In Baghdad, the Bush administration acts as though it is astonished by the postwar carnage. Its feigned shock is a consequence of Washington's intelligence wars. In fact, not only was it warned of the coming struggle and its nature -- ignoring a $5 million State Department report on "The Future of Iraq" -- but Bush himself signed another document in which that predictive information is contained.

According to the congressional resolution authorizing the use of military force in Iraq, the administration is required to submit to Congress reports of postwar planning every 60 days. One such report -- previously undisclosed but revealed here -- bears Bush's signature and is dated April 14. It declares: "We are especially concerned that the remnants of the Saddam Hussein regime will continue to use Iraqi civilian populations as a shield for its regular and irregular combat forces or may attack the Iraqi population in an effort to undermine Coalition goals." Moreover, the report goes on: "Coalition planners have prepared for these contingencies, and have designed the military campaign to minimize civilian casualties and damage to civilian infrastructure."

Yet on Aug. 25, as the violence in postwar Iraq flared, Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld claimed that this possibility was not foreseen: "Now was -- did we -- was it possible to anticipate that the battles would take place south of Baghdad and that then there would be a collapse up north, and there would be very little killing and capturing of those folks, because they blended into the countryside and they're still fighting their war?"

"We read their reports," a Senate source told me. "Too bad they don't read their own reports."

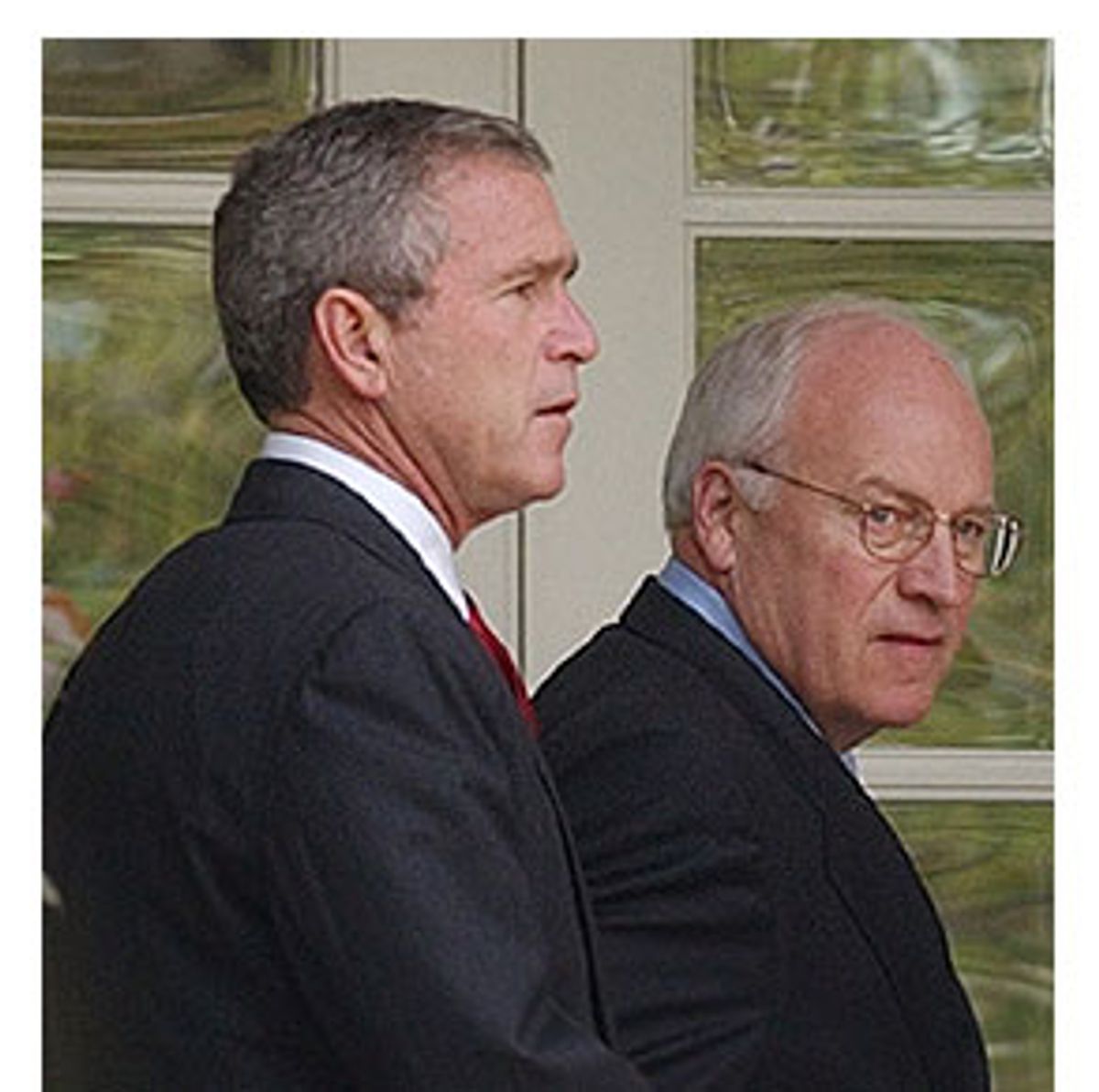

In advance of the war, Bush (to be precise, Cheney, the de facto prime minister to the distant monarch) viewed the CIA, the State Department and other intelligence agencies not simply as uncooperative, but even disloyal, as their analysts continued to sift through information to determine what exactly might be true. For the intelligence analysts, this process is at the essence of their professionalism and mission. Yet the strict insistence on the empirical was a threat to the ideological, facts an imminent danger to the doctrine. So those facts had to be suppressed, and those creating contrary evidence had to be marginalized, intimidated or have their reputations tarnished.

Twice Vice President Dick Cheney veered his motorcade to the George H.W. Bush Center for Intelligence in Langley, Va., where he personally tried to coerce CIA desk-level analysts to fit their work to specification in the run-up to the war.

If the CIA would not serve, it would be trampled. At the Pentagon, Rumsfeld formed the Office of Special Plans, a parallel counter-CIA under the direction of the neoconservative Deputy Secretary of Defense Paul Wolfowitz, to "stovepipe" its own version of intelligence directly to the White House. Its reports were not to be mingled or shared with the CIA or State Department intelligence for fear of corruption by skepticism. Instead, the Pentagon's handpicked future leader of Iraq, Ahmed Chalabi of the Iraqi National Congress, replaced the CIA as the reliable source of information, little of which turned out to be true -- though his deceit was consistent with his record. Chalabi was regarded at the CIA as a mountebank after he had lured the agency to support his "invasion" of Iraq in 1995, a tragicomic episode, but one that hardly discouraged his neoconservative sponsors.

Early last year, before Hans Blix, chief of the United Nations' team to monitor Iraq's weapons of mass destruction, embarked on his mission, Wolfowitz ordered a report from the CIA to show that Blix had been soft on Iraq in the past and thus to undermine him before he even began his work. When the CIA reached an opposite conclusion, Wolfowitz was described by a former State Department official in the Washington Post as having "hit the ceiling." Then, according to former Assistant Secretary of State James Rubin, when Blix met with Cheney at the White House, the vice president told him what would happen if his efforts on WMD did not support Bush policy: "We will not hesitate to discredit you." Blix's brush with Cheney was no different than the administration's treatment of the CIA.

Having already decided upon its course in Iraq, the Bush administration demanded the fabrication of evidence to fit into an imminent threat. Then, fulfilling the driven logic of the Bush Doctrine, preemptive action could be taken. Policy a priori dictated intelligence à la carte.

In Bush's Washington, politics is the extension of war by other means. Rather than seeking to reform any abuse of intelligence, the Bush administration, through the Republican-dominated Senate Intelligence Committee, is producing a report that will accuse the CIA of giving faulty information. While the CIA is being cast as a scapegoat, FBI agents are meanwhile interviewing senior officials about a potential criminal conspiracy behind the public identification of a covert CIA operative -- who, not coincidentally, happens to be the wife of the former U.S. ambassador Joseph Wilson IV, author of the report on the false Niger yellowcake uranium claims (originating in the office of Vice President Dick Cheney). Wilson's irrefutable documentation was carefully shelved at the time in order to put 16 false words about Saddam Hussein's nuclear threat in the mouth of George W. Bush in his State of the Union address.

When it comes to responsibility for the degradation of intelligence in developing rationales for the war, Bush is energetically trying not to get to the bottom of anything. While he has asserted the White House is cooperating with the investigation into the felony of outing Mrs. Wilson, his spokesman has assiduously drawn a fine line between the legal and the political. After all, though Karl Rove -- the president's political strategist and senior advisor, indispensable to his reelection campaign -- unquestionably called a journalist to prod him that Mrs. Wilson was "fair game," his summoning of the furies upon her apparently occurred after her name was already put into the public arena by two other unnamed "senior administration officials."

Rove is not considered to have committed a firing offense so long as he has merely behaved unethically. What Bush is not doing -- not demanding that his staff sign affidavits swearing their innocence, or asking his vice president point-blank what he knows -- is glaringly obvious. Damaging national security must be secondary to political necessity.

"It's important to recognize," Joseph Wilson remarked to me, "that the person who decided to make a political point or that his political agenda was more important than a national security asset is still there in place. I'm appalled at the apparent nonchalance shown by the president."

Now, postwar, the intelligence wars, if anything, have gotten more intense. Blame-shifting by the administration is the order of the day. The Republican Senate Intelligence Committee report will point the finger at the CIA, but circumspectly not review how Bush used intelligence. The Democrats, in the Senate minority, forced to act like a fringe group, held unofficial hearings this week with prominent former CIA agents: rock-ribbed Republicans who all voted for and even contributed money to Bush, but expressed their amazed anger at the assault being waged on the permanent national security apparatus by the Republican president whose father's name adorns the building where they worked. One of them compressed his disillusionment into the single most resonant word an intelligence agent can muster: "betrayal."

Shares