November has been the deadliest for both Americans and Iraqis since President Bush declared the end of major combat operations on May 1. The headquarters for the International Committee of the Red Cross was bombed. Baghdad's deputy mayor was assassinated. Three of the city's police stations were simultaneously attacked. Two U.S. helicopters have been shot down. In the past few days, alone, gunmen in Mosul opened fire on an oil company executive's car, wounding him and killing his son, and a bomb in Basra claimed several civilian casualties.

When a missile blasted the Al Rashid Hotel in central Baghdad in late October, a distinguished guest narrowly escaped injury: U.S. Deputy Defense Secretary Paul Wolfowitz, the chief architect and a leading proponent of the Iraq War. He was shaken, and a few days later, at Georgetown University in Washington, I heard him speak about the attack. Wolfowitz downplayed his own risk and his own reaction, but certainly he experienced something that many Baghdadis now experience on a regular basis: fear. The profound fear that makes your heart pound in your chest, that freezes you in your tracks, that leaves you wondering whether you are about to die.

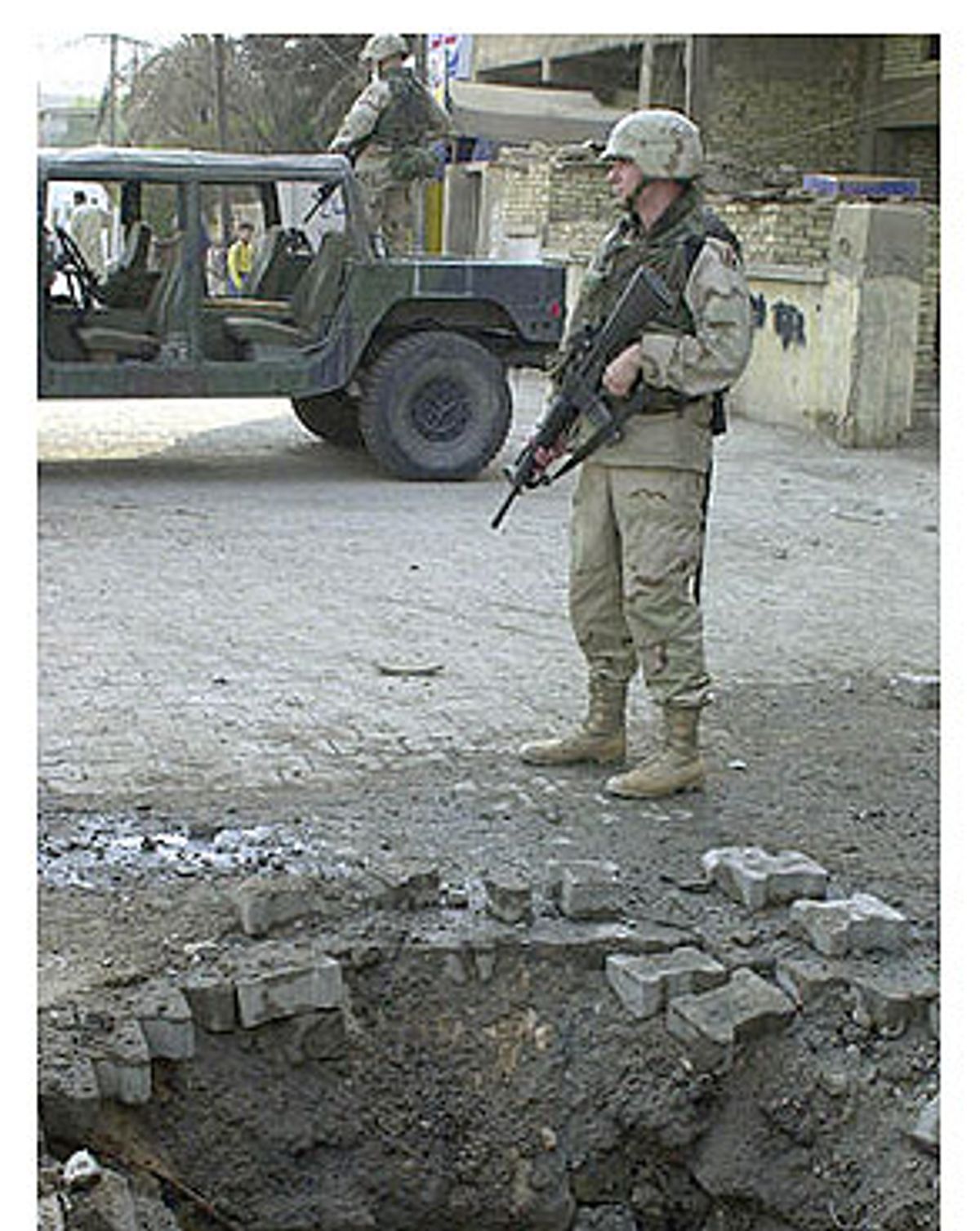

Whether the attackers are Baathists loyal to Saddam Hussein, foreign fighters, Islamic jihadis, or a nationalist resistance, a key objective of the attacks is clearly to create fear. They want to see the Americans depart, of course; but a point sometimes lost in American news coverage is that the attackers aim to intimidate ordinary Iraqis, too. Fear is also a result of the absence of law in Baghdad, the failure of the Coalition Provisional Authority to provide security against carjackings, kidnappings, armed robbery, abduction and rape, every kind of theft and general banditry imaginable. And so fear comes to the people of Baghdad in various shapes and sizes: The fears that accompany American soldiers on foot patrol in Fallujah; the fears that tear at parents' hearts sending their children to school each day, hoping they come home safely; the fears about personal security that all residents of the Iraqi capital now experience; the fears that ordinary Iraqis feel for the future of their country.

Fear is like a virus, a contagion that can come to infect whole neighborhoods, whole cities. Sometimes it starts with a single victim; I know this from personal experience. I traveled to Iraq in late August expecting to stay for two weeks of research and interviews; I'd been in Baghdad before the war, and I wanted to get a firsthand feel for the place after the fall of Saddam. But I stayed for only four days -- days in which I was constantly reminded of the danger, days in which I regularly heard gunshots and explosions, days in which every moment was colored by the possibility of spontaneous violence. And yet, in that brief time, I managed to walk Baghdad's streets more or less freely. As I rode in cabs or bought ice cream from street vendors on pleasant summer evenings, I saw a nation that was bustling with life. I had a chance to speak with ordinary Iraqis who are yearning for a return to normalcy -- and who are increasingly furious that the United States, with its mythic stores of power and wealth, has not been able to provide it.

Things have only gotten worse since my visit, and in reading the horrific accounts of recent explosions and attacks, I've come to wonder whether the United States can ever win the war if it cannot stem the fear that its often invisible opponents are injecting into daily life on the streets of Baghdad.

Before I left my home in Washington, I knew the trip would be dangerous. I read the newspapers and watched the television news shows. I've spent a lot of time in the Middle East and I have a lot of friends there, friends who have recently been to Baghdad. My friend Edmund, an Iraqi Christian, had spent several years in Iraqi prisons before managing to get out of the country. Now he works for a Jordan-based NGO doing humanitarian work in his homeland. When I spoke with him in Amman the day before my flight to Baghdad, he was blunt: "I don't advise you to go," he warned. "It's worse than the wild West. You don't know what's going to happen at any time, even before the curfew."

I was resolved to make the trip, but I was terrified that I would not return to Washington in one piece. I made it through that night and to the next morning with the help of several drinks. Once I began the routines of packing, having breakfast and making my way to the airport, things seemed almost normal, at least for the time being.

But the sense of normalcy did not last.

Our flight made a plunging descent onto the landing strip at what used to be Saddam International Airport -- a defensive measure, apparently, to counter the threat of shoulder-fired missiles. I hitched a ride into the capital with three members of the airline's ground crew, and along the way, they pointed to where the U.S. military had downed dozens of old and beautiful trees to make it more difficult for people to hide and mount attacks on U.S. soldiers. On the route to the Ard al-Zuhur Hotel (Flower Land Hotel) in the relatively well-to-do neighborhood of "outer Karada," I recognized some neighborhoods from a trip to the city last winter, before the invasion. Though I'd heard so much talk of danger, crime and violence, the streets were busy and humming with life. Businesses were open, people were out -- mostly men, of course. But then you see some bombed and burnt-out buildings and the peculiar sight of heavily armed U.S. soldiers in tanks and fighting vehicles -- clearly out of place as they patrolled an Arab city -- and you remember that you are in a war zone.

By the time I checked in to my hotel -- an apartment building that had hastily been converted into suites, with an Internet cafe on the ground floor -- I was genuinely confused. I had just heard all about Baghdad's dangers, which had confirmed everything I had seen on television and read in the press, but I had just seen the hustle and bustle of urban life. It was now early afternoon and I didn't know whether to stay in my hotel room until my return flight to Amman two weeks away or explore the city. After washing up and calming down, I decided to venture outside to acquaint myself with the surroundings near my hotel.

Baghdad is more like Los Angeles -- sprawling, endless and suburban -- than a truly urban city, and much as I walked in the late summer heat, I seemed to be getting nowhere. But it seemed normal. Things were quiet. When I visited here last winter, before the war, I'd regularly walked the streets of the city by myself or with American friends well into the early hours of the morning. I took cabs everywhere, talked with anyone, and never felt fearful of crime, chaos or random violence. Of course, Iraq under Saddam truly was a "republic of fear" but it was a profoundly different kind of fear. Iraqis were afraid of politics and the regime, one of the most brutal, bloody and ruthless regimes the world has ever seen.

I went back to my hotel and showered. Braced by my newfound courage, I went back down to the street, hailed a regular cab, and directed the driver to the Qasr Al-Muqtamarat -- the Baghdad Convention Center on the grounds of the former Republican Palace that now serves as the headquarters for the American occupation. The conference center turned out to be part of the sealed-off American complex in the center of town that includes one of Saddam's former palaces, now home to Paul Bremer, Bush's envoy to Iraq. What is amazing -- even startling -- is that the symbolism and irony of living in and ruling Iraq from Saddam's former palace seems to be lost on the American administration. It is not lost, however, on ordinary Iraqis.

At the conference center, I met U.S. aid officials and explored the center's labyrinthine halls, which turned out to be home to all kinds of activity -- meetings, press conferences and people simply hanging out -- a mixture of U.S. military, Agency for International Development and State Department officials, private contractors and consultants, journalists, and Iraqis of all stripes. Even MCI has an office there as the company was contracted to supply the CPA with mobile phone service in Iraq.

A training session was underway for the future Iraqi Facilities Protection Service. Its forces will guard government offices, ministries and other buildings in Iraq, and they will carry arms. Their deployment, it is hoped, will dampen some of the security-related fears of many Baghdadis while freeing up U.S. forces for other duties.

I walked into a lecture hall where a U.S. soldier was onstage with an Iraqi translator, demonstrating different security principles to a crowd of about 50 Iraqi young men. The session proved fascinating and after introducing myself to the U.S. officer in charge -- Staff Sgt. Heydenberk -- I was invited to stay and observe the training.

The sessions last two full days and are followed by a graduation ceremony. U.S. officers and soldiers -- all remarkably young men -- lead the sessions with the help of Iraqi translators. Heydenberk said that he designed the course himself, which covers security procedures, defense, detecting suspicious behavior, ethics and human rights, and other subjects.

It wasn't clear to me what the Iraqi recruits learned from the training, but they certainly found it amusing. I found it to be both arrogant and naive. The U.S. instructors were fond of repeating phrases like "I know there is a lot of corruption in Iraq, but we can fix it together" and "Do not be late. Always be on time." At one point during the session covering gender relations, the U.S. soldier leading the class picked an Iraqi recruit from the audience to play the part of a woman in a role-playing exercise. Onstage, in front of his colleagues, the Iraqi man was asked to pretend to cry and be in need of help.

At the end of the skit the U.S. soldier says, "It doesn't matter if the female is ugly, pretty, tall or short. You must think of her as your mother or sister." Needless to say, for the Iraqi males the exercise was painfully awkward. At another point in the session, an African-American soldier talked about "blacks," "whites" and racism. On the day I happened to be in the audience, the Iraqi trainees, bemused, interrupted the instructor and asked the translator to explain to the American soldiers that "in Iraq, we do not have these problems." Throughout the two-day course the U.S. soldiers made the Iraqi recruits repeatedly yell the word "professional"-- in English and in a loud, booming military voice -- as if somehow this would transform the recruits into well-trained, competent security guards. If the CPA believes that this type of training will help address Iraq's security dilemma, that repeatedly yelling "professional" will help hold fear at bay in Baghdad, they are delusional -- and Iraq has a very serious problem.

After the day's session, I decided to walk around the city, get a meal, and go back to my hotel. At one point I passed about 150 demonstrators holding signs in both English and Arabic protesting unemployment. The demonstrators were positioned in front of a heavily guarded facility, most likely a government ministry, with U.S. soldiers standing watch.

After observing the protest, I took a cab to Saddoun Street, one of the city's major thoroughfares, where I had a mediocre meal of kebab, salad, rice and 7 Up for 6,750 dinars, the equivalent of three dollars and some change. I spent the rest of the afternoon looking in stores and speaking with merchants. And all along the way, I couldn't help but notice the profusion of goods for sale. Because of regular electricity outages and refrigerators that are rendered useless, ice merchants did a brisk business on the street, loading big cold bricks into the trunks of waiting cars. Elsewhere, there was an incredible variety and volume of consumer goods. In contrast to the days of sanctions under Saddam, there were refrigerators, toaster ovens, satellite dishes, television sets (with a picture of Arnold Schwarzenegger prominently displayed on the box), microwaves, fans, washers and dryers, air conditioners, power generators, bicycles and even gas heaters on display in front of the stores, for those who could afford to pay.

The rest of my day and evening were uneventful: a walk to my hotel, sending and receiving e-mail at the Internet cafe, dessert at a local ice cream parlor, and then an evening beer by the hotel pool.

The next day, I got up early and went to the conference center for appointments and a second day of the U.S. military training session for the Facilities Protection Service. After eating lunch with the Iraqi recruits (we were treated to MREs -- meals ready to eat -- by the U.S. soldiers), I left the conference center to again walk on Saddoun Street, which had proved so rewarding the previous day. After just 24 hours in the country, I was growing accustomed to the security situation. I was moving around Baghdad without too much hassle and becoming comfortable there -- despite all of the talk of crime, violence and insecurity.

I had just purchased a cold drink from a street vendor and was making small talk when we heard a thunderous explosion. It sounded like several loud blasts in short succession. I didn't know whether it was an intense gunfight with heavy artillery or something else because the sound was not that of a single, continuous blast. People began rushing in the direction of where they believed the noise came from, an alley off Saddoun Street. Everyone was focused on the direction of the blast. People in nearby buildings looked out their windows and others got on their balconies to try to determine what had happened. For a moment, everything came to a stop and my heart was racing.

A few minutes later, things on the street returned to normal; the crowd began to disperse -- just another afternoon in the city. And because I had heard several smaller blasts before in Baghdad and it wasn't clear what the latest blast entailed, I -- like many others -- didn't think too much of it. After finishing my drink and more conversation with the street vendor and another customer, I made my way to a money changer I wanted to interview.

The store was guarded by a young man with an AK-47; when a customer entered, he stood to attention. After the interview, I went outside and hailed a cab. That's when I learned about the explosion I'd heard earlier: The United Nations offices had been bombed. The cab driver was hysterical. "They hit the U.N., they've hit the U.N. They must get out, they must get out." He was an older man who looked to be in his 60s, well-spoken but overly excited; he could not restrain himself.

It was immediately clear to me who he was referring to. When he said, "They must get out, they must get out," he wasn't talking about Saddam loyalists or Arab fighters who have supposedly crossed into Iraq. He was speaking of the Americans. It was the United States, he said, that was responsible for the anarchy that now characterizes Baghdad; not because the U.S. military and the CPA have failed to provide security but because their very presence is destabilizing. His perspective -- which I heard repeated a number of times by many different types of people -- stands the traditional thinking on its head. From this perspective, it was not a question of more soldiers, different types of forces (military police instead of regular army), or different countries such as India, Turkey or Pakistan contributing troops. Unless the United States leaves Iraq, he was saying, Iraq will not experience stability.

The bombers had targeted the leading international organization -- as far as I was concerned, it had nothing to do with the U.S. military occupation. These were innocent civilians who were killed and injured. And this was disturbing, too: I was planning to visit the United Nations and to meet with staffers there the next day. Only when I returned to my hotel did I learn the full extent of the death and destruction. The BBC was airing footage taken from inside the U.N. building at the time of the explosion. The scenes were horrific; bloodied bodies and hysteria. I recognized the man who had sat next to me on the flight from Amman walking out of the building dazed and badly shaken. He was one of the lucky ones.

It was on CNN that I learned that Christopher Beekman had been killed. I won't forget this -- the reporter was Rym Brahimi, a CNN veteran whom I'd met the last time I was in Baghdad. I saw her standing on the balcony of her hotel in front of the famous square where Saddam's statue fell on April 9, and when she delivered the news about Beekman, the floor fell out of my stomach. I knew him.

I had met him in December 2002. He was UNICEF's program coordinator in Iraq, and he'd briefed the small delegation of American religious leaders I had traveled with about the health and education conditions of Iraqi women and children before the war. A Canadian citizen, he'd worked for UNICEF in Kosovo and Ethiopia before coming to Iraq. What struck me about Beekman, even in that first meeting, was his commitment. His life was devoted to improving the situation of women and children in developing nations. His was not a wild dream hatched in the basement of the Pentagon about making the Middle East safe for America by bringing democracy to Arabia.

With this terrible news, the risks and the devastation were no longer abstract. This was not a violent act of terrorism that I read about in the papers or watched on television. I'd heard it myself, felt the concussion. And Christopher Beekman, someone I had met and whom I was supposed to meet again, was dead.

My immediate reaction to the delayed news of the U.N. bombing and Beekman's death was not outrage; it was fear. I was unnerved, confused, scared. I could have been there, I thought. I could have died. All of the worries that had gone through my head in Amman came rushing back to me. Later, I would be furious about the U.N. bombing, angry at both those responsible as well as the CPA and U.S. military for failing to provide sufficient security. I was indignant that the United States had shirked its responsibility under international law by failing to provide security as the occupying power. This was inexcusable, criminally negligent. But at the time I was just scared, scared for my own safety. What am I doing here, I thought? What in Baghdad could possibly be worth risking my life for? I realized I wasn't a war reporter. I was an academic and a coward and quite comfortable with my cowardice.

I decided to leave Baghdad before the situation got worse. I knew rationally that in Baghdad I was more likely to be the victim of violent crime than a terrorist attack, but I simply wanted to leave. I had had enough. And my appointments at the U.N. would certainly be canceled, and the bombing, at the very least, would disrupt my other research plans. I wasn't the only one in a hurry to leave Baghdad. The United Nations, the Red Cross and other smaller NGOs evacuated many of their personnel to Jordan immediately after the attack.

I determined to get out, and within two days, I was on a flight. Never in my wildest dreams did I imagine that I would be so happy to arrive in the clean, orderly and sleepy city of Amman. As soon as I arrived, I took a cab to the Intercontinental. After checking in, I headed straight for the pool and found myself in a different world. Thursday is the end of the work week in much of the Muslim world, and the pool was teeming with hyperactive upper-middle-class Jordanian and Palestinian children and a few foreign tourists. It was a gorgeous day and I was alive.

Baghdad is the closest thing I've ever experienced to Thomas Hobbes' "state of nature" -- his description of life, before the invention of the political state, as "nasty, brutish and short." What so many of us take for granted -- the existence of government and the provision of law and order -- simply doesn't exist in Baghdad today. Yet the state -- which always exists in the background of modern life -- is the invisible cement that allows peaceful social intercourse. Without it, criminal activity flourishes and the only check to the use of force is force itself.

If fear can be debilitating at the level of the individual -- multiplied many times over, generalized to the level of society, it can lead to social paralysis. It is corrosive of trust, the bond between individuals and the very fabric of society. That is precisely what Saddam Hussein and the Iraqi resistance wants, and more and more in recent weeks, they seem to be winning. And the United States, thus far ineffectual against the attacks, seems to be losing.

Fear inhibits the return to normalcy -- from everyday aspects of life such as going to school or work in the morning to the willingness of Iraqi businessmen to invest in the country's future. Fear is in many ways the worst enemy of America's stated goal of building a democratic society. And fear in Iraq affects the willingness of other nations and international capital to invest in Iraq as well as the willingness of NGOs and aid organizations to remain in the country.

Baghdad, of course, is not "a war of all against all." It is a city of 4.5 million people, the vast majority of whom are trying to live their lives as close to normal as possible. It is a place of traffic jams and markets, commerce, leisure and festivity -- as well as criminal activity, danger and violence. When I was in Baghdad a couple of months ago, I enjoyed ice cream every evening -- outside -- close to my hotel, along with thousands of other Baghdadis: parents and children, young and old, men and women. It was a gesture of hope, I suppose: a sign that even under duress, life can be sweet. These days I wonder how long their hope will endure. And, perhaps strangely, I find myself contemplating a return to Baghdad in December, hoping to find a city where fear has given way to peace.

Shares