Readers who picked up their New York Times on Thursday morning were treated to a bombshell -- a front-page article detailing a bizarre, murky escapade in the weeks leading up to the war, when increasingly desperate Iraqi officials used a mysterious Beirut middleman to offer the U.S. just about any deal it wanted to avoid invasion. A key U.S. hawk with close ties to the Bush administration met with the middleman and told the CIA he was willing to explore it further, but the agency aborted his mission. For their part, Pentagon officials denied that they knew about the offer -- oddly, since the middleman's U.S. contact worked for the Pentagon. In any event, the feeler was ignored and the invasion proceeded as planned.

The story, as told in the Times and in three other news reports that preceded it, is at once a film noir, a comic strip and a tragedy. It's one of the most peculiar, incompletely reported, ambiguous and at times contradictory tales to hit print in recent memory. And its central characters -- Richard "Prince of Darkness" Perle, the fabled neocon guru and offstage string-puller; middleman Imad Hage, a Lebanese-American businessman under investigation for gun-running; Michael Maloof, a Pentagon official working for superhawk Douglas Feith's secret intelligence unit who lost his security clearance under controversial circumstances; and an Iraqi intelligence honcho who collapsed minutes after walking into Hage's office -- are some of the strangest since Sidney Greenstreet and Peter Lorre inspired unease on the big screen.

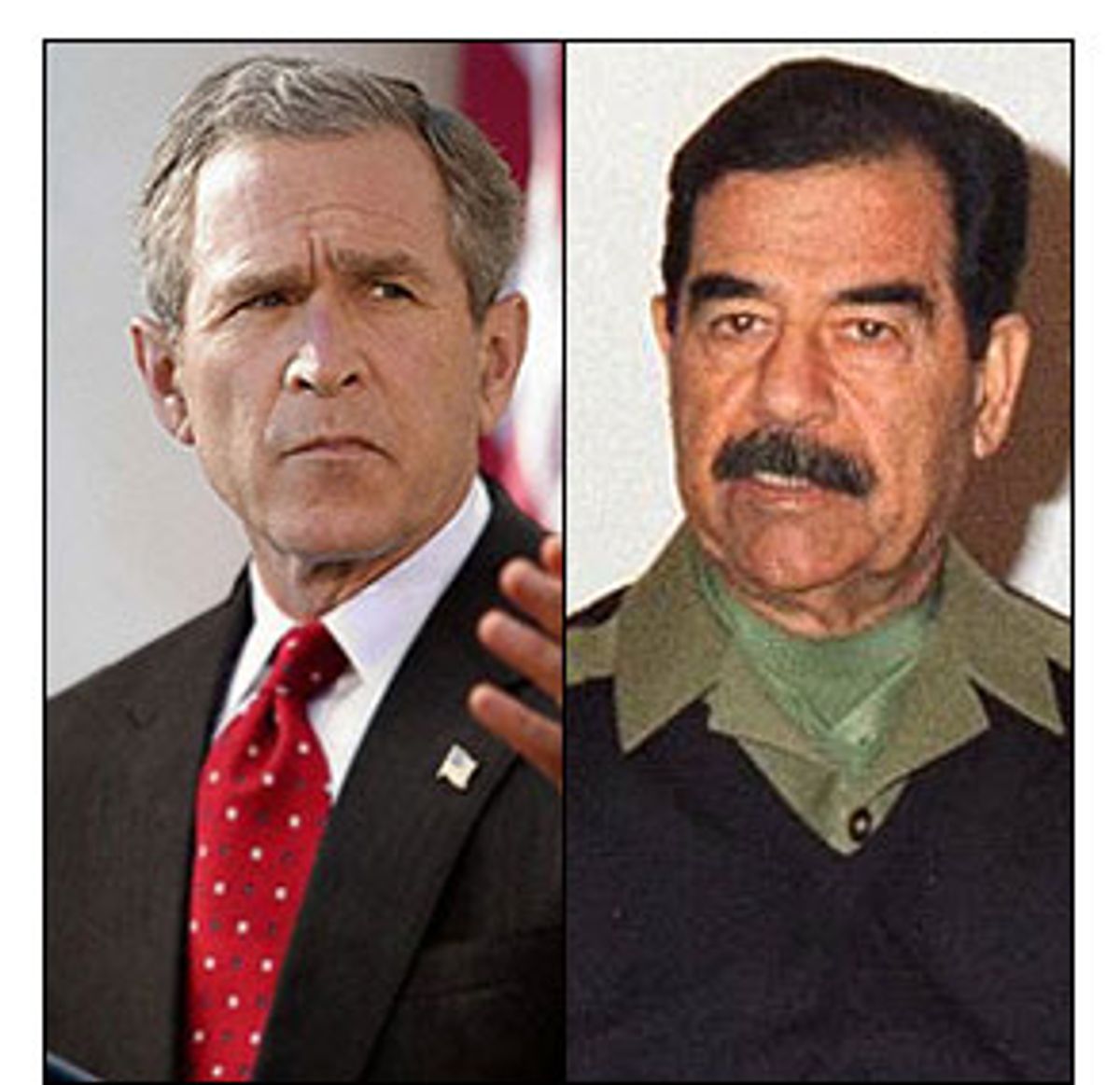

At face value, the Case of Saddam's Desperate Last-Minute Offer paints a damning picture of the Bush administration as so eager to go to war that it failed to pursue an admittedly strange but promising back channel. That's how Thomas Powers, author of "Intelligence Wars: American Secret History From Hitler to Al Qaeda," sees it.

"It's reasonable to believe that the Iraqis were trying to do anything they could to avoid an invasion; they did that before the Gulf War in 1991 -- last-minute attempts to stave it off was one of Saddam Hussein's specialties, driving people crazy by leading them right up to the brink," Powers says. "But what he was offering wasn't good enough for the administration. The administration would accept no less than having Saddam removed from power, and that the United States would occupy the country and be in charge of setting up a replacement government. That was the minimum demand from the beginning.

"I think it serves as an indicator of just how uninterested the administration was in any solution that didn't involve the occupation of Iraq by the United States."

U.S. officials have taken a boilerplate line that the offer was not credible, that legitimate channels were available to the Iraqis, and that the Bush administration explored every possible avenue to avoid war. Asked today if President Bush knew about the back-channel offer, White House spokesman Scott McClellan did not answer, but said, "We exhausted every legitimate and credible opportunity to avert military action and to achieve a peaceful solution to this." Larry DiRita, chief of Pentagon public affairs, told Newsweek, "Iraq and Saddam had ample opportunity through highly credible sources over a period of several years to take serious action to avoid war and had the means to use highly credible channels to do that. Nobody needed to use questionable channels to convey messages."

Lurking behind this official line is another one, which can only be understood in the context of the full-blown war now raging between the White House and the CIA -- a conflict that began with CIA outrage at the White House's demand for cooked intelligence, boiled over with the exposure of diplomat Joseph Wilson's wife, Valerie Plame, as an undercover agent in a column by White House crony Robert Novak, and has been steaming ever since in a campaign of leaks and counterleaks. This line is yes, the administration explored every genuine offer, but if we missed this one it was the CIA's fault. Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld said Thursday that he had no direct knowledge of the offer but "clearly, the CIA considered it and dealt with it in a way that they felt was appropriate." The Pentagon denies that it knew about the Hage offer, but after delving into the Byzantine byways of this story, not everyone will find that position credible.

At least partial confirmation of Powers' suspicions was offered by a U.S. official quoted by Knight-Ridder, which along with ABC and Newsweek ran pieces Wednesday night. Knight-Ridder quoted "a senior administration official" who, referring to the Hage offer and others, said, "They were all nonstarters because they all involved Saddam staying in power."

For its part, the Washington Post decided the case of the last-minute peace offer was a complete nonstory, running a perfunctory six-paragraph piece that quoted U.S. officials dismissing it out of hand. It's hard to escape the feeling that the Post's brief, dismissive story is a malevolent pin, intended to prick what they regarded as a big hot-air balloon inflated by the credulous Times.

Is this a nonstory? If U.S. officials are right and the offer was bogus, clearly. But at this point there's not enough evidence to dismiss the offer as just another Saddam ploy: The official statements have been general and anodyne. Which leaves the other, trickier reason to believe it's a nonstory: that there are so many hidden agendas at work that it's impossible to take any of it seriously.

Certainly there is no shortage of candidates who could have hidden agendas. Michael Maloof and his hawkish friends at the Pentagon could have put out the story in an attempt to rehabilitate Maloof and smear the hated CIA, as blogger Joshua Micah Marshall speculated. Or it could be some kind of dark, ominous Richard Perle smokescreen laid down for unknown reasons, as a source with longtime knowledge of Perle and the intelligence community told Salon. And then there's the middleman, Hage -- the leading source for the Times article, but a figure much more intriguing and ambiguous than the curiously incomplete Times portrait would lead one to think. The Times notes merely that Hage was briefly detained at Washington's Dulles Airport when a gun was found in his checked luggage. But according to a Knight-Ridder story dated Aug. 1, 2003, Hage "is under federal investigation for possible involvement in a gun-running scheme to Liberia, the West African nation embroiled in civil war." Could Hage -- who is also an aspiring Lebanese politician, another fact not mentioned in the Times story -- have inflated the import of his conversations with Iraqi officials to try to clear his name?

Of these theories, the least plausible on the face of it would seem to be that Perle is behind the story. It's true that the conniving neocon initially comes off looking good, albeit in a most unexpected way (perhaps the founder of the Bring Me the Head of Saddam Hussein University just wanted to have a good laugh by portraying himself as a dedicated seeker after peace), and the CIA comes off looking like the bad guys -- which neatly fits the Bush hawks' script these days. But in fact the larger import of the story runs completely against everything that Perle believes in. Telling the American public, at a moment when the Iraq occupation is becoming a blood-soaked, slow-motion nightmare, that the U.S. turned down a possibly credible peace offer does not advance his hard-line agenda. As for smearing the CIA, that won't work either, because in the end it's not credible that only the CIA knew. A source close to the intelligence community derided the idea that Perle, who detests the CIA, would have gone to the spy agency rather than to his friends in the Pentagon, where he serves on Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld's advisory board, if he really wanted results.

The New York Times report, which was written by Jim Risen, doesn't go into this. That's not the only nagging question left hanging by Risen's account. According to the Times, Maloof passed along the Iraqi offer to Deputy Defense Secretary Paul Wolfowitz's top aide Jaymie Durnan, but inexplicably Durnan "never discussed the Hage channel to the Iraqis with Mr. Wolfowitz." Risen left unexplored why Durnan would not have discussed a matter of such potential moment with his boss.

Newsweek, however, goes deeper -- although in the end the impression it leaves of Durnan's attitudes toward Hage and his offer raise as many questions as the Times piece. The Newsweek story, by Michael Isikoff and Mark Hosenball, reports that Durnan said he never thought Hage's story was worth pursuing. Of Durnan's one meeting with Hage (which Maloof also attended) on Jan. 28, 2003, in Washington, Newsweek says that Durnan "didn't recall El-Hage pushing any particular peace plan. 'I just listened to him,' Durnan said. 'It was a non-event.'" But Newsweek also reports (as did the Times) that Durnan subsequently asked in e-mails for background information about Hage.

The Times piece leaves the impression that Durnan was checking because he was trying to assess the credibility of the possible peace offer. But Newsweek quotes Durnan as saying, "I wasn't concerned about the issues. I was concerned that [El-Hage] had my name and phone number and that I could become a target of some a-hole from the Middle East." When Hage was detained, U.S. officials found Durnan's card in his possession. Durnan told Newsweek that Maloof, not he, had given Hage his card. "'I was pissed,' Durnan said."

That Maloof (perhaps with Perle's tacit blessing) or even Hage could have an interest in spinning this story seems at this point more plausible. Maloof in particular has a most enigmatic story. Maloof worked in a two-man Pentagon intelligence unit that was created by fellow hawk Feith to find connections between Iraq and al-Qaida, connections the Bush administration desperately wanted to produce to justify going to war. Maloof lost his security clearance for reasons that are in dispute. The Times notes in parentheses: "In May, Mr. Maloof, who has lost his security clearance, was placed on paid administrative leave by the Pentagon, for reasons unrelated to the contacts with Mr. Hage."

Other news outlets go deeper, however. Newsweek reported that Maloof and his allies believe his security clearance was not restored (it was originally revoked because he allegedly failed to "properly report his marriage to a citizen of a former Soviet republic") because he "questioned official analyses that played down alleged state sponsorship of al-Qaida." They also assert that his role in putting Hage together with Durnan angered his enemies, who saw it as evidence that he and other hawks were a rogue outfit. (The two-man team he and fellow hawk David Wurmser manned was the precursor of the now-notorious Office of Special Plans, set up by Rumsfeld to bypass normal intelligence channels and provide the administration with the evidence they wanted to justify war with Iraq.)

"It's clear Maloof is in some kind of trouble, though we don't know what kind," Powers said. A source with close ties to the intelligence community speculates that Maloof may have lost his clearance for leaking classified information to the press.

It's impossible to untangle these threads, without the full power of a congressional hearing (and don't hold your breath for that, with the Republicans in firm control of Capitol Hill). But the fact remains that even if the story was put out by figures with self-serving agendas, that doesn't necessarily make it untrue.

At this point we have only the word of Hage and Maloof, both problematic figures, that the Iraqi regime's peace offer was legitimate. But working through a shadowy cutout would be quite in character for a desperate Saddam Hussein. Thursday's Guardian reported that Iraqi officials also attempted to contact former CIA counterterrorism chief Vince Cannistraro about a peace deal. Cannistraro said he passed the message along to senior officials at the State Department, but heard later that the Iraqi offer had been "killed" by the Bush administration.

Which leaves the question hanging: Did Bush and company decline to pursue the increasingly urgent peace feelers coming out of Iraq simply because they were determined to go to war no matter what?

That decision might have played well last March, when the public was terrified by a drumbeat of misinformation about the urgent threat posed by Saddam Hussein's nukes and other weapons of mass destruction. And it is certain to be defended in the days ahead by supporters of the war who argue that nothing Saddam Hussein offered could be trusted. But as Americans die every day in Iraq, the public may not view it so kindly.

"The interesting question is, Why did the U.S. government reject the Hage offer so quickly? Why was it so uninterested?" says Thomas Powers. "I could be wrong, but I think the principle reason was that the administration absolutely wanted to go to war. It's hard to get a war going; the great achievement of the Bush administration was that they got the war they wanted -- and there were so many things stacked against them."

Additional reporting by Mark Follman.

Shares