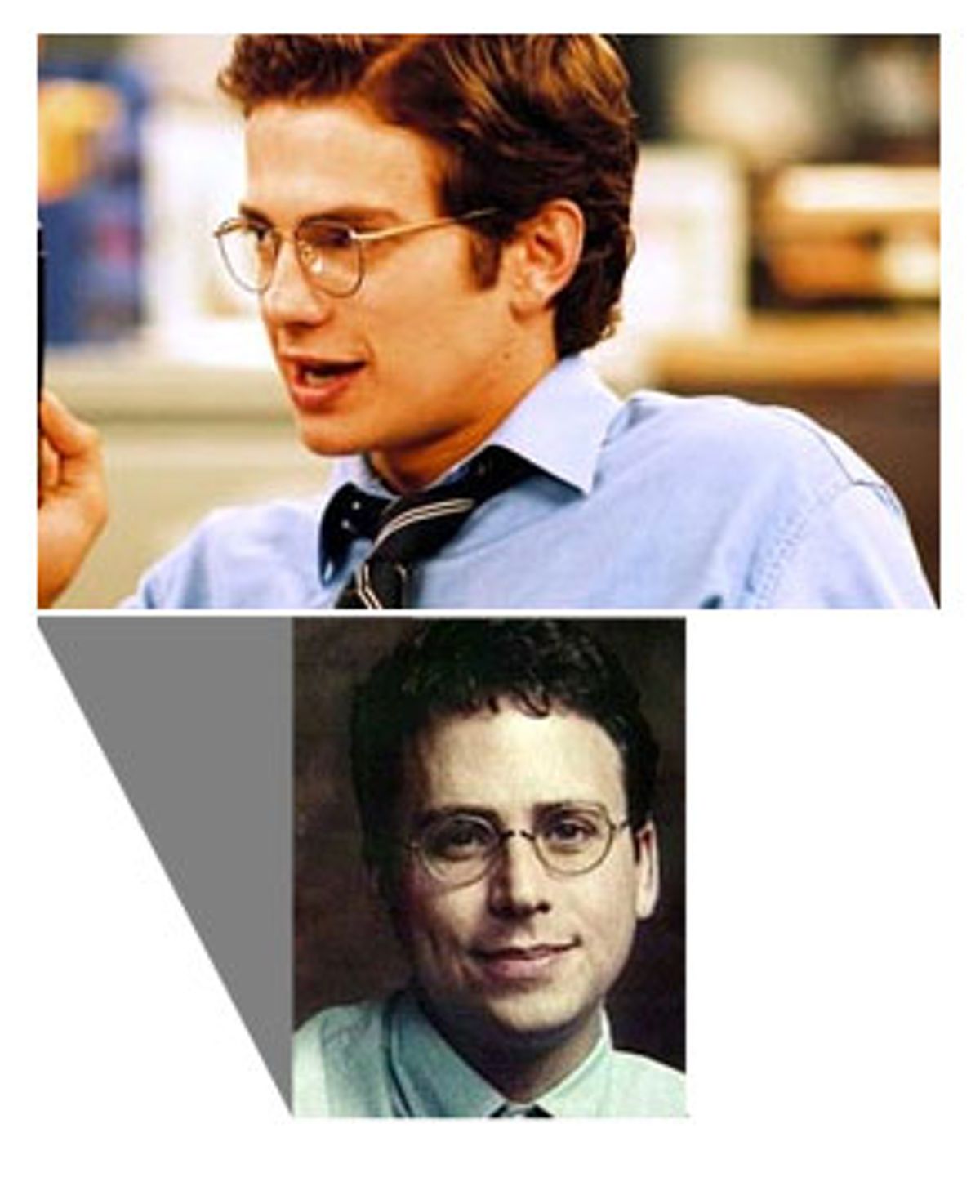

Almost as fascinating as his fantastical stories were Glass' elaborate efforts to cover his tracks. Before reporter Adam Penenberg, of Forbes.com, exposed his lies, Glass fabricated e-mails, Web sites and voice mails in order to evade fact-checking staffs. The skittish boy-man who attracted editors now drew reporters eager to expose the whole, sordid story. And on Friday, "Shattered Glass," which features "Star Wars" star Hayden Christensen as Glass and is based on a story that appeared in Vanity Fair, will make Glass an even bigger name -- and object of scorn -- outside of media circles. Christensen plays Glass as an obsequious shape-shifter, eager to please and preemptively apologetic -- his main tic is to plaintively ask, "Are you mad at me?" the moment anyone signals disappointment. The movie opens on Halloween, which will seem appropriate to many; after this, Glass will be enshrined as journalists' favorite monster, our own smirking Chucky doll.

Glass says he's trying to make amends for his misdeeds and move on. He is at work on his next novel, and hopeful of soon passing the New York Bar. (He says he passed the written exam three years ago, shortly after graduating Georgetown Law School, but his case has been under review since by the New York Bar's committee on character and fitness.) But the biggest mystery left unsolved by the movie -- and the novel, and the countless magazine stories written about the scandal -- is the most basic one: Why did he do it? Last week Salon interviewed Glass, by phone and in person.

So, you've been to a screening of "Shattered Glass," and you like it?

Did I like the movie? I couldn't watch much of the movie. It was my own personal horror film. It was seeing the moments of my life I am most ashamed of and having them portrayed by excellent actors. But in total fairness, the movie has strong performances.

When did you first have to look away?

There were whole chunks of the movie I had to look away. It's very, very painful to watch the things you hate most about your life, and what you did, and see it up on a movie screen.

Anything about the film you think was unfair, or inaccurate?

They got very many things right about the story, I want to be clear on that. In particular Chloë Sevigny's performance -- I don't know [then-Forbes' reporter] Adam Penenberg, so I don't know how Steve Zahn [did] -- but what emotionally they got right with Chloë Sevigny was a sort of moral pole that could have easily been lost or forgotten --

Sevigny is presumably portraying a character based on your TNR colleague Hanna Rosin --

Yes, but I also think she represents a whole important moral pole that's beyond her, I mean inclusive of her, but what it means to be someone's friend and what it means to be loyal and how devastating that can be, and how loyalty can be tested. That's something I truly am ashamed of, and something [they] did a really wonderful job presenting.

Because I wasn't involved in the movie and wasn't a part of the movie, I don't feel it represents what it feels like to go through this. But there are limitations to what you can do. At the same time, they took an incredibly interior story, a nonfilmic story, a story that's not just about writing but about someone, me, who invents [his] stories ... and they rendered that on the screen, and that's an amazing accomplishment.

There are key differences, though, between the film and your book, "The Fabulist." The most notable one being the way Charles Lane, TNR editor at the time you were caught, is portrayed. In the movie, he's the unquestionable hero. In your novel, the character seemingly based on Lane, Robert, is not a hero, or a sympathetic character at all.

I want to say that my book was squarely a novel. And while it was inspired by real events, I was trying to tell an emotional story and so I wasn't presented with the same challenges as the movie.

I do think Chuck is presented as a hero in the movie and I do think he did do something very, very noble, and is right to be celebrated. He did the right thing when it might have been a difficult thing to do. He behaved, at a very tough time, very well. At the same time, I behaved disastrously poorly.

But then why is he -- or the character he inspired -- such a bad guy in your book?

The novel is really a character study, an exploration of one individual ... The other characters [are] used to explore the central figure. And I think that's true of many novels, especially many that use some humor and are written in the first person, whereas the movie is done from an omniscient third-person perspective.

So it's unfair to think that Robert is the Chuck Lane character?

That's how I feel.

You insist on talking about "The Fabulist" as a novel, but it was inevitable that people read it as a roman à clef. Do you regret it?

That was the novel I wanted to write and felt a passion about writing. I spent a lot of my time regretting a great deal of my life. I feel different emotions other than regret about the way people interacted with the book. I feel grave regret about not apologizing sooner, and I feel enormous remorse about my past misbehavior, which is horrible. "Regret" is not the word I would use to describe how I feel about the way in which people interacted with the book.

I should say I don't read a lot of media gossip, unless someone sends it to me. And I don't read reviews unless someone asks me something about one. But I want to say that there's an important strain in American literature in which people write stories about their own terrible misdeeds. And I think that seems lost on some people.

Well, let me ask you about one review that goes to that point. Jonathan Chait, a former TNR colleague of yours, reviewed the book --

I haven't read it.

Well there was one thing in particular that he objected to --

You're saying there's one thing he objected to? Or there's many but just one you want to talk about?

Well, one I want to ask about. He wrote that he felt the character that resembled him, Brian, called the novel's "Steve Glass" to reject any apology for the series of lies and fabrications before Glass had a chance to offer one. He claims that never happened. ["Glass explicitly presents this as justification for not having apologized or explained his behavior to his friends," Chait wrote. "But, in fact, I never wrote or spoke to him after discovering his fabrications; nor, to my knowledge, did any other writers at TNR."] And he suggests that you still see yourself as the victim in all this, that you imagine yourself "more sinned against than sinning."

I want to be really clear about this: I don't feel comfortable criticizing my reviewers.

This is a little different. It's a former colleague --

Yeah, I'm just not comfortable criticizing reviewers. I'm sorry if his experience of his reading of the book caused him additional pain, or it mischaracterized how he was in some way a victim in all of this. Again, it's a novel, and I've caused Jon enormous pain, and I'm sure trouble -- I haven't spoken with him -- but I can only imagine I've hurt him in significant ways. And I feel terrible about that.

But this goes back to my central point here, which is that I don't have the feeling to make me want to criticize my reviewers. That's not how I feel.

OK, but do you regret that you didn't, in some way, do something to make it less inevitable that everyone who picked up the book would read it as memoir?

Had I apologized sooner, then the people I hurt would not have had their first experience with me be this book. That's one of my many regrets. I should have apologized sooner, much sooner.

Has anyone accepted the apology?

Some have. Others I haven't heard from. Some I think probably don't accept my apology. This is still the early stages of a long, long process of apologies. It may never [be accepted], or more likely it will take time.

I met you briefly a few times before the whole controversy in 1998, and noticed in the film how Hayden Christensen captured some of your mannerisms. Did you meet with him?

He never sought me out, and I've never spoken to him. Well, it's possible he wrote some letter or something. I haven't always been the easiest person to seek out.

But yeah, there are some mannerisms that were creepy to see. The detail, and it's a minor, almost irrelevant detail, but the moment in the office when he didn't have his shoes on? I tend to take my shoes off in offices. It was a moment I was taken aback by.

There was another scene I wanted to ask you about. Glass -- well, you -- is telling one of his colleagues about how you went out with some male Washington Post reporter, and was shocked when he kissed you; or, more precisely, when he stuck his tongue down your throat. Why do you think they put that scene in the movie?

I don't know why they put that in the movie.

Was it based on reality?

There was an incident earlier in my career in which a gay reporter from another publication seemed to be interested in me. So I assume that's what it was.

The impression it gave -- an impression I know others shared about you at the time -- was that you were a sort of cipher. People don't know who -- or what -- you were. A fair characterization?

I think I didn't have a great understanding of who I was, otherwise I would have been more honest with myself, and therefore wouldn't have been lying. So to the extent I was a cipher to myself, I was a cipher to others as well.

You suggest as much in the book, though, too. There are a few similarly jarring moments. I'm thinking about the time you -- or, rather, the Steve in the novel -- puts on copious amounts of women's makeup to get in the character of a woman he was making up for one of his stories. Another time, Steve is stuck wearing his girlfriend's underwear because he doesn't have any of his own. Any freshman lit student would highlight these passages and write "identity confusion," or "gender confusion," in the margins.

I think what the book is trying to communicate is that the narrator is trying to become a fictional character, a character he's not. And I don't mean it in just a literal meaning; he's going through a troubled period in his life where he is trying to figure out who he is.

Andrew Sullivan once told me that during your job interview for TNR, he asked you what, aside from politics, you were interested in, and you blurted out, "Show tunes!" He says he wondered later if it was true, or just a way to try to insinuate yourself with a gay man -- though he's quick to point out he doesn't like show tunes.

I know virtually nothing about music. I don't really own CDs. My father loved show tunes, and I was involved in musicals in high school. I was not playing to the choir. It's about the only music that I know anything about.

So it's true, then. But what sort of show tunes?

I used to run at the gym to show tunes. What I liked about them is that there was a long narrative you could follow. I have run in the past to "Les Miz."

Do you still think of yourself as a cipher?

I've had a great deal of therapy. I feel I understand myself -- and as part of that, understand the pain I've caused others -- a great deal more.

But do you understand why you did what you did? The real weakness in the movie -- and reviewers have pointed out, in your book as well -- is that ultimately it doesn't explain why you did it?

I think that's absent in the movie.

But it is in the book, too, right? "The Fabulist" sort of suggests that Steve is under enormous pressure, presumably social but also from his family. Then later, we meet Steve's family, and they seem genuinely supportive and warm.

I think an important point there, and maybe it's a point that wasn't clear, is that ... other people have asked me this, "Did your parents make you do this." And the answer is no. I think my parents have done nothing wrong here, and were proud of me. Parental pressure did not lead me to do what I did. That doesn't mean I haven't accused them, wrongly, at times.

Do you think you do so in the book?

Accuse my parents? Well, I think the narrator, and let me be clear it's not me, I don't think he accuses his parents. I think he has a warm relationship with his parents, and he doesn't always understand them.

So when you say you have accused them, do you mean you, or the Steve in the book?

I'm saying in real life. I've accused my parents in real life.

Publicly?

No, I mean among friends. I'm sure I've wrongly said, "My parents have pushed me into law school." But that's not true.

So it wasn't the parents. Then what was it?

I get asked this a lot. A deep, deep feeling of unhappiness of who I was, and a deep belief that I was not good enough, and I mean that in the broadest sense. Not good enough as a person, not good enough as a friend, not good enough as a writer, not good enough as a journalist, not good enough in any way. And a horrible confusion that if people around me thought differently about me than me, then maybe I would, too. And so I manipulated those views in a number of ways. One of the ways was lying about my life. Another connected way was lying in my stories. And those two things go hand in hand.

Where did that come from, though? I mean, look, on the surface, you'd lived a pretty charmed life, a pretty good life.

I think those causes are very personal. But I think those causes come from a feeling of not connecting with the world in many ways. That I'm somehow different and bad. And so I felt that way all throughout my life. Now lying was not something I did all throughout my life to address those things, but there were other behaviors -- I was in 8 zillion different extracurricular things in high school. That's another way.

You talk a lot about having gone through a lot of therapy. So, what is the diagnosis? When compulsive liars are covered by the media, they're invariably described as sociopaths.

I don't even know what the term truly means. What I do know for me is that I was not a sociopath or a psychopath. I feel that even in denying that ... [Trails off] I guess that what I feel is an enormous amount of self-loathing, and a self-destructive nature, as well as an outwardly destructive nature.

So you're not a sociopath -- got it.

See, I regret even saying that now, because I can only see the headline. "Glass: Not Sociopath." I hope you won't present it in that way.

Well, let's move on to someone facing that sort scrutiny, Jayson Blair.

I don't follow these things. I don't read, like, Romenesko or anything. I just can't.

But you followed the story?

I know the story, sure.

Did you feel sympathy for him?

My reaction, and this is my reaction to all types of things in the past few years, is that I see them as human tragedies. I'm less interested in them as journalism stories. I read about people all the time who do things that I'm sure they regret, [I have] much greater human feelings for them. I understand what sort of toll this takes on them and their lives. My gut feeling was, this is going to be a terrible time for him. I hope he finds some peace through it.

You, meanwhile, have made a return to journalism writing about marijuana laws in Canada for Rolling Stone.

I wrote a piece for Rolling Stone. They published a piece of mine.

What was it like returning to journalism?

I just don't feel comfortable talking about that, except to say one thing, which is that I've been unbelievably appreciative to Jann Wenner and everyone at Rolling Stone, which has been kind and generous. Other than that, I don't have anything to say.

Are you going to do more?

I just don't want to talk about the whole journalism thing.

Shares